Stress-Reducing Function of Matcha Green Tea in Animal Experiments and Clinical Trials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TSUCHIKURA Product Description ◆Japanese Green Tea Powder 50 - Fuji Cans

TSUCHIKURA Product Description ◆Japanese Green Tea Powder 50 - Fuji Cans Price \1000 (plus tax) Product Description This is an instant type of sweetened green tea. back This tea can be used to make Latte or in baking. The stylish packaging of World Heritage site Mount Fuji also makes a pleasing gift. Only Japanese green tea is used to make this product. ◆Japanese Tea containing Matcha Green Tea in Orchid-shaped cans 80g Price \1000 (plus tax) Product Description This is a mild flavored Japanese Tea with Green Matcha Tea. The stylish packaging also makes a pleasing gift. The Meiji era export label design has an orchid shape. The two types of packaging are an emerald green crane and vermilion Maiko girls. Ranjikan was awarded 2nd place in The 24th Seal and Label Contest. (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Commerce and Information Policy Bureau Director Award) ◆Japanese Teabags with Hokkaido Matcha Green Tea - Pack of 6 bags Price \500 (plus tax) Product Description This is a tea bag with Matcha green tea that gives a tradidional Japanese feeling. There are 2 types of packaging, All Hokkaido and Regional Hokkaido. This is ideal as a gift or souvenir from Hokkaido. ◆Hokkaido Tea Selection TB / 5 bag set Price OPEN Product Description The green tea is also carefully selected and only Japanese green tea is used. High quality Tetra type tea bags are used to give a full-fledged flavor. Other flavors available are Rugosarose, mint and corn and lavender. ◆Hokkaido Barley Tea TP / 10 bag set Price \370 (plus tax) Product Description With Okhotsk certification mark! Cute illustrations that the image of a ice floe. -

MATCHA 2018 • FLAVOR INSIGHT REPORT Matcha, Also Referred to As Hiki-Cha, Is a Finely Ground Powder of Specially Grown and Processed Green Tea Leaves

MATCHA 2018 • FLAVOR INSIGHT REPORT Matcha, also referred to as hiki-cha, is a finely ground powder of specially grown and processed green tea leaves. Traditionally, Japanese tea ceremonies center on the preparation, serving, and drinking of matcha. The hot tea is said to embody a meditative spiritual style. Today, matcha is also used to flavor and dye foods such as mochi and soba noodles. We’re seeing this unique taste appear in a plethora of products and recipes, from a squid ink noodle dish to flavored almond milk. Let’s take a look at the various forms of matcha green tea on the menu, in social media, and in new products. On the Food Network, 70 MATCHA recipes appear in a search Print & Social Media Highlights for matcha. Recipes include matcha blondies, matcha There are several mentions of matcha in social and print media. Here are lemonade, matcha herb some of the highlights. 70 scones, coconut matcha- cream pie, matcha steamed • While scrolling through Pinterest, matcha pins appear in a wide MATCHA RECIPES variety of food and beverage recipes, especially beverages and baked cod, no-churn matcha ice ON FOOD NETWORK goods. These pins include iced coconut matcha latte, matcha no- cream, matcha roast chicken bake energy bites, matcha chocolate bark, matcha chia pudding, with leeks and matcha and matcha overnight oats, and matcha banana donuts with matcha mushroom soup. lemon glaze. • A Twitter search shows tweets mentioning matcha, a linked recipe from @ArgemiroElPrimo for “homemade matcha green tea muffins with matcha glaze.” Also mentioned by @LeilaBuffery: a recipe for “vegan matcha green tea cake” with linked video tutorial. -

