The Italian Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Napoli'den Istanbul'a

Calendario Di Meo 2019 NAPOLI’DEN ISTANBUL’A FOTOGRAFIE DI MASSIMO LISTRI ASSOCIAZIONE CULTURALE “DI MEO VINI AD ARTE” Sono particolarmente lieto che l’edizione 2019 del prestigioso calendario dei fratelli di Meo Ailesi’nin fahri kültür elçiliğinin en güzel örneklerinden birini teşkil eden prestij Generoso e Roberto di Meo offra una scintillante visione della splendida città di Istanbul takvimlerinin 2019 yılı baskısında, dünyanın en görkemli ve en eski sürekli yerleşik e dei suoi profondi legami con un’altra perla del Mediterraneo: Napoli. Attraverso la şehirlerinden biri olan İstanbul’un seçilmesinden ve bu nadide şehirle asırlar boyunca storia di queste due Capitali possiamo così intravedere l’intreccio di storia e cultura che Akdeniz’in güzide şehirlerinden biri olan Napoli’nin irtibatlandırılmasından büyük lega da secoli l’Italia e la Turchia. Le splendide immagini del maestro Massimo Listri e bir memnuniyet duydum. gli stimolanti scritti dei tanti studiosi e intellettuali che hanno contribuito al calendario ci Takvimde yer verilen fotoğraflar ve değerli ustalarca kaleme alınmış metinler, yalnızca permettono di cogliere le caratteristiche profonde che accomunano Napoli e Istanbul: la İstanbul ve Napoli’nin tatlarındaki, renklerindeki, dokularındaki ve tınılarındaki loro natura di approdo e di luogo di incontro e di scambio sin dall’antichità; il loro benzerlikleri ortaya çıkarmakla kalmıyor, aynı zamanda Türkiye ve İtalya’nın indissolubile legame con il mare; il crogiuolo di lingue, culture e tradizioni che vi si è yüzyıllardan beri sahip olduğu derin sosyal ve kültürel etkileşimi tarihsel bir perspektif sedimentato nei secoli; l’esplosione dei suoni e dei colori accanto a ombre e misteri içerisinde ve masalsı bir anlatımla gözler önüne seriyor. -

Bartolomé De Las Casas, Soldiers of Fortune, And

HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Dissertation Submitted To The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Damian Matthew Costello UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August 2013 HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew APPROVED BY: ____________________________ Dr. William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Chair ____________________________ Dr. Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Anthony B. Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member _____________________________ Dr. Roberto S. Goizueta, Ph.D. Committee Member ii ABSTRACT HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier This dissertation - a postcolonial re-examination of Bartolomé de las Casas, the 16th century Spanish priest often called “The Protector of the Indians” - is a conversation between three primary components: a biography of Las Casas, an interdisciplinary history of the conquest of the Americas and early Latin America, and an analysis of the Spanish debate over the morality of Spanish colonialism. The work adds two new theses to the scholarship of Las Casas: a reassessment of the process of Spanish expansion and the nature of Las Casas’s opposition to it. The first thesis challenges the dominant paradigm of 16th century Spanish colonialism, which tends to explain conquest as the result of perceived religious and racial difference; that is, Spanish conquistadors turned to military force as a means of imposing Spanish civilization and Christianity on heathen Indians. -

MCMANUS-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (4.095Mb)

The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation McManus, Stuart Michael. 2016. The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493519 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World A dissertation presented by Stuart Michael McManus to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Stuart Michael McManus All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: James Hankins, Tamar Herzog Stuart Michael McManus The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World Abstract Historians have long recognized the symbiotic relationship between learned culture, urban life and Iberian expansion in the creation of “Latin” America out of the ruins of pre-Columbian polities, a process described most famously by Ángel Rama in his account of the “lettered city” (ciudad letrada). This dissertation argues that this was part of a larger global process in Latin America, Iberian Asia, Spanish North Africa, British North America and Europe. -

