Cubagua's Pearl-Oyster Beds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 4.1. the Political Subdivisions of the Antilles, Size of the Islands, and Representative Climatic Data

Table 4.1. The political subdivisions of the Antilles, size of the islands, and representative climatic data. sl= sea level. Compiled from various sources. Area (km2) Climatic data Site/elev. (m) MAT(oC) MAP (mm/yr) Greater Antilles (total area 207,435 km2) Cuba 110,860 Nueva Gerona 65 25.3 1793 Pinar del Rio 26 1610 Havana 26 25.1 1211 Cienguegos 32 24.6 98.3 Camajuani 110 22.8 1402 Camagữey 114 25.2 1424 Santiago de Cuba 38 26.1 1089 Hispaniola 76,480 Haiti 27,750 Bayeux 12 24.7 2075 Les Cayes 7 25.7 2042 Ganthier 76 26.2 792 Port-au-Prince 41 26.6 1313 Dominican Republic 48,730 Pico Duarte 2960 - (est. 12) 1663 Puerto Plata 13 25.5 1663 Sanchez 16 25.2 1963 Ciudad Trujillo 19 25.5 1417 Jamaica 10,991 S. Negril Point 10 25.7 1397 Kingston 8 26.1 830 Morant Point sl 26.5 1590 Hill Gardens 1640 16.7 2367 Puerto Rico 9104 Comeiro Falls 160 24.7 2011 Humacao 32 22.3 2125 Mayagữez 6 25 2054 Ponce 26 25.8 909 San Juan 32 25.6 1595 Cayman Islands 264 Lesser Antilles (total area 13,012 km 2) Antigua and Barbuda 81 Antigua and Barbada 441 Aruba 193 Barbados 440 Bridgetown sl 27 1278 Bonaire 288 British Virgin Islands 133 Curaçao 444 Dominica 790 26.1 1979 Grenada 345 24.0 4165 Guadeloupe 1702 21.3 2630 Martinique 1095 23.2 5273 Montesarrat 84 Saba 13 Saint Barthelemy 21 Saint Kitts and Nevis 306 Saint Lucia 613 Saint Marin 3453 Saint Vicent and the Grenadines 389 Sint Eustaius 21 Sint Maarten 34 Trinidad and Tobago 5131 + 300 Trinidad Port-of-Spain 28 26.6 1384 Piarco 11 26 185 Tobago Crown Point 3 26.6 1463 U.S. -

Early Colonial History Four of Seven

Early Colonial History Four of Seven Marianas History Conference Early Colonial History Guampedia.com This publication was produced by the Guampedia Foundation ⓒ2012 Guampedia Foundation, Inc. UOG Station Mangilao, Guam 96923 www.guampedia.com Table of Contents Early Colonial History Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas ...................................................................................................1 By Rebecca Hofmann “Casa Real”: A Lost Church On Guam* .................................................13 By Andrea Jalandoni Magellan and San Vitores: Heroes or Madmen? ....................................25 By Donald Shuster, PhD Traditional Chamorro Farming Innovations during the Spanish and Philippine Contact Period on Northern Guam* ....................................31 By Boyd Dixon and Richard Schaefer and Todd McCurdy Islands in the Stream of Empire: Spain’s ‘Reformed’ Imperial Policy and the First Proposals to Colonize the Mariana Islands, 1565-1569 ....41 By Frank Quimby José de Quiroga y Losada: Conquest of the Marianas ...........................63 By Nicholas Goetzfridt, PhD. 19th Century Society in Agaña: Don Francisco Tudela, 1805-1856, Sargento Mayor of the Mariana Islands’ Garrison, 1841-1847, Retired on Guam, 1848-1856 ...............................................................................83 By Omaira Brunal-Perry Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas By Rebecca Hofmann Research fellow in the project: 'Climates of Migration: -

Desarrollo Embrionario Y Larval De Lytechinus Variegatus (Echinoidea: Toxopneustidae) En Condiciones De Laboratorio En La Isla De Margarita-Venezuela

