Historians and the Lost World of Kansas Radicalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

15/18/22 Liberal Arts and Sciences Political Science Clarence A

The materials listed in this document are available for research at the University of Record Series Number Illinois Archives. For more information, email [email protected] or search http://www.library.illinois.edu/archives/archon for the record series number. 15/18/22 Liberal Arts and Sciences Political Science Clarence A. Berdahl Papers, 1920-88 Box 1: Addresses, lectures, reports, talks, 1941-46 American Association of University Professors, 1945-58 AAUP, Illinois Chapter, 1949-58 Allerton Conference, 1949 Academic freedom articles, reports, 1950-53 American Political Science Association, 1928-38 Box 2: American Political Science Association, 1938-58 American Political Science Review, 1940-53 American Scandinavian Foundation, 1955-58 American Society of International Law, 1940-58 American Society for Public Administration, 1944-59 Autobiographical, Recollections, and Biographical, 1951, 1958, 1977-79, 1989 Box 3: Beard (Charles A.) reply, 1939-41 Blaisdell, D. C., 1948-56 Book Reviews, 1942-58 Brookings Institution, 1947-55 Chicago broadcast, 1952 College policy Commission to study the organization of peace, 1939-58 Committee on admissions from higher institutions, 1941-44 Committee of the Conference of Teachers of International Law, 1928-41 Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, 1940-42 Committee on School of Journalism, 1938-47 Box 4: Conference of Teachers of International Law, 1946, 1952 Correspondence, general, 1925-58 Council on Foreign Relations, 1946-57 Cosmos Club, 1942-58 Department of Political Science, 1933-39 Box 5: Department of Political Science, 1935-50 DeVoto, Bernard, 1955 Dial Club, 1929-58 Dictionary of American History, 1937-39 Dilliard, Irving, 1941-58 Document and Readings in American Government, 1938-54 Douglas, Sen. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

Morris Childs Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf896nb2v4 No online items Register of the Morris Childs papers Finding aid prepared by Lora Soroka and David Jacobs Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6010 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1999 Register of the Morris Childs 98069 1 papers Title: Morris Childs papers Date (inclusive): 1924-1995 Collection Number: 98069 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English and Russian Physical Description: 2 manuscript boxes, 35 microfilm reels(4.3 linear feet) Abstract: Correspondence, reports, notes, speeches and writings, and interview transcripts relating to Federal Bureau of Investigation surveillance of the Communist Party, and the relationship between the Communist Party of the United States and the Soviet communist party and government. Includes some papers of John Barron used as research material for his book Operation Solo: The FBI's Man in the Kremlin (Washington, D.C., 1996). Hard-copy material also available on microfilm (2 reels). Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Childs, Morris, 1902-1991. Contributor: Barron, John, 1930-2005. Location of Original Materials J. Edgar Hoover Foundation (in part). Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items, computer media, and digital files. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos, films, or digital files during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all material is immediately accessible. -

Liberalism, Radicalism, and Legal Scholarship Steven H

Cornell Law Library Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 8-1983 Liberalism, Radicalism, and Legal Scholarship Steven H. Shiffrin Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons, and the Legal History, Theory and Process Commons Recommended Citation Shiffrin, Steven H., "Liberalism, Radicalism, and Legal Scholarship" (1983). Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 1176. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/1176 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE LIBERALISM, RADICALISM, AND LEGAL SCHOLARSHIP Steven Shiffrin*t INTRODUCTION In the eighteenth century, Kant answered the utilitarians.I In the nineteenth century, without embracing utilitarianism, 2 Hegel * Professor of Law, UCLA. This project started out as a broad piece entitled "Away From a General Theory of the First Amendment." It has taken on un- bounded proportions and might as well be called "Away From A General Theory of Everything." During the several years I have worked on it, more than thirty friends and colleagues have read one version or another and have given me helpful com- ments. Listing them all would look silly, but I am grateful to each of them, especially to those who responded in such detail. I would especially like to thank Dru Cornell, who served early in the project as a research assistant and thereafter offered counsel, particularly lending her expertise on continental philosophy. -

A Socialist Schism

A Socialist Schism: British socialists' reaction to the downfall of Milošević by Andrew Michael William Cragg Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Marsha Siefert Second Reader: Professor Vladimir Petrović CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 Copyright notice Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract This work charts the contemporary history of the socialist press in Britain, investigating its coverage of world events in the aftermath of the fall of state socialism. In order to do this, two case studies are considered: firstly, the seventy-eight day NATO bombing campaign over the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999, and secondly, the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević in October of 2000. The British socialist press analysis is focused on the Morning Star, the only English-language socialist daily newspaper in the world, and the multiple publications affiliated to minor British socialist parties such as the Socialist Workers’ Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain (Provisional Central Committee). The thesis outlines a broad history of the British socialist movement and its media, before moving on to consider the case studies in detail. -

