Gendering the American Enemy in Early Cold War Soviet Films (1946–1953)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Academy Awards (Oscars), 34, 57, Antares , 2 1 8 98, 103, 167, 184 Antonioni, Michelangelo, 80–90, Actors ’ Studio, 5 7 92–93, 118, 159, 170, 188, 193, Adaptation, 1, 3, 23–24, 69–70, 243, 255 98–100, 111, 121, 125, 145, 169, Ariel , 158–160 171, 178–179, 182, 184, 197–199, Aristotle, 2 4 , 80 201–204, 206, 273 Armstrong, Gillian, 121, 124, 129 A denauer, Konrad, 1 3 4 , 137 Armstrong, Louis, 180 A lbee, Edward, 113 L ’ Atalante, 63 Alexandra, 176 Atget, Eugène, 64 Aliyev, Arif, 175 Auteurism , 6 7 , 118, 142, 145, 147, All About Anna , 2 18 149, 175, 187, 195, 269 All My Sons , 52 Avant-gardism, 82 Amidei, Sergio, 36 L ’ A vventura ( The Adventure), 80–90, Anatomy of Hell, 2 18 243, 255, 270, 272, 274 And Life Goes On . , 186, 238 Anderson, Lindsay, 58 Baba, Masuru, 145 Andersson,COPYRIGHTED Karl, 27 Bach, MATERIAL Johann Sebastian, 92 Anne Pedersdotter , 2 3 , 25 Bagheri, Abdolhossein, 195 Ansah, Kwaw, 157 Baise-moi, 2 18 Film Analysis: A Casebook, First Edition. Bert Cardullo. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 284 Index Bal Poussière , 157 Bodrov, Sergei Jr., 184 Balabanov, Aleksei, 176, 184 Bolshevism, 5 The Ballad of Narayama , 147, Boogie , 234 149–150 Braine, John, 69–70 Ballad of a Soldier , 174, 183–184 Bram Stoker ’ s Dracula , 1 Bancroft, Anne, 114 Brando, Marlon, 5 4 , 56–57, 59 Banks, Russell, 197–198, 201–204, Brandt, Willy, 137 206 BRD Trilogy (Fassbinder), see FRG Barbarosa, 129 Trilogy Barker, Philip, 207 Breaker Morant, 120, 129 Barrett, Ray, 128 Breathless , 60, 62, 67 Battle -

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

The Synthesis of Jazz and Classical Styles in Three Piano Works of Nikolai Kapustin

THE SYNTHESIS OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL STYLES IN THREE PIANO WORKS OF NIKOLAI KAPUSTIN __________________________________________________ A monograph Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board __________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS __________________________________________________________ by Tatiana Abramova August 2014 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Charles Abramovic, Advisory Chair, Professor of Piano Harvey Wedeen, Professor of Piano Dr. Cynthia Folio, Professor of Music Studies Richard Oatts, External Member, Professor, Artistic Director of Jazz Studies ABSTRACT The Synthesis of Jazz and Classical Styles in Three Piano Works of Nikolai Kapustin Tatiana Abramova Doctor of Musical Arts Temple University, 2014 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Charles Abramovic The music of the Russian-Ukrainian composer Nikolai Kapustin is a fascinating synthesis of jazz and classical idioms. Kapustin has explored many existing traditional classical forms in conjunction with jazz. Among his works are: 20 piano sonatas, Suite in the Old Style, Op.28, preludes, etudes, variations, and six piano concerti. The most significant work in this regard is a cycle of 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 82, which was completed in 1997. He has also written numerous works for different instrumental ensembles and for orchestra. Well-known artists, such as Steven Osborn and Marc-Andre Hamelin have made a great contribution by recording Kapustin's music with Hyperion, one of the major recording companies. Being a brilliant pianist himself, Nikolai Kapustin has also released numerous recordings of his own music. Nikolai Kapustin was born in 1937 in Ukraine. He started his musical career as a classical pianist. In 1961 he graduated from the Moscow Conservatory, studying with the legendary pedagogue, Professor of Moscow Conservatory Alexander Goldenweiser, one of the greatest founders of the Russian piano school. -

