The Celtic Evil Eye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

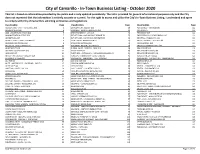

In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This List Is Based on Informa�On Provided by the Public and Is Only Updated Periodically

City of Camarillo - In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This list is based on informaon provided by the public and is only updated periodically. The list is provided for general informaonal purposes only and the City does not represent that the informaon is enrely accurate or current. For the right to access and ulize the City's In-Town Business Lisng, I understand and agree to comply with City of Camarillo's soliciting ordinances and regulations. Classification Page Classification Page Classification Page ACCOUNTING - CPA - TAX SERVICE (93) 2 EMPLOYMENT AGENCY (10) 69 PET SERVICE - TRAINER (39) 112 ACUPUNCTURE (13) 4 ENGINEER - ENGINEERING SVCS (34) 70 PET STORE (7) 113 ADD- LOCATION/BUSINESS (64) 5 ENTERTAINMENT - LIVE (17) 71 PHARMACY (13) 114 ADMINISTRATION OFFICE (53) 7 ESTHETICIAN - HAS MASSAGE PERMIT (2) 72 PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEOGRAPHY (10) 114 ADVERTISING (14) 8 ESTHETICIAN - NO MASSAGE PERMIT (35) 72 PRINTING - PUBLISHING (25) 114 AGRICULTURE - FARM - GROWER (5) 9 FILM - MOVIE PRODUCTION (2) 73 PRIVATE PATROL - SECURITY (4) 115 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE (16) 9 FINANCIAL SERVICES (44) 73 PROFESSIONAL (33) 115 ANTIQUES - COLLECTIBLES (18) 10 FIREARMS - REPAIR / NO SALES (2) 74 PROPERTY MANAGEMENT (39) 117 APARTMENTS (36) 10 FLORAL-SALES - DESIGNS - GRW (10) 74 REAL ESTATE (18) 118 APPAREL - ACCESSORIES (94) 12 FOOD STORE (43) 75 REAL ESTATE AGENT (180) 118 APPRAISER (7) 14 FORTUNES - ASTROLOGY - HYPNOSIS(NON-MED) (3) 76 REAL ESTATE BROKER (31) 124 ARTIST - ART DEALER - GALLERY (32) 15 FUNERAL - CREMATORY - CEMETERIES (2) 76 REAL ESTATE -

Company Profile

www.ecobulpack.com COMPANY PROFILE KEEP BULGARIA CLEAN FOR THE CHILDREN! PHILIPPE ROMBAUT Chairman of the Board of Directors of ECOBULPACK Executive Director of AGROPOLYCHIM JSC-Devnia e, ECOBULPACK are dedicated to keeping clean the environment of the country we live Wand raise our children in. This is why we rely on good partnerships with the State and Municipal Authorities, as well as the responsible business managers who have supported our efforts from the very beginning of our activity. Because all together we believe in the cause: “Keep Bulgaria clean for the children!” VIDIO VIDEV Executive Director of ECOBULPACK Executive Director of NIVA JSC-Kostinbrod,VIDONA JSC-Yambol t ECOBULPACK we guarantee the balance of interests between the companies releasing A packed goods on the market, on one hand, and the companies collecting and recycling waste, on the other. Thus we manage waste throughout its course - from generation to recycling. The funds ECOBULPACK accumulates are invested in the establishment of sustainable municipal separate waste collection systems following established European models with proven efficiency. DIMITAR ZOROV Executive Director of ECOBULPACK Owner of “PARSHEVITSA” Dairy Products ince the establishment of the company we have relied on the principles of democracy as Swell as on an open and fair strategy. We welcome new shareholders. We offer the business an alternative in fulfilling its obligations to utilize packaged waste, while meeting national legislative requirements. We achieve shared responsibilities and reduce companies’ product- packaging fees. MILEN DIMITROV Procurator of ECOBULPACK s a result of our joint efforts and the professionalism of our work, we managed to turn AECOBULPACK JSC into the largest organization utilizing packaging waste, which so far have gained the confidence of more than 3 500 companies operating in the country. -

