INTRODUCTION Mediating Publics and Anthropology R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Media Anthropology to the Anthropology of Mediation

4.4.3 From Media Anthropology to the Anthropology of Mediation Dominic Boyer When one speaks of media and mediation in and Coman 2005), professorial chairs and research social-cultural anthropology today one is usually and training centres (e.g., the USC Center for referring to communication and culture. This is to Visual Anthropology, the Program in Culture and say, when anthropologists use the term ‘media’, Media at NYU, the Programme in the Anthropology they tend to remain within a largely popular of Media at SOAS, the Granada Centre for Visual semantics, taking ‘media’ to mean communica- Anthropology at Manchester University, the MSc tional media and, more specifically, communica- in Digital Anthropology at University College tional media practices, technologies and London, among others), and research networks institutions, especially print (Peterson 2001; (e.g., EASA’s media anthropology listserv: http:// Hannerz 2004), film (Ginsburg 1991; Taylor www.media-anthropology.net). 1994), photography (Ruby 1981; Pinney 1997), Yet, as my fellow practitioners of media anthro- video (Turner 1992, 1995), television (Michaels pology would likely agree, it is very difficult to 1986; Wilk 1993; Abu-Lughod 2004), radio separate the operation of communicational media (Spitulnik 2000; Hernandez-Reguant 2006; cleanly from broader social-political processes of Kunreuther 2006; Fisher 2009), telephony (Rafael circulation, exchange, imagination and knowing. 2003; Horst and Miller 2006), and the Internet This suggests a productive tension within media (Boellstorff 2008; Coleman and Golub 2008; anthropology between its common research foci Kelty 2008), among others. These are the core (which are most often technological or representa- areas of attention in the rapidly expanding sub- tional in their basis) and what we might gloss as field of anthropological scholarship often known processes of social mediation: i.e. -

Sound Recordings

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title Sound Recordings Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/56f745rc ISBN 9780470657225 Author Novak, DE Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Trim Size: 170mm x 244mm Callan wbiea1336.tex V1 - 09/16/2017 3:01 P.M. Page 1 ❦ Sound Recordings DAVID NOVAK University of California, Santa Barbara, United States Sound recordings have played an important role in anthropological research, both as tools of feldwork and data collection and as objects and contexts of ethnographic work on music, language, and cultural mediations of technology and environment. Te pro- cess of sound recording introduced new techniques and materials that revolutionized anthropological studies of language, music, and culture, while, as objects of techno- logical production and consumption, their media circulations have been analyzed as intrinsic to modern cultural formation and global social imaginaries. Te emergence of anthropology as a scholarly discipline coincided with the develop- ment of mechanical technologies for the preservation and reproduction of sound, fol- lowing soon afer the invention of the Edison cylinder phonograph in 1877. Te phono- graph made it possible for early ethnographers to capture and analyze the sounds of speech and ritual performance in Native America, beginning with the Passamaquoddy and Zuni songs and stories recorded in 1890 on wax cylinders by Jesse Walter Fewkes, and soon afer by Frances Densmore and Alice Cunningham Fletcher. While oral histo- rians, linguists, and musicologists regularly used the phonograph to collect and analyze the texts of threatened languages and musics in a preservationist mode, they did not typically preserve sound recordings themselves; in stark contrast to the archival stan- ❦ dards that would emerge later, most of them destroyed or reused cylinders immediately ❦ afer having transcribed their contents. -

The Digital Turn: New Directions in Media Anthropology

The Digital Turn: New Directions in Media Anthropology Sahana Udupa (Ludwig Maximilian University Munich) Elisabetta Costa (University of Groningen) Philipp Budka (University of Vienna) Discussion Paper for the Follow-Up E-Seminar on the EASA Media Anthropology Network Panel “The Digital Turn” at the 15th European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) Biennial Conference, Stockholm, Sweden, 14-17 August 2018 16-30 October 2018 http://www.media-anthropology.net/ With the advent of digital media technologies, internet-based devices and services, mobile computing as well as software applications and digital platforms new opportunities and challenges have come to the forefront in the anthropological study of media. For media anthropology and related fields, such as digital and visual anthropology, it is of particular interest how people engage with digital media and technologies; how digital devices and tools are integrated and embedded in everyday life; and how they are entangled with different social practices and cultural processes. The digital turn in media anthropology signals the growing importance of digital media technologies in contemporary sociocultural, political and economic processes. This panel suggested that the digital turn could be seen a paradigm shift in the anthropological study of media, and foregrounded three important streams of exploration that might indicate new directions in the anthropology of media. More and more aspects of people’s everyday life and their lived experiences are mediated by digital technologies. Playing, learning, dating, loving, migrating, dying, as well as friendship, kinship, politics, and news production and consumption, have been affected by the diffusion of digital technologies. We often hear far-reaching statements about these transformations, such as euphoric pronouncements about digital media as a radical enabler of grassroots democracy. -

