Sustainable Trade and Management of Forest Products and Services in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2019 Lovell’S Shook Industry by Catherine Stone

Yesterday’s News Published quarterly by the Lovell Historical Society Volume 26, Number 4 Fall 2019 Lovell’s Shook Industry By Catherine Stone Hauling apples in barrels made in Lovell The early settlers of Lovell were an industrious had flat headings or ends. They primarily made casks, lot - clearing land, cultivating fields, and harvesting barrels, buckets, vats, firkins, and troughs. timber. In the process, small farms made many of By the 1830s, barrel making was an important their daily necessities, including wooden containers. industry in Lovell. The business was called the shook These containers were used for storage and to transport industry because of the way the wood was bundled goods. This was before the advent of plastics, stainless together for transport. The staves and headings were steel, and corrugated cardboard. formed into barrels or boxes and then dismantled. Making wooden containers was not just a result of Next, they would bundle them together into a kit for necessity. It also became a source of cash money. The shipping. In the process of bundling the wood, they people making the containers as a profession were would shake the material. Shook bundles took up less called coopers. They would make wooden, staved space for shipping. vessels, held together with wooden or metal hoops that Charlotte Hobbs (1879-1968), one of Lovell’s (continued on page 3) From the President This summer was extremely busy and very enjoyable. We hosted two events—our Summer Fair and our biennial House Tour—and were fortunate to have the assistance of a great summer intern, Jonathan Fall Harvest Festival Griggs. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

Reorienting Systematic Conservation Assessment for Effective Conservation Planning

Contributed Paper Reorienting Systematic Conservation Assessment for Effective Conservation Planning BRENT J. SEWALL,∗†‡¶ AMY L. FREESTONE,† MOHAMED F. E. MOUTUI,§ NASSURI TOILIBOU,§ ISHAKA SA¨ID,§ SAINDOU M. TOUMANI,§ DAOUD ATTOUMANE,§ AND CHEIKH M. IBOURA§ ∗Department of Wildlife, Fish, and Conservation Biology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, U.S.A. †Department of Biology, Temple University, 1900 N. 12th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19122, U.S.A. ‡Action Comores International, The Old Rectory, Stansfield, Suffolk CO10 8LT, United Kingdom §Action Comores antenne Anjouan, B.P. 279, Mutsamudu, Anjouan, Union of the Comoros, Western Indian Ocean Abstract: Systematic conservation assessment (an information-gathering and prioritization process used to select the spatial foci of conservation initiatives) is often considered vital to conservation-planning efforts, yet published assessments have rarely resulted in conservation action. Conservation assessments may lead more directly to effective conservation action if they are reoriented to inform conservation decisions. Toward this goal, we evaluated the relative priority for conservation of 7 sites proposed for the first forest reserves in the Union of the Comoros, an area with high levels of endemism and rapidly changing land uses in the western Indian Ocean. Through the analysis of 30 indicator variables measured at forest sites and nearby villages, we assessed 3 prioritization criteria at each site: conservation value, threat to loss of biological diversity from human activity, and feasibility of reserve establishment. Our results indicated 2 sites, Yim´er´eand Hassera-Ndreng´e, were priorities for conservation action. Our approach also informed the development of an implementation strategy and enabled an evaluation of previously unexplored relations among prioritization criteria. -

