Could Human Coronavirus OC43 Have Co-Evolved with Early Humans?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

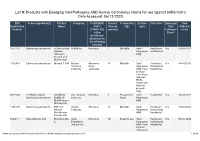

List N: Products with Emerging Viral Pathogens and Human Coronavirus Claims for Use Against SARS-Cov-2 Date Accessed: 06/12/2020

List N: Products with Emerging Viral Pathogens AND Human Coronavirus claims for use against SARS-CoV-2 Date Accessed: 06/12/2020 EPA Active Ingredient(s) Product Company To kill SARS- Contact Formulation Surface Use Sites Emerging Date Registration Name CoV-2 Time (in Type Types Viral Added to Number (COVID-19), minutes) Pathogen List N follow Claim? disinfection directions for the following virus(es) 1677-202 Quaternary ammonium 66 Heavy Duty Ecolab Inc Norovirus 2 Dilutable Hard Healthcare; Yes 06/04/2020 Alkaline Nonporous Institutional Bathroom (HN) Cleaner and Disinfectant 10324-81 Quaternary ammonium Maquat 7.5-M Mason Norovirus; 10 Dilutable Hard Healthcare; Yes 06/04/2020 Chemical Feline Nonporous Institutional; Company calicivirus (HN); Food Residential Contact Post-Rinse Required (FCR); Porous (P) (laundry presoak only) 4822-548 Triethylene glycol; Scrubbing S.C. Johnson Rotavirus 5 Pressurized Hard Residential Yes 06/04/2020 Quaternary ammonium Bubbles® & Son Inc liquid Nonporous Multi-Purpose (HN) Disinfectant 1839-167 Quaternary ammonium BTC 885 Stepan Rotavirus 10 Dilutable Hard Healthcare; Yes 05/28/2020 Neutral Company Nonporous Institutional; Disinfectant (HN) Residential Cleaner-256 93908-1 Hypochlorous acid Envirolyte O & Aqua Norovirus 10 Ready-to-use Hard Healthcare; Yes 05/28/2020 G Engineered Nonporous Institutional; Solution Inc (HN); Food Residential Contact Post-Rinse www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2 1 of 66 EPA Active Ingredient(s) Product Company To kill SARS- Contact -

Prospects of Replication-Deficient Adenovirus Based Vaccine Development Against SARS-Cov-2

Brief Report Prospects of Replication-Deficient Adenovirus Based Vaccine Development against SARS-CoV-2 Mariangela Garofalo 1,* , Monika Staniszewska 2 , Stefano Salmaso 1 , Paolo Caliceti 1, Katarzyna Wanda Pancer 3, Magdalena Wieczorek 3 and Lukasz Kuryk 3,4,* 1 Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, University of Padova, Via F. Marzolo 5, 35131 Padova, Italy; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (P.C.) 2 Chair of Drug and Cosmetics Biotechnology, Faculty of Chemistry, Warsaw University of Technology, Noakowskiego 3, 00-664 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Virology, National Institute of Public Health—National Institute of Hygiene, Chocimska 24, 00-791 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] (K.W.P.); [email protected] (M.W.) 4 Clinical Science, Targovax Oy, Saukonpaadenranta 2, 00180 Helsinki, Finland * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (L.K.) Received: 1 May 2020; Accepted: 6 June 2020; Published: 10 June 2020 Abstract: The current appearance of the new SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and it quickly spreading across the world poses a global health emergency. The serious outbreak position is affecting people worldwide and requires rapid measures to be taken by healthcare systems and governments. Vaccinations represent the most effective strategy to prevent the epidemic of the virus and to further reduce morbidity and mortality with long-lasting effects. Nevertheless, currently there are no licensed vaccines for the novel coronaviruses. Researchers and clinicians from all over the world are advancing the development of a vaccine against novel human SARS-CoV-2 using various approaches. -

A Human Coronavirus Evolves Antigenically to Escape Antibody Immunity

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.17.423313; this version posted December 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. A human coronavirus evolves antigenically to escape antibody immunity Rachel Eguia1, Katharine H. D. Crawford1,2,3, Terry Stevens-Ayers4, Laurel Kelnhofer-Millevolte3, Alexander L. Greninger4,5, Janet A. Englund6,7, Michael J. Boeckh4, Jesse D. Bloom1,2,# 1Basic Sciences and Computational Biology, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA 2Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 3Medical Scientist Training Program, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 4Vaccine and Infectious Diseases Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA 5Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 6Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, WA USA 7Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA USA 8Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Seattle, WA 98109 #Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract There is intense interest in antibody immunity to coronaviruses. However, it is unknown if coronaviruses evolve to escape such immunity, and if so, how rapidly. Here we address this question by characterizing the historical evolution of human coronavirus 229E. We identify human sera from the 1980s and 1990s that have neutralizing titers against contemporaneous 229E that are comparable to the anti-SARS-CoV-2 titers induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination. -

