Imaging Assessment of Gastroduodenal Perforations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perforated Ulcers Shaleen Sathe, MS4 Christina Lebedis, MD CASE HISTORY

Perforated Ulcers Shaleen Sathe, MS4 Christina LeBedis, MD CASE HISTORY 54-year-old male with known history of hypertension presents with 2 days of acute onset abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, with periumbilical tenderness and abdominal distention on exam, without guarding or rebound tenderness. Labs, including CBC, CMP, and lipase, were unremarkable in the emergency department. Radiograph Perforated Duodenal Ulcer Radiograph of the chest in the AP projection shows large amount of free air under diaphragm (blue arrows), suggestive of intraperitoneal hollow viscus perforation. CT Perforated Duodenal Ulcer CT of the abdomen in the axial projection (I+, O-), at the level of the inferior liver edge, shows large amount of intraperitoneal free air (blue arrows) in lung window (b), and submucosal edema in the gastric antrum and duodenal bulb (red arrows), suggestive of a diagnosis of perforated bowel, most likely in the region of the duodenum. US Perforated Gastric Ulcer US of the abdomen shows perihepatic fluid (blue arrow) and free fluid in the right paracolic gutter (not shown), concerning for intraperitoneal pathology. Radiograph Perforated Gastric Ulcer Supine radiograph of the abdomen shows multiple air- filled dilated loops of large bowel, with air lucencies on both sides of the sigmoid colon wall (green arrows), consistent with Rigler sign and perforation. CT Perforated Gastric Ulcer CT of the abdomen in the axial (a) and sagittal (b) projections (I+, O-) shows diffuse wall thickening of the gastric body and antrum (green arrows) with an ulcerating lesion along the posterior wall of the stomach (red arrows), and free air tracking adjacent to the stomach (blue arrow), concerning for gastric ulcer perforation. -

Complicated Pseudodiverticulosis of Small Intestine: a Rare Case Report

International Surgery Journal Raj MK et al. Int Surg J. 2019 Sep;6(9):3433-3437 http://www.ijsurgery.com pISSN 2349-3305 | eISSN 2349-2902 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2349-2902.isj20194096 Case Report Complicated pseudodiverticulosis of small intestine: a rare case report Kamal Raj M., V. Venkatachalam*, Manasa A. Institute of General Surgery, Madras Medical College, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Received: 08 July 2019 Revised: 16 August 2019 Accepted: 19 August 2019 *Correspondence: Dr. V. Venkatachalam, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Diverticular disease though being a common entity in large bowel is recently noted to occur more proximally as well. In the jejunum, the mucosal outpouchings, called as pseudo-diverticulae, occurs with an incidence of 0.5-1.5%. Diagnosed incidentally as majority of them remain asymptomatic. When they are symptomatic, dyspepsia and bloating, recurrent abdominal cramping, malabsorption and megaloblastic anemia occurs. On occasions it is not uncommon for patients to present with hemorrhage, infections, obstruction or perforation. Perforation, being a rare presentation occurs in less than 6% of the cases. We present a case of a 70 year old male, who presented as acute abdomen, found to have isolated jejunal diverticular perforation intraoperatively. Keywords: Jejunal diverticula, Perforation, Acute abdomen, Pseudo-diverticulae INTRODUCTION for 2 days. He also gave history of dyspepsia and bloating following food consumption. -

Postpartum Pneumoperitoneum and Peritonitis After Water Birth Brown Et Al

Gastrointestinal Radiology: Postpartum pneumoperitoneum and peritonitis after water birth Brown et al. Postpartum pneumoperitoneum and peritonitis after water birth Vanessa Brown 1, Sascha Dua 1*, Anna Athow 1, Rudi Borgstein 1, Oladapo Fafemi 1 1. Department of General Surgery, North Middlesex University Hospital Trust, London, UK * Correspondence: Miss Sascha Dua, 18 Eton Rise, Eton College Road, London, NW3 2DD, UK ( [email protected] ) Radiology Case. 2009 Apr; 3(4): 1-4 :: DOI: 10.3941/jrcr.v3i4.12 ABSTRACT Pneumoperitoneum (the presence of free gas in the peritoneal cavity) usually indicates gastrointestinal perforation with associated peritoneal contamination. We describe the unusual case of a 28-year-old female, who was 7 days postpartum and presented with features of peritonitis that were www.RadiologyCases.com www.RadiologyCases.com initially missed despite supporting radiological evidence. The causes of pneumoperitoneum are discussed. In the postpartum period the female genital tract provides an alternative route by which gas can enter the abdominal cavity and cause pneumoperitoneum. In the postpartum period it is important to remember that the clinical signs of peritonism, guarding and rebound tenderness may be diminished or subtle due to abdominal wall laxity. CASE REPORT Journalof Radiology Case Reports was performed (Fig. 1) and the patient referred to the CASE REPORT gynaecologist who requested an ultrasound of the abdomen A 28-year-old woman presented to the emergency department and pelvis to rule out retained products of conception (Fig. 2). with a two-day history of generalised abdominal pain. She had The ultrasound showed a bulky uterus with a small amount of given birth to her first child three days previously at home. -

