Emily Fisher Landau, Photographed by Matthew Roberts, in Front of Andy Warhol’S the Shadow (1981)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the City Micol Hebron Chapman University, [email protected]

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Art Faculty Articles and Research Art 1-2008 Women in the City Micol Hebron Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/art_articles Part of the Art and Design Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hebron, Micol. “Women in the City”.Flash Art, 41, pp 90, January-February, 2008. Print. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Faculty Articles and Research by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Women in the City Comments This article was originally published in Flash Art International, volume 41, in January-February 2008. Copyright Flash Art International This article is available at Chapman University Digital Commons: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/art_articles/45 group shows Women in the City S t\:'-: F RA:'-.CISCO in over 50 locations in the Los ments on um screens throughout Museum (which the Guerrilla Angeles region. Nobody walks in the city, presenting images of Girls have been quick to critique LA, but "Women in the City" desirable lu xury items and phrases for its disproportionate holdings of encourages the ear-flaneurs of Los that critique the politics of work by male artists). The four Angeles to put down their cell commodity culture. L{)uisc artists in "Women in the City," phones and lattcs and look for the Lawler's A movie will be shown renowned for their ground billboards, posters, LED screens without the pictures (1979) was re breaking exploration of gender and movie marquis that host the screened in it's original location stereotypes, the power of works in this eJ~;hibition. -

Mapping Robert Storr

Mapping Robert Storr Author Storr, Robert Date 1994 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams ISBN 0870701215, 0810961407 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/436 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art bk 99 £ 05?'^ £ t***>rij tuin .' tTTTTl.l-H7—1 gm*: \KN^ ( Ciji rsjn rr &n^ u *Trr» 4 ^ 4 figS w A £ MoMA Mapping Robert Storr THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK (4 refuse Published in conjunction with the exhibition Mappingat The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 6— tfoti h December 20, 1994, organized by Robert Storr, Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture The exhibition is supported by AT&TNEW ART/NEW VISIONS. Additional funding is provided by the Contemporary Exhibition Fund of The Museum of Modern Art, established with gifts from Lily Auchincloss, Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro, and Mr. and Mrs. Ronald S. Lauder. This publication is supported in part by a grant from The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. Produced by the Department of Publications The Museum of Modern Art, New York Osa Brown, Director of Publications Edited by Alexandra Bonfante-Warren Designed by Jean Garrett Production by Marc Sapir Printed by Hull Printing Bound by Mueller Trade Bindery Copyright © 1994 by The Museum of Modern Art, New York Certain illustrations are covered by claims to copyright cited in the Photograph Credits. -

One of a Kind, Unique Artist's Books Heide

ONE OF A KIND ONE OF A KIND Unique Artist’s Books curated by Heide Hatry Pierre Menard Gallery Cambridge, MA 2011 ConTenTS © 2011, Pierre Menard Gallery Foreword 10 Arrow Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 by John Wronoski 6 Paul* M. Kaestner 74 617 868 20033 / www.pierremenardgallery.com Kahn & Selesnick 78 Editing: Heide Hatry Curator’s Statement Ulrich Klieber 66 Design: Heide Hatry, Joanna Seitz by Heide Hatry 7 Bill Knott 82 All images © the artist Bodo Korsig 84 Foreword © 2011 John Wronoski The Artist’s Book: Rich Kostelanetz 88 Curator’s Statement © 2011 Heide Hatry A Matter of Self-Reflection Christina Kruse 90 The Artist’s Book: A Matter of Self-Reflection © 2011 Thyrza Nichols Goodeve by Thyrza Nichols Goodeve 8 Andrea Lange 92 All rights reserved Nick Lawrence 94 No part of this catalogue Jean-Jacques Lebel 96 may be reproduced in any form Roberta Allen 18 Gregg LeFevre 98 by electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or information storage retrieval Tatjana Bergelt 20 Annette Lemieux 100 without permission in writing from the publisher Elena Berriolo 24 Stephen Lipman 102 Star Black 26 Larry Miller 104 Christine Bofinger 28 Kate Millett 108 Curator’s Acknowledgements Dianne Bowen 30 Roberta Paul 110 My deepest gratitude belongs to Pierre Menard Gallery, the most generous gallery I’ve ever worked with Ian Boyden 32 Jim Peters 112 Dove Bradshaw 36 Raquel Rabinovich 116 I want to acknowledge the writers who have contributed text for the artist’s books Eli Brown 38 Aviva Rahmani 118 Jorge Accame, Walter Abish, Samuel Beckett, Paul Celan, Max Frisch, Sam Hamill, Friedrich Hoelderin, John Keats, Robert Kelly Inge Bruggeman 40 Osmo Rauhala 120 Andreas Koziol, Stéphane Mallarmé, Herbert Niemann, Johann P. -