Evil Eye Belief in Turkish Culture: Myth of Evil Eye Bead

The Turkish Online Journal of Design, Art and Communication - TOJDAC April 2016 Volume 6 Issue 2 EVIL EYE BELIEF IN TURKISH CULTURE: MYTH OF EVIL EYE BEAD Bilgen TUNCER MANZAKOĞLU [email protected] Saliha TÜRKMENOĞLU BERKAN Doğuş University, Industrial Product Design Department [email protected] ABSTRACT Evil eye belief is found in many parts of the world and it plays a major social role in a large number of cultural contexts. The history of evil eye bead usage dated back to ancient times, but upon time it’s meaning have been re-constructed by culture. This paper focused on an amulet based commodity “evil eye bead” used against evil eye and for ornament in Turkey. In order to analyze the myth of evil eye bead, two-sectioned survey was conducted. First section determined evil eye belief rate, participant profile and objects against evil eye. In the second section, the semantic dimensions of evil eye bead was analyzed in the myth level encompassing its perception and function as a cultural opponent act. This paper interrogated the role of culture, geography, and history on the evil eye bead myth. Keywords: Evil Eye Bead, Culture, Myth, Semiology. TÜRK KÜLTÜRÜNDE NAZAR İNANCI: NAZAR BONCUĞU MİTİ ÖZ Nazar inancı dünyanın bir çok bölgesinde bulunmakta ve kültürel bağlamda önemli bir sosyal rol üstlenmektedir.Nazar boncuğunun kullanımı antik zamanlara dayanmakla birlikte, taşıdığı anlam zaman içerisinde kültür ile birlikte yeniden inşa edilmiştir. Türkiye’de hem süs eşyası hem de kem göze karşı kullanılan nazar boncuğu bu makalenin ana konusudur. Nazar boncuğu mitini analiz etmek için iki aşamalı anket çalışması yürütülmüştür. -

Do Public Fund Windfalls Increase Corruption? Evidence from a Natural Disaster Elena Nikolovaa Nikolay Marinovb 68131 Mannheim A5-6, Germany October 5, 2016

Do Public Fund Windfalls Increase Corruption? Evidence from a Natural Disaster Elena Nikolovaa Nikolay Marinovb 68131 Mannheim A5-6, Germany October 5, 2016 Abstract We show that unexpected financial windfalls increase corruption in local govern- ment. Our analysis uses a new data set on flood-related transfers, and the associated spending infringements, which the Bulgarian central government distributed to mu- nicipalities following torrential rains in 2004 and 2005. Using information from the publicly available audit reports we are able to build a unique objective index of cor- ruption. We exploit the quasi-random nature of the rainfall shock (conditional on controls for ground flood risk) to isolate exogenous variation in the amount of funds received by each municipality. Our results imply that a 10 % increase in the per capita amount of disbursed funds leads to a 9.8% increase in corruption. We also present suggestive evidence that more corrupt mayors anticipated punishment by voters and dropped out of the next election race. Our results highlight the governance pitfalls of non-tax transfers, such as disaster relief or assistance from international organizations, even in moderately strong democracies. Keywords: corruption, natural disasters, governance JEL codes: D73, H71, P26 aResearch Fellow, Central European Labour Studies Institute, Slovakia and associated researcher, IOS Regensburg, Germany. Email: [email protected]. We would like to thank Erik Bergl¨of,Rikhil Bhav- nani, Simeon Djankov, Sergei Guriev, Stephan Litschig, Ivan Penkov, Grigore Pop-Eleches, Sandra Sequeira and conference participants at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the European Public Choice Society, Groningen, the 2015 American Political Science Association, San Francisco and seminar participants at Brunel, King's College workshop on corruption, and LSE for useful comments, and Erik Bergl¨ofand Stefka Slavova for help with obtaining Bulgarian rainfall data. -

Annex REPORT for 2019 UNDER the “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY of the REPUBLIC of BULGAR