Tea Components

Tea Components The differences of varieties, the environmental Composition of fresh tea leaves effects, various methods of processing and modes of propagations cause the change of chemical � Polyphenol composition of tea leaves. As shown in the figure on the right, the composition of fresh tea flush contains various components, such as polyphenol (include catechins),caffeine,amino acids, vitamins,flavonoids, Insoluble� components polysaccharides and fluorine. Structural formulae of Polysaccharides� catechins, caffeine, theanine, saponins as main green Proteins� tea componets are drawn in the figure below. Pigments Polyphenols and caffeine are the most important Caffeine chemicals of tea, considerable pharmacological Amino acids significance. Polyhenols are present to the extent of Carbohydrates 30-35 % in the dry tea leaf matter and their content determines the quality of the beverage. Ash Structural formulae of green tea components Catechins Caffeine Tea leaf saponins (-)-Epicatechin :R1=R2=H (-)-Epigallocatechin :R1=H, R2=OH (-)-Epicatechin gallate :R1=X, R2=H (-)-Epigallocatechin gallate :R1=X, R2=OH Theanine Barringtogenol C :R1=R2=CH3, R3=OH, R4=H Camelliagenin A :R1=R2=CH3, R3=R4=H A1-barrigenol :R1=R2=CH3, R3=H, R4=OH R1-barrigenol :R1=R2=CH3, R3=R4=OH Japanese Green Tee Chemical Composition of Various Kinds of Japanese Green Tea Chemical composition of Gyokuro, Sencha, that of Matcha, Gyokuro and Hojicha is poor. Kamairicha, Bancha, Hojicha and Matcha is shown in Ascorbic acid content of Sencha, Bancha and the table below. Matcha, Gyokuro and Sencha are Kamairicha is high, but of Gyokuro and Hojicha is rich in total nitrogen, whereas Bancha and Hojicha are low. -

Inspiring Conscious Living and Spreading Simplicity

w We focus on plant based food choosing Inspiring mainly seasonal ingredients, organic and locally sourced. conscious living and spreading Curious about the farmers behind our teas? We have some stories to share with simplicity… you, feel free to ask or check our website. Just one cuppa at a time! Menu i love you so matcha! MENU @GOODTEASTORIES Follow us on Instagram WIFI : Yksi Expo | YksiWiFi Illustration Anna Lena | Graphic design Aurore Brard Served hot Vegan FOOD DRINKS Served cold DRINKS BREAKFAST LOOSE LEAF TEA OUR FAVORITES CHIA JAR 5.00 GREEN TEA 3.00 Our vegan High tea 20 /p Chia seeds, plant based milk, jam, agave syrup, granola. Bancha | Japan Selection of 4 different kind of tea paired with vegan cakes, Ceremonial matcha (+2.00) | Japan seasonal fruits, vegan yogurt bowl and assortments of toasts. PROTEIN TOAST* 4.50 Dragon well | China Hand-made dates peanut butter, banana, cacao nibs Gold hojicha | Japan Summer special: watermelon matcha iced tea 4.50 Kabuse sencha (+1.00) | Japan GRANOLA BOWL 6.00 Kukicha | Japan Blue tea matcha lemonade 4.50 Soy yoghurt, granola, hand-made salted caramel peanut Popcorn tea | Japan butter, cacao nibs. Sencha of the wind | Japan Sakura flowers | Japan 4.00 REAL ACAI BOWL 8.50 Signature ice tea 4.00 Acai pulp, granola, seasonal fruits, toasted coconut chips, OOLONG TEA 3.00 Our dragon well green tea, ginger, lime, lemongrass CLUB cacao nibs, chia seeds, agave syrup. Iron goddess | China soda, passion fruit. 3.00 BLACK TEA Tea gourmand 6.00 SNACK/LUNCH Golden monkey | China Your selection of tea served with different little sweet bites. -

Umami Café by AJINOMOTO CO

Umami Café BY AJINOMOTO CO. The Tea Experience For centuries, green tea has been treasured throughout Asia for its healthful, restorative qualities. In Japan, Zen priests drank green tea to keep them awake through long hours of meditation. In the 16th century, a man named Sen no Rikyù, influenced by the study of Zen, envisioned a path to enlightenment through the simple act of sharing a bowl of tea among friends in the spirit of peace and harmony—a practice he called wabi-cha. For Rikyu, making tea while mindfully engaging all the senses was to have a complete Zen experience. We are pleased to have you share a moment of quiet joy with us and experience the spirit of Japanese culture through a simple bowl of tea. Tea Sets We’ve paired traditional teas with Japanese sweets. A great place to start. Matcha with Hanabira Mochi GF V $14 Sencha with Fried Rice A bowl of hand-whisked, jade green matcha is paired with a traditional Japanese tea ceremony sweet. Tender sheets of mochi rice dough The light, sweetness of our Sencha balances nicely with the strong umami flavors of either our Yakitori Chicken Style Fried Rice ($14) or our are folded over candied burdock root and filled with sweetened white bean paste infused with a hint of miso. Takikomi Gohan Style Vegetable Fried Rice V ($12). Additional tea steepings available upon request. Sencha with Castella Cake $12 Matcha with Mochi Ice Cream GF $12 Genmaicha with Manju $11 Hojicha with Shortbread Cookies $9 The light, mild sweetness of the Sencha is enhanced by this A bowl of our hand-whisked matcha is paired with a premium Genmaicha, with its roasted rice and earthy flavor, is a perfect These bitter chocolate and vanilla cookies highlight the aromatic popular Japanese sponge cake. -

