UCL Beacon for Public Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Autumn Festival of Art, Knowledge and Imagination Bloomsburyfestival.Org.Uk | Follow Us: @Bloomsburyfest #Bloomsburyfest Introduction Introduction

FREE! An autumn festival of art, knowledge and imagination bloomsburyfestival.org.uk | Follow us: @bloomsburyfest #bloomsburyfest Introduction Introduction As the new Festival Director, I am proud to present the Welcome to the Bloomsbury 2013“ Bloomsbury Festival programme, created and led by the people that live, work, study and play in this small but beautiful corner of London. Bloomsbury Festival shines a light on the self Festival determination of a world-changing community of pioneers existing side- by-side across a few streets. This October the Bloomsbury Festival spills out into the area’s streets, Virginia Woolf once spoke of her sense of freedom upon arriving in Bloomsbury, and I seek shops, museums, libraries and laboratories with a truly eclectic to recapture that same spirit of vitality in every visitor this year. I welcome you into our sanctuary for line-up of unexpected, enlightening and extraordinary things to see and do. Take a the imagination to encounter brilliant minds, relaxation and pleasure, the new and the controversial. musicals masterclass from Sir Tim Rice, hear Turner Prize winner Mark Wallinger in Bloomsbury Festival is an uplifting journey of discovery that aims to inspire, delight, surprise and conversation, listen to Iain Sinclair on Bloomsbury and radicalism, and discover Sir move you. Andrew Motion’s personal literary refuges. As a registered charity we also run a year-round outreach festival for the lonely, taking the best of Bloomsbury right into the living rooms of local isolated people such as those living with dementia. We’ve extended the festival to six days, giving you more time to explore over 200 free Please donate to help continue this vital service and ensure our Festival is kept free for everyone to events across Bloomsbury. -

201819 Master Contract List FINAL 11072018 to Be Added to Website.Xlsx

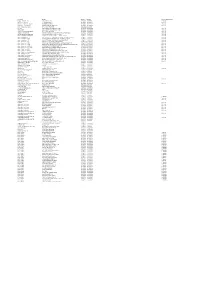

Description Provider Start Date End Date Contract Notice Period Diagnostic Services ‐ ISTC InHealth Netcare Ltd 01/07/2014 30/06/2018 12 Months Specialist Pallative Care ST JOSEPHS HOSPICE 01/04/2016 01/03/2019 1 Month Pallative care (Childrens hospice) RICHARD HOUSE TRUST 01/04/2016 31/03/2019 7 Months HIV Services ‐ non consortia MILDMAY MISSION HOSPITAL UK 01/04/2016 31/03/2019 3 Months Newham Urgent Care Centre BARTS HEALTH NHS TRUST 20/11/2013 31/05/2018 ELFT CHS EAST LONDON NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 3 Months Mental Health EAST LONDON NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 7 Months Acute ‐ In Area SLA ‐ Barts Health BARTS HEALTH NHS TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ In Area SLA ‐ HUH HOMERTON UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Ambulance Service ‐ Urgent Care LONDON AMBULANCE SERVICE NHS TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 3 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ Moorfields MOORFIELDS EYE HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ UCLH UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ BHRUT BARKING HAVERING AND REDBRIDGE HOSPITALS NHS TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ GST GUYS & ST THOMAS HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ ICH IMPERIAL COLLEGE HEALTHCARE NHS TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ C&W CHELSEA AND WESTMINSTER HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ -

Online Journals List for Moorfields Eye Hospital Staff

Online Journals List for Moorfields Eye Hospital Staff Joint Library of Ophthalmology, Moorfields Eye Hospital & UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, 11-43 Bath Street, London EC1V 9EL Tel.: +44 (0)20 7608 6814 (MEH internal extension: 2084) E-mail: [email protected] Web: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/library/libraries-and-study-spaces/ophthalmology Moorfields Eye Hospital staff members have access to a number of ejournals via NHS Athens. To register for NHS Athens, please go to www.evidence.nhs.uk, select Journals and Databases, and then select Access journals. A complete list of ejournals available to Moorfields Eye Hospital staff members can be found at www.evidence.nhs.uk. Please select Journals and Databases and then Journals. Remember to log into Athens before accessing the ejournals, or you will not see the full list of titles available to you. Ejournals available cover most aspects of biomedicine and health. A list of eye and vision titles is provided below as a guide. Sometimes there are multiple entries for the same journal. Where this occurs the list aims to guide you to the best provider to use and provides instruction on how to reach the page successfully. Should you experience any problems please do not hesitate to contact a member of library staff who will take you through step by step. Title Holdings and (provider) Acta Ophthalmologica 1997- one year ago (Wiley Online Library free content)- look for open padlock for free access American Journal of Ophthalmology 2007- (ClinicalKey Wayfless) (earlier volumes from 1997- Hospital Premium Collection) American Journal of Ophthalmology Case Reports 2016- American Journal of Optometry August 1925-1940 (LWW Legacy Archive) click on OpenAthens Login American Journal of Optometry and Archives of American Academy of 1941- 1973 (LWW Definitive Archive) click on OpenAthens Optometry Login American Journal of Optometry and Physiological Optics 1974-1988 (LWW Definitive Archive) click on OpenAthens Login Archives of Ophthalmology 1998 - 2012 (from vol. -