Annex REPORT FOR 2019 UNDER THE “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2012 - 2020 Operational objective: A national monitoring progress report has been prepared for implementation of Measure 1.1.2. “Performing obstetric and gynaecological examinations with mobile offices in settlements with compact Roma population”. During the period 01.07—20.11.2019, a total of 2,261 prophylactic medical examinations were carried out with the four mobile gynaecological offices to uninsured persons of Roma origin and to persons with difficult access to medical facilities, as 951 women were diagnosed with diseases. The implementation of the activity for each Regional Health Inspectorate is in accordance with an order of the Minister of Health to carry out not less than 500 examinations with each mobile gynaecological office. Financial resources of BGN 12,500 were allocated for each mobile unit, totalling BGN 50,000 for the four units. During the reporting period, the mobile gynecological offices were divided into four areas: Varna (the city of Varna, the village of Kamenar, the town of Ignatievo, the village of Staro Oryahovo, the village of Sindel, the village of Dubravino, the town of Provadia, the town of Devnya, the town of Suvorovo, the village of Chernevo, the town of Valchi Dol); Silistra (Tutrakan Municipality– the town of Tutrakan, the village of Tsar Samuel, the village of Nova Cherna, the village of Staro Selo, the village of Belitsa, the village of Preslavtsi, the village of Tarnovtsi, -

1 I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and List of Rural Municipalities in Bulgaria

I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and list of rural municipalities in Bulgaria (according to statistical definition). 1 List of rural municipalities in Bulgaria District District District District District District /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality Blagoevgrad Vidin Lovech Plovdiv Smolyan Targovishte Bansko Belogradchik Apriltsi Brezovo Banite Antonovo Belitsa Boynitsa Letnitsa Kaloyanovo Borino Omurtag Gotse Delchev Bregovo Lukovit Karlovo Devin Opaka Garmen Gramada Teteven Krichim Dospat Popovo Kresna Dimovo Troyan Kuklen Zlatograd Haskovo Petrich Kula Ugarchin Laki Madan Ivaylovgrad Razlog Makresh Yablanitsa Maritsa Nedelino Lyubimets Sandanski Novo Selo Montana Perushtitsa Rudozem Madzharovo Satovcha Ruzhintsi Berkovitsa Parvomay Chepelare Mineralni bani Simitli Chuprene Boychinovtsi Rakovski Sofia - district Svilengrad Strumyani Vratsa Brusartsi Rodopi Anton Simeonovgrad Hadzhidimovo Borovan Varshets Sadovo Bozhurishte Stambolovo Yakoruda Byala Slatina Valchedram Sopot Botevgrad Topolovgrad Burgas Knezha Georgi Damyanovo Stamboliyski Godech Harmanli Aitos Kozloduy Lom Saedinenie Gorna Malina Shumen Kameno Krivodol Medkovets Hisarya Dolna banya Veliki Preslav Karnobat Mezdra Chiprovtsi Razgrad Dragoman Venets Malko Tarnovo Mizia Yakimovo Zavet Elin Pelin Varbitsa Nesebar Oryahovo Pazardzhik Isperih Etropole Kaolinovo Pomorie Roman Batak Kubrat Zlatitsa Kaspichan Primorsko Hayredin Belovo Loznitsa Ihtiman Nikola Kozlevo Ruen Gabrovo Bratsigovo Samuil Koprivshtitsa Novi Pazar Sozopol Dryanovo -

9.2 Housing Market

Public Disclosure Authorized BULGARIA Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Housing Sector Assessment F i n a l R e p o r t Prepared for Ministry of Regional Development and Public Works Public Disclosure Authorized By The World Bank June2017 HOUSING IN BULGARIA Organization of the Document To facilitate ease of reading – given the length and complexity of the full report – this document includes the following: - A 5-page Executive Summary, which highlights the key messages; - A 20-page Short Report, which presents in some level of detail the analysis, together with the main conclusions and recommendations; - A 150-page Main Report, which includes the full Situation Analysis, followed by Findings and Recommendations in detail. i HOUSING IN BULGARIA Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations IV Currency Equivalents VI Acknowledgements VII Executive Summary 1 Short Report 6 Main Report 27 SITUATION ANALYSIS 29 INTRODUCTION 31 1.1 Context 31 1.2 Relevance to the CPF and other World Bank projects 33 HOUSING AND URBANIZATION 35 2.1 Population Trends 35 2.2 Emigration 35 2.3 City typologies and trends 38 HOUSING STOCK AND QUALITY 41 3.1 Housing Stock 41 3.2 Ownership and Tenure 46 3.3 Housing Quality 50 PROGRAMS, INSTITUTIONS, LAWS, AND PROCEDURES 56 4.1 Current Approach to Housing 56 4.2 EU- and State-Funded Programs in the Housing Sector 56 4.3 Other State support for housing 61 4.4 Public Sector Stakeholders 69 4.5 Legal Framework 71 i HOUSING IN BULGARIA 4.6 Relevant Legislation and Processes for Housing 80 LOWER INCOME AND -

