F. Trollope, Dickens, Irving and Parkman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corso Di Dottorato Di Ricerca Storia E Cultura

DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE UMANISTICHE, DELLA COMUNICAZIONE E DEL TURISMO (DISTUCOM) CORSO DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA STORIA E CULTURA DEL VIAGGIO E DELL’ODEPORICA IN ETA’ MODERNA – XXIV Ciclo. ‘EXPEDITION INTO SICILY’ DI RICHARD PAYNE KNIGHT: ESPERIENZE DI VIAGGIO DI UN ILLUMINISTA INGLESE DI FINE SETTECENTO Sigla del settore scientifico-disciplinare (M.STO/03) Coordinatore: Prof. Gaetano Platania Firma ……………………. Tutor: Prof. Francesca Saggini Firma ……………………. Dottoranda: Olivia Severini Firma ……………………. “Questo Payne Knight era uomo di forte intelletto.” Ugo Foscolo, 1825 I N D I C E Pag. Indice delle illustrazioni 1 Introduzione 2 Capitolo primo - Traduzione con testo inglese a fronte 7 Capitolo secondo - L'autore, l'argomento e la storia del manoscritto 2.1 Notizie sulla vita e le opere di Richard Payne Knight 50 2.2 Il lungo viaggio di un diario di viaggio 65 Capitolo terzo - Il contesto del viaggio di Knight 3.1 Il contesto storico: dall’Inghilterra alla Sicilia 94 3.2 Il contesto filosofico: l’Illuminismo inglese e il pensiero di Knight 106 3.3 Il contesto artistico: alla riscoperta dei classici tra luci ed ombre 120 3.4 Il contesto scientifico: il problema del tempo nel settecento 134 3.5 Il Grand Tour nella seconda metà del Settecento 148 Capitolo quarto - L’analisi del testo e il pensiero di Knight 4.1 Analisi del testo della Expedition into Sicily 169 4.2 Gli stereotipi sull’Italia 215 Conclusioni 226 Bibliografia 230 I N D I C E D E L L E I L L U S T R A Z I O N I Pag. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

INSTITUTIONALISING the PICTURESQUE: the Discourse of the New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects

INSTITUTIONALISING THE PICTURESQUE: The discourse of the New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture at Lincoln University by Jacky Bowring Lincoln University 1997 To Dorothy and Ella iii Abstract of a thesis submitted in fulfIlment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture INSTITUTIONALISING THE PICTURESQUE: The discourse of the New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects by Jacky Bowring Despite its origins in England two hundred years ago, the picturesque continues to influence landscape architectural practice in late twentieth-century New Zealand. The evidence for this is derived from a close reading of the published discourse of the New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects, particularly the now defunct professional journal, The Landscape. Through conceptualising the picturesque as a language, a model is developed which provides a framework for recording the survey results. The way in which the picturesque persists as naturalised conventions in the discourse is expressed as four landscape myths. Through extending the metaphor of language, pidgins and creoles provide an analogy for the introduction and development of the picturesque in New Zealand. Some implications for theory, practice and education follow. Keywords picturesque, New Zealand, landscape architecture, myth, language, natural, discourse iv Preface The motivation for this thesis was the way in which the New Zealand landscape reflects the various influences that have shaped it. In the context of landscape architecture the specific focus is the designed landscape, and particularly the perpetuation of design conventions. Through my own education at Lincoln College (now Lincoln University) I became aware of how aspects of the teaching of landscape architecture were based on uncritically presented design 'truths'. -

The Shropshire Enlightenment: a Regional Study of Intellectual Activity in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries

The Shropshire Enlightenment: a regional study of intellectual activity in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries by Roger Neil Bruton A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham January 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The focus of this study is centred upon intellectual activity in the period from 1750 to c1840 in Shropshire, an area that for a time was synonymous with change and innovation. It examines the importance of personal development and the influence of intellectual communities and networks in the acquisition and dissemination of knowledge. It adds to understanding of how individuals and communities reflected Enlightenment aspirations or carried the mantle of ‘improvement’ and thereby contributes to the debate on the establishment of regional Enlightenment. The acquisition of philosophical knowledge merged into the cultural ethos of the period and its utilitarian characteristics were to influence the onset of Industrial Revolution but Shropshire was essentially a rural location. The thesis examines how those progressive tendencies manifested themselves in that local setting. -

