An Online Journal of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abulad, Philosophy, and Intellectual Generosity

K R I T I K E An Online Journal of Philosophy Volume 13, Number 2 December 2019 ISSN 1908-7330 THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY University of Santo Tomas Philippine Commission on Higher Education COPYRIGHTS All materials published by KRITIKE are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License KRITIKE supports the Open Access Movement. The copyright of an article published by the journal remains with its author. The author may republish his/her work upon the condition that KRITIKE is acknowledged as the original publisher. KRITIKE and the Department of Philosophy of the University of Santo Tomas do not necessarily endorse the views expressed in the articles published. © 2007-2019 KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy | ISSN 1908-7330 | OCLC 502390973 | [email protected] ABOUT THE COVER KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy, 13:2 (December 2019) Paolo A. Bolaños, Gelassenheit, 2010. Photograph. About the Journal KRITIKE is the official open access (OA) journal of the Department of Philosophy of the University of Santo Tomas (UST), Manila, Philippines. It is a Filipino peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary, and international journal of philosophy founded by a group of UST alumni. The journal seeks to publish articles and book reviews by local and international authors across the whole range of philosophical topics, but with special emphasis on the following subject strands: • Filipino Philosophy • Oriental Thought and East-West Comparative Philosophy • Continental European Philosophy • Anglo-American Philosophy The journal primarily caters to works by professional philosophers and graduate students of philosophy, but welcomes contributions from other fields (literature, cultural studies, gender studies, political science, sociology, history, anthropology, economics, inter alia) with strong philosophical content. -

In This Issue of KRITIKE: an Online Journal of Philosophy

KRITIKE VOLUME FIVE NUMBER ONE (JUNE 2011) i-iv Editorial In this Issue of KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy Paolo A. Bolaños 011 is an important year for KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy. This year marks the transition of the journal from a purely 2 independent professional open access journal of philosophy to being the official academic journal of the Department of Philosophy of the University of Santo Tomas. This transition prompted a process of streamlining our editorial procedures and the invitation of new members to the editorial board. We welcome these developments for they are signs of the journal’s maturity. Along with this maturity are the recent recognition by Humanities International Complete™ (EBSCO Publishing) and the Modern Languages Association Directory of Periodicals, wherein KRITIKE is now abstracted and indexed. This ninth issue features papers that deal with Filipino philosophy, philosophical anthropology, issues about time and consciousness, political philosophy, hermeneutics, and aesthetics. A book review of a book about religion in the public sphere is also included. The first two essays are written in Filipino, which is the way the authors attempt to articulate, or create, what they think is Filipino Philosophy. For his part, F.P.A. Demeterio offers a recount of the respective hermeneutics of Friedrich Schleiermacher and Wilhelm Dilthey, two foundational theorists in the hermeneutical tradition, in a paper called “Ang Hermenyutika nina Friedrich Schleiermacher at Wilhelm Dilthey bilang Batayang Teoretikal sa Araling Pilipino.” The purpose of Demeterio’s recount is the attempt to contextualize the study, and use, of the hermeneutical methods of Schleiermacher and Dilthey within the broader scope of Philippine Studies, but more specifically, in the study of local texts and culture. -

How Kristo Democratized Langit: the Discourse of Liberation in Christianized Katagalugan

K R I T I K E An Online Journal of Philosophy Volume 5, Number 1 June 2021 ISSN 1908-7330 THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY University of Santo Tomas Philippine Commission on Higher Education COPYRIGHTS All materials published by KRITIKE are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License KRITIKE supports the Open Access Movement. While an article published by Kritike is under the CC BY- NC-ND license, users are allowed to download and use the article for non-commercial use (e.g., research or educational purposes). Users are allowed to reproduce the materials in whole but are not allowed to change their contents. The copyright of an article published by the journal remains with its author; users are required to acknowledge the original authorship. The author of an article has the right to republish his/her work (in whole, in part, or in modified form) upon the condition that Kritike is acknowledged as the original publisher. KRITIKE and the Department of Philosophy of the University of Santo Tomas do not necessarily endorse the views expressed in the articles published. © 2007-2021 KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy | ISSN 1908-7330 | OCLC 502390973 | [email protected] ABOUT THE COVER “Tunnels” This photo is taken from a German town along the Rhine River. A tunnel serves various purposes: as passage for people, animals, vehicles, and trains, but also for utility as passage for water or cables. A tunnel is both alive and not as it is filled with such vitality but remains cold and dark through its nonhumanness. -

Russian Nationalism

Russian Nationalism This book, by one of the foremost authorities on the subject, explores the complex nature of Russian nationalism. It examines nationalism as a multi layered and multifaceted repertoire displayed by a myriad of actors. It considers nationalism as various concepts and ideas emphasizing Russia’s distinctive national character, based on the country’s geography, history, Orthodoxy, and Soviet technological advances. It analyzes the ideologies of Russia’s ultra nationalist and far-right groups, explores the use of nationalism in the conflict with Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea, and discusses how Putin’s political opponents, including Alexei Navalny, make use of nationalism. Overall the book provides a rich analysis of a key force which is profoundly affecting political and societal developments both inside Russia and beyond. Marlene Laruelle is a Research Professor of International Affairs at the George Washington University, Washington, DC. BASEES/Routledge Series on Russian and East European Studies Series editors: Judith Pallot (President of BASEES and Chair) University of Oxford Richard Connolly University of Birmingham Birgit Beumers University of Aberystwyth Andrew Wilson School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London Matt Rendle University of Exeter This series is published on behalf of BASEES (the British Association for Sla vonic and East European Studies). The series comprises original, high quality, research level work by both new and established scholars on all aspects of Russian, -