Anthropology of Media and Culture 70:368 Rutgers Fall 2016 3 Credits T-Th 5:35-6:55 HCK 119

Anthropology of Media and Culture 70:368 Rutgers Fall 2016 3 credits T-Th 5:35-6:55 HCK 119 Professor: Becky Schulthies, Ph.D. Office Hours: 3:45-5pm Tue-Thu or by appointment Office: 312 RAB Email: [email protected] COURSE OBJECTIVES: What do you think of when you hear the word “media”? What do you think should be included in the category? How do you think media works or should work? How might mediation work in places beyond your experience? Some argue that media are contested and significant factors in the exercise of power and identity. Others suggest that media impacts are more diffuse and uncertain. This seminar will explore the development of an anthropological approach to mass media studies by focusing on a few themes: media and socio-economic development; the socio-political lives of news; relationship ideologies and social media. We will explore historical and contemporary mediascapes and how anthropologists have theorized their significance and impact. Numerous pundits on all sides have much to say about media: they decry the bias or praise the objectivity of media sources; propound the positive potential effects of media influence for conflict resolution and public relations or lament the negative stereotyping and violence resulting from media impacts; condemn media as another form of authoritarian control, an extension of imperialism, or laud its contributions to globalization and economic development in the Global South. This course will lay the anthropological groundwork for theories approaching these perspectives, and discuss the relationships between media, culture, politics, and religion. Media anthropology emerged from critical engagements with ethnographic film, visual anthropology, the 1980s crisis of representation, and globalization theory. -

Media Anthropology: an Overview Mihai Coman University of Bucharest, Romania [email protected]

Media Anthropology: An Overview Mihai Coman University of Bucharest, Romania [email protected] ABSTRACT The meeting between cultural anthropology and mass media is, in fact, a meeting between an object of research and a scientific discipline. In such a situation, the discipline brings with it certain delineations, a number of investigating methods, and a group of relatively specific concepts and theories. In the case of media anthropology, the fact that various researchers do not assume that clear disciplinary identity (with roots in sociology, cultural studies, narratology, history, etc) yet use concepts specific to cultural anthropology, as well as research methods intimately related to this science (ethnographic methods), may appear as a random meeting, and a passing experience. Especially since the authorized representatives of cultural anthropology have treated these attempts with skepticism. On the other hand, border-crossing and interpreting mass media phenomena from a cultural anthropology perspective can also be understood as the beginning of delineating a new sub- discipline of cultural anthropology, or of communication studies, a sub-discipline that has as its research object a specific form of cultural creation - the mass media. Or as the first step in the creation of a new anthropological frame for the study of the global and mediated cultural phenomena. 2 “For many years mass media were seen as almost a taboo topic for anthropology” (Ginsburg et al, 2003:3). Faye Ginsburg’s formula states a truth and hides another. Indeed, anthropologists have not been interested in mass media, or have reduced it to a simple work tool for (what they thought it represented) an “accurate” recording of social facts, or to an accessory in the study of other social and cultural phenomena. -

Media Anthropology in a World of Modern States

Media anthropology in a world of states Dr John Postill bremer institut für kulturforschung (bik) University of Bremen Postbox 33 04 40 D-28334 Bremen Germany [email protected] Paper presented to the EASA Media Anthropology e-Seminar, 19-26 April 2005 http://www.media-anthropology.net Draft first chapter of forthcoming Media and Nation-Building: How the Iban Became Malaysian. Oxford and New York: Berghahn. Abstract This paper suggests that media anthropology should pay closer attention to the manifold nation-building uses of media technologies, especially in postcolonial and post-Soviet countries. Adopting an ethnological approach, it questions the present celebration of the creative appropriation of media forms, and argues that it is time to reintroduce diffusionist approaches that can complement the prevailing appropriationism. In the same ethnological vein, it also suggests that modern states are not imagined communities but rather the prime culture areas (Kulturkreise) or our era, and that modern media are indispensable in the making of these culture areas. 2 1 Introduction: media anthropology in a world of states The present world is a world of states, neither a world of tribes nor a world of empires, though the remnants of such forms are still present and occupy part of our thinking. Nicholas Tarling We live in a world of states. We have lived in such a world since the dismantling of the British and French empires after the Second World War. The remnants of both empires are still present, but the influence of Britain and France has waned as steadily as that of the United States, China, and other large states has grown. -

