Denmark Health Care Systems in Transition I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.International Vs. Intra-National Convergence in Europe

Investigaciones Regionales ISSN: 1695-7253 [email protected] Asociación Española de Ciencia Regional España Cornett, Andreas P.; Sørensen, Nils Karl International vs. Intra-national Convergence in Europe - an Assessment of Causes and Evidence Investigaciones Regionales, núm. 13, 2008, pp. 35-56 Asociación Española de Ciencia Regional Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=28901302 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 02 CORNETT 11/11/08 15:32 Página 35 © Investigaciones Regionales. 13 – Páginas 35 a 56 Sección ARTÍCULOS International vs. Intra-national Convergence in Europe – an Assessment of Causes and Evidence Andreas P. Cornett* and Nils Karl Sørensen** ABSTRACT: The article aims to explain the different patterns of economic deve- lopment in Europe based on an assessment of regional and national performance with regard to innovation, entrepreneurship and difference in the industrial struc- ture. The central hypothesis of the paper is that large intra-regional disparities do not necessarily lead to lower economic growth on the national level than smaller disparities do. On the contrary, the polarization of economic activities can lead to excess growth in some cases, and contribute to a process of convergence between nations. To address the mechanisms behind this process, the long run patterns of convergence and disparities in regional economic performance with regard to GDP and the distri- bution of employment are analyzed on the regional and the national level for selected European countries. -

Referral of Paediatric Patients Follows Geographic Borders of Administrative Units

Dan Med Bul ϧϪ/Ϩ June ϤϢϣϣ DANISH MEDICAL BULLETIN ϣ Referral of paediatric patients follows geographic borders of administrative units Poul-Erik Kofoed1, Erik Riiskjær2 & Jette Ammentorp3 ABSTRACT e ffect of economic incentives rooted in local govern- ORIGINAL ARTICLE INTRODUCTION: This observational study examines changes ment’s interest in maximizing the number of patients 1) Department in paediatric hospital-seeking behaviour at Kolding Hospital from their own county/region who are treated at the of Paediatrics, in The Region of Southern Denmark (RSD) following a major county/region’s hospitals in order not to have to pay the Kolding Hospital, change in administrative units in Denmark on 1 January higher price at hospitals in other regions or in the pri- 2) School of 2007. vate sector. Treatment at another administrative unit is Economics and MATERIAL AND METHODS: Data on the paediatric admis- Management, usually settled with 100% of the diagnosis-related group University of sions from 2004 to 2009 reported by department of paedi- (DRG) value, which is not the case for treatment per - Aarhus, and atrics and municipalities were drawn from the Danish formed at hospitals within the same administrative unit. 3) Health Services National Hospital Registration. Patient hospital-seeking On 1 January 2007, the 13 Danish counties were Research Unit, behaviour was related to changes in the political/admini s- merged into five regions. The public hospitals hereby Kolding Hospital/ trative units. Changes in number of admissions were com- Institute of Regional became organized in bigger administrative units, each pared with distances to the corresponding departments. Health Services with more hospitals than in the previous counties [7]. -

Trade and Investment Factsheets: Denmark

Denmark This factsheet provides the latest statistics on trade and investment between the UK and Denmark. Date of release: 17 September 2021; Date of next planned release: 7 October 2021 Total trade in goods and services (exports plus imports) between the UK and Denmark was £11.6 billion in the four quarters to the end of Q1 2021, a decrease of 16.5% or £2.3 billion from the four quarters to the end of Q1 2020. Of this £11.6 billion: • Total UK exports to Denmark amounted to £5.5 billion in the four quarters to the end of Q1 2021 (a decrease of 10.2% or £626 million compared to the four quarters to the end of Q1 2020); • Total UK imports from Denmark amounted to £6.1 billion in the four quarters to the end of Q1 2021 (a decrease of 21.5% or £1.7 billion compared to the four quarters to the end of Q1 2020). Denmark was the UK’s 22nd largest trading partner in the four quarters to the end of Q1 2021 accounting for 1.0% of total UK trade.1 In 2019, the outward stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) from the UK in Denmark was £6.4 billion accounting for 0.4% of the total UK outward FDI stock. In 2019, the inward stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the UK from Denmark was £7.2 billion accounting for 0.5% of the total UK inward FDI stock.2 1 Trade data sourced from the latest ONS publication of UK total trade data. -