IKKYU Brochure 2017

PREMIUM JAPANESE GREEN TEA 煎 茶 道 EXCLUSIVELY FROM KYUSHU YOUR BEST CHOICE FOR GREEN TEA IN JAPAN IKKYU G.K. / Noke 8-29-7 / Sawara-ku / Fukuoka city / Japan 814-0171 IKKYU - PREMIUM JAPANESE GREEN TEA / 2 Kyushu Land of Exceptional Green Teas Our green tea comes exclusively from Kyushu, the south- western island of Japan, more than 1’000 km south of Tokyo. It is a lush and vibrant place, with a warm and humid climate. IKKYU green tea is grown in six Kyushu prefectures: Fukuoka (Yame), Nagasaki (Higashi Sonogi), Saga (Ureshino) Kumamoto, Miyazaki and Kagoshima (Chiran). Tea fi elds are nested in alti tude between mountains, on lower plains or by the sea. A wide range of soils and climate conditi ons gives birth to extraordinary and diverse green teas, using lesser known culti vars that yield a sweeter tea. HONSHU KYOTO OSAKA KYUSHU FUKUOKA SHIKOKU IKKYU - PREMIUM JAPANESE GREEN TEA / 3 IKKYU Tea Partners IKKYU has built a strong network of small and medium- sized tea farmers who produce only premium green teas. We collaborate closely to make them reach the overseas markets. Our teas are traceable and we are delighted to share the stories of the people behind them. Their know-how and skills include traditi onal processing methods that make fragrant and delicious green teas, sti ll unknown outside Japan. The excellence of their hard work is celebrated on a regular basis by presti gious awards and grand prizes, at regional, nati onal and internati onal levels. IKKYU is proud to help them share their wonderful creati ons with tea lovers all around the world. -

Health Benefits of Matcha Green

Health Benefits of Matcha Matcha Green Tea has been consumed for centuries by Buddhist Monks, Samurai Warriors, and millions of the Japanese population. The reason they keep drinking it is because of all the amazing health benefits it provides simply by drinking it once a day. The green tea leaf is world-renowned for it's weight loss benefits, antioxidant content, energy boosting properties, and much more. However, the regular way of brewing green tea, which is merely soaking the leaves in hot water, and then discarding them, does not do justice to the benefits of this amazing plant. Matcha Green Tea is a fine powdered form of shade grown green tea leaves. This means you consume the entire leaf and your body can benefit from all of its nutritional properties. Premium grades of matcha contain only the finest green tea leaves in the world. They undergo the most careful and meticulous growing, harvesting, and preparation procedures that have been passed down by generation. Source: Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, Lipophillic and Hydrophillic Antioxidant Capacities of Common Foods in the US. Antioxidant Powerhouse Antioxidants are naturally occurring chemicals in food that help your body fight diseases, prevent aging, and ensure your body is operating at it's peak potential. When it comes to natural antioxidant content, matcha is at the top of the list. The ORAC value (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity) measures the amount of antioxidants per serving of a given food. Matcha Green tea contains an incredible 1384 units of antioxidants -- 14x the antioxidants of blueberries, and 6x the antioxidants of dark chocolate. -