Historic Douglas-Fir Colonization and Land Use

HISTORIC DOUGLAS-FIR COLONIZATION AND LAND USE PRACTICES AT PRESERVATION SITES NEAR EUGENE, OR by WADE MARTIN A THESIS Presented to the Department of Environmental Science and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science June 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Daniel Gavin for his insight in so many different disciplines of study that advised the completion of this project. Thank you to the members of my defense panel, Professors Margaret Boulay and Casey Shoop, for the positive reinforcement and valuable diversity of perspective offered to this project. I would like to extend an equally important acknowledgement to the members of the Nature Conservancy Willamette Valley Field Office for providing access to information integral to my studies on the Eugene area conservation sites as well as permission to extract specimen from the Willow Creek, Coburg Ridge, and Willamette Confluence preserves. Without your help, this project would not have been possible. Thank you to Professors Mark Carey, Kevin Hatfield, and Jennifer O’Neal for aiding my research on Kalapuya culture; and my honors advisor Ocean Howell for his assistance along the way. Thank you to my father for enduring the coring sessions, my mother and grandparents for keeping my morale up, my brother for his keen and polished eye for revision, and all of my friends for making these four years unforgettable. iii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Historic Willamette Valley Vegetation Cover 2 Indigenous -

Northern Mozambique Channel Seascape

WWF MDCO priority landscapes NEWSLETTER FACTSHEET APRIL Northern Mozambique Channel Seascape 2016 A hotspot of marine and coastal biodiversity and one of the last large marine sanctuaries in the Western Indian Ocean © WWF / Iñaki Relanzon AT A GLANCE Promoting integrated ocean management for sustainable development • Size: 800,000 km² The Northern Mozambique Channel (NMC) region is one of world’s outstanding marine and terrestrial biodiversity areas and a biological reservoir for all East African coastal areas. The • Population: 10 biological and conservation values of the NMC area are of global importance as confirmed by million multiple reports including the 2012 assessment of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Areas (EBSAs). • Ecosystems: coral The economic importance of the NMC has emerged as a future driver of national and regional reefs, mangroves, development on a scale not previously realized in East Africa, due to the high fishery productivity coastal wetlands, of the Mozambique Channel, recent findings of globally significant natural gas deposits and a high seagrasses, islands potential for coastal tourism development. Accelerating population growth in the NMC region (rising and islets, deep to 20 million, by 2040) will increase demands for and pressures on resources, while at the same time ocean, coastal forests providing opportunities for economic growth and building prosperity. • Landscape The region is characterized by lackluster governance of marine resources, including low capacity, features: the second weak law -

Reconsidering the Process for Bow-Stave Removal from Juniper Trees in the Great Basin

Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 37, No. 2 (2017) | pp. 125–131 Reconsidering the Process for Bow-Stave Removal from Juniper Trees in the Great Basin CONSTANCE I. MILLAR USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station 800 Buchanan St., Albany, CA, 94710, USA KEVIN T. SMITH USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station 271 Mast Road, Durham, NH, 03824, USA In 1988, Wilke described juniper trees in the Great Basin from which bow staves had been removed, and suggested the method that had likely been employed to do so. Based upon our own knowledge of tree growth and responses to wounding, we question certain of his assumptions, and offer modifications to Wilke’s proposal as to how prospective staves might have been removed. Further research and experimentation is encouraged. N A CLASSIC PAPER ON GREAT BASIN ARCHEOLOGY, question that the scarred trees were used for bow-stave IWilke (1988) integrated information from ethnography, extraction, nor do we question other aspects developed by knowledge of indigenous practices of tool fabrication and Wilke (1988) about stave harvesting methods. use, and extensive field observations of trees that had been anthropogenically wounded to propose a process by which prospective bow staves were removed from SUMMARY OF WILKE’S (1988) KEY trees. Based on our knowledge of tree growth and wound OBSERVATIONS AND PROCESSES response, and our own field observations of scarred trees FOR BOW-STAVE REMOVAL (CIM: December 2016, Long Valley, California and Little Based on extensive observation of intentionally scarred Whisky Flat, Nevada), we question several premises trees in the western Great Basin, Wilke (1988) described that underlie Wilke’s (1988) proposed mechanism. -