Genome Organization of Canada Goose Coronavirus, a Novel

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genome Organization of Canada Goose Coronavirus, A Novel Species Identifed in a Mass Die-of of Received: 14 January 2019 Accepted: 25 March 2019 Canada Geese Published: xx xx xxxx Amber Papineau1,2, Yohannes Berhane1, Todd N. Wylie3,4, Kristine M. Wylie3,4, Samuel Sharpe5 & Oliver Lung 1,2 The complete genome of a novel coronavirus was sequenced directly from the cloacal swab of a Canada goose that perished in a die-of of Canada and Snow geese in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, Canada. Comparative genomics and phylogenetic analysis indicate it is a new species of Gammacoronavirus, as it falls below the threshold of 90% amino acid similarity in the protein domains used to demarcate Coronaviridae. Additional features that distinguish the genome of Canada goose coronavirus include 6 novel ORFs, a partial duplication of the 4 gene and a presumptive change in the proteolytic processing of polyproteins 1a and 1ab. Viruses belonging to the Coronaviridae family have a single stranded positive sense RNA genome of 26–31 kb. Members of this family include both human pathogens, such as severe acute respiratory syn- drome virus (SARS-CoV)1, and animal pathogens, such as porcine epidemic diarrhea virus2. Currently, the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) recognizes four genera in the Coronaviridae family: Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus. While the reser- voirs of the Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus genera are believed to be bats, the Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus genera have been shown to spread primarily through birds3. Te frst three species of the Deltacoronavirus genus were discovered in 20094 and recent work has vastly expanded the Deltacoronavirus genus, adding seven additional species3. -

Broad Receptor Engagement of an Emerging Global Coronavirus May Potentiate Its Diverse Cross-Species Transmissibility

Broad receptor engagement of an emerging global coronavirus may potentiate its diverse cross-species transmissibility Wentao Lia,1, Ruben J. G. Hulswita,1, Scott P. Kenneyb,1, Ivy Widjajaa, Kwonil Jungb, Moyasar A. Alhamob, Brenda van Dierena, Frank J. M. van Kuppevelda, Linda J. Saifb,2, and Berend-Jan Boscha,2 aVirology Division, Department of Infectious Diseases & Immunology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, 3584 CL Utrecht, The Netherlands; and bDepartment of Veterinary Preventive Medicine, Food Animal Health Research Program, Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, The Ohio State University, Wooster, OH 44691 Contributed by Linda J. Saif, April 12, 2018 (sent for review February 15, 2018; reviewed by Tom Gallagher and Stefan Pöhlmann) Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV), identified in 2012, is a common greatly increase the potential for successful adaptation to a new enteropathogen of swine with worldwide distribution. The source host (6, 12). A pivotal criterion of cross-species transmission and evolutionary history of this virus is, however, unknown. concerns the ability of a virus to engage a receptor within the PDCoV belongs to the Deltacoronavirus genus that comprises pre- novel host, which for CoVs, is determined by the receptor dominantly avian CoV. Phylogenetic analysis suggests that PDCoV specificity of the viral spike (S) entry protein. originated relatively recently from a host-switching event be- The porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) is a recently discov- tween birds and mammals. Insight into receptor engagement by ered CoV of unknown origin. PDCoV (species name coronavirus PDCoV may shed light into such an exceptional phenomenon. Here HKU15) was identified in Hong Kong in pigs in the late 2000s we report that PDCoV employs host aminopeptidase N (APN) as an (13) and has since been detected in swine populations in various entry receptor and interacts with APN via domain B of its spike (S) countries worldwide (14–24). -

Human Coronavirus in the 2014 Winter Season As a Cause of Lower Respiratory Tract Infection