Acute Abdomen

Acute abdomen CASE 1: 46Y♀VOMITING 新光吳火獅紀念醫院 VS 許瓅文 103.09.09 46Y♀vomiting • Chief complaint •Past Hx – Abdominal pain, vomiting and no appetite for 2 – Ectopic pregnancy s/p OP 20yrs ago days – Pregnancy: denied • Present illness •PE – Intermittent abdominal pain – Abdomen: – Abdominal distention(+) diffuse tender(+) – Vomitus: yellowish/ greenish fluid no rebound pain – No flatus bowel sound: hypoactive – Similar episode before percussion: tympanic Impression?/ Order KUB (EIA: negative) • CBD/DC/Plt Hx • Standing abdomen • Panel Ⅰ/ T-bil/ Lipase Site of tender • PT/aPTT OP? •KUB (待EIA) Anticoagulant use? • Urine EIA •NPO • D5S run 60mL/hr Adhesion ileus Order Clinical feature •2nd KUB: ileus improved •2nd KUB: fixed bowel loop • Flatus(+), abdominal • Fever(+) • Promeran 1amp iv q6h & st Severe distension pain and distension vomiting • Persisted abd.pain • On NG with decompression improved • Rebound pain(+) • D5S run 120mL/hr Try water and soft diet Fluid resuscitation • NG decompression: 量多, • 排GI床/ 待轉EC Dry mouth/ UOP No discomfort greenish AKI? Prerenal azotemia? • f/u KUB 8hrs later MBD =>what’s next? Order Ileus • Abdominal CT with/without contrast • Abd OP Hx + ileus ≒ adhesion ileus =>empiric • B/C xⅡ Tx Bowel obstruction: • Be ware of mechanical bowel obstruction!!! • Cefmetazole 1g iv q8h & st bezoar => OP => CT indication/ OP indicated • Be ware of medication ↓ bowel motility for Abd OP Hx Pt Terminal ileitis 78y♂ Abdominal pain • Chief complaint – Abdominal pain since 6 hrs ago • Present illness – 看護:一陣一陣喊肚子痛 – Vomiting once, food content CASE 2: 78Y♂ ABDOMINAL PAIN – Diarrhea for 2 times, watery, brownish/ yellowish – No fever •Past Hx – Old CVA with bed-ridden/ DM/ HTN/ CAD Hx Impression?/ Order – Abd OP Hx: nil •NPO • PE: • D5S run 60mL/hr – Chest: clear BS, IRHB • CBD/DC/Plt – Abdomen: soft, no tender point •F/S DKA? no rebound pain • VBG G6 檢查項目避免重複開立 – Ext: warm, no pitting edema • Cr, AST, lipase, T-bil •KUB •ECG Previous ECG: Af OPD drug: warfarin 3mg qd • PT/aPTT Lab data/ Image Impression?/ Order • WBC: 22000/ seg. -

![Pdf Talk [Compatibility Mode]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4561/pdf-talk-compatibility-mode-1964561.webp)

Pdf Talk [Compatibility Mode]

