Cavour, Garibaldi & the State of Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When the Demos Shapes the Polis - the Use of Referendums in Settling Sovereignty Issues

When the Demos Shapes the Polis - The Use of Referendums in Settling Sovereignty Issues. Gary Sussman, London School of Economics (LSE). Introduction This chapter is a survey of referendums dealing with questions of sovereignty. This unique category of referendum usage is characterized by the participation of the demos in determining the shape of the polis or the nature of its sovereignty. The very first recorded referendums, following the French Revolution, were sovereignty referendums. Though far from transparent and fair, these votes were strongly influenced by notions of self- determination and the idea that title to land could not be changed without the consent of those living on that land. Since then there have been over two hundred and forty sovereignty referendums. In the first part of this chapter I will briefly review referendum usage in general. This international analysis of 1094 referendums excludes the United States of America, where initiatives are extensively used by various states and Switzerland, which conducted 414 votes on the national level from 1866 to 1993. This comparative analysis of trends in referendum usage will provide both a sketch of the geographical distribution of use and a sense of use by issue. In the second section of this chapter I examine the history and origins of the sovereignty referendum and identify broad historical trends in its use. It will be demonstrated there have been several high tides in the use of sovereignty referendums and that these high tides are linked to high tides of nationalism, which have often followed the collapse of empires. Following this historical overview a basic typology of six sub-categories, describing sovereignty referendums will be suggested. -

The Italian Wars

198 Chapter 7 CHAPTER 7 Allegiance and Rebellion II: The Italian Wars The Italian Wars, with the irruption of the kings of France and Spain and the emperor into the state system of the peninsula, complicated questions of al- legiance for the military nobility throughout Italy. Many were faced with un- avoidable choices, on which could hang grave consequences for themselves and their families. These choices weighed most heavily on the barons of the kingdom of Naples and the castellans of Lombardy, the main areas of conten- tion among the ultramontane powers. The bulk of the military nobility in these regions harboured no great affection or loyalty towards the Sforza dukes of Mi- lan, Aragonese kings of Naples or Venetian patricians whose rule was chal- lenged. Accepting an ultramontane prince as their lord instead need not have occasioned them much moral anguish, provided they were left in possession of their lands. They might, indeed, hope that a non-resident prince would allow them a greater degree of autonomy. But there could be no guarantee that those who pledged their loyalty to an ultramontane prince would receive the bene- fits and the recognition they might have hoped for. Although the ideas, expec- tations and way of life of the Italian rural nobility had much in common with their German, French and Spanish counterparts who came to Italy as soldiers and officials, the ultramontanes generally assumed the air of conquerors, of superiority to Italians of whatever social rank. Members of different nations were often more conscious of their differences in language and customs than of any similarities in their values, and relations between the nobilities of the various nations were frequently imbued with mutual disparagement, rather than mutual respect. -

Military History of Italy 1 a Missing Peninsula?

The Military History of Italy 1 A Missing Peninsula? Why We Need A New Geostrategic History Of the Central Peninsula of the Mediterranean Twenty-two years ago, in the introduction to his famous Twilight of a military tra- dition, Gregory Hanlon reported the irony with which his colleagues had accepted his plan to study the Italian military value 1. The topic of the Italian cowardice, however, predates the deeds of the Sienese nobility in the Thirty Years War that fascinated Hanlon to transform a social historian into one of the few foreign specialists in the military history of modern Italy. In fact, it dates back to the famous oxymoron of the Italum bellacem which appeared in the second edition of Erasmus’ Adagia , five years after the famous Disfida of Barletta (1503) and was then fiercely debated after the Sack of Rome in 1527 2. Historiography, both Italian and foreign, has so far not inves- tigated the reasons and contradictions of this longstanding stereotype. However, it seems to me a "spy", in Carlo Ginzburg’s sense, of a more general question, which in my opinion explains very well why Italians excel in other people’s wars and do not take their own seriously. The question lies in the geostrategic fate of the Central Mediterranean Peninsula, at the same time Bridge and Front between West and East, between Oceàna and Eura- sia, as it already appears in the Tabula Peutingeriana : the central and crucial segment between Thule and Taprobane. An Italy cut transversely by the Apennines extended ‘Westwards’ by the Ticino River, with two Italies – Adriatic and Tyrrhenian – marked by ‘manifest destinies’ that are different from each other and only at times brought to- gether 3. -