"The Crisis in the Communist Party," by James Casey

THE CRISIS in the..; COMMUNIST PARTY By James Casey Price IDc THREE ARROWS PRESS 21 East 17th Street New York City CHAPTER I THE PEOPlES FRONT AND MEl'tIBERSHIP The Communist Party has always prided itself on its «line." It has always boasted of being a "revolutionary work-class party with a Marxist Leninist line." Its members have been taught to believe that the party cannot be wrong at any time on any question. Nonetheless, today this Communist Party line has thrown the member ship of the Communist Party into a Niagara of Confusion. There are old members who insist that the line or program has not been changed. There are new members who assert just as emphatically that the line certainly has been changed and it is precisely because of this change that they have joined the party. Hence there is a clash of opinion which is steadily mov ing to the boiling point. Assuredly the newer members are correct in the first part of their contention that the basic program of the Communist Party has been changed. They are wrong when they hold that this change has been for the better. Today the Communist Party presents and seeks to carry out the "line" of a People's Front organization. And with its slogan of a People's Front, it has wiped out with one fell swoop, both in theory and in practice, the fundamental teachings of Karl Marx and Freidrick Engels. It, too, disowns in no lesser degree in deeds, if not yet in words, all the preachings and hopes of Nicolai Lenin, great interpretor of Marx and founder of the U. -

USA and RADICAL ORGANIZATIONS, 1953-1960 FBI Reports from the Eisenhower Library

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in American Radicalism General Editors: Mark Naison and Maurice Isserman THE COMMUNIST PARTY USA AND RADICAL ORGANIZATIONS, 1953-1960 FBI Reports from the Eisenhower Library UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in American Radicalism General Editors: Mark Naison and Maurice Isserman THE COMMUNIST PARTY, USA, AND RADICAL ORGANIZATIONS, 1953-1960 FBI Reports from the Eisenhower Library Project Coordinator and Guide Compiled by Robert E. Lester A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Communist Party, USA, and radical organizations, 1953-1960 [microform]: FBI reports from the Eisenhower Library / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels. - (Research collections in American radicalism) Accompanied by printed reel guide compiled by Robert E. Lester. ISBN 1-55655-195-9 (microfilm) 1. Communism-United States--History--Sources--Bibltography-- Microform catalogs. 2. Communist Party of the United States of America~History~Sources~Bibliography~Microform catalogs. 3. Radicalism-United States-History-Sources-Bibliography-- Microform catalogs. 4. United States-Politics and government-1953-1961 -Sources-Bibliography-Microform catalogs. 5. Microforms-Catalogs. I. Lester, Robert. II. Communist Party of the United States of America. III. United States. Federal Bureau of Investigation. IV. Series. [HX83] 324.27375~dc20 92-14064 CIP The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the White House Office, Office of the Special Assistant for National Security Affairs in the custody of the Eisenhower Library, National Archives and Records Administration. -

Radical Politics Between Protest and Parliament

tripleC 15(2): 459-476, 2017 http://www.triple-c.at The Alternative to Occupy? Radical politics between protest and parliament Emil Husted* and Allan Dreyer Hansen** *Department of Organization, Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, Denmark, www.cbs.dk/en/staff/ehioa **Department of Social Sciences and Business, Roskilde University, Roskilde, Den- mark, www.ruc.dk/~adh Abstract: In this paper, we compare the political anatomy of two distinct enactments of (left- ist) radical politics: Occupy Wall Street, a large social movement in the United States, and The Alternative, a recently elected political party in Denmark. Based on Ernesto Laclau’s conceptualization of ‘the universal’ and ‘the particular’, we show how the institutionalization of radical politics (as carried out by The Alternative) entails a move from universality towards particularity. This move, however, comes with the risk of cutting off supporters who no longer feel represented by the project. We refer to this problem as the problem of particularization. In conclusion, we use the analysis to propose a conceptual distinction between radical movements and radical parties: While the former is constituted by a potentially infinite chain of equivalent grievances, the latter is constituted by a prioritized set of differential demands. While both are important, we argue that they must remain distinct in order to preserve the universal spirit of contemporary radical politics. Keywords: Radical Politics, Radical Movements, Radical Parties, Discourse Theory, Ernesto Laclau, Universalism, Particularism, Occupy Wall Street, The Alternative Acknowledgement: First of all, we would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editorial team at tripleC for their constructive comments. -