Specification Considerations for Architectural Wood Doors

CONTINUING EDUCATION SPECIFICATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR Presented by: ARCHITECTURAL WOOD DOORS LEARNING OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this course the student will be able to: 1. Identify components of an architectural wood door. 2. Increase awareness of wood door assembly and construction. 3. Provide a better understanding of industry standards and new door technology. 4. Review how to specify doors to meet project requirements. CONTINUING EDUCATION CREDIT: 1 LU COURSE NUMBER: ARjuly2016.3 Use the learning objectives above to focus your study as you read this article. To earn credit and obtain a certificate of completion, visit http://go.hw.net/AR716Course3 and complete the quiz for free as you read this article. If you are new to Hanley Wood University, create a free learner account; returning users log in as usual. ENDLESS CREATIVE POTENTIAL WITH All doors consist of a core, stiles, rails, and face ARCHITECTURAL WOOD DOORS materials. Crossbanding and backers may be applied, depending on the construction process. Architectural wood doors command attention with their distinctive elegance. Whether you’re The core is the innermost layer or section in envisioning something understated or wildly component construction. Core types include exotic, extensive wood veneer options, as well particleboard, structural composite lumber as a variety of factory and custom finishes will (SCL), staved lumber, agrifiber, and fire resistant open your eyes to endless creative possibilities. composite. Stiles are the upright or vertical But, taking all design and performance pieces of the core assembly of a wood flush All doors consist of a core, stiles, rails, and face materials. options into consideration when specifying the Crossbanding and backers may be applied, depending on the door, while rails are the top and bottom edge construction process. -

Impacts of Land Use on Biodiversity: Development of Spatially Differentiated Global Assessment Methodologies for Life Cycle Assessment

DISS. ETH NO. xx Impacts of land use on biodiversity: development of spatially differentiated global assessment methodologies for life cycle assessment A dissertation submitted to ETH ZURICH for the degree of Doctor of Sciences presented by LAURA SIMONE DE BAAN Master of Sciences ETH born January 23, 1981 citizen of Steinmaur (ZH), Switzerland accepted on the recommendation of Prof. Dr. Stefanie Hellweg, examiner Prof. Dr. Thomas Koellner, co-examiner Dr. Llorenç Milà i Canals, co-examiner 2013 In Gedenken an Frans Remarks This thesis is a cumulative thesis and consists of five research papers, which were written by several authors. The chapters Introduction and Concluding Remarks were written by myself. For the sake of consistency, I use the personal pronoun ‘we’ throughout this thesis, even in the chapters Introduction and Concluding Remarks. Summary Summary Today, one third of the Earth’s land surface is used for agricultural purposes, which has led to massive changes in global ecosystems. Land use is one of the main current and projected future drivers of biodiversity loss. Because many agricultural commodities are traded globally, their production often affects multiple regions. Therefore, methodologies with global coverage are needed to analyze the effects of land use on biodiversity. Life cycle assessment (LCA) is a tool that assesses environmental impacts over the entire life cycle of products, from the extraction of resources to production, use, and disposal. Although LCA aims to provide information about all relevant environmental impacts, prior to this Ph.D. project, globally applicable methods for capturing the effects of land use on biodiversity did not exist. -

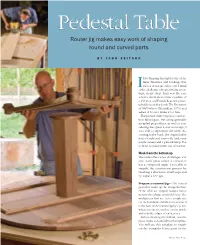

Pedestal Table Router Jig Makes Easy Work of Shaping Round and Curved Parts

Pedestal Table Router jig makes easy work of shaping round and curved parts BY JOHN ZEITOUN love flipping through books of an- tique furniture and looking over I pieces at garage sales, and I jump at the challenge of reproducing an an- tique in my shop. Such was the case when a client showed me a picture of a 160-year-old French Regency pedes- tal table from the book The Furniture of Old Ontario (Macmillan, 1973) and asked if I could make it for him. The picture didn’t explain construc- tion techniques, but using generally accepted proportions, as well as con- sidering the space it was to occupy, I was able to reproduce the table. Ac- cording to the book, the original table had a hardwood base with bird’s-eye maple veneer and a pine tabletop. But I chose to make mine out of walnut. Work from the bottom up The table offers a few challenges. For one, each piece either is curved or has a compound angle. I was able to simplify the construction process by breaking it down into small steps and by using a few jigs. Prepare a trammel jig— The curved parts that make up the triangular base of the table are shaped using a router mounted to a large trammel device. The workpieces first are cut to rough size on the bandsaw and then are screwed to the base of the trammel jig (see p. 62), where a router is used to cut the inside and outside edges of each piece. Before shaping the walnut, use the jig to make a particleboard template. -