The Great European Treaties of the Nineteenth Century

JBRART Of 9AN DIEGO OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY EDITED BY SIR AUGUSTUS OAKES, CB. LATELY OF THE FOREIGN OFFICE AND R. B. MOWAT, M.A. FELLOW AND ASSISTANT TUTOR OF CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, OXFORD WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIR H. ERLE RICHARDS K. C.S.I., K.C., B.C.L., M.A. FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE AWD CHICHELE PROFESSOR OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND DIPLOMACY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD ASSOCIATE OF THE INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, E.C. 4 LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW LEIPZIG NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPETOWN BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS SHANGHAI HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY Impression of 1930 First edition, 1918 Printed in Great Britain INTRODUCTION IT is now generally accepted that the substantial basis on which International Law rests is the usage and practice of nations. And this makes it of the first importance that the facts from which that usage and practice are to be deduced should be correctly appre- ciated, and in particular that the great treaties which have regulated the status and territorial rights of nations should be studied from the point of view of history and international law. It is the object of this book to present materials for that study in an accessible form. The scope of the book is limited, and wisely limited, to treaties between the nations of Europe, and to treaties between those nations from 1815 onwards. To include all treaties affecting all nations would require volumes nor is it for the many ; necessary, purpose of obtaining a sufficient insight into the history and usage of European States on such matters as those to which these treaties relate, to go further back than the settlement which resulted from the Napoleonic wars. -

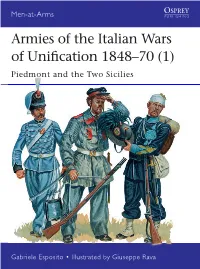

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy. -

Mont Blanc in British Literary Culture 1786 – 1826

Mont Blanc in British Literary Culture 1786 – 1826 Carl Alexander McKeating Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Leeds School of English May 2020 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Carl Alexander McKeating to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Carl Alexander McKeating in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Frank Parkinson, without whose scholarship in support of Yorkshire-born students I could not have undertaken this study. The Frank Parkinson Scholarship stipulates that parents of the scholar must also be Yorkshire-born. I cannot help thinking that what Parkinson had in mind was the type of social mobility embodied by the journey from my Bradford-born mother, Marie McKeating, who ‘passed the Eleven-Plus’ but was denied entry into a grammar school because she was ‘from a children’s home and likely a trouble- maker’, to her second child in whom she instilled a love of books, debate and analysis. The existence of this thesis is testament to both my mother’s and Frank Parkinson’s generosity and vision. Thank you to David Higgins and Jeremy Davies for their guidance and support. I give considerable thanks to Fiona Beckett and John Whale for their encouragement and expert interventions. -

Ÿþe L E V E N T H R E P O R T O N S U C C E S S I O N O F S T a T E S I N R E S P E C T O F M a T T E R

Document:- A/CN.4/322 and Corr.1 & Add.1 & 2 Eleventh report on succession of States in respect of matters other than treaties, by Mr. Mohamed Bedjaoui, Special Rapporteur - draft articles on succession in respect of State archives, with commentaries Topic: Succession of States in respect of matters other than treaties Extract from the Yearbook of the International Law Commission:- 1979, vol. II(1) Downloaded from the web site of the International Law Commission (http://www.un.org/law/ilc/index.htm) Copyright © United Nations SUCCESSION OF STATES IN RESPECT OF MATTERS OTHER THAN TREATIES [Agenda item 3] DOCUMENT A/CN.4/322 AND ADD.l AND 2* Eleventh report on succession of States in respect of matters other than treaties, by Mr. Mohammed Bedjaoui, Special Rapporteur Draft articles on succession in respect of State archives, with commentaries [Original: French] [18,29 and 31 May 1979] CONTENTS Page Abbreviation 68 Explanatory note: italics in quotations 68 Paragraphs Introduction 1_5 68 Chapter I. STATE ARCHIVES IN MODERN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND IN THE SUCCESSION OF STATES 6-91 71 A. Definition of archives affected by the succession of States 6-24 71 1. Content of the concept of archives 8-19 72 2. Definition of archives in the light of State practice in the matter of succession of States 20-24 74 B. The role of archives in the modern world 25-39 75 1. The "paper war" 25-32 75 2. The age of information 33-39 77 C. The claim to archives and the protection of the national cultural heritage 40-56 78 1. -