13/11/55 IMAGING MODALITIES Improve reading skill of abdominal imaging • PLAIN FILM • ULTRASONOGRAPHY • BARIUM EXAMINATION ผศ นพ สิทธิพงศ ศรีสัจจากุล BODY IMAGING • CT Department of Radiology, SirirajHospital, • MRI MahidolUniversity • PET @ King ChulalongkornMemorial Hospital, 25 november12 PLAIN FILM • ACUTE ABDOMINAL SERIES -CXR upright PLAIN FILM -Plain abdomen supine and upright Density in Plain Film Plain Abdomen: Upright View 3 Liver 4 2 3 1 1 = air Properitoneal 2 = fat fat line 4 Abdominal 3 = soft tissue wall 5 4 = bone Small bowel loops 5 = metallic 1 PDF created with pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com 13/11/55 Plain Abdomen: Supine View Plain Abdomen vs Plain KUB Transverse Stomach colon Descending colon Supine Plain KUB PLAIN ABDOMEN How to read plain abdomen 1 Abdominal wall and properitonealfat line 2 Distance between bowel wall and abdominal Peripheral to central approach or vice versa wall 3 Gas distribution in GI tract ( stomach, small bowel and large bowel) 4 Soft tissue density in abdomen such as solid organs, fluid-filled bowel loops PLAIN ABDOMEN 5 Bony structures 6 Detection of abnormalities -Abnormal gas -free air , bowel dilatation, pneumatosis -Abnormal mass -intraperitoneumor retroperitoneum -Organomegaly -Abnormal calcification -Foreign bodies 2 PDF created with pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com 13/11/55 ABNORMAL PLAIN FILM CXR upright moderate to marked pneumoperitoneum Plain abdomen upright triangular sign • ICU admission • Sick patient • No upright film liver diaphragm ascites -

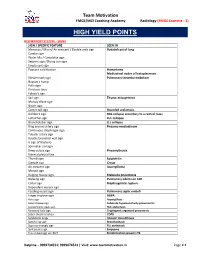

High Yield Points

Team Motivation FMGE/MCI Coaching Academy Radiology (FMGE Essentia - 3) HIGH YIELD POINTS RESPIRATORY SYSTEM – SIGNS SIGN / SPECIFIC FEATURE SEEN IN Meniscus / Moon/ Air crescent / Double arch sign Hydatid cyst of lung Cumbo sign Water lilly / Camalotte sign Serpent sign / Rising sun sign Empty cyst sign Popcorn calcification Hamartoma Mediastinal nodes of histoplasmosis Westermark sign Pulmonary thrombo-embolism Hapton’s hump Palla sign Fleishner lines Felson’s sign Sail sign Thymic enlargement Mulvay Wave sign Notch sign Comet tail sign Rounded atelectasis Golden S sign RUL collapse secondary to a central mass Luftsichel sign LUL collapse Broncholobar sign LLL collapse Ring around artery sign Pneumo-mediastinum Continuous diaphragm sign Tubular artery sign Double bronchial wall sign V sign of Naclerio Spinnaker sail sign Deep sulcus sign Pneumothorax Visceral pleural line Thumb sign Epiglottitis Steeple sign Croup Air crescent sign Aspergilloma Monod sign Bulging fissure sign Klebsiella pneumonia Batwing sign Pulmonary edema on CXR Collar sign Diaphragmatic rupture Dependant viscera sign Feeding vessel sign Pulmonary septic emboli Finger in glove sign ABPA Halo sign Aspergillosis Head cheese sign Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis Juxtaphrenic peak sign RUL atelectasis Reversed halo sign Cryptogenic organized pneumonia Saber sheath trachea COPD Sandstorm lungs Alveolar microlithiasis Signet ring sign Bronchiectasis Superior triangle sign RLL atelectasis Split pleura sign Empyema Tree in bud sign on HRCT Endobronchial spread in TB -

Perforated Duodenal Diverticulum with Subtle Pneumoretroperitoneum on Abdominal X-Ray

Hindawi Case Reports in Emergency Medicine Volume 2017, Article ID 7089573, 4 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7089573 Case Report Perforated Duodenal Diverticulum with Subtle Pneumoretroperitoneum on Abdominal X-Ray Yuzeng Shen and Mark Kwok Fai Leong Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore Correspondence should be addressed to Yuzeng Shen; [email protected] Received 18 May 2017; Revised 25 August 2017; Accepted 17 September 2017; Published 19 October 2017 Academic Editor: Kalpesh Jani Copyright © 2017 Yuzeng Shen and Mark Kwok Fai Leong. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abdominal pain is one of the most common presenting complaints at the Emergency Department (ED). Given the myriad of possible differential diagnoses for abdominal pain, it becomes more important to diagnose conditions requiring emergent surgical intervention early. We present a case of an elderly male patient with abdominal pain secondary to perforated hollow viscus, subtle evidence of pneumoretroperitoneum on the initial supine abdominal X-ray, and review the signs of pneumoperitoneum and pneumoretroperitoneum on plain abdominal X-rays. 1. Introduction constipation, and vomiting episode may have been associated with consumption of tramadol tablets. There were no prior Perforated hollow viscus may result in pneumoperitoneum episodes of similar symptoms and no identified relieving or pneumoretroperitoneum, depending on the location of factors. He did not have any other associated symptoms perforation along the gastrointestinal tract [1, 2], and may such as fever, change in bowel habits, or history suggesting lead to significant mortality and morbidity. -