Creating Woodturnings That Incorporate Slanted Staves This Article Is About Creating Woodturnings Incorporating Slanted Stave Elements

Creating Woodturnings that incorporate Slanted Staves This article is about creating woodturnings incorporating slanted stave elements. Since this is an extension of the segmented vessel process let’s start by comparing three methods of creating segmented vessels used by turners to create pieces of art using multiple pieces of wood in combination. There other forms of the segmented art, but the three we’ll discuss are: 1. Rings of staves 2. Rings of segments 3. Slanted stave rings Rings of Simple staves – those with straight sides – are a simple construction in which the key to success is to accurately make the two key elements – angle and width of the stave – close into a stave ring with no gap. The angle is derived by a simple formula dividing 360° by the number of staves. Then for convenience to divide that by 2 to set your saw’s bevel angle for two cuts. Hence, a stave construction of 8 staves would require dividing 360 by 8 to get 45° and then dividing that by 2 to get two equal cuts of 22.5°. Once you know what you’re accomplishing you can use the short form of this to divide 180° by the number of staves. The width of the stave can be roughly determined by dividing the circumference by the number of staves in the ring. For example: A ring of 8 staves with a circumference of 24” would seem to require 8 staves of 3” width. Actually due to the geometry of the ring and the flat cut staves, if you were to follow the above formula the finished circumference of your ring would be less than 24” – in fact close to 22 ¾”. -

Ruin, Resistance and Renewal in a Qom Community of Northern Argentina

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Fighting With Wine: Ruin, Resistance and Renewal in a Qom Community of Northern Argentina Christopher A. Golias University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Golias, Christopher A., "Fighting With Wine: Ruin, Resistance and Renewal in a Qom Community of Northern Argentina" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1741. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1741 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1741 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fighting With Wine: Ruin, Resistance and Renewal in a Qom Community of Northern Argentina Abstract This study examines public binge drinking among the Qom (Toba) ex-foragers of Formosa, northern Argentina. Based upon 15 months of ethnographic fieldwork in a peri-urban Qom barrio (Lot 84), this analysis relates binge drinking to Qom ethnohistory, community life, and interactions with the Argentine state. The public, performative nature of Qom binge drinking is explored; intoxication is shown to convey in sometimes violent public spectacle the pathos of their socioeconomic marginality, reinforce non- indigenous Argentines’ entrenched perceptions of violent “Indians”, and paradoxically provide the Qom with vehicle for continued colonial resistance. Many Qom view drinking problems as rooted in Lot 84’s close proximity to the city (Formosa) relative to more rural Qom villages. Thus they reference a continuum of health that runs from urban, non-indigenous spaces to the rural bush country where foods—including home-brewed alcohol—are healthful rather than harmful. -

Rapport D'activités 2015

Rapport d’activités 2015 Juillet 2016 ONG Dahari Mutsamudu, Anjouan, Comores Table des matières A propos de l’ONG Dahari .......................................................................................................................................2 Résumé ...........................................................................................................................................................................4 Summary .........................................................................................................................................................................5 Dahari en chiffres .........................................................................................................................................................6 1. Introduction au rapport .........................................................................................................................................7 2. Développement de partenariats techniques .....................................................................................................8 3. Nouveaux bailleurs ............................................................................................................................................... 11 4. Rapport des activités de terrain 2015 ............................................................................................................. 12 4.1. Volet agricole ................................................................................................................................................