Matcha Green Tea: Scientific Name- Camellia Sinensis

Matcha Green Tea: scientific name- Camellia sinensis Tea has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for over 5000 years. Writings from the Tang Dynasty indicate that by 650 AD tea was cultivated throughout China. It was introduced to Japan in about 600 AD by Buddhist priests returning from study in China. The legendary health benefits of tea have been evaluated by modern science. This information is so well known and so thoroughly documented that I will not go into great detail in this product brief. Evidence- based scientific studies are documented in the end notes. Polyphenols function as powerful antioxidants. One of the most powerful antioxidants found in green tea is Epigallocacatechin Gallate. EGCG may help against free radicals that contribute to can- cer(1), heart disease and clogged arteries (2). They are also helpful to burn fat (3) and counteract oxidative stress in the brain that can lead to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s (4). Weight Management: EGCG inhibits enzymes that break down the hormone norepinephrine. Increasing norepinephrine levels increase the signals that stimulate the body to breakdown fat – especially visceral fat that builds up around our organs in the abdominal area. In addition caffeine stimulates fat burning by increasing our metabolic rate. The overall effect is weight loss and energy gain. (8) (See also footnotes #3) Physical and Cognitive Stimulation: Tea contains caffeine which blocks adenosine receptors and inhibits the effects of adenosine. The caffeine binds to and occupies the adenosine receptor sites. However, caffeine doesn't slow down the cell's activity as adenosine would. -

Onodera Ochakai Japanese Afternoon Tea Afternoon Tea 27.5

ONODERA OCHAKAI JAPANESE AFTERNOON TEA AFTERNOON TEA 27.5 In association with A choice of one tea 35 OCHAKAI JAPANESE TEA CEREMONY SPIDER ROLLS スパイダーロール A choice of two teas with matcha prepared on the table Deep fried crab rolls with spicy sauce WAGYU SLIDERS COCKTAILS 35 和牛バーガー Premium Wagyu beef sliders A choice of any cocktail SALMON TATAKI サーモンのたたき CHAMPAGNE One glass 38 Lightly seared salmon with plum & cucumber dressing Bottomless 70 CRAB CROQUETTES 蟹クリームコロッケ Deep fried croquettes with homemade bechamel sauce BEEF TERIYAKI Tsujiri was founded in 1860 by Mr Riemon Tsuji in Uji, Kyoto. Using advanced techniques and storage methods, he strived to make the highest quality green tea. His legacy lives onto today and is widely 牛肉の照り焼き commemerated as establishing Uji tea's popularity not only in Japan but the whole world. Grilled sirloin beef accompannied with seasonal vegetables CHICKEN KARAAGE 地鶏の唐揚げ TEA SELECTION Lighly battered fillets served with lemon and sundried chillies KINAKO BLANCMANGE KABUSECHA かぶせ茶 きなこブランマンジェ Tea leaves covered for 10 days to give an elegant sweetness. Soy bean blanmange with black sugar syrup SENCHA 煎茶 CHOCOLATE GÂTEAU Steamed & rolled tea leaves. Refreshing and balanced チョコレートガトー HōJICHA ほうじ茶 Served with mochi icecream and matcha sauce Roasted green tea leaves. Smokey and nutty. GENMAICHA 玄米茶 Tea leaves mixed with brown rice. Buttery with a nutty aroma. MATCHA 抹茶 Beautiful aroma with a touch of sweetness. Please ask your server for information on allergens A discretionary 12.5% service charge will be added to your bill A selection of teas and herbal teas are available on request HIGH TEA 11 A choice of one tea with Two desserts from below MATCHA PARFAIT 抹茶パフェ Home made matcha ice cream topped with fruits and matcha cake. -

White Microwave Mochi Makes 7-8 Pieces

White Microwave Mochi makes 7-8 pieces Ingredients: ● 1 cup mochiko flour ● 1 cup water ● 1/2 cup sugar ● For dusting and shaping mochi: ½ cup cornstarch or potato starch Optional flavorings: 1 tsp matcha for matcha mochi OR 1 tsp rosewater plus 1 drop red food coloring for rosewater mochi Optional fillings: ● Nutella, refrigerate the jar for 1 hour before using ● Sweet red bean paste in a bag (buy at Japanese or Asian store) ● Fresh sliced fruit ● Peanut butter ● Chocolate chips (white and/or semi-sweet) Directions: 1. Mix all ingredients together well, and put in a medium-size microwaveable bowl( glass or ceramic bowl works). If adding matcha or another flavoring powder, make sure to mix it thoroughly with the mochiko flour before adding the wet ingredients. 2. Microwave the bowl, uncovered, on high for 2 minutes. Stir the mixture thoroughly with a rice paddle or spatula. 3. Microwave the mixture again for another 2 minutes. Meanwhile, dust your cutting board with about ¼ cup of cornstarch or potato starch. Mix the mochi in the bowl thoroughly, and scoop the mochi mixture out in one mass, laying it onto your starch-covered board. Let the mochi cool for 5 minutes. Cover your hands with starch and then carefully reach under the mochi, and flip the whole mass onto the other side. This is to make sure the mochi is completely covered with starch. 4. Form the mochi into a 3-inch wide log. Pinch off golf-ball size pieces using your left hand to pinch and your right hand to pull the mochi away from the log. -