Tommaso Astarita Naples Was One of the Largest Cities in Early Modern

INTRODUCTION: “NAPLES IS THE WHOLE world” Tommaso Astarita Naples was one of the largest cities in early modern Europe and, for about two centuries, the largest city in the global empire ruled by the kings of Spain. Its crowded and noisy streets, the height of its buildings, the num- ber and wealth of its churches and palaces, the celebrated natural beauty of its location, the many antiquities scattered in its environs, the fiery volcano looming over it, the drama of its people’s devotions, and the size and liveliness—to put it mildly—of its plebs all made Naples renowned and at times notorious across Europe. The new essays in this volume aim to introduce this important, fasci- nating, and bewildering city to readers unfamiliar with its history. In this introduction, I will briefly situate the city in the general history of Italy and Europe and offer a few remarks on the themes, topics, and approaches of the essays that follow. The city of Naples was founded by Greek settlers in the 6th century BC (although earlier settlements in the area date to the 9th century). Greeks, Etruscans, and, eventually, Romans vied for control over the city during its first few centuries. After Rome absorbed the southern areas of the Ital- ian Peninsula, Naples followed the history of the Roman state; however, through much of that era, it maintained a strong Greek identity and cul- ture. (Nero famously chose to make his first appearance on the stage in Naples, finding the city’s Greek culture more tolerant than stern Rome of such behavior.) Perhaps due to its continued eastern orientation, Naples developed an early Christian community. -

Military History of Italy 1 a Missing Peninsula?

The Military History of Italy 1 A Missing Peninsula? Why We Need A New Geostrategic History Of the Central Peninsula of the Mediterranean Twenty-two years ago, in the introduction to his famous Twilight of a military tra- dition, Gregory Hanlon reported the irony with which his colleagues had accepted his plan to study the Italian military value 1. The topic of the Italian cowardice, however, predates the deeds of the Sienese nobility in the Thirty Years War that fascinated Hanlon to transform a social historian into one of the few foreign specialists in the military history of modern Italy. In fact, it dates back to the famous oxymoron of the Italum bellacem which appeared in the second edition of Erasmus’ Adagia , five years after the famous Disfida of Barletta (1503) and was then fiercely debated after the Sack of Rome in 1527 2. Historiography, both Italian and foreign, has so far not inves- tigated the reasons and contradictions of this longstanding stereotype. However, it seems to me a "spy", in Carlo Ginzburg’s sense, of a more general question, which in my opinion explains very well why Italians excel in other people’s wars and do not take their own seriously. The question lies in the geostrategic fate of the Central Mediterranean Peninsula, at the same time Bridge and Front between West and East, between Oceàna and Eura- sia, as it already appears in the Tabula Peutingeriana : the central and crucial segment between Thule and Taprobane. An Italy cut transversely by the Apennines extended ‘Westwards’ by the Ticino River, with two Italies – Adriatic and Tyrrhenian – marked by ‘manifest destinies’ that are different from each other and only at times brought to- gether 3. -

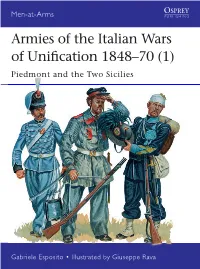

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy. -

Long-Term Trends in Economic Inequality in Southern Italy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio della ricerca - Università degli studi di Napoli Federico II Guido Alfani PAM and Dondena Centre – Bocconi University Via Roentgen 1, 20136 Milan, Italy [email protected] Sergio Sardone Dondena Centre – Bocconi University Via Roentgen 1, 20136 Milan, Italy [email protected] Long-term trends in economic inequality in southern Italy. The Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, 16 th -18 th centuries: First results 1 Abstract This paper uses new archival data collected by an ERC-funded research project, EINITE-Economic Inequality across Italy and Europe, 1300-1800 , to study the long-term tendencies in economic inequality in preindustrial southern Italy (Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily). The paper reconstructs long-term trends in inequality, especially of wealth, for the period 1550-1800 and also produces regional estimates of overall inequality levels in Apulia, which are compared with those now available for some regions of central-northern Italy (Piedmont, Tuscany). As much of the early modern period the Kingdom of Naples was overall a stagnating economy, this is a particularly good case for exploring the relationship between economic growth and inequality change. Keywords Economic inequality; income inequality; wealth inequality; early modern period; Kingdom of Naples; Apulia; Sicily; Italy; poverty Acknowledgements We are grateful to Alessia Lo Storto, who helped collect data from the mid-18 th century catasto onciario , and to Davide De Franco, who elaborated the GIS maps we use. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC Grant agreement n° 283802, starting date 1 January 2012. -