Towards the Kalmar Union

S P E C I A L I Z E D A G E N C I E S TOWARDS THE KALMAR UNION Dear Delegates, Welcome to the 31st Annual North American Model United Nations 2016 at the University of Toronto! On behalf of all of the staff at NAMUN, we welcome you to the Specialized Agency branch of the conference. I, and the rest of the committee staff are thrilled to have you be a delegate in Scandinavia during the High Middle Ages, taking on this challenging yet fascinating topic on the futures of the three Scandinavian Kingdoms in a time of despair, poverty, dependence and competitiveness. This will truly be a new committee experience, as you must really delve into the history of these Kingdoms and figure out how to cooperate with each other without sending everyone into their demise. To begin, in the Towards the Kalmar Union Specialized Agency, delegates will represent influential characters from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, which include prominent knights, monarchs, nobles, and important religious figures who dominate the political, military and economic scenes of their respective Kingdoms. The impending issues that will be discussed at the meeting in Kalmar, Sweden include the future of the Danish and Norwegian crowns after the death of the sole heir to the thrones, Olaf II. Here, two distant relatives to Valdemar IV have a claim to the throne and delegates will need to decide who will succeed to the throne. The second order of business is to discuss the growing German presence in Sweden, especially in major economic cities. -

A Meta Analysis of County, Gender, and Year Specific Effects of Active Labour Market Programmes

A Meta Analysis of County, Gender, and Year Speci…c E¤ects of Active Labour Market Programmes Agne Lauzadyte Department of Economics, University of Aarhus E-Mail: [email protected] and Michael Rosholm Department of Economics, Aarhus School of Business E-Mail: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction Unemployment was high in Denmark during the 1980s and 90s, reaching a record level of 12.3% in 1994. Consequently, there was a perceived need for new actions and policies in the combat of unemployment, and a law Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) was enacted in 1994. The instated policy marked a dramatic regime change in the intensity of active labour market policies. After the reform, unemployment has decreased signi…cantly –in 1998 the unemploy- ment rate was 6.6% and in 2002 it was 5.2%. TABLE 1. UNEMPLOYMENT IN DANISH COUNTIES (EXCL. BORNHOLM) IN 1990 - 2004, % 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 Country 9,7 11,3 12,3 8,9 6,6 5,4 5,2 6,4 Copenhagen and Frederiksberg 12,3 14,9 16 12,8 8,8 5,7 5,8 6,9 Copenhagen county 6,9 9,2 10,6 7,9 5,6 4,2 4,1 5,3 Frederiksborg county 6,6 8,4 9,7 6,9 4,8 3,7 3,7 4,5 Roskilde county 7 8,8 9,7 7,2 4,9 3,8 3,8 4,6 Western Zelland county 10,9 12 13 9,3 6,8 5,6 5,2 6,7 Storstrøms county 11,5 12,8 14,3 10,6 8,3 6,6 6,2 6,6 Funen county 11,1 12,7 14,1 8,9 6,7 6,5 6 7,3 Southern Jutland county 9,6 10,6 10,8 7,2 5,4 5,2 5,3 6,4 Ribe county 9 9,9 9,9 7 5,2 4,6 4,5 5,2 Vejle county 9,2 10,7 11,3 7,6 6 4,8 4,9 6,1 Ringkøbing county 7,7 8,4 8,8 6,4 4,8 4,1 4,1 5,3 Århus county 10,5 12 12,8 9,3 7,2 6,2 6 7,1 Viborg county 8,6 9,5 9,6 7,2 5,1 4,6 4,3 4,9 Northern Jutland county 12,9 14,5 15,1 10,7 8,1 7,2 6,8 8,7 Source: www.statistikbanken.dk However, the unemployment rates and their evolution over time di¤er be- tween Danish counties, see Table 1. -

Member Directory

Member Directory The Delegation of Denmark to the OSCE PA Mr. Peter Juel Jensen Head of Delegation Folketinget Christiansborg 1240 Copenhagen K DENMARK Telephone: +45 61624628 Fax: Political Party Affiliation: The Liberal Party Home District Bornholm Constituency Member of Parliament since 2007 Positions held in Parliament: Vice-chairman of the Environment and Regional Planning Committee from 2007. Member of the Labour Market Committee and the Naturalisation Committee from 2007. Current positions in Parliament: Spokesman for Defense Educational background: Basic vocational education (EFG) and Higher Commercial Examination (HH), Bornholm Vocational School, Rønne 1984- 1987. Other information: Peter Juel Jensen, born May 18th 1966 in Rønne, son of former business manager Jens Juel Jensen and former mayoress Birthe Juel Jensen. Married to Lena Buus Larsen. They have four children Jeppe, born in 2002, Rasmus, born in 2004, Asta-Maria, born in 2006 and Kasper, born in 1991. Profession Teacher, Hjørring College of Education 1996-2000. Officer of the line, Frederiksberg Castle 1991-1993. Chairman for OSCE PA and NATO PA Delegations, Chairman of Countryside Committee Affiliations Chairman of HOC, Principal Organisation of Officers at Frederiksberg Castle, 1992 - 1993. Chairman of the Student Council at Hjørring College of Education, 1996 - 2000. Member of Bornholm County Council, 2001, member of the cultural affairs and social services committee. Member of Aakirkeby Municipal Council, 2001 - 2006, technology and environment committee and the finance committee. Chairman of Bornholm Academy, 2001 - 2007. Chairman of the education council at Åvang School in Rønne, 2002 - 2004. Member of Bornholm Region Council, 2002 - 2007, technology and environment committee, and trade and industry and labour market committee and member of the employment committee, 2005 - 2007, resigned in connection with the 2007 general election. -