EASA Media Anthropology Network E-Seminar 22 October – 5 November 2008

EASA Media Anthropology Network E-Seminar 22 October – 5 November 2008 http://www.media-anthropology.net/ Dr. Eric Rothenbuhler (Texas A&M University) Media anthropology as a field of interdisciplinary contact ABSTRACT Media anthropology is a rapidly developing new field of interdisciplinary studies. With roots going back decades in both Communication and Anthropology, nevertheless this work has only recently coalesced under the label Media Anthropology and its contributing authors come into dialogue. In turn this has produced a moment of intellectual self-consciousness about the tasks of defining this field of study and debating its parameters. This essay argues that media anthropology is and would most profitably continue to be a field of contact between two disciplines, rather than generating a new disciplinary frame of its own. Often this contact is rudimentary, but productively so. Anthropologists and communication scholars approach Media Anthropology from different directions with different histories and for different purposes. It is not only natural, but productive, that they would make differing choices of concepts, methods, and interpretations. This is as it should be and attempts to discipline Media Anthropology will either fail or bleed the territory of its vitality. Sigurjón B Hafsteinsson sbh at hi.is Wed Oct 22 00:50:53 PDT 2008 Dear list, Today we start our 23rd e-seminar! We will discuss until Eric W. Rothenbuhler´s paper “Media Anthropology as a Field of Interdisciplinary Contact" until November 5. For those who still haven´t read Rothenbuhler´s paper there is still time. The paper is available at our website at http://www.media-anthropology.net/workingpapers.htm The discussant Ariel Heryanto will post his comments to the list late this evening (Wednesday) or tomorrow (Thursday). -

Notes for the Gebusi, 4Th Edition

Notes for The Gebusi, 4th edition INTRODUCTION How to appreciate cultural diversity while criticizing inequality and domination. These complementary themes and their historical relationship in anthropology are discussed in greater detail in Genealogies for the Present in Cultural Anthropology (Knauft 1996, pp. 48–57). The Gebusi in 1998 versus 1980–82. An extended scholarly description of Gebusi society in 1980–82 is Good Company and Violence: Sorcery and Social Action in a Lowland New Guinea Society (Knauft 1985a). A more detailed account of Gebusi changes in 1998 can be found in Exchanging the Past: A Rainforest World of Before and After (Knauft 2002a), and in a chapter on changes in Gebusi performance and body art (Knauft 2007b). The Nomad Station as a local place of influence and power. See the discussion in “How the World Turns Upside Down: Changing Geographies of Power and Spiritual Influence among the Gebusi” (Knauft 1998a—available on the author’s website). Becoming modern—a process that is both culturally diverse and global in scope. See the collected essays on this topic in Critically Modern (Knauft 2002c) and Knauft (2007b). A fascinating case study of a rural people who are becoming alternatively modern in Togo, West Africa, can be found in Charles Piot’s Remotely Global: Village Modernity in West Africa (1999). For an urban example that focuses on women in China, see Lisa Rofel’s monograph Other Modernities: Gendered Yearnings in China After Socialism (1999). The concept of being “otherwise modern” has also been criticized for implying an “equality” between modernity in different world areas. -

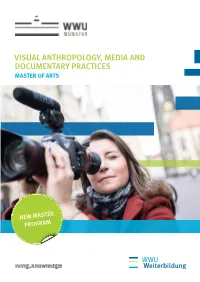

Visual Anthropology, Media and Documentary Practices Master of Arts

VISUAL ANTHROPOLOGY, MEDIA AND DOCUMENTARY PRACTICES MASTER OF ARTS NEW MASTER PROGRAM 2 WWU WEITER BILDUNG 03 INDEX OBJECTIVES OF THE MASTER PROGRAM 04 STRUCTURE AND PROGRAM OUTLINE 05 STUDY ORGANIZATION 10 ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS AND APPLICATION 11 MANAGEMENT AND LECTURERS 11 YoUR STAY IN MÜNSTER 12 CoNTACT AND IMPRINT 14 04 OBJECTIVES OF THE MastER PROGRAM OBJECTIVES OF THE MASTER PROGRAM In today’s globalized world, where media representations This program is for students with a background in the social shape social and political spheres, a critical understanding sciences and humanities, especially those in cultural, media of media and (audio-) visual culture is crucial. Media studies, and communication studies. Applications are welcome from rooted in social anthropology, offers an in-depth approach both Germany and abroad. to analyzing the complex connections between media, culture and society. The Master Program trains students in theory and practice in the areas of visual anthropology, the documentary arts (film/photography/installation), media culture and media anthropology. Conceptual and practical knowledge within these areas can be applied in academia, the arts, and culture and media industries, as well as to social, applied, or educational media projects. Students study the theoretical and practical foundations of visual anthropology, they gain experience in film production, project development, and (audio-) visual installation. Ultimately, they acquire the necessary skills for producing their own research projects and media outputs. STRUCTURE AND PROGRAM OUTLINE 05 STRUCTURE AND PROGRAM OUTLINE > Structure The Master Program was designed with working professio- Students have the possibility to complete the program after nals in mind. The in-house classes will be offered as block 5 semesters (two and a half years). -