Transport and Logistics in Bulgaria

Investing in your future EUROPEAN UNION OP “Development of the Competitiveness of the Bulgarian European Regional Economy” 2007-2013 Development Fund Project “Promoting the advantages of investing in Bulgaria” BG 161PO003-4.1.01-0001-C0001, with benefi ciary InvestBulgaria Agency, has been implemented with the fi nancial support of the European Union through the European Fund for Regional Development and the national budget of the Republic of Bulgaria. TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS IN BULGARIA CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 2. Overview of Bulgaria 10 3. Overview of the Transport& Logistics sector 14 4. Human Resources 45 5. Success Stories 53 Introduction Bulgaria is ideally located to provide easy access to Turkey, and the Middle East 4 Introductiont the markets in Europe, Russia, the CIS countires, BULGARIA is a member of the EUROPEAN UNION which stands for FREE MOVEMENT OF GOODS FIVE PAN-EUROPEAN CORRIDORS pass through the country TRACECA (TRAnsport Corridor Europe – Caucasus – Asia) links Bulgaria with Central Asia Source: InvestBulgaria Agency 5 Introduction Bulgaria offers easy access to the EU, Russia and the CIS countries, and the Middle East at the same time City Sofi a Belgrade Budapest Distance Days by Distance Days by Distance Days by (km) truck (km) truck (km) truck European Union Munich 1 097 3 773 2 564 1 Antwerp 1 711 4 1 384 3 1 137 2 Milan 1 167 3 885 2 789 1 Piraeus 525 1 806 2 1 123 3 Russia and CIS Moscow 1 777 5 1 711 5 1 565 5 Kiev 1 021 4 976 3 894 3 Middle East Istanbul 503 1 809 2 1 065 3 Kuwait City 2 623 12 2 932 13 3 -

Bulgaria Service Centers / Updated 11/03/2015

Bulgaria Service Centers / Updated 11/03/2015 Country Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D DASP name Progress Progress Progress Progress Center Center Center Center Sofia 1574 69a Varna 9000 Varna 9000 Burgas 8000 Shipchenski Slivntisa Blvd Kaymakchala Konstantin Address (incl. post code) and Company Name prohod blvd. 147 bl 19A n Str. 10A. Velichkov 34, CAD R&D appt. Flysystem 1 fl. Kontrax Progress Vizicomp Center Country Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria City Sofia Varna Varna Burgas General phone number 02 870 4159 052 600 380 052 307 105 056 813 516 Business Business Business Business Opening days/hours hours: 9:00– hours: 9:00– hours: 9:00– hours: 9:00– 17:30 17:30 17:30 17:30 Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Center Center Center Center Center Center Center Center Center Ruse 7000 Shumen Stara Zagora Plovdiv 4000 Burgas 8000 Pleven 5800 Sliven 8800 Pernik 2300 Burgas 8000 Tsarkovna 9700 Simeon 6000 Ruski Bogomil Blvd Demokratsiy San Stefano Dame Gruev Krakra Str Samouil 12A. Nezavisimost Veliki Str 5. Blvd 51. 91. Pic a Blvd 67. Str 30. Str 30. Best 68. Krakra Infostar Str 27. SAT Com Viking Computer Pic Burgas Infonet Fix Soft Dartek Group Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Burgas Stara Zagora Plovdiv Burgas Pleven Ruse Sliven Pernik Shumen 056 803 065 042 -