Desarrollo embrionario y larval de Lytechinus variegatus (Echinoidea: Toxopneustidae) en condiciones de laboratorio en la Isla de Margarita-Venezuela Olga Gómez M.1 & Alfredo Gómez G.2 1 Instituto de Investigaciones Científicas de la Universidad de Oriente, Boca del Río - Nueva Esparta, Venezuela; Telefax: 0295 2913150; [email protected] 2 Museo Marino de Margarita; Telefax: 0295 2913132; [email protected] Recibido 14-VI-2004. Corregido 09-XII-2004. Aceptado 17-V-2005. Abstract: Embrionary and larval development of Lytechinus variegatus (Echinoidea: Toxopneustidae) in laboratory conditions at Isla de Margarita-Venezuela. The sea urchin Lytechinus variegatus is a promissory species for aquaculture activities in tropical countries. In Venezuela, this species has some economical impor- tance but their embryonic and larval development had not been studied. We collected specimens from seagrass beds in Margarita Island (Venezuela) and kept them in the laboratory, where they spawned naturally. With filtered sea water (temperature 28ºC, salinity 37 psu) and moderate aeration, the eggs and sperm were mixed (relation 1:100) and reached a 90% fertilization rate. The fertilization envelope was observed after two minutes, the first cellular division after 45 minutes and the prism larval stage after 13 hours. The echinopluteus larval stage was reached after 17 hours and metamorphosis after 18 days of planktonic life, when the larvae start their benthic phase. Rev. Biol. Trop. 53(Suppl. 3): 313-318. Epub 2006 Jan 30. Key words: Sea urchins, Lytechinus variegatus, larvae, larval development, culture, echinoid, echinoderms. Los erizos tienen gran importancia econó- ha ocurrido en otros países. La especie tiene mica porque sus gónadas se consideran exqui- un rápido crecimiento, madura sus gónadas siteces y son altamente apreciadas en algunos en corto periodo de tiempo y por la facilidad países europeos, en América del Sur y Asia. -

C:\Users\Usuario\Desktop\TFE

Título Superior de Música. Especialidad Interpretación (Violonchelo) Trabajo Fin de Estudios PROPUESTA INTERPRETATIVA DE LA OBRA SUITE FOR CELLO AND PIANO DE ALDEMARO ROMERO ALUMNO: MARIO HIDALGO BERROCAL MODALIDAD A: Trabajo teórico-práctico de carácter profesional TUTORA: Mª NATIVIDAD ÁLVAREZ-OSSORIO TORRES CURSO 2017-2018 Jaén, Junio 2018 Título Superior de Música. Especialidad Interpretación (Violonchelo) Trabajo Fin de Estudios PROPUESTA INTERPRETATIVA DE LA OBRA SUITE FOR CELLO AND PIANO DE ALDEMARO ROMERO ALUMNO: MARIO HIDALGO BERROCAL MODALIDAD A: Trabajo teórico-práctico de carácter profesional TUTORA: Mª NATIVIDAD ÁLVAREZ-OSSORIO TORRES CURSO 2017-2018 Jaén, Junio 2018 Conservatorio Superior de Música de Jaén. Trabajo Fin de Estudios MARIO HIDALGO BERROCAL ÍNDICE GENERAL ÍNDICE DE TABLAS ................................................................................................ II ÍNDICE DE IMÁGENES ........................................................................................... II RESUMEN Y PALABRAS CLAVE .............................................................................. 1 ABSTRACT AND KEYWORDS ................................................................................. 2 1. INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................................................................... 3 2. ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN ............................................................................ 4 2.1. Objetivos ......................................................................................................... -