Unity Deferred: the "Roman Question" in Italian History,1861-82 William C Mills

Unity Deferred: The "Roman Question" in Italian History,1861-82 William C Mills ABSTRACT: Following the Risorgimento (the unification of the kingdom of Italy) in 1861, the major dilemma facing the new nation was that the city of Rome continued to be ruled by the pope as an independent state. The Vatican's rule ended in 1870 when the Italian army captured the city and it became the new capital of Italy. This paper will examine the domestic and international problems that were the consequences of this dispute. It will also review the circumstances that led Italy to join Germany and Austria in the Triple Alliance in 1882. In the early morning of 20 September 1870, Held guns of the Italian army breached the ancient city wall of Rome near the Porta Pia. Army units advanced to engage elements of the papal militia in a series of random skirmishes, and by late afternoon the army was in control of the city. Thus concluded a decade of controversy over who should govern Rome. In a few hours, eleven centuries of papal rule had come to an end.' The capture of Rome marked die first time that the Italian government had felt free to act against the explicit wishes of the recendy deposed French emperor, Napoleon III. Its action was in sharp contrast to its conduct in the previous decade. During that time, die Italians had routinely deferred to Napoleon with respect to the sanctity of Pope Pius IX's rule over Rome. Yet while its capture in 1870 revealed a new sense of Italian independence, it did not solve the nation's dilemma with the Roman question. -

At the Helm of the Republic: the Origins of Venetian Decline in the Renaissance

At the Helm of the Republic: The Origins of Venetian Decline in the Renaissance Sean Lee Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Georgetown University Advisor(s): Professor Jo Ann Moran Cruz Honors Program Chair: Professor Alison Games May 4, 2020 Lee 1 Contents List of Illustrations 2 Acknowledgements 3 Terminology 4 Place Names 5 List of Doges of Venice (1192-1538) 5 Introduction 7 Chapter 1: Constantinople, The Crossroads of Empire 17 Chapter 2: In Times of Peace, Prepare for War 47 Chapter 3: The Blinding of the Lion 74 Conclusion 91 Bibliography 95 Lee 2 List of Illustrations Figure 0.1. Map of the Venetian Terraferma 8 Figure 1.1. Map of the Venetian and Ottoman Empires 20 Figure 1.2. Tomb of the Tiepolo Doges 23 Figure 1.3. Map of the Maritime Empires of Venice and Genoa (1453) 27 Figure 1.4. Map of the Siege of Constantinople (1453) 31 Figure 2.1. Map of the Morea 62 Figure 2.2. Maps of Negroponte 65 Figure 3.1. Positions of Modone and Corone 82 Lee 3 Acknowledgements If brevity is the soul of wit, then I’m afraid you’re in for a long eighty-some page thesis. In all seriousness, I would like to offer a few, quick words of thanks to everybody in the history department who has helped my peers and me through this year long research project. In particular I’d like to thank Professor Ágoston for introducing me to this remarkably rich and complex period of history, of which I have only scratched the surface. -