Collecting the World

Large print text Collecting the World Please do not remove from this display Collecting the World Founded in 1753, the British Museum opened its doors to visitors in 1759. The Museum tells the story of human cultural achievement through a collection of collections. This room celebrates some of the collectors who, in different ways, have shaped the Museum over four centuries, along with individuals and organisations who continue to shape its future. The adjoining galleries also explore aspects of collecting. Room 1: Enlightenment tells the story of how, in the early Museum, objects and knowledge were gathered and classified. Room 2a: The Waddesdon Bequest, displays the collection of Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces left to the British Museum by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild MP at his death in 1898. Gallery plan 2 Expanding Horizons Room 1 Enlightenment Bequest Waddesdon The Room 2a 1 3 The Age Changing of Curiosity Continuity 4 Today and Tomorrow Grenville shop 4 Collecting the World page Section 1 6 The Age of Curiosity, 18th century Section 2 2 5 Expanding Horizons, 19th century Section 3 80 Changing Continuity, 20th century Section 4 110 Today and Tomorrow, 21st century Portraits at balcony level 156 5 Section 1 The Age of Curiosity, 18th century Gallery plan 2 Expanding Horizons 1 3 The Age Changing of Curiosity Continuity 4 Today and Tomorrow 6 18th century The Age of Curiosity The Age of Curiosity The British Museum was founded in 1753 as a place of recreation ‘for all studious and curious persons’. Its founding collection belonged to the physician Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753). -

University Microfilms 300 North Zaeb Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Newsletter, Spring 2016

Newsletter, Spring 2016 The NDAS AGM, March 2016: At the annual general meeting of the society held in March 2016 Linda Blanchard was re-elected to lead the Society for the year 2016-17. We thank Linda for accepting the role once again and look forward to another year under her chairmanship. Alison Mills was re-elected as Vice-Chair, John Bradbeer as Secretary and Bob Shrigley as Treasurer and Membership Secretary. The NDAS Committee was re-elected en bloc. Committee members are: Linda Blanchard (Chair), Alison Mills (Vice-Chair), John Bradbeer (Secretary), Bob Shrigley (Treasurer and Membership Secretary), Pat Hudson (Publicity), Terry Green (Newsletter), Matt Chamings (Barnstaple Town Council), Derry Bryant, Brian Fox, Lance Hosegood, Colin Humphreys (South West Archaeology), Jonathan Lomas, Sarah McRae, Stephen Pitcher, Chris Preece. Your main contacts are: Linda Blanchard: [email protected] 01598 763490 John Bradbeer: [email protected] 01237 422358 Bob Shrigley: [email protected] 01237 478122 Membership Subscriptions: If you haven’t already renewed for the current year, may we remind you that annual subscriptions (£16 per individual adult member, joint membership (couples) £24, junior and student membership £8) became due on 1st April. Subscriptions should be sent to the NDAS Membership Secretary, Bob Shrigley, 20 Skern Way, Northam, Bideford, Devon. EX39 1HZ. You can save yourself the trouble of having to remember every year by completing a standing order, forms available from Bob. FIELDWALKING AT BURYMOOR BRIDGE, HUISH, 15/16 APRIL 2016 The general belief hitherto has been that naturally occurring flint in the north of Devon is restricted to a single clay-with-flints deposit at Orleigh Court near Bideford and otherwise to the beaches, where flint pebbles are found. -