26. the Pearl Fishery of Venezuela

THE PEARL FISHERY OF VENEZUELA Marine Biological Lafi'ir-toiy X.I B K. A. R TT JUN 2 41950 WOODS HOLE, MASS. SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC REPORT: FISHERIES No. 26 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Explanatory Ifote The series embodies restilts of investigations, usiially of restricted scope, intended to aid or direct management or utilization practices and as guides for adminl- str.itive or legislative action. It is issued in limited auantities for the official use of Federal, State or cooperating agencies and in processed form for econony and to avoid del.oy in publication. Washington, 0. C. May 1950 United States Department of the Interior Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary Pish and Wildlife Service Albert M. Day, Director Special Scientific Report - Fisheries Ho. 26 THE PEARL FISHERY OF VENEZUELA Paul S. Galtsoff Fishery Research Biologist COMTEHTS Page Introduction 2 Brief history of the pearl fishery 2 Present condition of pearl fishery »•.. ••*............ 7 1. Location of pearl oyster banks 7 2. Method of fishing 10 3« Season of fishing ............ 10 U, Shucking of oysters ^... 11 5. Division of the proceeds ,. 12 6. Selling of pearls ..... ........... 13 7. Market for pearls , 1^ 8. Economic importance of pearl fishery I7 Biology fud conservation of pearl oyster I9 Sugf^ested plan of biological sttidies 20 Bibliography 23 lETEODUCTION At the invitation of the Venezuelan Governnent the euthor had an opportimity to visit in March-April I9U8 the principal pecxl oyster gro-unds in the vicinity of Margarita Island. Ihjring this trip it was possible to inspect in detail the methods of fishing, to observe the a-onraisal and sale of pearls in Porlamar, and to obtain an understanding of the ver:-' efficient system of government management of the fishery by the Ministerio de Agricul- tura y Crfa. -

Redalyc.Dinámica Del Espacio Geográfico Margariteño En El Siglo

Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Sistema de Información Científica Antonio R. Boadas Dinámica del espacio geográfico margariteño en el siglo XX. (Trabajo Preliminar) Terra Nueva Etapa, vol. XXIII, núm. 33, 2007, pp. 99-126, Universidad Central de Venezuela Venezuela Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=72103305 Terra Nueva Etapa, ISSN (Versión impresa): 1012-7089 [email protected] Universidad Central de Venezuela Venezuela ¿Cómo citar? Fascículo completo Más información del artículo Página de la revista www.redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Dinámica del espacio geográfico margariteño en el siglo XX. (Trabajo preliminar) 99 Terra. Vol. XXIII, No. 33, 2007, pp. 99-126 DINÁMICA DEL ESPACIO GEOGRÁFICO MARGARITEÑO EN EL SIGLO XX* (Trabajo Preliminar) Margarita Island’s Geographical Space Dynamics in the Twentieth Century (Preliminary Work) Antonio R. Boadas RESUMEN: En el siglo XX se produjeron grandes transformaciones en el espacio geográfico margariteño. En este trabajo, previo a un análisis posterior, se señalan factores y agentes de acontecimientos que han concurrido y favorecido tales transformaciones. Entre otros se anotan movimientos demográficos de entrada y salida de población, dotación de infraestructuras y medios para transporte, comercio y servicios, y valorización de la isla como destino turístico y recreacional. Estos acontecimientos y las transformaciones generadas ocurrieron mayoritariamente en la segunda mitad del siglo, y se tradujeron en cambios en la utilización del territorio, que son evidentes en las expansiones urbanas, la aparición de nuevos espacios urbanizados y la conformación de zonas de aprovechamiento turístico y comercial. -