The White Horse Press Full Citation: Crook, D.S. D.J. Siddle, R.T. Jones, J.A. Dearing, G.C. Foster and R. Thompson. "Fores

The White Horse Press Full citation: Crook, D.S. D.J. Siddle, R.T. Jones, J.A. Dearing, G.C. Foster and R. Thompson. "Forestry and Flooding in the Annecy Petit Lac Catchment, Haute-Savoie 1730–2000." Environment and History 8, no. 4 (November 2002): 403–28. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/3135. Rights: All rights reserved. © The White Horse Press 2002. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this article may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the publishers. For further information please see http://www.whpress.co.uk. Forestry and Flooding in the Annecy Petit Lac Catchment, Haute-Savoie 1730–2000 D.S. CROOK*, D.J. SIDDLE, R.T. JONES, J.A. DEARING, G.C.FOSTER Department of Geography University of Liverpool Liverpool L69 7ZT, UK R. THOMPSON Department of Geology and Geophysics University of Edinburgh Edinburgh, UK *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Upland environments are particularly vulnerable to the stresses of climate change. The strength and persistence of such forces are not easy to measure and hence comparison of climate impacts with anthropogenic impacts has remained problematic. This paper attempts to demonstrate the nature of human impact on forest cover and flooding in the Annecy Petit Lac Catchment in pre-Alpine Haute Savoie, France, between 1730 and 2000. Local documentary sources and a pollen record provided a detailed history of forest cover and management, making it possible to plot changes in forest cover against local and regional precipitation records, and their individual and combined impacts on flooding. -

ICRP Calendar

The notions of International Relations (IR) in capital letters and international relations (ir) in lowercase letters have two different meanings. The first refers to a scholarly discipline while the second one means a set of contemporary events with historical importance, which influences global-politics. In order to make observations, formulate theories and describe patterns within the framework of ‘IR’, one needs to fully comprehend specific events related to ‘ir’. It is why the Institute for Cultural Relations Policy (ICRP) believes that a timeline on which all the significant events of international relations are identified might be beneficial for students, scholars or professors who deal with International Relations. In the following document all the momentous wars, treaties, pacts and other happenings are enlisted with a monthly division, which had considerable impact on world-politics. January 1800 | Nationalisation of the Dutch East Indies The Dutch East Indies was a Dutch colony that became modern Indonesia following World War II. It was formed 01 from the nationalised colonies of the Dutch East India Company, which came under the administration of the Dutch government in 1800. 1801 | Establishment of the United Kingdom On 1 January 1801, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland united to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Most of Ireland left the union as the Irish Free State in 1922, leading to the remaining state being renamed as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1927. 1804 | Haiti independence declared The independence of Haiti was recognized by France on 17 April 1825. -