GÜRCÜ SİNEMASI Ve TENGİZ ABULADZE

T.C. DOKUZ EYLÜL ÜNİVERSİTESİ GÜZEL SANATLAR ENSTİTÜSÜ SİNEMA – TV ANASANAT DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ GÜRCÜ SİNEMASI ve TENGİZ ABULADZE Hazırlayan Duygu YILMAZ Danışman Yrd. Doç. Dr. Zühal ÇETİN ÖZKAN İZMİR–2008 Yüksek lisans tezi olarak sunduğum “Gürcü Sineması ve Tengiz Abuladze” adlı çalışmanın, tarafımdan, bilimsel ahlak ve geleneklere aykırı düşecek bir yardıma başvurmaksızın yazıldığını ve yararlandığım eserlerin bibliyografyada gösterilenlerden oluştuğunu, bunlara atıf yapılarak yararlanılmış olduğunu belirtir ve bunu onurumla doğrularım. Tarih ..../..../2008 DUYGU YILMAZ ii TUTANAK Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Enstitüsü’ nün ......./......../...... tarih ve ......sayılı toplantısında oluşturulan jüri, Lisansüstü Öğretim Yönetmeliği’nin ........maddesine göre ........................Anabilim Dalı ………..öğrencisi ..........................’ nin ...................konulu tezi/projesi incelenmiş ve aday ......./....../........ tarihinde, saat .......’ da jüri önünde tez savunmasına alınmıştır. Adayın kişisel çalışmaya dayanan tezini/projesini savunmasından sonra ......... dakikalık süre içinde gerek tez konusu, gerekse tezin dayanağı olan anabilim dallarından jüri üyelerine sorulan sorulara verdiği cevaplar değerlendirilerek tezin/projenin .............................olduğuna oy...................ile karar verildi. BAŞKAN ÜYE ÜYE (ÜYE) (ÜYE) iii YÜKSEKÖĞRETİM KURULU DOKÜMANTASYON MERKEZİ TEZ/PROJE VERİ FORMU Tez/Proje No: Konu Kodu: Üniv. Kodu: Tez/Proje Yazarının Soyadı: YILMAZ Adı: DUYGU Tezin/Projenin Türkçe Adı: GÜRCÜ -

Nosferatu. Revista De Cine (Donostia Kultura)

Nosferatu. Revista de cine (Donostia Kultura) Título: Índices Autor/es: Nosferatu Citar como: Nosferatu (1999). Índices. Donostia Kultura. Documento descargado de: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/41162 Copyright: Reserva de todos los derechos (NO CC) La digitalización de este artículo se enmarca dentro del proyecto "Estudio y análisis para el desarrollo de una red de conocimiento sobre estudios fílmicos a través de plataformas web 2.0", financiado por el Plan Nacional de I+D+i del Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad del Gobierno de España (código HAR2010-18648), con el apoyo de Biblioteca y Documentación Científica y del Área de Sistemas de Información y Comunicaciones (ASIC) del Vicerrectorado de las Tecnologías de la Información y de las Comunicaciones de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Entidades colaboradoras: • • lndice onomástico Adorée, Renée: 8, 80 Davies, Marion: 21, 22 Agee, James: 41 Davis, Bette: 32 Alessandrini, Goffredo: 50 Davis, Carl: 86 Andreiev: 94 De Laurentiis, Dino: 34, 79, 88 Arto, Florence: 15, 16, 17 DeMille, Cecil B.: 6, 15 Asquith, Anthony: 28 De Robertis: 8 De Santis, Giuseppe: 38 Baldelli, Pío: 13 De Sica, Vittorio: 8, 9 Barahona, Fernando: 45, 50 Del Río, Dolores: 25 Bardem, Juan Antonio: 45 Delahaye, Michael: 13, 36 Barrymore, Lionel: 26, 74 Delgado, Manuel: 53, 58 Barthes, Roland: 61 Dickinson, Emily: 41 Bazin, André: 9, 13 Dieterle, Wil!iam: 30, 73 Beauchamp, D.D.: 74 Donat, Robert: 28 , 65 Beery, Wallace: 11, 12, 25, 36,91 Donen, Stanley: 22 Berge, Catherine: 12 Donskoi, Mark: 38 Bergman, Andrew: -