Jenny Holzer, Attempting to Evoke Thought in Society

Simple Truths By Elena, Raphaelle, Tamara and Zofia Introduction • A world without art would not only be dull, ideas and thoughts wouldn’t travel through society or provoke certain reactions on current events and public or private opinions. The intersection of arts and political activism are two fields defined by a shared focus of creating engagement that shifts boundaries, changes relationships and creates new paradigms. Many different artists denounce political issues in their artworks and aim to make large audiences more conscious of different political aspects. One particular artist that focuses on political art is Jenny Holzer, attempting to evoke thought in society. • Jenny Holzer is an American artist who focuses on differing perspectives on difficult political topics. Her work is primarily text-based, using mediums such as paper, billboards, and lights to display it in public spaces. • In order to make her art as accessible to the public, she intertwines aesthetic art with text to portray her political opinions from various points of view. The text strongly reinforces her message, while also leaving enough room for the work to be open to interpretation. Truisms, (1977– 79), among her best-known public works, is a series inspired by Holzer’s experience at Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program. These form a series of statements, each one representing one individual’s ideology behind a political issue. When presented all together, the public is able to see multiple perspectives on multiple issues. Holzer’s goal in this was to create a less polarized and more tolerant view of our differing viewpoints, normally something that separates us and confines us to one way of thinking. -

Barbara Kruger Born 1945 in Newark, New Jersey

This document was updated February 26, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Barbara Kruger Born 1945 in Newark, New Jersey. Lives and works in Los Angeles and New York. EDUCATION 1966 Art and Design, Parsons School of Design, New York 1965 Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021-2023 Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You, I Mean Me, I Mean You, Art Institute of Chicago [itinerary: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; The Museum of Modern Art, New York] [forthcoming] [catalogue forthcoming] 2019 Barbara Kruger: Forever, Amorepacific Museum of Art (APMA), Seoul [catalogue] Barbara Kruger - Kaiserringträgerin der Stadt Goslar, Mönchehaus Museum Goslar, Goslar, Germany 2018 Barbara Kruger: 1978, Mary Boone Gallery, New York 2017 Barbara Kruger: FOREVER, Sprüth Magers, Berlin Barbara Kruger: Gluttony, Museet for Religiøs Kunst, Lemvig, Denmark Barbara Kruger: Public Service Announcements, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio 2016 Barbara Kruger: Empatía, Metro Bellas Artes, Mexico City In the Tower: Barbara Kruger, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC 2015 Barbara Kruger: Early Works, Skarstedt Gallery, London 2014 Barbara Kruger, Modern Art Oxford, England [catalogue] 2013 Barbara Kruger: Believe and Doubt, Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria [catalogue] 2012-2014 Barbara Kruger: Belief + Doubt, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC 2012 Barbara Kruger: Questions, Arbeiterkammer Wien, Vienna 2011 Edition 46 - Barbara Kruger, Pinakothek -