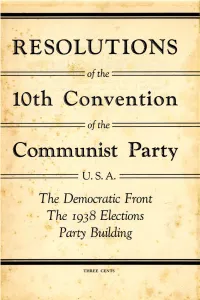

Resolutions of the 10Th Convention of the Communist Party, U.S.A

RESOLU.TIONS ============'==' ofthe ============== " , 10th C'onvention ==============.=. ofthe ============== Communist Party ====:::::::::===:::::::= tJ. S. A. ============= ": The Democra.tic Front ~ ~ T~e 1938 Elections Party Building THREE CENTS NOTE These Resolutions were unanimously adopted by the Tenth National Convention of the Communist Party, U.S.A., held in New York, May 27 to 31, 1938, after two months of pre-convention discussion by the'enti're: membership in every local branch and unit. They should be read in connection with the report to the Convention by Earl Browder, General Secretary, in behalf of the National Committee, published under the title The Democratic Front: For Jobs, Security, Democracy and Peace. (Workers Library Publishers. 96 pages; price 10 ,cents.) PUBLISHED BY WORKERS LIBRARY PUBLISHERS, INC. P. O. BOX 1-48, STATION D, NEW YORK CITY JULY,, 1938 PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. THE OFFENSIVE OF REACTION AND THE BUILDING OF THE DEMOCRATIC FRONT I A S PART of the world offensive of fascism, which is l""\..already extending to the Americas, the most reactionary section of finance capital in the United States is utilizing the developing economic crisis, which it has itself hastened and aggravated, as the basis for a major attack against the rising labor and democratic movements. This reactionary section of American finance capital con tinues on a "sit-down strike" to defeat Roosevelt's progressive measures and for the purpose of forcing America onto the path of reaction, the path toward fascism and war. It exploi~s the slogans of isolation to manipulate the peace sentiments of the masses, who are still unclear on how to maintain peace. -

Finding Aid Prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISION THE RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTION Finding aid prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C. - Library of Congress - 1995 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK ANtI SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISIONS RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTIONS The Radical Pamphlet Collection was acquired by the Library of Congress through purchase and exchange between 1977—81. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 25 Number of items: Approx: 3465 Scope and Contents Note The Radical Pamphlet Collection spans the years 1870-1980 but is especially rich in the 1930-49 period. The collection includes pamphlets, newspapers, periodicals, broadsides, posters, cartoons, sheet music, and prints relating primarily to American communism, socialism, and anarchism. The largest part deals with the operations of the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA), its members, and various “front” organizations. Pamphlets chronicle the early development of the Party; the factional disputes of the 1920s between the Fosterites and the Lovestoneites; the Stalinization of the Party; the Popular Front; the united front against fascism; and the government investigation of the Communist Party in the post-World War Two period. Many of the pamphlets relate to the unsuccessful presidential campaigns of CP leaders Earl Browder and William Z. Foster. Earl Browder, party leader be—tween 1929—46, ran for President in 1936, 1940 and 1944; William Z. Foster, party leader between 1923—29, ran for President in 1928 and 1932. Pamphlets written by Browder and Foster in the l930s exemplify the Party’s desire to recruit the unemployed during the Great Depression by emphasizing social welfare programs and an isolationist foreign policy. -

Overconfidence Chapter SSSP COMMENTS JF 11 August 2020

Running Head: OVERCONFIDENCE IN RADICAL POLITICS 1 Overconfidence in Radical Politics Jan-Willem van Prooijen1,2 1 VU Amsterdam 2 The Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement (NSCR) In J. P. Forgas, B. Crano, & K. Fiedler (Eds.), The Psychology of Populism. Oxon, UK: Routledge Correspondence to Jan-Willem van Prooijen, Department of Experimental and Applied Psychology, Van der Boechorststraat 7, 1081BT Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Email: [email protected] Running Head: OVERCONFIDENCE IN RADICAL POLITICS 2 Overconfidence in Radical Politics In the past decade, radical political movements have done well electorally. Populist movements have gained significant levels of public support in many EU countries including Italy, France, Hungary, Poland, Denmark, the Netherlands, and the UK. Also across many Latin American countries – including Brazil, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Nicaragua – political movements that are populist, nationalist, or extremist can rely on substantial levels of public support. This global momentum of radical political movements appears to be taking place at both the left and the right. For instance, not too long ago it would be considered unthinkable in the US that the radical right-wing (e.g., anti-immigrant) rhetoric of Donald Trump could get him elected President; but also, it would be considered unthinkable that a congress member who publicly proclaims to be a “Democratic Socialist” (i.e., Bernie Sanders) could be a serious contender for the Democratic party’s presidential nomination. The present chapter seeks to contribute to understanding the psychological appeal of relatively radical political movements among the public. Although many different radical political movements exist around the world, here I define radical political beliefs in terms of political extremism and/or populism.