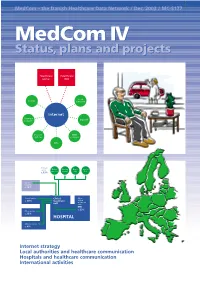

Medcom IV Status, Plans and Projects

MedCom – the Danish Healthcare Data Network / Dec. 2003 / MC-S177 MedComMedCom IV IV Status,Status, plans plans andand projectsprojects Healthcare Healthcare portal DIX Local County authority Internet Pharmacy Dan Net network Doctors’ KMD systems network KPLL Primary sector Medical Nursing Home Specia- practice homes care lists c. 13% Other hospitals c. 10% Clinical service Clinical Other c. 40% treatment clinical treatment unit units EPR c. 23% Other service c. 13% HOSPITAL Administration c. 4% ● Internet strategy ● Local authorities and healthcare communication ● Hospitals and healthcare communication ● International activities 2 MedCom IV – status, plans and projects Contents Aims of MedCom 2 The local authorities and healthcare communication 20 Introduction 3 The Hospital-Local Authority XML project 20 Healthcare on the move 3 The Hospital-Local Authority project and Common Language 22 History 4 Commentary: The Minister of Social Affairs, Henriette Kjær 22 The MedCom steering group 6 The LÆ form project 23 Commentary: The Minister of the Interior and Commentary: The Chairman of the National Health, Lars Løkke Rasmussen 7 Association of Local Authorities, Perspective: MedCom certifies communication 8 Ejgil W. Rasmussen 24 Perspective: The IT Lighthouse’s local authority- The Internet strategy 9 medical practice communication 24 The infrastructure project 9 The hospitals and Commentary: The Chairman of the Association of healthcare communication 25 County Councils, Kristian Ebbensgaard 12 Perspective: The Internet strategy and the From -

The Parliamentary Electoral System in Denmark

The Parliamentary Electoral System in Denmark GUIDE TO THE DANISH ELECTORAL SYSTEM 00 Contents 1 Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................................................................................................3 1. The Parliamentary Electoral System in Denmark ..................................................................................................4 1.1. Electoral Districts and Local Distribution of Seats ......................................................................................................4 1.2. The Electoral System Step by Step ..................................................................................................................................6 1.2.1. Step One: Allocating Constituency Seats ......................................................................................................................6 1.2.2. Step Two: Determining of Passing the Threshold .......................................................................................................7 1.2.3. Step Three: Allocating Compensatory Seats to Parties ...........................................................................................7 1.2.4. Step Four: Allocating Compensatory Seats to Provinces .........................................................................................8 1.2.5. Step Five: Allocating Compensatory Seats to Constituencies ...............................................................................8 -

Rules for Companies Operating in Denmark

Juni 2018 Rules for companies operating in Denmark Foreign companies and posted workers performing work in Denmark must be familiar with Danish labour market regulations and must comply with these rules. In this leaflet you can read more about working conditions in Denmark, RUT, health and safety requirements and tax rules. You can read more on WorkplaceDenmark.dk. 2 Rules and rights when working in Denmark Contents Register of Foreign Service Providers Register of Foreign Service Providers (RUT) 4 Working conditions in Denmark The right to organise 5 Wages and salaries 5 Working hours 6 Holiday rules 6 Prohibition against discrimination 9 Equal opportunities and equal pay 9 VAT and tax VAT and tax 10 Danish working environment rules The Danish Working Environment Authority 12 Requirements for health and safety collaboration 12 Alternating workplaces 13 Workplace risk assessments 13 Industrial injuries Working for longer periods in Denmark 15 List of insurance companies in Denmark 15 Reporting industrial injuries 16 Health and safety in the building and construction sector Advice for ensuring safe and healthy building sites 19 Handbook on health and safety in the building and construction sector 19 Rules and rights when working in Denmark 3 Register of Foreign Service Providers As a foreign employer temporarily pro- pany has been registered, you will viding services in Denmark, you must receive a receipt containing your RUT notify the Register of Foreign Service number. You will need to use this when Providers (RUT) electronically about you contact the Danish authorities. your company and services. This also applies to self-employed contractors If you perform work in building and without employees. -