Wedel Art Collective Launch Face Masks Designed by Leading Artists

Wedel Art Collective launch face masks designed by leading artists: Jenny Holzer, Rashid Johnson, Barbara Kruger, Raymond Pettibon, Lorna Simpson and Rosemarie Trockel Left to right, face masks designed by: Rosemarie Trockel; Jenny Holzer; Lorna Simpson; Barbara Kruger; Raymond Pettibon and Rashid Johnson. Courtesy Wedel Art Collective. Wedel Art Collective have collaborated with six international leading artists to produce a set of unique artist-designed face masks, all proceeds from which will be donated to international relief efforts and artist support for those affected by COVID-19. Launching exclusively on MATCHESFASHION from 24 August the project draws upon the power of contemporary art to encourage more people to wear face masks to protect, and support. Each of the participating artists are internationally celebrated for their work addressing some of the most important social and political issues of our times. Through the inspiration of these artists’ work, the limited-edition face masks reflect the artists’ passionate and urgent response to the pandemic, highlighting the need for community action. Artists include: Jenny Holzer (b. 1950, Ohio, USA); Rashid Johnson (b. 1977, Chicago, USA); Barbara Kruger (b. 1975, New Jersey, USA); Raymond Pettibon (b. 1957, Arizona, USA); Lorna Simpson (b. 1960, New York, USA); and Rosemarie Trockel (b. 1952, Schwerte, Germany). Jenny Holzer's face mask taps into the necessity of mask-wearing, reading “You – Me”. “I like to think of my work as useful,” Holzer says “That is a recurrent impulse, when something happens in the world, if I have an idea that be properly responsive… Not necessarily a cure or a solution but at least an offering.” Raymond Pettibon's mask design features Vavoom, a figure inspired by Felix the Cat that he has drawn since the mid-1980s. -

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

Comparison of Social Criticism in the Works of Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer Master’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Bc. Katarína Belejová Comparison of Social Criticism in the Works of Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr. 2013 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Bc. Katarína Belejová Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr., for his encouragement, patience and inspirational remarks. I would also like to thank my family for their support. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 1. Postmodern Art, Conceptual Art and Social Criticism .............................................. 7 1.1 Social Criticism as a Part of Postmodernity ..................................................................... 7 1.2 Postmodernism, Conceptual Art and Promotion of a Thought .................................. 9 1.2. Importance of Subversion and Parody ........................................................................... 12 1.3 Conceptual Art and Its Audience ...................................................................................... 16 2. American context ..................................................................................................... 21 2.1 The 1980s in the USA ......................................................................................................... -

WHITNEY Education

WHITNEY Education Jenny Holzer: PROTECT PROTECT March 12 - May 31, 2009 Pre- and Post-Visit Materials for Teachers How can these materials be used? These materials provide a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offer suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts. I. About the Artist II. About the Exhibition III. Pre-Visit Activities IV. Post-Visit Activities V. Bibliography & Links What grade levels are these Pre- and Post-Visit materials intended for? These lessons and activities have been written for High School students. We encourage you to adapt and build upon them in order to meet your teaching objectives and students’ needs. Please note that a portion of the exhibition includes declassified and other sensitive government documents that reference war, detainees, torture, homicide, filial relationships, arms, and the oil trade. There is adult language in the exhibition. We recommend that you visit the museum in advance of bringing your students to prepare for questions that might arise from the exhibition's content. We are happy to send you an Educator pass so that you can preview the exhibition. Please email [email protected] if you would like to request one. At the Museum Guided Visits We invite you and your students to visit the Whitney. To schedule a guided tour, please visit www.whitney.org/education. If you are scheduled for a guided school group tour, your museum educator will contact you prior to your visit. -

Contact: Karen Frascona Grace Munns 617.369.3442 617.369.3045 [email protected] [email protected]