Amsterdam International Antiquarian Book Fair 2016

Amsterdam International Antiquarian Book Fair 2016 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS Visit us also at the: Boston International Book Fair 28-30 October 2016 China in Print (Hong Kong) 18-20 November 2016 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS 720 High Street Armadale Melbourne VIC 3143 Australia +61 3 9066 0200 [email protected] To add your details to our email list for monthly New Acquisitions, visit douglasstewart.com.au © Douglas Stewart Fine Books 2016 Amsterdam International Antiquarian Book Fair Amsterdam Marriott Hotel 1-2 October 2016 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS [EMPEROR ZHU YUANZHANG (MING TAIZU), 1328-1398] 1. A 14th century Ming Dynasty 1 kuan note : an example of the oldest extant paper currency [China : c.1375]. Printed during the reign (1368-1398) of the frst Ming emperor, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang (Ming Taizu), a paper note with the original cash value of a string of 1,000 copper coins, or 1 kuan. Woodblock printed in black ink on a sheet of grey mulberry paper, 340 x 220 mm; recto with the Chinese characters Da Ming tong xing bao chao ("Great Ming Circulating Treasure Certifcate") at head; beneath this is a wide decorative border with dragon motif; at the centre, the denomination is written in two characters, yi guan ("one string"), with pictorial representations of ten piles of 100 copper coins and further registers of text including instructions for use and the phrase "To circulate forever", along with warnings of the severe punishments for counterfeiters and an offer of reward for those who inform against them; two authorising seals in vermilion ink, the frst of which reads “Seal of the Treasure Note of the Great Ming Dynasty", and the second “Seal of the Offce of the Superintendent of the Treasury”; verso with repeated pictorial woodblock print and one of the vermilion seals; original horizontal fold; some insignifcant loss at left margin and a tiny perforation in the lower section, else a fne, strongly printed example; protected in an archival portfolio and housed in a custom clam shell box with calf title label lettered in gilt. -

CHAPTER I the FORMATIVE YEARS in 1754, David Hume Began The

CHAPTER I THE FORMATIVE YEARS In 1754, David Hume began the publication of his Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects in London; Linnaeus published his Genera Plantarum in Stockholm; and in Paris Condillac’s Traité des sensations and Diderot’s Interprétation de la nature came off the presses. Also, in Russia, the first bank was founded; in Haarlem, the Literary Society was established; and, in Spain, Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa became members of the Chamber of Commerce. In short, although alternating between periods of slow and of feverish creative activity, the intellectual climate throughout Europe was maturing rapidly in preparation for the coming golden age, an era whose spirit was to be found in the plans, projects, and legislative proceedings of its statesmen over the next twenty years. However, at mid-century there were still some regions that remained impervious to this intellectual ferment. They were unaware of the philosophical, scientific and economic debate that was taking place in the major capitals, and unaware too of the emerging nucleus of the bourgeoisie that would soon demand, and by the end of the century realize, the fulfilment of its role in history. In Italy, Lunigiana was one of these stagnant regions. This territory, which extends from the narrow valley of the Magra River to the peaks of the mountains that surround it on all sides, was fragmented into some fifteen miniscule fiefdoms, each of which was governed by one of the marquises of the Malaspina family, who were direct vassals of the Austrian emperor. These territories were surrounded by the Republic of Genoa, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, and the Duchy of Parma. -

Sabaudian States

Habent sua fata libelli EARLY MODERN STUDIES SERIES GENEraL EDITOR MICHAEL WOLFE St. John’s University EDITORIAL BOARD OF EARLY MODERN STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN raYMOND A. MENTZER Framingham State College University of Iowa ChRISTOPHER CELENZA ChARLES G. NAUERT Johns Hopkins University University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBAra B. DIEFENDORF ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Boston University Truman State University, Emeritus PAULA FINDLEN NICHOLAS TERPSTra Stanford University University of Toronto SCOtt H. HENDRIX MARGO TODD Princeton Theological Seminary University of Pennsylvania JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON JAMES TraCY University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Minnesota MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Sabaudian Studies Political Culture, Dynasty, & Territory 1400–1700 Edited by Matthew Vester Early Modern Studies 12 Truman State University Press Kirksville, Missouri Copyright © 2013 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover art: Sabaudia Ducatus—La Savoie, copper engraving with watercolor highlights, 17th century, Paris. Photo by Matthew Vester. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sabaudian Studies : Political Culture, Dynasty, and Territory (1400–1700) / [compiled by] Matthew Vester. p. cm. — (Early Modern Studies Series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61248-094-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-61248-095-4 (ebook) 1. Savoy, House of. 2. Savoy (France and Italy)—History. 3. Political culture—Savoy (France and Italy)—History. I. Vester, Matthew A. (Matthew Allen), author, editor of compilation. DG611.5.S24 2013 944'.58503—dc23 2012039361 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without writ- ten permission from the publisher.