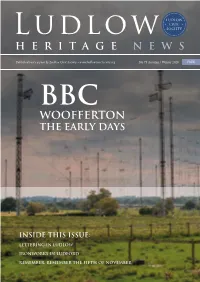

Woofferton the Early Days

Ludlow HERITAGE NEWS Published twice a year by Ludlow Civic Society • www.ludlowcivicsociety.org No 73 Autumn / Winter 2020 FREE BBC WOOFFERTON THE EARLY DAYS INSIDE THIS ISSUE: LETTERING IN LUDLOW IRONWORKS IN LUDFORD REMEMBER, REMEMBER THE FIFTH OF NOVEMBER Ludlow HERITAGE NEWS WOOFFERTON BBC THE EARLY DAYS Very few structures are left in the Ludlow area which can be traced back to the Second World War. However, look five miles south of the town towards the rise of the hills and a tracery of masts can be seen. Go closer, and a large building can be found by the road to Orleton, surrounded now by a flock of satellite dishes, pointing upwards. The dishes are a sign of the recent past, but the large low building was made for the war-time radio station aimed at Germany. This little history attempts to tell the story of the British Broadcasting Corporation’s transmitting station at Woofferton near Ludlow in Shropshire during the first years of its existence. When and why did the BBC appear in the Welsh border landscape with a vast array of masts and wires strung up in the air? The story begins in 1932, when the BBC Empire Service opened from the first station at Daventry in Northamptonshire. Originally, the I think we need to open this edition with an service, to link the Empire by wireless, was intended to be transmitted on acknowledgement of the recent difficult times we long-wave or low frequency. But, following the discovery by radio amateurs that long distance communication was possible by using high frequency or have all been through. -

THE REDISCOVERY of the KNIGHT FAMILY ARCHIVE and ITS IMPORTANCE to EXMOOR Rob Wilson North Introduction and Background at the He

SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS THE REDISCOVERY OF THE KNIGHT FAMILY ARCHIVE AND ITS IMPORTANCE TO EXMOOR Rob Wilson North Introduction and Background family, Richard Payne Knight and Edward Knight At the heart of Exmoor National Park is the former were highly respected collectors and connoisseurs. royal forest of Exmoor. The forest has its origins They have been described as the ‘Light Knight’ in the centuries before the Norman Conquest and and the ‘Dark Knight’ respectively because of the it existed until 1815. During this thousand-year tendency of one to be in the public eye whilst the long period the forest, which comprised open other courted obscurity (Lane 1999); Recognising moorland, was used primarily for livestock grazing their significance certainly enables us to form a in the summer with animals being brought from more balanced view of the Knight dynasty. The nearby and as far away as Tawstock in north Devon family’s interests in agricultural improvement also (around 20 miles) (Siraut 2009). The history of began at this time so that, by the early nineteenth the royal forest, its development, operation and century, their work was described across the county administration has been exhaustively set out by of Worcestershire as ‘spirited cultivation’ (Pitt MacDermot (1911) whose book The History of 1810, xii). John Knight therefore came to Exmoor the Forest of Exmoor is still the key source. More from a practical family of iron masters, notable recently, the Victoria County History produced a connoisseurs and highly respected land improvers. well-received publication series which included He bought Exmoor against a background of success Exmoor – The Making of an English Upland (Siraut and wealth in the west midlands over several M 2009), which provides fresh information on the generations and without any previous direct forest. -

“Functional Picturesque”: Richard Payne Knight and Uvedale Price in Herefordshire’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Brilliana Harley, ‘“Functional Picturesque”: Richard Payne Knight and Uvedale Price in Herefordshire’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XXIV, 2016, pp. 135–158 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2016 ‘Functional PictURESQUE’: RICHARD PAYNE KNIGHT AND UVedale PRICE IN Herefordshire BRILLIANA HARLEY Richard Payne Knight and Uvedale Price pioneered inextricably entwined. Knight, born at Wormsley, a rebellion in landscape design in the late eighteenth grew up as a neighbour to Price at Foxley; they century. These two Herefordshire squires rejected the became friends, began managing their estates at prevalent and popular style of Lancelot ‘Capability’ similar times, and constantly referred to one another Brown, and used the estates they had inherited in letters. Price often informs us of Knight’s activities to stamp their own Picturesque imprint on the and he records Knight being ‘very much fatigued’ by Herefordshire landscape. This article uses Knight’s a Snowdon climb.2 Their published works respond and Price’s writings, together with first-hand to each other, and Knight dedicated The Landscape, observations of a number of other estates and parks in a didactic poem, to Price. Close links with other Herefordshire, to argue that their Picturesque legacy Herefordshire gentry, and their geographical had a far more lasting impact than ‘Capability’ isolation, meant that ideas and practitioners were Brown’s more celebrated influence. It also includes a shared. The Knight family was related to Thomas study of their close involvement in the management Johnes, who lived and carried out improvements and financial organisation of their estates to show at Croft Castle and Hafod (Cardiganshire/Dyfed), that their concept of the Picturesque was both and owned Stanage (Radnorshire/Powys) at one functional and driven by aesthetics. -