Maud Morgan Prize – Annette Lemieux, p. 1 Contact: Karen Frascona Grace Munns 617.369.3442 617.369.3045 [email protected] [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON, AWARDS 2017 MAUD MORGAN PRIZE, HONORING A MASSACHUSETTS WOMAN ARTIST, TO ANNETTE LEMIEUX BOSTON (January 31, 2017)—The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), announced today that Boston-based Annette Lemieux (born 1957) is the recipient of its 2017 Maud Morgan Prize, which honors a Massachusetts woman artist who has demonstrated creativity and vision, and who has made significant contributions to the contemporary arts landscape. Ranging from painting to photography to found-object assemblage, Lemieux’s conceptual works confront urgent subjects such as the horror of war, the nature of time, the elusive truth of memory and the relationship between personal experience and cultural history. Currently a Senior Lecturer on Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University, she has influenced younger generations of artists as a teacher for more than 20 years. The Museum has collected Lemieux’s works since the late 1980s, cultivating a sustained belief in her practice. As part of the Prize, the artist will receive a $10,000 award, and an exhibition of her work will be Annette Lemieux presented at the MFA in the summer. “Annette is fearless about tackling timely socio-political issues in her artwork. She is a careful observer of the world and a thoughtful commentator on important issues of our time,” said Matthew Teitelbaum, Ann and Graham Gund Director of the MFA. “We look forward to working closely with her and sharing her voice with a wide and appreciative public.” Born in Norfolk, Virginia, Lemieux received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting from the Hartford Art School, University of Hartford in 1980. -

(Inaudible) Set up for Jenny Holzer. Can You Hear Me?

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-to-Reel collection Jenny Holzer, 1990 PART 1 DIANE WALDMAN — (inaudible) set up for Jenny Holzer. Can you hear me? AUDIENCE Yes. DIANE WALDMAN Okay. Good evening. I’d like to welcome you to the Guggenheim Museum. I am Diane Waldman, curator of the Jenny Holzer exhibition. Before I introduce the artist, I would like to make a few brief comments on her work, and her background. It is now over a decade since Jenny Holzer began to communicate her messages on modern culture, in both indoor and outdoor spaces. Born in Ohio, Jenny studied painting as an undergraduate, and at graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design. In 1977, she moved to New York, and began to work with language as her primary medium. The installation that you see at the Guggenheim was conceived especially for the space. It includes [00:01:00] (audio drops; inaudible) a series of red granite benches which you have seen on the main floor, and another series of white benches for what we call the High Gallery. Coinciding with this exhibition is another exhibition based on her series, the Laments, which I would urge you all to see, if you have not already done so, at the Dia Art Foundation. I would also like to point out that Jenny will be the first woman to represent the United States at next summer’s Venice Biennale, and that audiences there will have an opportunity to see yet another body of work. And now it gives me great pleasure to introduce the artist to you, Jenny Holzer. -

Jenny Holzer.Pdf

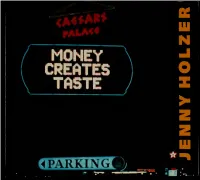

rAi*<« MONEY H : *: l i * TASTE SPARKING JENNY HOLZER OLZ Diane Waldman Chiat This exhibition is supported in part by generous funds from Jay and the National Endowment for the Arts Additional assistance has been provided by The Owen Cheatham Foundation, The Merrill G and the Arts Emita E. Hastings Foundation, the New York State Council on and anonymous donors SOLO/WON R. GUGGENHEIM AAUSEUAA, NEW YORK HARRY N. ABRAAAS, INC., PUBLISHERS, NEW YORK Published by The Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation, Jenny Holzer Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York New York, in association with Harry N Abrams, Incorporated. December 12, 1989-February 11, 1990 New York, a Times Mirror Company. Project organization and production Copyright g 1989 by The Solomon R. Guggenheim Curator Foundation. New York Diane Waldman Coordination and Research Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clare Bell Waldman, Diane Editorial Jenny Holzer Carol Fuerstem Diana Murphy Catalog of an exhibition Includes bibliographical references Design 1 Holzer, Jenny, 1950- -Exhibitions Malcolm Grear Designers I Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum II. Title Special Photography N6537H577A4 1989 709'. 2 89-25747 David Heald ISBN 0-89207-068-4 Project Financial Management Heidi Olson cover Installation Sunrise Systems, Inc. Selections from Truisms 1986 Myro Riznyck Dectronic Starburst double-sided electronic display signboard, Scott Wixon 20 x 40' Timothy Ross Installation, Caesar's Palace, Las Vegas Guggenheim Operations and Maintenance Staff Lara Rubin, assistant to Jenny Holzer Organized