ANALISIS 1Ecrono-SEDIMENTARIO DE LA FORMACION PAMPATAR (EOCENO MEDIO), ISLA DE MARGARITA, VENEZUELA 1

Asoc. Paleont. Arg., PubJ. Espec. N° 3 ISSN 0328-347X PALEOGENO DE AMERICA DEL SUR: 27-33. Buenos Aires, 1995. IU S UNES O I 301 ANALISIS 1ECroNO-SEDIMENTARIO DE LA FORMACION PAMPATAR (EOCENO MEDIO), ISLA DE MARGARITA, VENEZUELA 1 Jhonny E. CASAS B. 2, Joselys MORENO V. 3 Y Franklin YORIS V. 4 ABSTRACf: TECTONIC AND SED¡MENTARY ANALYS¡S OF THE PAMPATAR FORMATlON (MIDDLE EOCENE), MAR- GARITA ¡SLAND, VENEZUELA. The Pampatar Fonnation (Eocene) of Margarita Island, Venezuela, consists mainly of inter- bedded sandstones and shales, with some conglomerates. These sediments are interpreted as turbidites deposited in submarine canyons and fans. The conglomerates represent canyon and inner-fan-channel deposits. The rest of the succession represents the entire range of fan environments, from inner to outer fan. Triangular diagrams of sandstone composition (100 samples) elucidate the tectonic setting. Most samples plot in the "recycled orogenic" field of the Q-F-L triangle, while the Qm-F-Lt diagram shows a wider dispersion, including "transitional recycled", "rnixed zone", and "magmatic are". This association is interpreted in tenns of uplift and erosion of a subduction-accretion complex, which supplied most of the sediments to the Pampatar Fonnation (recycled orogen component), with an additional, minor contributions from a dissected and transitional magmatic are, KEy WORDS:Margarita Island, Pampatar Fonnation, Eocene, Turbidites, Sedimentary petrography, Triangular diagrams. PALABRASCLAVE: Isla de Margarita, Formación Parnpatar, Eoceno, Turbiditas, Petrografía sedimentaria, Diagramas trian- gulares. INTRODUCCION TRABAJOS PREVIOS El objetivo principal de esta investigación es rela- Rutten (1940) publica el primer trabajo científico cionar la composición de las areniscas de la Formación referente a la geología de la isla de Margarita, donde Pampatar con su ambiente de sedimentación y ubicación discute brevemente sus rocas sedimentarias atribuyén- geotectónica dentro del cuadro evolutivo del margen sur dolas al Eoceno, basado en la presencia de orbitoides. -

Aldemaro Romero Archive (ASM0038)

University of Miami Special Collections Finding Aid - Aldemaro Romero Archive (ASM0038) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: May 21, 2018 Language of description: English University of Miami Special Collections 1300 Memorial Drive Coral Gables FL United States 33146 Telephone: (305) 284-3247 Fax: (305) 284-4027 Email: [email protected] https://library.miami.edu/specialcollections/ https://atom.library.miami.edu/index.php/asm0038 Aldemaro Romero Archive Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Series descriptions .......................................................................................................................................... -

A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2021 The Past as "Ahead": A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism Gabby Lupola Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses Part of the Asian American Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Micronesian Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Oral History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lupola, Gabby, "The Past as "Ahead": A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism" (2021). Pomona Senior Theses. 246. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/246 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Past as “Ahead”: A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism Gabrielle Lynn Lupola A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History at Pomona College. 23 April 2021 1 Table of Contents Images ………………………………………………………………….…………………2 Acknowledgments ……………………..……………………………………….…………3 Land Acknowledgment……………………………………….…………………………...5 Introduction: Conceptualizations of the Past …………………………….……………….7 Chapter 1: Embodied Sociopolitical Sovereignty on Pre-War Guam ……..……………22 -

THE MARINE COMMUNITIES of MARGARITA ISLAND, VENEZUELA Gilberta RODRIGUEZ Fundaci6n Venezolana Para El a Vance De La Ciencia Caracas, 'Venezuela

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE OF THE GULF AND CARIBBEAN VOLUME 9 1959 NUMBER 3 THE MARINE COMMUNITIES OF MARGARITA ISLAND, VENEZUELA GILBERTa RODRIGUEZ Fundaci6n Venezolana para el A vance de la Ciencia Caracas, 'Venezuela ABSTRACT The communities of rocky, sandy and muddy shores are analyzed and the dominant species are recorded. The effect of some physical factors as exposure to wave action is correlated with the composition of the most conspicuous communities. The applicability of Stephenson's general scheme of zonation is discussed. From the results of this analysis an attempt is made to characterize and delimit the biogeographical province of the West Indies. At the end, a summary of the most common forms of marine plants and invertebrates of the area is given. INTRODUCTION Margarita is the largest of the islands in the Caribbean Sea off the north coast of Venezuela that are actually a part of the east-west trending Caribbean or Coast Range. It lies 30 kilometers north of the mainland in 11ON lat. and 64 oW long. It is composed of two mountain peaks joined together by two sand spits, between which is a large lagoon, Laguna de Restinga, open to the sea. The mountains average 800 meters high. The area to the east of Laguna Restinga, which al- most separates the two parts of the island, is nearly twice as large as the western part, which is locally called Macanao. The total area of Margarita is 1,150 square kilometers, its greatest length being 75 kilometers (Fig. 1). Southward, between Margarita and the mainland, there are two small islands, Cache and Cubagua. -