Organic Product List (PDF)

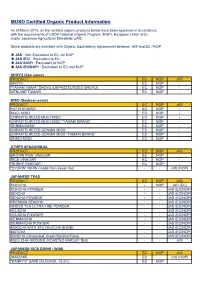

MUSO Certified Organic Product Information As of March 2015, all the certified organic products below have been approved in accordance with the requirements of USDA National Organic Program (NOP), European Union (EC), and/or Japanese Agricultural Standards (JAS). Some products are available with Organic Equivalency Agreements between JAS and EC / NOP. JAS : Non-Equivalent to EC nor NOP JAS (EC) : Equivalent to EC JAS (NOP) : Equivalent to NOP JAS (EC/NOP) : Equivalent to EC and NOP SHOYU (Soy sauce) PRODUCT EC NOP JAS SHOYU EC NOP - "YAMAKI NAMA" SHOYU (UNPASTEURIZED SHOYU) EC NOP - GENUINE TAMARI EC NOP - MISO (Soybean paste) PRODUCT EC NOP JAS HATCHO MISO EC NOP - MUGI MISO EC NOP - UNPASTEURIZED MUGI MISO EC NOP - UNPASTEURIZED MUGI MISO "YAMAKI BRAND“ EC NOP - GENMAI MISO EC NOP - UNPASTEURIZED GENMAI MISO EC NOP - UNPASTEURIZED GENMAI MISO "YAMAKI BRAND“ EC NOP - SHIRO MISO EC NOP - OTHER SEASONINGS PRODUCT EC NOP JAS BROWN RICE VINEGAR EC NOP - RICE VINEGAR EC NOP - "SUSHI" VINEGAR EC NOP - "SYURIN" MIRIN (made from sweet rice) - - JAS (NOP) JAPANESE TEAS PRODUCT EC NOP JAS KUKICHA - NOP JAS (EC) KUKICHA POWDER - - JAS (EC/NOP) SENCHA - - JAS (EC/NOP) SENCHA POWDER - - JAS (EC/NOP) PREMIUM SENCHA - - JAS (EC/NOP) GREEN TEA ULTRA FINE POWDER - - JAS (EC/NOP) HOJICHA - - JAS (EC/NOP) HOJICHA POWDER - - JAS (EC/NOP) GENMAICHA - - JAS (EC/NOP) GENMAICHA POWDER - - JAS (EC/NOP) KUKICHA WITH 20% HOJICHA BLEND - - JAS (EC/NOP) MATCHA - - JAS (EC/NOP) BANCHA (Unroasted, Green Bancha Flake) - - JAS (EC/NOP) MUGI CHA-GROUND (ROASTED BARLEY -

Brewing Instructions

Do we believe in karma? Magic? Santa Claus? We’re not quite sure... but we do believe in the Brewing hustle. It’s the backbone of our business, and responsible for MatchaBar’s very existence! The hustle is about going above and beyond to get the job done. Our community, the MatchaFam, Instructions Denes itself by just this - hard work, passion, and a sense of purpose. What you’ll need 1 tsp (1.5-2 g) MatchaBar matcha green tea powder Matcha tea 1 cup almost boiling or cold water 1 Scoop or sift the matcha powder into your cup. The whisk Option 1 Electronic Aerolatte whisk - 2 Add 1/2 cup of hot or cold water. originally intended for frothing cold milk, this is our tool of choice to make 3 Whisk until the matcha powder the perfect matcha at home. has fully dissolved and a thin layer of foam forms on the top. Option 2 Traditional bamboo whisk - this tool has been used during tea 4 Pour another 1/2 of hot or cold ceremonies for centuries in Japan and water into your cup and give it a quick stir. is still used across the world. Optional Sifter an extra sift helps to Optional Add sweetener or spice if thats what you’re into. create a ner powder. A ner powder makes for a smoother cup of matcha. Drink and Enjoy! The Mid-Matcha Shake When drinking your iced matcha, don’t hesitate to perform the classic mid-matcha shake if you see the powder begin to settle.