J-Gate Social

J-Gate Social Sciences & Humanities Journal List 2 @ this point 3 @ctivités 4 @tic.Revista d'innovació Educativa 6 1611: A Journal of Translation History 7 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century 9 3C Empresa 10 3CMedia 11 3L: Language, Linguistics, Literature 13 417 Magazine 14 49th Parallel 18 A|Z ITU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture 21 AALL Spectrum 22 AASA Journal of Scholarship and Practice 25 AAUP Journal of Academic Freedom 30 Abbey Newsletter 31 ABC Journal of Advanced Research 32 ABC Research Alert 34 Abhath Al-Yarmouk 36 Abhinav-International Monthly Refereed Journal of Research in Management and Technology 37 Abhinav-National Monthly Refereed Journal of Research in Arts and Education 38 Abhinav-National Monthly Refereed Journal of Research in Commerce and Management 39 Abnormal and Behavioural Psychology 43 Aboriginal Policy Studies 46 Abstract: Language, Mind and Action 49 Academe 51 Academia and Society 52 Academia Economic Papers 53 Academia Journal of Educational Research 56 Academic Journal of Business, Administration, Law and Social Sciences 57 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 58 Academic Journal of Knowledge and Research of Law 59 Academic Journal of Management Sciences 60 Academic Journal of Research in Business and Accounting 63 Academic Research International 64 Academic Research Journal of Psychology and Counselling 65 Academic Sight 66 Academica Turistica - Tourism and Innovation Journal 68 Academicus 69 Academy Journal of Educational Sciences 71 Academy of Contemporary Research -

Publication Ethics and Malpractice Statement

K R I T I K E An Online Journal of Philosophy Volume 12, Number 2 December 2018 ISSN 1908-7330 THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY University of Santo Tomas Philippine Commission on Higher Education COPYRIGHTS All materials published by KRITIKE are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License KRITIKE supports the Open Access Movement. The copyright of an article published by the journal remains with its author. The author may republish his/her work upon the condition that KRITIKE is acknowledged as the original publisher. KRITIKE and the Department of Philosophy of the University of Santo Tomas do not necessarily endorse the views expressed in the articles published. © 2007-2018 KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy | ISSN 1908-7330 | OCLC 502390973 | [email protected] ABOUT THE COVER KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy, 12:2 (December 2018) Roland Theuas DS. Pada, Parasol, 2018. Photograph. About the Journal KRITIKE is the official open access (OA) journal of the Department of Philosophy of the University of Santo Tomas (UST), Manila, Philippines. It is a Filipino peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary, and international journal of philosophy founded by a group of UST alumni. The journal seeks to publish articles and book reviews by local and international authors across the whole range of philosophical topics, but with special emphasis on the following subject strands: • Filipino Philosophy • Oriental Thought and East-West Comparative Philosophy • Continental European Philosophy • Anglo-American Philosophy The journal primarily caters to works by professional philosophers and graduate students of philosophy, but welcomes contributions from other fields (literature, cultural studies, gender studies, political science, sociology, history, anthropology, economics, inter alia) with strong philosophical content. -

CHED, DOH, IATF-EID, Manila LGU Inspect

Manila City Mayor Hon. Francisco “Isko Moreno” CHED-NCR Education Supervisor Victor Castelo Domagoso (right) signs the University guest book, (second from left) inspects medical learning aids. with UST Secretary-General Rev. Fr. Jesús M. Miranda, Jr., O.P. INSIDE: CHED, DOH, IATF-EID, Health Secretary Duque visits UST Hospital’s Manila LGU inspect UST; ceremonial vaccination against COVID-19 3 Thirty-eight obtain degree in Sacred Theology from UST Faculty of Sacred discussions on limited Theology-Catholic in-person classes for medical University of Korea aggregation 4 Newton-UST Research Team presents research students held output to Santa Rosa, Laguna LGU 6 anila City Mayor Francisco “Isko Moreno” Domagoso, accompanied Medallon of CRS tackles OT interns’ attitude by Vice Mayor and UST alumna Honey Lacuña, and representatives development in research presentation 9 from the Commission on Higher Education (CHED), the Department Mof Health (DOH) and Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious UST holds media training workshop with Diseases (IATF-EID), visited UST on February 26, 2021, to look at the renowned journalist Armie Jarin-Bennett, retrofitted classrooms, and for a discussion on how in-person classes would award-winning writer Jowie De Los Reyes 12 be conducted. Amid stringent safety and disinfection protocols to combat the ongoing UST Grad School - Educ Cluster webinar pandemic, UST intended to start in-person instruction for its medical and presents emerging designs, uses of Qualitative Research 15 LIMITED IN-PERSON CLASSES TO PAGE 2 and more ... News News LIMITED IN-PERSON CLASSES FROM PAGE 1 Health Secretary Duque visits UST Hospital’s ceremonial vaccination against COVID-19 epartment of Health Secretary Dr. -