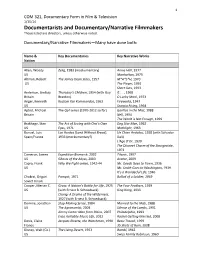

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

Speech at a Ceremony Marking the Centenary of the Communist Party of China July 1, 2021

Speech at a Ceremony Marking the Centenary of the Communist Party of China July 1, 2021 Xi Jinping Comrades and friends, Today, the first of July, is a great and solemn day in the history of both the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Chinese nation. We gather here to join all Party members and Chinese people of all ethnic groups around the country in celebrating the centenary of the Party, looking back on the glorious journey the Party has traveled over 100 years of struggle, and looking ahead to the bright prospects for the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. To begin, let me extend warm congratulations to all Party members on behalf of the CPC Central Committee. On this special occasion, it is my honor to declare on behalf of the Party and the people that through the continued efforts of the whole Party and the entire nation, we have realized the first centenary goal of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects. This means that we have brought about a historic resolution to the problem of absolute poverty in China, and we are now marching in confident strides toward the second centenary goal of building China into a great modern socialist country in all respects. This is a great and glorious accomplishment for the Chinese nation, for the Chinese people, and for the Communist Party of China! Comrades and friends, The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history of more than 5,000 years, China has made indelible contributions to the progress of human civilization. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Representations of the Holocaust in Soviet cinema Timoshkina, Alisa Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 REPRESENTATIONS OF THE HOLOCAUST IN SOVIET CINEMA Alissa Timoshkina PhD in Film Studies 1 ABSTRACT The aim of my doctoral project is to study how the Holocaust has been represented in Soviet cinema from the 1930s to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. -

Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy

Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy How do democracies form and what makes them die? Daniel Ziblatt revisits this timely and classic question in a wide-ranging historical narrative that traces the evolution of modern political democracy in Europe from its modest beginnings in 1830s Britain to Adolf Hitler’s 1933 seizure of power in Weimar Germany. Based on rich historical and quantitative evidence, the book offers a major reinterpretation of European history and the question of how stable political democracy is achieved. The barriers to inclusive political rule, Ziblatt finds, were not inevitably overcome by unstoppable tides of socioeconomic change, a simple triumph of a growing middle class, or even by working class collective action. Instead, political democracy’s fate surprisingly hinged on how conservative political parties – the historical defenders of power, wealth, and privilege – recast themselves and coped with the rise of their own radical right. With striking modern parallels, the book has vital implications for today’s new and old democracies under siege. Daniel Ziblatt is Professor of Government at Harvard University where he is also a resident fellow of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies. He is also currently Fernand Braudel Senior Fellow at the European University Institute. His first book, Structuring the State: The Formation of Italy and Germany and the Puzzle of Federalism (2006) received several prizes from the American Political Science Association. He has written extensively on the emergence of democracy in European political history, publishing in journals such as American Political Science Review, Journal of Economic History, and World Politics. -

Programme Notes

Red Front May 9 - May 30 2020 Trial on the Road (1971) by Aleksei German World War 2, or as it is known to Russians, The Great Patriotic proved too challenging for the authorities. The film was War is one of the few conflicts where we can attribute clear shelved for 15 years. moral judgement. Most international conflict carries ambivalence, it is hard to unpick which side, or indeed sides, The ambiguity that starts with Lazarev certainly does not end are ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. The general consensus on WWII has led to with him. When imprisoned by the partisans, his cellmate is an a conception of heroes and villains, which has penetrated 18 year old boy and a fellow defector. Lazarev’s commanding national and historical consciousness across Europe for the and stoic screen presence is the perfect counterbalance to the better part of a century. The Soviet death toll stands, according boy’s desperation. As the young man cries of his desolation to a 1993 study by the Russian Academy of the Sciences, at and regret, Lazarev says nothing, although he definitely 26.6million. The intense strength of pride and remembrance understands. It is a heartbreaking scene, one which shows the that still resonates through the region today is equivocal to way trauma envelopes individuals, and leaves them unable to the magnitude of the tragedy. However, whilst most of us can extend comfort to themselves, let alone to others. There are confidently say that Nazism and fascism were terrible forces, many scenes of this nature in German’s film, characters and that the war was largely just, this says nothing of the breakdown and their sorrow is met with silence.