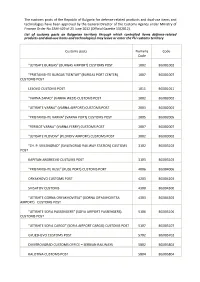

The Customs Posts of the Republic of Bulgaria for Defence-Related

The customs posts of the Republic of Bulgaria for defence-related products and dual-use items and technologies have been approved by the General Director of the Customs Agency under Ministry of Finance Order No ZAM-429 of 25 June 2012 (Official Gazette 53/2012). List of customs posts on Bulgarian territory through which controlled items defence-related products and dual-use items and technologies) may leave or enter the EU customs territory Customs posts Numeric Code Code “LETISHTE BURGAS” (BURGAS AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST 1002 BG001002 “PRISTANISHTE BURGAS TSENTAR” (BURGAS PORT CENTER) 1007 BG001007 CUSTOMS POST LESOVO CUSTOMS POST 1011 BG001011 “VARNA ZAPAD” (VARNA WEST) CUSTOMS POST 2002 BG002002 “LETISHTE VARNA” (VARNA AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST 2003 BG002003 “PRISTANISHTE VARNA” (VARNA PORT) CUSTOMS POST 2005 BG002005 “FERIBOT VARNA” (VARNA FERRY) CUSTOMS POST 2007 BG002007 “LETISHTE PLOVDIV” (PLOVDIV AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST 3002 BG003002 “ZH. P. SVILENGRAD” (SVILENGRAD RAILWAY STATION) CUSTOMS 3102 BG003102 POST KAPITAN ANDREEVO CUSTUMS POST 3103 BG003103 “PRISTANISHTE RUSE” (RUSE PORT) CUSTOMS PORT 4006 BG004006 ORYAKHOVO CUSTOMS POST 4203 BG004203 SVISHTOV CUSTOMS 4300 BG004300 “LETISHTE GORNA ORYAKHOVITSA” (GORNA ORYAKHOVITSA 4303 BG004303 AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST “LETISHTE SOFIA PASSENGERS” (SOFIA AIRPORT PASSENGERS) 5106 BG005106 CUSTOMS POST “LETISHTE SOFIA CARGO” (SOFIA AIRPORT CARGO) CUSTOMS POST 5107 BG005107 GYUESHEVO CUSTOMS POST 5702 BG005702 DIMITROVGRAD CUSTOMS OFFICE – SERBIAN RAILWAYS 5802 BG005802 KALOTINA CUSTOMS POST 5804 BG005804 -

Mountain Biking Tour

PIRT Mountain Biking Tour PROMOTING INNOVATIVE RURAL TOURISM IN THE BLACK SEA BASIN REGION 2014 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Itinerary 2. Bulgaria-Turkey ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Additional Sites Included in the Itinerary Nr. 2 ............................................................................................................................................................ 17 Introduction For a ticket to adventure, bring your mountain bike to the Black Sea Region. The four countries around the Black Sea- Bulgaria, Turkey, Georgia and Armenia, are a paradise for mountain biking with innumerable cycle routes on gravel roads, in the mountains and along rough cart roads. Their dramatic natural landscapes offer challenging and rewarding slick rock trails, lush green single track, ruins of ancient civilizations, canyons and secret paths to explore. The mountain biking in and around Black Sea is some of the best trail riding in Europe. There are no restrictions on using bikes on the routes. Most of the routes are suitable for energetic mountain biking. Mountain biking is best between May and June or September and October. Itinerary 2- The “Black Sea Discovery” -

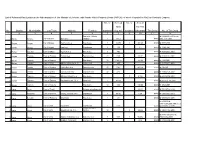

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry Of

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry of Defence, with Private Public Property Deeds (PPPDs), of which Property the MoD is Allowed to Dispose No. of Built-up No. of Area of Area the Plot No. District Municipality City/Town Address Function Buildings (sq. m.) Facilities (decares) Title Deed No. of Title Deed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Part of the Military № 874/02.05.1997 for the 1 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Slaveykov Hospital 1 545,4 PPPD whole real estate 2 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Kapcheto Area Storehouse 6 623,73 3 29,143 PPPD № 3577/2005 3 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Sarafovo Storehouse 6 439 5,4 PPPD № 2796/2002 4 Burgas Nesebar Town of Obzor Top-Ach Area Storehouse 5 496 PPPD № 4684/26.02.2009 5 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Honyat Area Barracks area 24 9397 49,97 PPPD № 4636/12.12.2008 6 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Storehouse 18 1146,75 74,162 PPPD № 1892/2001 7 Burgas Sozopol Town of Atiya Military station, by Bl. 11 Military club 1 240 PPPD № 3778/22.11.2005 8 Burgas Sredets Town of Sredets Velikin Bair Area Barracks area 17 7912 40,124 PPPD № 3761/05 9 Burgas Sredets Town of Debelt Domuz Dere Area Barracks area 32 5785 PPPD № 4490/24.04.2008 10 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Ahtopol Mitrinkovi Kashli Area Storehouse 1 0,184 PPPD № 4469/09.04.2008 11 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Tsarevo Han Asparuh Str., Bl.