Abdominal X-Ray Radiological Signs

Abdominal X-ray Radiological Signs Suzanne O’Hagan Lightbulb moment a moment of sudden inspiration, revelation, or recognition Approach to AXR • Bowel gas pattern • Extraluminal air • Soft tissue masses • Calcifications Normal AXR Liver Gas in stomach Splenic flexure 11th rib T12 Psoas margin Left kidney Hepatic flexure Transverse colon Iliac crest Gas in sigmoid Sacrum Gas in caecum SI joint Bladder Femoral head Gas pattern What is normal? • Stomach – Almost always air in stomach • Small bowel – Usually small amount of air in 2 or 3 loops • Large bowel – Almost always air in rectum and sigmoid – Varying amount of gas in rest of large bowel Normal fluid levels • Stomach – Always (upright, decub) • Small bowel – Two or three levels acceptable (upright, decub) • Large bowel – None normally (functions to remove fluid) Large vs small bowel • Large bowel – Peripheral (except RUQ occupied by liver) – Haustral markings don’t extend from wall to wall • Small bowel – Central – Valvulae conniventes extend across lumen and are spaced closer together Radiographic principles Series of films for acute abdomen • Obstruction series/ Acute abdominal series/ Complete abdominal series – Supine (almost always) – Upright or left decubitus (almost always) – Prone or lateral rectum (variable) – Chest, upright or supine (variable) Acute abdominal series What to look for VIEW LOOK FOR SUPINE ABDOMEN Bowel gas pattern Calcifications Masses PRONE ABDOMEN Gas in rectosigmoid Gas in ascending and descending colon UPRIGHT ABDOMEN Free air, air-fluid levels UPRIGHT -

Imaging of Abnormal Air in the Abdomen and Pelvis

Published online: 2019-07-19 THIEME Review Article 87 Imaging of Abnormal Air in the Abdomen and Pelvis Shobhit Sharma1 Jonathan McDougal2 Tarun Pandey1 Kedar Jambhekar1 Roopa Ram1 1Department of Radiology, University of Arkansas for Medical Address for correspondence Roopa Ram, MD, Department of Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas, United States Radiology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Slot 556, 2Department of Radiology, University of Kansas Medical Center, 4301, West Markham Street, Little Rock, AR 72205, United States Kansas City, Missouri, United States (e-mail: [email protected]). J Gastrointestinal Abdominal Radiol ISGAR 2019;2:87–97 Abstract The presence of abnormal air collection on an imaging study is quite often the reason as well as the solution to a diagnostic dilemma. The purpose of this review article is to Keywords develop an understanding of anatomical localization and determine etiology of abnor- ► air mal air collections in the abdomen and pelvis. Abnormal air collections are commonly ► pneumomediastinum encountered on imaging studies on a daily basis, and this article will help familiarize ► pneumoperitoneum the interpreting radiologist with the pathophysiology of these collections and help ► pneumothorax solve various diagnostic challenges and avoid potential pitfalls. Introduction by dissecting along the vascular sheaths.1 It can extend into the retroperitoneal space via postesophageal areolar The presence of abnormal air collection on an imaging study tissue or aortic hiatus.2 Retroperitoneal air under tension is quite often the reason as well as the solution to a diagnos- can breach parietal peritoneum and thus can present as tic dilemma. The purpose of this review article is to develop intraperitoneal free air.3 Similarly, intraperitoneal and an understanding of anatomical localization and determine retroperitoneal air can extend into the mediastinum. -

Abdominal Extra-Luminal Gas - Is It Always Gastrointestinal Perforation?