Dr. Robin Philipp Professor Michael Baum Reverend Andrew Mawson Sir Kenneth Caiman Published by the Nuffield Trust 59 New Cavendish Street London W1M 7RD

Nuffield Trust Series No. 10 Beyond the Millennium Windsor I Cumberland Lodge, Windsor Great Park 12th & 13th March 1998 A summary of the proceedings of the first Windsor Conference Dr. Robin Philipp Professor Michael Baum Reverend Andrew Mawson Sir Kenneth Caiman Published by The Nuffield Trust 59 New Cavendish Street London W1M 7RD Telephone: 0171 631 8450 Facsimile: 0171 631 8451 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk ISBN: 1 902089 24 3 © Nuffield Trust 1999 Publications Committee Professor John Ledingham DM, FRCP Dame Fiona Caldicott, DBE, FRCP, FRCPsych John Wyn Owen, CB CONTENTS Page Foreword 6 Acknowledgements 7 Section 1 The Windsor I Conference 8 The Objectives 11 Section 2 General Background 12 Section 3 Scene setting: Points from the Keynote Presentation of Sir Kenneth Caiman 18 Points from the Keynote Presentation of Sir David Weatherall 20 Section 4 Working group I: Humanities in medical undergraduate education Key points from the Background Working Paper prepared by Group Chairman Professor Michael Baum 24 Writing as a reflective practitioner. Gillie Bolton 39 Notes from Professor Michael Baum's introductory conference presentation 44 Conclusions and recommendations from Group I 47 CONTENTS Section 5 Working group II: Humanities in community development and health Key points from the Background Working Paper prepared by Group Chairman Reverend Andrew Mawson 53 Notes from Reverend Mawson's introductory conference presentation 68 Conclusions and recommendations from Group II 70 Section 6 Working -

Analysis of Research and Education Indicators to Support Designation of Academic Health Science Centres in England

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public INFRASTRUCTURE AND service of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND TERRORISM AND Browse Reports & Bookstore HOMELAND SECURITY Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Europe View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Errata To: Recipients of RR-318-DH, Analysis of research and education indicators to support designation of Academic Health Science Centres in England From: RAND Corporation Publications Department Date: May 2013 Re: Corrected pages (pp. -

Providing a 21 Century Facility for Moorfields Eye Hospital

Providing a 21st century facility for Moorfields Eye Hospital Involving patients and the public Tell us what you think Version: 1 Published: November 2013 1 Contents Section Page 1 Introduction 2 2 Our vision for the new facility 3 3 Background to the engagement exercise 3 4 Why we want to move 4 5 Why King’s Cross/Euston? 5 6 What we are engaging about 6 7 How you can have your say 7 8 What happens next 7 9 Further information 7 10 Tell us what you think 8 2 1. Introduction This document outlines a proposal by Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust to move our main central London hospital from City Road near the Old Street roundabout to more modern facilities in the King’s Cross/Euston area. We plan to do this in partnership with our research colleagues at the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology. We need a new facility for several reasons: • Our existing buildings in City Road are more than 100 years old and were built at a time when hospital care was provided very differently to how it is now – they are no longer suited to the provision of 21st-century clinical care, research or education • Our ageing infrastructure is growing increasingly difficult and costly to maintain • The configuration of our existing buildings offers little scope for true integration between the clinical, research and teaching elements of our work, which will be crucial if we are to achieve our vision for the future (see section 2 below) • Although intermediate refurbishments go some way to improving the environment for our patients and staff, they are no substitute for purpose-built accommodation An in-principle decision to focus all our efforts on moving, rather than trying to rebuild on our current campus, was taken by our board of directors in March 2013, following an extensive options appraisal. -

14Th Floor, Euston Tower 286 Euston Road London NW1 3DP Wednesday 22Nd May 2019 Sent Via Email: To: Local A