OVERDUE FINES: 25¢ Por Day Per Item RETURNING LIBRARY MATERIALS: P'iace in Book Return to Remove Chars

OVERDUE FINES: 25¢ por day per Item RETURNING LIBRARY MATERIALS: P'Iace in book return to remove chars. from circuhtion recon © Copyright by JACQUELINE KORONA TEARE 1980 THE PACIFIC DAILY NEWS: THE SMALL TOWN NEWSPAPER COVERING A VAST FRONTIER By Jacqueline Korona Teare A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS School of Journalism 1980 ABSTRACT THE PACIFIC DAILY NEWS: THE SMALL TOWN NEWSPAPER COVERING A VAST FRONTIER 3y Jacqueline Korona Teare Three thousand miles west of Hawaii, the tips of volcanic mountains poke through the ocean surface to form the le-square- mile island of Guam. Residents of this island and surrounding island groups are isolated from the rest of the world by distance, time and, for some, by relatively primitive means of communication. Until recently, the only non-military, English-language daily news- paper serving this three million-square-mile section of the world was the Pacific Daily News, one of the 82 publications of the Rochester, New York-based Gannett Co., Inc. This study will trace the history of journalism on Guam, particularly the Pacific Daily News. It will show that the Navy established the daily Navy News during reconstruction efforts follow- ing World War II. That newspaper was sold in l950 to Guamanian civilian Joseph Flores, who sold the newspaper in 1969 to Hawaiian entrepreneur Chinn Ho and his partner. The following year, they sold the newspaper now called the Pacific Daily News, along with their other holdings, to Gannett. Jacqueline Korona Teare This study will also examine the role of the Pacific Daily Ngw§_in its unique community and attempt to assess how the newspaper might better serve its multi-lingual and multi-cultural readership in Guam and throughout Micronesia. -

Confluence Saxophone Quartet

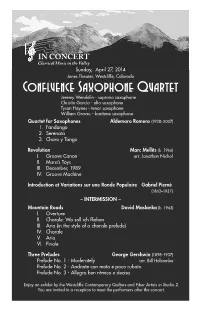

IN CONCERT Classical Music in the Valley Sunday, April 27, 2014 Jones Theater, Westcliffe, Colorado Confluence Saxophone Quartet Jeremy Wendelin - soprano saxophone Christin Garcia - alto saxophone Tyson Haynes - tenor saxophone William Graves - baritone saxophone Quartet for Saxophones Aldemaro Romero (1928–2007) 1. Fandango 2. Serenata 3. Choro y Tango Revolution Marc Mellits (b. 1966) I. Groove Canon arr. Jonathan Nichol II. Mara’s Toys III. December, 1989 IV. Groove Machine Introduction et Variations sur une Ronde Populaire Gabriel Pierné (1863–1937) – INTERMISSION – Mountain Roads David Maslanka (b. 1943) I. Overture II. Chorale: Wo soll ich fliehen III. Aria (in the style of a chorale prelude) IV. Chorale V. Aria VI. Finale Three Preludes George Gershwin (1898–1937) Prelude No. 1 - Moderately arr. Bill Holcombe Prelude No. 2 - Andante con moto e poco rubato Prelude No. 3 - Allegro ben ritmico e deciso Enjoy an exhibit by the Westcliffe Contemporary Quilters and Fiber Artists in Studio 2. You are invited to a reception to meet the performers after the concert. PROGRAM NOTES by David Niemeyer You may not be familiar with the name Aldemaro Romero, but you have probably heard his work many times over several decades. He worked with non-classical musicians including Dean Martin, Jerry Lee Lewis, Stan Kenton, and Tito Puente. In addition, Romero was a classical musician who was a guest conductor for the London Symphony Orchestra, the English Chamber Orchestra, and the Royal Phil- harmonic Orchestra, and he founded the Caracas Philharmonic Orchestra. As a composer, Romero stuck to his Venezuelan roots, as evidenced by the Quartet for Saxophones.