Abdominal extra-luminal gas - Is it always gastrointestinal perforation? Poster No.: C-2526 Congress: ECR 2015 Type: Educational Exhibit Authors: M. Barros, L. A. Ferreira, I. Abreu, F. Caseiro Alves; Coimbra/PT Keywords: Abdomen, Conventional radiography, CT, Education, Diagnostic procedure, Education and training DOI: 10.1594/ecr2015/C-2526 Any information contained in this pdf file is automatically generated from digital material submitted to EPOS by third parties in the form of scientific presentations. References to any names, marks, products, or services of third parties or hypertext links to third- party sites or information are provided solely as a convenience to you and do not in any way constitute or imply ECR's endorsement, sponsorship or recommendation of the third party, information, product or service. ECR is not responsible for the content of these pages and does not make any representations regarding the content or accuracy of material in this file. As per copyright regulations, any unauthorised use of the material or parts thereof as well as commercial reproduction or multiple distribution by any traditional or electronically based reproduction/publication method ist strictly prohibited. You agree to defend, indemnify, and hold ECR harmless from and against any and all claims, damages, costs, and expenses, including attorneys' fees, arising from or related to your use of these pages. Please note: Links to movies, ppt slideshows and any other multimedia files are not available in the pdf version of presentations. www.myESR.org Page 1 of 28 Learning objectives • Recognize the presence of extra-luminal gas and its radiological findings to determine its etiologic meaning; • Identify causes of extra-luminal gas in the abdomen that require emergent approach by looking for image signs of underlying pathologic process. -

A Symptom-Based Approach in Internal Medicine

Diagnosis A Symptom-based Approach in Internal Medicine Diagnosis A Symptom-based Approach in Internal Medicine CS Madgaonkar MBBS FCGP Consultant Family Physician Hubli, Karnataka, India Honorary National Professor Indian Medical Association College of General Practitioners Chennai (HQ), Tamil Nadu, India ® JAYPEE BROTHERS MEDICAL PUBLISHERS (P) LTD New Delhi • Panama City • London Published by Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd Corporate Office 4838/24 Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi - 110002, India Phone: +91-11-43574357, Fax: +91-11-43574314 Website: www.jaypeebrothers.com Offices in India • Ahmedabad, e-mail: [email protected] • Bengaluru, e-mail: [email protected] • Chennai, e-mail: [email protected] • Delhi, e-mail: [email protected] • Hyderabad, e-mail: [email protected] • Kochi, e-mail: [email protected] • Kolkata, e-mail: [email protected] • Lucknow, e-mail: [email protected] • Mumbai, e-mail: [email protected] • Nagpur, e-mail: [email protected] Overseas Offices • Central America Office, Panama City, Panama, Ph: 001-507-317-0160, e-mail: [email protected], Website: www.jphmedical.com • Europe Office, UK, Ph: +44 (0) 2031708910, e-mail: [email protected] Diagnosis: A Symptom-based Approach in Internal Medicine © 2011, Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers All rights reserved. No part of this publication should be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author and the publisher. This book has been published in good faith that the material provided by author is original. Every effort is made to ensure accuracy of material, but the publisher, printer and author will not be held responsible for any inadvertent error (s). -

Small Bowel Perforations What the Radiologist Needs to Know

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Università di Palermo Small Bowel Perforations: What the Radiologist Needs to Know Giuseppe Lo Re, MD, Francesca La Mantia, MD, Dario Picone, MD, Sergio Salerno, MD, Federica Vernuccio, MD, and Massimo Midiri, MD The incidence of small bowel perforation is low but can develop from a variety of causes including Crohn disease, ischemic or bacterial enteritis, diverticulitis, bowel obstruction, volvulus, intussusception, trauma, and ingested foreign bodies. In contrast to gastroduodenal perforation, the amount of extraluminal air in small bowel perforation is small or absent in most cases. This article will illustrate the main aspects of small bowel perforation, focusing on anatomical reasons of radiological findings and in the evaluation of the site of perforation using plain film, ultrasound, and multidetector computed tomography equipments. In particular, the authors highlight the anatomic key notes and the different direct and indirect imaging signs of small bowel perforation. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI ]:]]]-]]] C 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction evaluated all CT reports from 2011-2015 searching for “Intestinal Perforation” and reviewed all the images of exams mall bowel perforation is an acute emergency condition in which small bowel perforation was diagnosed. Sdue to a transmural lesion, which affects the full thickness of the bowel wall with the communication of the intestinal lumen with the abdominal cavity and the leakage of intestinal Anatomic Key Notes content.1,2 Early diagnosis, as well as prompt surgical treat- ment, are essential to reduce the morbidity and the mortal- The small bowel lies between the stomach and the large bowel ity.3,4 However, perforation of the small bowel is not a and includes the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.