14th Floor, Euston Tower 286 Euston Road London NW1 3DP www.camdenccg.nhs.uk Wednesday 22nd May 2019 Sent via email: To: Local Authority Health Overview and Scrutiny Chairs CC: Council Leaders Dear colleague, RE: Public consultation on the proposed move of Moorfields Eye Hospital’s (City Road, London) services The NHS in north central London is working with NHS England Specialised Commissioning, in partnership with Moorfields Eye Hospital, University College London and Moorfields Eye Charity, on a proposal to bring together services from Moorfields’ main City Road hospital site and the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology in a new purpose-built centre. Following my previous correspondence with you on 28 March 2019 we are now writing to you, in partnership with your local CCG partners, to announce the launch of a public consultation on the proposal, running between 24 May and 16 September 2019. This consultation is being carried out pursuant to the clinical commissioning groups’ (CCGs) legal duties to involve the public under s.14 Z 3 of the National Health Service Act 2006 and to consult with relevant local authorities under regulation 23 Local Authority (Public Health, Health and Wellbeing Boards and Health Scrutiny) Regulations 2013. The proposal was approved for public consultation by the Moorfields Consultation programme board on 15 May 2019. This followed meetings of the London Regional Team for NHS England Specialist Commissioning Services, and then the Committees in Common of the 14 clinical commissioning groups who hold contracts with Moorfields, which took place in April 2019. Both groups considered supporting documentation and assurance in relation to the proposals, and feedback from the North Central London (NCL) JHOSC. -

North London PARTNERS in Health and Care Page | 1 14Th Floor, Euston Tower 286 Euston Road London NW1 3DP T

14th Floor, Euston Tower 286 Euston Road London NW1 3DP www.camdenccg.nhs.uk Thursday 13 February 2020 Sent via email: Dear colleague Proposed move of Moorfields Eye Hospital’s City Road services The proposal to move Moorfields Eye Hospital, University College London’s Institute of Opthalmology and Moorfield’s Charity to a new site at St. Pancras in London has been approved. Camden Clinical Commissioning Group on behalf of those CCGs across England that commission services from Moorfields City Road site, in partnership with NHS England/Improvement Specialised Commissioning (London), consulted between 24 May and 16 September 2019 on a proposal to relocate services from Moorfields Eye Hospital’s City Road site to St Pancras. This new-build centre will bring together excellent eye care, ground-breaking research and world- leading education in ophthalmology. This project will be a partnership between Moorfields Eye Hospital and University College London (UCL) Institute of Ophthalmology (IoO). Moorfields Eye Hospital and UCL will sell the current land at City Road, and all proceeds of the sale will be reinvested in a multi-million pound development on land available at the site of St Pancras Hospital, just north of King’s Cross and St Pancras stations in central London. During the consultation around 4,600 contributions were received, of which 1,511 were completed consultation surveys. People also gave their feedback in other ways including emails, discussion groups, phone calls, letters and via the virtual assistant on the consultation’s website. You can read the final outcome report at https://oriel-london.org.uk/consultation-documents/ . -

Job Title: Clinical Fellow (ST7+) - Neuro-Ophthalmology

Job title: Clinical Fellow (ST7+) - Neuro-Ophthalmology Division: Queen Square Board/corporate function: Specialist Hospital Board Salary band: MN37 Responsible to: Lead Consultant in Department of Neuro-Ophthalmology Accountable to: Divisional Clinical Director Hours per week: Full Time, 40 hours per week Location: National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH) is one of the most complex NHS trusts in the UK, serving a large and diverse population. We provide academically-led acute and specialist services, to people from the local area, from throughout the United Kingdom and overseas. Our vision is to deliver top-quality patient care, excellent education and world-class research. We provide first-class acute and specialist services across eight sites: University College Hospital (incorporating the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Wing) National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital Eastman Dental Hospital Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine University College Hospital Macmillan Cancer Centre The Hospital for Tropical Diseases University College Hospitals at Westmoreland Street We are dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of many complex illnesses. UCLH specialises in women’s health and the treatment of cancer, infection, neurological, gastrointestinal and oral disease. It has world class support services including critical care, imaging, nuclear medicine and pathology. National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery – Queen Square The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (NHNN), Queen Square is an internationally renowned specialist hospital within UCLH Trust. The NHNN is the UK's largest dedicated neurological and neurosurgical hospital providing comprehensive inpatient and outpatient services for the diagnosis, treatment and care of all conditions that affect the brain, spinal cord, peripheral nervous system and muscles. -