No. 541 BELGIUM, CANADA, DENMARK, FRANCE, ICELAND

No. 541 BELGIUM, CANADA, DENMARK, FRANCE, ICELAND, ITALY, LUXEMBOURG, NETHERLANDS, NORWAY, PORTUGAL, UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA North Atlantic Treaty. Signed at Washington, on 4 April 1949 English and French official texts communicated by the Permanent Representa tive of the United States of America at the seat of the United Nations. The registration took place on 7 September 1949. BELGIQUE, CANADA, DANEMARK, FRANCE, ISLANDE, ITALIE, LUXEMBOURG, PAYS-BAS, NORVEGE, PORTUGAL, ROYAUME-UNI DE GRANDE-BRETAGNE ET D©IRLANDE DU NORD et ETATS-UNIS D©AMERIQUE Trait de l©Atlantique Nord. Sign Washington, le 4 avril 1949 Textes officiels anglais et français communiqués par le représentant permanent des Etats-Unis d'Amérique au siège de l'Organisation des Nations Unies. L'enregistrement a eu lieu le 7 septembre 1949. 244 United Nations — Treaty Series_________1949 No. 541. NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY1. SIGNED AT WASH INGTON, ON 4 APRIL 1949 The Parties to this Treaty reaffirm their faith in the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and their desire to live in peace with all peoples and all governments. They are determined to safeguard the freedom, common heritage and civilization of their peoples, founded on the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law. They seek to promote stability and well-being in the North Atlantic area. They are resolved to unite their efforts for collective defense and for the preservation of peace and security. They therefore agree to this North Atlantic Treaty: Article 1 The Parties undertake, as set forth in the Charter of the United Nations, to settle any international disputes in which they may be involved by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security, and justice, are not endangered, and to refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force in any manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations. -

Choosing an Investment Vehicle European Real Estate Fund Regimes

Choosing an investment vehicle European Real Estate Fund Regimes May 2019 www.pwc.com/realestate This content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors. Introduction This booklet aims to provide an overview of the most common European collective investment vehicles (CIVs) suitable for investment in real estate, including their legal form, as well as their regulatory and tax position. The AIFM Directive entered into force on Many countries offer attractive tax facilities, 22 July 2013 and has been implemented by including tax exemptions, to their local real EU Member States, which had to consider estate CIVs. In many countries, these tax both regulatory matters and changes to facilities are not available to real estate CIVs Uwe Stoschek fund and investor taxation. This has resulted investing from a different jurisdiction. Therefore, in significant changes in the European real there are still important steps to take until there Partner, estate fund landscape. AIFMD has forced is a level playing field for real estate CIVs also Global Real Estate Tax fund managers and investors to change from a tax perspective. Our country specialists Leader their approach and look not only at national mentioned in this publication will be very happy PwC Germany rules, but also at EU rules and guidelines. to help you by providing further information on At the same time, the new passports for any of the fund vehicles described. +49 30 2636-5286 professional investor funds provide new +49 160 5820641 options. Managers must consider where they [email protected] apply for authorisation to obtain the licence, paying close attention to legal and tax aspects, as well as available business infrastructure and personal resources. -

The Øresund Fixed Link (Denmark – Sweden)

Draft for Consultation The Øresund Fixed Link (Denmark – Sweden) Source: Ramboll Location Copenhagen (Denmark) – Malmö (Sweden) Northern Europe, Øresund region, Sector Transportation Procuring Authorities Øresundsbro Konsortiet Project Company Øresundsbro Konsortiet Project Company Obligations Design, Build, Finance, Maintain, Own and Operate (DBFMOO) Financial Closure Year - Capital Value USD 3.7 billion (DKK 30.1 billion) 2000 prices Start of Operations 2000 Contract Period (years) - Key Facts Government financed, 100% user funded 1/11 Draft for Consultation Project highlights The Øresund Fixed Link (the Link) is a fixed combined bridge and tunnel link across the Øresund Sound (the Sound) between Denmark and Sweden. It comprises: ● The Øresund tunnel between Amager – at Kastrup, south of Copenhagen, and the artificial island Peberholm. 1 ● The Øresund Bridge, a combined girder and cable-stayed bridge between Peberholm and Lernacken – south of Malmö, in Skåne. The Link is composed of a motorway and a dual 1. The Øresund Fixed Link rail track. The total length is 15.9 km. (Source: Øresundsbro Konsortiet) The Øresund Fixed Link is owned and operated by Øresundsbro Konsortiet, which is jointly owned by state-owned enterprises A/S Øresund and Svensk-danska Broförbindelsen (SVEDAB) AB. The latter is owned by the Swedish Government, while A/S Øresund is 100 per cent owned by Sund & Bælt, which is owned by the Danish state (see also Figure Error! Reference source not found.). The total cost of the Link, including the motorway and rail connection on land, was calculated at DKK 30.1 billion in 2000 (circa USD 3.7 billion, 2000 prices). The realisation of the project received financial support of DKK 780 million (USD 96.6 million) from the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) funding.