SGT Spring 2015

Somerset Gardens Trust A member of the Association of Garden Trusts!! Issue 57 Spring 2015 Featuring Cothay Manor – A private walk into the past The Somerset Gardens Trust From the Editors From the Chairman Spring is in the air. The cold colourless Dear Members, days are fewer and the Sun on bright days The Trust is delighted and honoured that has warmth. So here is the Magazine to the distinguished international Garden encourage you into the garden. There are Designer, Plantswoman and Author, general interest articles on some great Penelope Hobhouse VMH MBE, has historic gardens and Champion Trees in agreed to become one of our Vice- Somerset (one 3000 years old), another Presidents, and we look forward to seeing Members’ ‘My Garden’, starting a her from time to time at our Events. She is Community heritage Apple Orchard and one of the Founder Members of our Trust. much more; there is also a good description of the Trust’s activities – from surveying historic gardens through supporting schools to events – including looking forward to next year’s Cornish Trip organized by the Chairman and John Townson. Meanwhile preparations have started for the Special Party to celebrate the Trust’s 25th Anniversary at Halswell. We are blessed indeed. Christopher and Lindsay Bond [email protected] Somerset Gardens Trust is 25 years old this year and we celebrate our anniversary with a bumper edition of the Magazine in the Summer, and a special Party at Halswell House, Goathurst, Nr Bridgwater, in September. This is a double celebration as eighteen months ago we were extremely concerned about the purchase of Mill Wood. -

Thomas Jones' Langstone Cliff Cottage, Devon

‘The Finest Cradle for Old Age’: Thomas Johnes’ Langstone Cliff Cottage, Devon Diane James Thomas Johnes Esq. of Hafod, Cardiganshire (Figure 1) and his second wife and cousin Jane, purchased Langstone Cliff Cottage near Dawlish, Devon (Figure 2) in 1813, but their change of abode from an extensive estate in the Welsh mountains near Aberystwyth to a Picturesque rustic cottage ornée in Devon can be attributed to a medley of significant events and lifestyle choices. This article examines Johnes’ motives for the abrupt move, and the improvements he Figure 1. William Worthington (c.1795–c.1839), after made to his cottage by the sea. Although living in Devon in Thomas Stothard (1755–1834), Thomas Johnes. the winter months he still retained his Hafod home which Rev. Thomas Frognall Dibdin, The Bibliographical had been designed in a flamboyant Gothic style (Figure 3). Decameron; or, Ten Days Pleasant Discourse upon Johnes had developed the Hafod landscape in a fashionable Illuminated Manuscripts and Subjects Connected Picturesque manner, hoping that the improvements on his with Early Engraving, Typography, and Bibliography, estate showing the latest taste would encourage tourism 3 vols (London: 1817) III, p. 361 to the region, providing work for the local population.1 However, with rising debts through exorbitant spending, and increasing ill-health, Johnes bought Langstone Cliff Cottage as a recuperative sanctuary, to regain his strength whilst also reconciling his debts. His early life had been spent in the erudite pursuit of European art and literary scholarship, which he continued throughout his later life, collecting rare books and mediaeval manuscripts and studying land improvement to enhance both his estate and the lives of his tenants.