Buses from Old Street and Moorfields Eye Hospital

Friern Barnet Library 43 Buses from 141 Palmers Green North Circular Road N55 Colney Hatch Lane 76 continues to Old Street and Lordship Tottenham Wanstead , Lane Bruce Grove Hale South Woodford Moorfields Eye Hospital Muswell Hill Broadway 243 and Woodford Wells Wood Green Tottenham Town Hall Highgate Whipps Cross Turnpike Lane Archway Seven Sisters 214 Highgate 55 Leyton Baker’s Arms for Whittington Holloway Harringay Green Lanes 271 Hill Hospital Nag’s Head Stamford Hill Broadway Lea Bridge Road Manor House Highgate Upper Village Holloway Stoke Newington Clapton Holloway 21 Newington Green Lea Bridge Roundabout Parliament Hill Fields Road Dalston Kingsland Mildmay Park 394 Dalston Junction Kentish Town Highbury & Islington Englefield Road Homerton Hospital Essex Road Southgate Road Camden Town Islington Northchurch Road Hackney 394 St Mary’s Church Haggerston Downs Islington New North Kingsland Road Mornington Tolpuddle Street Road Hoxton Baring Street Hackney Crescent Central New North Road Crondall Hoxton Broadway St Pancras International Mintern Street and King’s Cross Street Kingsland Road Market W S W Baker Street T H B Mare Street E A for Geffrye Pancras Road W Warren E EP R for Madame RRA T L L Well Street for E I L K E T H ST ES Museum W A Paddington Tussaud’s Street S E C E London Fields N L E L R R E A N C D T I Y N T I D Y E A U S D I R S R N O A S WALK T O G P D D Marylebone Great Euston Euston St Pancras King’s Pentonville Islington A L L S E A D A Cambridge 205 C Y Q O Angel E T O Leyton Portland Square International Cross Road . -

Letter-From-Moorfields-Hes.Pdf

Moorfields at City Road 162 City Road London EC1V 2PD Tel: 020 7253 3411 29th January 2020 Dear Optometrists, 1. Moorfields A&E has seen a significant rise in patients being sent from community optometrists, often from very long distances, where closer emergency ophthalmic provision is available. In many cases, patients are sent to A&E without any discussion or referral letter. An internal audit revealed that 40% of emergency referrals to A&E do not require an A&E attendance. 2. We have also seen a large rise in Optometrist referrals (GOS-18) to GPs asking for 1-2 week appointments which GPs are unable to obtain. These patients are frequently sent to A&E, which then doubles the cost to CCGs (as the A&E attendance and subsequent clinic review are both charged for separately). Such cases are usually inappropriate for A&E review. Should you need to make such a request, please do not send them to A&E. It is usually better to telephone your local eye unit and ask for the most appropriate pathway for the patient (e.g. AMD, Glaucoma Pathway etc). 3. As it is local CCGs who foot the bill for such attendances, we will need to feedback directly to them. Please remember that A&E is for genuine and potentially sight threatening emergencies only. 4. We have also seen an increase in patients being sent to us while already under the care of other units requesting second opinions. We do not offer second opinions in the A&E department, and as such, patients will be reverted back to the original referrer. -

First RLUK Conference

rluk research libraries uk rluk research libraries uk rluk research libraries uk rluk research libraries uk www.rluk.ac.uk www.rluk.ac.uk RLUK Research Libraries UK RLUK Research Libraries UK RLUK Research Libraries UK RLUK Research Libraries UK First RLUK Conference: The Power of Knowledge First RLUK Conference: The Power of Knowledge Wednesday 22nd October 12 noon Registration Weetwood Hall 13:00-14:00 Lunch Woodland Suite Day 1: The changing landscape of UK research universities Chair: Margaret Coutts 14:00-14.:45 Keynote speaker: Sir Drummond Bone ‘The changing context of UK HE research 2008-2013’ 14:45-15:00 Tea and coffee Headingley Suite 15:00-16:45 Plenary session Professor Ewan McKendrick (University of Oxford) ‘The Research Excellence Framework and the future of metrics’ Professor Teresa Rees (Cardiff University) ‘A University’s Research Strategy: Preparing for the future’ Steve Scott (University of Leeds) ‘The changing context of research and its impact on research students 2008-2014’ David Sweeney (HEFCE) 17:45 Coaches to Brotherton Library 18:00-19:45 Drinks reception, Art Gallery, Brotherton Library Sponsored by JISC 19:40 Coaches to Weetwood Hall 20:00 Dinner, Woodland Suite, Weetwood Hall Thursday 23rd October Day 2: RLUK’s strategy and engagement for the next five years Chairs: Sheila Cannell/Phil Sykes 9:00 Registration 9:15 Tea and coffee Headingley Suite 9:30-10:00 Introduction: Mark Brown, Chair RLUK ‘Future-gazing: Strategic directions for RLUK in the next five years’ 10:00-13:00 Plenary session Chair: Sheila Cannell