Original Article Yonsei Med J 2017 Jan;58(1):174-179 https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2017.58.1.174 pISSN: 0513-5796 · eISSN: 1976-2437 Human Coronavirus in the 2014 Winter Season as a Cause of Lower Respiratory Tract Infection Kyu Yeun Kim1, Song Yi Han1, Ho-Seong Kim1, Hyang-Min Cheong2, Sung Soon Kim2, and Dong Soo Kim1 1Department of Pediatrics, Severance Children’s Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul; 2Division of Respiratory Viruses, Center for Infectious Diseases, Korea National Institute of Health, Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Cheongju, Korea. Purpose: During the late autumn to winter season (October to December) in the Republic of Korea, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most common pathogen causing lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs). Interestingly, in 2014, human coronavirus (HCoV) caused not only upper respiratory infections but also LRTIs more commonly than in other years. Therefore, we sought to determine the epidemiology, clinical characteristics, outcomes, and severity of illnesses associated with HCoV infections at a sin- gle center in Korea. Materials and Methods: We retrospectively identified patients with positive HCoV respiratory specimens between October 2014 and December 2014 who were admitted to Severance Children’s Hospital at Yonsei University Medical Center for LRTI. Charts of the patients with HCoV infection were reviewed and compared with RSV infection. Results: During the study period, HCoV was the third most common respiratory virus and accounted for 13.7% of infections. Co- infection was detected in 43.8% of children with HCoV. Interestingly, one patient had both HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-NL63. -

Common Human Coronaviruses

Common Human Coronaviruses Common human coronaviruses, including types 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1, usually cause mild to moderate upper-respiratory tract illnesses, like the common cold. Most people get infected with one or more of these viruses at some point in their lives. This information applies to common human coronaviruses and should not be confused with Coronavirus Disease-2019 (formerly referred to as 2019 Novel Coronavirus). Symptoms of common human coronaviruses Treatment for common human coronaviruses • runny nose • sore throat There is no vaccine to protect you against human • headache • fever coronaviruses and there are no specific treatments for illnesses caused by human coronaviruses. Most people with • cough • general feeling of being unwell common human coronavirus illness will recover on their Human coronaviruses can sometimes cause lower- own. However, to relieve your symptoms you can: respiratory tract illnesses, such as pneumonia or bronchitis. • take pain and fever medications (Caution: do not give This is more common in people with cardiopulmonary aspirin to children) disease, people with weakened immune systems, infants, and older adults. • use a room humidifier or take a hot shower to help ease a sore throat and cough Transmission of common human coronaviruses • drink plenty of liquids Common human coronaviruses usually spread from an • stay home and rest infected person to others through If you are concerned about your symptoms, contact your • the air by coughing and sneezing healthcare provider. • close personal contact, like touching or shaking hands Testing for common human coronaviruses • touching an object or surface with the virus on it, then touching your mouth, nose, or eyes before washing Sometimes, respiratory secretions are tested to figure out your hands which specific germ is causing your symptoms. -

On the Coronaviruses and Their Associations with the Aquatic Environment and Wastewater

water Review On the Coronaviruses and Their Associations with the Aquatic Environment and Wastewater Adrian Wartecki 1 and Piotr Rzymski 2,* 1 Faculty of Medicine, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, 60-812 Pozna´n,Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Environmental Medicine, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, 60-806 Pozna´n,Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 24 April 2020; Accepted: 2 June 2020; Published: 4 June 2020 Abstract: The outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), a severe respiratory disease caused by betacoronavirus SARS-CoV-2, in 2019 that further developed into a pandemic has received an unprecedented response from the scientific community and sparked a general research interest into the biology and ecology of Coronaviridae, a family of positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses. Aquatic environments, lakes, rivers and ponds, are important habitats for bats and birds, which are hosts for various coronavirus species and strains and which shed viral particles in their feces. It is therefore of high interest to fully explore the role that aquatic environments may play in coronavirus spread, including cross-species transmissions. Besides the respiratory tract, coronaviruses pathogenic to humans can also infect the digestive system and be subsequently defecated. Considering this, it is pivotal to understand whether wastewater can play a role in their dissemination, particularly in areas with poor sanitation. This review provides an overview of the taxonomy, molecular biology, natural reservoirs and pathogenicity of coronaviruses; outlines their potential to survive in aquatic environments and wastewater; and demonstrates their association with aquatic biota, mainly waterfowl. It also calls for further, interdisciplinary research in the field of aquatic virology to explore the potential hotspots of coronaviruses in the aquatic environment and the routes through which they may enter it. -

Viroreal® Kit Bovine Coronavirus

Manual ViroReal® Kit Bovine Coronavirus Manual For use with the • ABI PRISM® 7500 (Fast) • LightCycler® 480 • Mx3005P® For veterinary use only DVEV00911, DVEV00913 100 DVEV00951, DVEV00953 50 ingenetix GmbH Arsenalstraße 11 1030 Vienna, Austria T +43(0)1 36 198 0 198 F +43(0)1 36 198 0 199 [email protected] www.ingenetix.com ingenetix GmbH ViroReal® Kit Bovine Coronavirus Manual June 2018 v1.5e Page 1 of 9 Manual Index 1. Product description ............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Pathogen information .......................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Principle of real-time PCR ................................................................................................................................... 3 4. General Precautions ........................................................................................................................................... 3 5. Contents of the Kit ............................................................................................................................................... 4 5.1. ViroReal® Kit Bovine Coronavirus order no. DVEV00911 or DVEV00951 .................................................. 4 5.2. ViroReal® Kit Bovine Coronavirus order no. DVEV00913 or DVEV00953 .................................................. 4 6. Additionally required materials and devices ....................................................................................................... -