Digital Anthropology

Digital Anthropology Digital Anthropology Edited by Heather A. Horst and Daniel Miller London • New York English edition First published in 2012 by Berg Editorial offi ces: 50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP, UK 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA © Heather A. Horst & Daniel Miller 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of Berg. Berg is an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 0 85785 291 5 (Cloth) 978 0 85785 290 8 (Paper) e-ISBN 978 0 85785 292 2 (institutional) 978 0 85785 293 9 (individual) www.bergpublishers.com Contents Notes on Contributors vii PART I. INTRODUCTION 1. The Digital and the Human: A Prospectus for Digital Anthropology 3 Daniel Miller and Heather A. Horst PART II. POSITIONING DIGITAL ANTHROPOLOGY 2. Rethinking Digital Anthropology 39 Tom Boellstorff 3. New Media Technologies in Everyday Life 61 Heather A. Horst 4. Geomedia: The Reassertion of Space within Digital Culture 80 Lane DeNicola PART III. SOCIALIZING DIGITAL ANTHROPOLOGY 5. Disability in the Digital Age 101 Faye Ginsburg 6. Approaches to Personal Communication 127 Stefana Broadbent 7. Social Networking Sites 146 Daniel Miller PART IV. POLITICIZING DIGITAL ANTHROPOLOGY 8. Digital Politics and Political Engagement 165 John Postill – v – vi • Contents 9. Free Software and the Politics of Sharing 185 Jelena Karanović 10. -

The Anthropology of Media and the Question of Ethnic and Religious Pluralism

PATRICK EISENLOHR The anthropology of media and the question of ethnic and religious pluralism This essay discusses anthropological approaches to the study of media interacting with contexts of ethnic and religious diversity. The main argument is that not only issues of access to and exclusion from public spheres are relevant for an understanding of media and pluralism. Background assumptions and ideologies about media technologies and their functioning also require more comparative analysis, as they impact public spheres and claims to authority and authenticity that ultimately produce and shape scenarios of ethnic and religious diversity. This additional dimension of diversity in the question of media and ethnic and religious pluralism is particularly apparent in crises of political and religious mediation. The latter often result in desires to bypass established forms of political and religious mediation that are in turn often projected on new media technologies. Key words media, pluralism, religion, ethnicity, public sphere For quite some time anthropologists have asked how media influence ethnic and religious belonging, the formation of ethnic and religious networks and communities, and how, more generally, uses of media technology shape the relationships between people of different ethnic and religious backgrounds. Do media not profoundly shape our impressions of the ethnic and religious other? After all, trends of intensified globalisation in the last three decades appear to have brought about a global media- sustained imaginary in which such representations are produced and circulated. And can media not also appear as fearful agents of separation, purism, and ethnic and religious antagonism, as most chillingly exemplified in the 1994 radio broadcasts by Radio Tel´ evision´ Libre des Mille Collines that called on Rwandans to engage in genocidal murder of their neighbours? But the subject of media and ethnic and religious diversity has of course a fairly long genealogy. -

Beyond Normative Dewesternization: Examining Media Culture from the Vantage Point of the Global South

Wendy Willems Beyond normative dewesternization: examining media culture from the vantage point of the Global South Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Willems, Wendy (2014) Beyond normative dewesternization: examining media culture from the vantage point of the Global South. The Global South, 8 (1). pp. 7-23. ISSN 1932-864 © 2014 Indiana University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/61882/ Available in LSE Research Online: May 2015 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Beyond normative dewesternization: examining media culture from the vantage point of the Global South Wendy Willems Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, United Kingdom Department of Media Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa Forthcoming in: The Global South, http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublication?journalCode=globalsouth ABSTRACT This article examines five dominant conceptualizations of “the Global South” in the field of media and communication studies, and more specifically in the subfields of (1) comparative media studies, (2) international communication or global media studies, and (3) development communication.