Unity Deferred: the "Roman Question" in Italian History,1861-82 William C Mills

Unity Deferred: The "Roman Question" in Italian History,1861-82 William C Mills ABSTRACT: Following the Risorgimento (the unification of the kingdom of Italy) in 1861, the major dilemma facing the new nation was that the city of Rome continued to be ruled by the pope as an independent state. The Vatican's rule ended in 1870 when the Italian army captured the city and it became the new capital of Italy. This paper will examine the domestic and international problems that were the consequences of this dispute. It will also review the circumstances that led Italy to join Germany and Austria in the Triple Alliance in 1882. In the early morning of 20 September 1870, Held guns of the Italian army breached the ancient city wall of Rome near the Porta Pia. Army units advanced to engage elements of the papal militia in a series of random skirmishes, and by late afternoon the army was in control of the city. Thus concluded a decade of controversy over who should govern Rome. In a few hours, eleven centuries of papal rule had come to an end.' The capture of Rome marked die first time that the Italian government had felt free to act against the explicit wishes of the recendy deposed French emperor, Napoleon III. Its action was in sharp contrast to its conduct in the previous decade. During that time, die Italians had routinely deferred to Napoleon with respect to the sanctity of Pope Pius IX's rule over Rome. Yet while its capture in 1870 revealed a new sense of Italian independence, it did not solve the nation's dilemma with the Roman question. -

At the Helm of the Republic: the Origins of Venetian Decline in the Renaissance

At the Helm of the Republic: The Origins of Venetian Decline in the Renaissance Sean Lee Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Georgetown University Advisor(s): Professor Jo Ann Moran Cruz Honors Program Chair: Professor Alison Games May 4, 2020 Lee 1 Contents List of Illustrations 2 Acknowledgements 3 Terminology 4 Place Names 5 List of Doges of Venice (1192-1538) 5 Introduction 7 Chapter 1: Constantinople, The Crossroads of Empire 17 Chapter 2: In Times of Peace, Prepare for War 47 Chapter 3: The Blinding of the Lion 74 Conclusion 91 Bibliography 95 Lee 2 List of Illustrations Figure 0.1. Map of the Venetian Terraferma 8 Figure 1.1. Map of the Venetian and Ottoman Empires 20 Figure 1.2. Tomb of the Tiepolo Doges 23 Figure 1.3. Map of the Maritime Empires of Venice and Genoa (1453) 27 Figure 1.4. Map of the Siege of Constantinople (1453) 31 Figure 2.1. Map of the Morea 62 Figure 2.2. Maps of Negroponte 65 Figure 3.1. Positions of Modone and Corone 82 Lee 3 Acknowledgements If brevity is the soul of wit, then I’m afraid you’re in for a long eighty-some page thesis. In all seriousness, I would like to offer a few, quick words of thanks to everybody in the history department who has helped my peers and me through this year long research project. In particular I’d like to thank Professor Ágoston for introducing me to this remarkably rich and complex period of history, of which I have only scratched the surface. -

Sabaudian States

Habent sua fata libelli EARLY MODERN STUDIES SERIES GENEraL EDITOR MICHAEL WOLFE St. John’s University EDITORIAL BOARD OF EARLY MODERN STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN raYMOND A. MENTZER Framingham State College University of Iowa ChRISTOPHER CELENZA ChARLES G. NAUERT Johns Hopkins University University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBAra B. DIEFENDORF ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Boston University Truman State University, Emeritus PAULA FINDLEN NICHOLAS TERPSTra Stanford University University of Toronto SCOtt H. HENDRIX MARGO TODD Princeton Theological Seminary University of Pennsylvania JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON JAMES TraCY University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Minnesota MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Sabaudian Studies Political Culture, Dynasty, & Territory 1400–1700 Edited by Matthew Vester Early Modern Studies 12 Truman State University Press Kirksville, Missouri Copyright © 2013 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover art: Sabaudia Ducatus—La Savoie, copper engraving with watercolor highlights, 17th century, Paris. Photo by Matthew Vester. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sabaudian Studies : Political Culture, Dynasty, and Territory (1400–1700) / [compiled by] Matthew Vester. p. cm. — (Early Modern Studies Series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61248-094-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-61248-095-4 (ebook) 1. Savoy, House of. 2. Savoy (France and Italy)—History. 3. Political culture—Savoy (France and Italy)—History. I. Vester, Matthew A. (Matthew Allen), author, editor of compilation. DG611.5.S24 2013 944'.58503—dc23 2012039361 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without writ- ten permission from the publisher.