Vacuolating Encephalitis in Mice Infected by Human Coronavirus OC43

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com R Virology 315 (2003) 20–33 www.elsevier.com/locate/yviro Vacuolating encephalitis in mice infected by human coronavirus OC43 He´le`ne Jacomy and Pierre J. Talbot* Laboratory of Neuroimmunovirology, INRS-Institut Armand Frappier, 531 Boulevard des Prairies, Laval, Que´bec, Canada H7V 1B7 Received 27 January 2003; returned to author for revision 5 March 2003; accepted 1 April 2003 Abstract Involvement of viruses in human neurodegenerative diseases and the underlying pathologic mechanisms remain generally unclear. Human respiratory coronaviruses (HCoV) can infect neural cells, persist in human brain, and activate myelin-reactive T cells. As a means of understanding the human infection, we characterized in vivo the neurotropic and neuroinvasive properties of HCoV-OC43 through the development of an experimental animal model. Virus inoculation of 21-day postnatal C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice led to a generalized infection of the whole CNS, demonstrating HCoV-OC43 neuroinvasiveness and neurovirulence. This acute infection targeted neurons, which underwent vacuolation and degeneration while infected regions presented strong microglial reactivity and inflammatory reactions. Damage to the CNS was not immunologically mediated and microglial reactivity was instead a consequence of direct virus-mediated neuronal injury. Although this acute encephalitis appears generally similar to that induced -

Coronaviruses: a Review of Their Properties and Diversity

Properties and diversity of coronaviruses Afr. J. Clin. Exper. Microbiol. 2020; 21 (4): 258-271 Joseph and Fagbami. Afr. J. Clin. Exper. Microbiol. 2020; 21 (4): 258 - 271 https://www.afrjcem.org African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology. ISSN 1595-689X Oct 2020; Vol.21 No.4 AJCEM/2038. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajcem Copyright AJCEM 2020: https://doi.org/10.4314/ajcem.v21i4.2 Review Article Open Access Coronaviruses: a review of their properties and diversity Joseph, A. A., and *Fagbami, A. H. Department of Microbial Pathology, Faculty of Basic Clinical Sciences, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo, Nigeria *Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract: Human coronaviruses, which hitherto were causative agents of mild respiratory diseases of man, have recently become one of the most important groups of pathogens of humans the world over. In less than two decades, three members of the group, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus (CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV, and SARS-COV-2, have emerged causing disease outbreaks that affected millions and claimed the lives of thousands of people. In 2017, another coronavirus, the swine acute diarrhea syndrome (SADS) coronavirus (SADS-CoV) emerged in animals killing over 24,000 piglets in China. Because of the medical and veterinary importance of coronaviruses, we carried out a review of available literature and summarized the current information on their properties and diversity. Coronaviruses are single-stranded RNA viruses with some unique characteristics such as the possession of a very large nucleic acid, high infidelity of the RNA-dependent polymerase, and high rate of mutation and recombination in the genome. -

Alignment-Free Machine Learning Approaches for the Lethality Prediction of Potential Novel Human-Adapted Coronavirus Using Genomic Nucleotide

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.15.176933; this version posted July 15, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Alignment-free machine learning approaches for the lethality prediction of potential novel human-adapted coronavirus using genomic nucleotide Rui Yin1,*, Zihan Luo2, Chee Keong Kwoh1 1 Biomedical Informatics Lab, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore 2 School of Electronic Information and Communications, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China * [email protected] Abstract A newly emerging novel coronavirus appeared and rapidly spread worldwide and World 1 Health Organization declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020. The roles and 2 characteristics of coronavirus have captured much attention due to its power of causing 3 a wide variety of infectious diseases, from mild to severe on humans. The detection of 4 the lethality of human coronavirus is key to estimate the viral toxicity and provide 5 perspective for treatment. We developed alignment-free machine learning approaches for 6 an ultra-fast and highly accurate prediction of the lethality of potential human-adapted 7 coronavirus using genomic nucleotide. We performed extensive experiments through six 8 different feature transformation and machine learning algorithms in combination with 9 digital signal processing to infer the lethality of possible future novel coronaviruses 10 using previous existing strains. The results tested on SARS-CoV, MERS-Cov and 11 SARS-CoV-2 datasets show an average 96.7% prediction accuracy.