EDS E-Resource Analysis Template

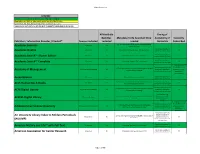

Major Resources LEGEND: SEARCHES FULL TEXT OF RESOURCE (ALL CONTENT LOADED) SEARCHES FULL TEXT OF RESOURCE (AWAITING CONTENT LOAD) RESOURCES ARE INDEXED (EDS DOES NOT SEARCH FULL TEXT) *RESOURCES NOT ON THIS LIST ARE NOT CURRENTLY SEARCHABLE USING EDS All Available Timing of Backfiles Metadata To Be Searched Once Availability of Currently Publisher / Information Provider / Product* Sources Included Included Loaded Metadata Subscribed Full Text Searching for All Journals including all available All journals Yes Academic Journals Subject Headings Y Everything is loaded and All sources Yes All available indexing, abstracts, TOC, and full text Academic Onefile available now for end users Y Everything is loaded and All sources Yes All indexing, abstracts, TOC, and full text Academic Search™ Alumni Edition available now for end users Y Everything is loaded and All sources Yes All indexing, abstracts, TOC, and full text Academic Search™ Complete available now for end users Y Y – Publications from Everything provided by the this publisher are Full Text Searching for All Journals & Proceedings including all All journals and proceedings Yes publisher is loaded and accessed via your Academy of Management available Subject Headings available now for end users EBSCOhost subscriptions Everything is loaded and All sources Yes All available metadata and full text AccessScience available now for end users Y Full Text Searching for all eBooks with Additional Metadata Everything is loaded and All eBooks Yes ACLS Humanities E-Books Provided through MARC -

An Online Journal of Philosophy

K R I T I K E An Online Journal of Philosophy Volume 9, Number 2 December 2015 ISSN 1908-7330 K R I T I K E An Online Journal of Philosophy Volume 9, Number 2 December 2015 ISSN 1908-7330 THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY University of Santo Tomas Philippine Commission on Higher Education COPYRIGHTS All materials published by KRITIKE are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License KRITIKE supports the Open Access Movement. The copyright of an article published by the journal remains with its author. The author may republish his/her work upon the condition that KRITIKE is acknowledged as the original publisher. KRITIKE and the Department of Philosophy of the University of Santo Tomas do not necessarily endorse the views expressed in the articles published. © 2007-2015 KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy | ISSN 1908-7330 | OCLC 502390973 | [email protected] ABOUT THE COVER KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy, 9:2 (December 2015) Roland Theuas DS. Pada, Alley, 2015. Photograph. About the Journal KRITIKE is the official open access (OA) journal of the Department of Philosophy of the University of Santo Tomas (UST), Manila, Philippines. It is a Filipino peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary, and international journal of philosophy founded by a group of UST alumni. The journal seeks to publish articles and book reviews by local and international authors across the whole range of philosophical topics, but with special emphasis on the following subject strands: Filipino Philosophy Oriental Thought and East-West Comparative Philosophy Continental European Philosophy Anglo-American Philosophy The journal primarily caters to works by professional philosophers and graduate students of philosophy, but welcomes contributions from other fields (literature, cultural studies, gender studies, political science, sociology, history, anthropology, economics, inter alia) with strong philosophical content. -

Ang Etika Sa Búhay Pamilya Ng Mga Filipino at Tsino 48 F.P.A

K R I T I K E An Online Journal of Philosophy Volume 11, Number 1 June 2017 ISSN 1908-7330 THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY University of Santo Tomas Philippine Commission on Higher Education COPYRIGHTS All materials published by KRITIKE are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License KRITIKE supports the Open Access Movement. The copyright of an article published by the journal remains with its author. The author may republish his/her work upon the condition that KRITIKE is acknowledged as the original publisher. KRITIKE and the Department of Philosophy of the University of Santo Tomas do not necessarily endorse the views expressed in the articles published. © 2007-2017 KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy | ISSN 1908-7330 | OCLC 502390973 | [email protected] ABOUT THE COVER KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy, 11:1 (June 2017) Paolo A. Bolaños, Dead Corals, 2017. Photograph. About the Journal KRITIKE is the official open access (OA) journal of the Department of Philosophy of the University of Santo Tomas (UST), Manila, Philippines. It is a Filipino peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary, and international journal of philosophy founded by a group of UST alumni. The journal seeks to publish articles and book reviews by local and international authors across the whole range of philosophical topics, but with special emphasis on the following subject strands: • Filipino Philosophy • Oriental Thought and East-West Comparative Philosophy • Continental European Philosophy • Anglo-American Philosophy The journal primarily caters to works by professional philosophers and graduate students of philosophy, but welcomes contributions from other fields (literature, cultural studies, gender studies, political science, sociology, history, anthropology, economics, inter alia) with strong philosophical content.