Progress Indicator 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoomtext Quick Reference Guide Version 10

ZoomText Quick Reference Guide version 10 Contents Welcome to ZoomText 10 ................ 3 Cursor Enhancements ............................24 System Requirements ............................... 4 Focus Enhancements ..............................25 Installing ZoomText ................................. 5 Font Enhancements .................................26 Activating ZoomText ............................... 6 Desktop Finder ........................................27 Starting ZoomText .................................... 8 Web Finder ...............................................28 ZoomText User Interface ......................... 9 Text Finder ...............................................31 Enabling and Disabling ZoomText ...... 11 Smooth Panning ......................................33 Magnifier Toolbar .......................... 12 Reader Toolbar .............................. 35 Setting the Magnification level ............. 13 Turning Speech On and Off ...................36 Selecting a Zoom Window .................... 14 Adjusting the Speech Rate .....................37 Adjusting a Zoom Window ................... 16 Synthesizer Settings ................................38 Using the Freeze Window ..................... 17 Typing Echo .............................................39 Using View Mode ................................... 18 Mouse Echo ..............................................40 Dual Monitor Support ............................ 19 Verbosity...................................................41 Color Enhancements ............................. -

UI Design and Interaction Guide for Windows Phone 7

UI Design and Interaction Guide 7 for Windows Phone 7 July 2010 Version 2.0 UI Design and Interaction Guide for Windows Phone 7 July 2010 Version 2.0 This is pre-release documentation and is subject to change in future releases. This document supports a preliminary release of a software product that may be changed substantially prior to final commercial release. This docu- ment is provided for informational purposes only and Microsoft makes no warranties, either express or implied, in this document. Information in this document, including URL and other Internet Web site references, is subject to change without notice. The entire risk of the use or the results from the use of this document remains with the user. Unless otherwise noted, the companies, organizations, products, domain names, e-mail addresses, logos, people, places, and events depicted in examples herein are fictitious. No association with any real company, organization, product, domain name, e-mail address, logo, person, place, or event is intended or should be inferred. Complying with all applicable copyright laws is the responsibility of the user. Without limiting the rights under copyright, no part of this document may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), or for any purpose, without the express written permission of Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft may have patents, patent applications, trademarks, copyrights, or other intellectual property rights covering subject matter in this docu- ment. Except as expressly provided in any written license agreement from Microsoft, the furnishing of this document does not give you any license to these patents, trademarks, copyrights, or other intellectual property. -

Programming Pattern PF

PHP PROGRAMMING PATTERN FOR THE PROGRESS FEEDBACK USABILITY MECHANISM Drafted by Francy Diomar Rodríguez, Software and Systems PhD Student, Facultad de Informática. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. ([email protected]) Content 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 2 Progress Feedback UM design pattern ............................................................................. 1 3 Progress Feedback UM Pattern (PHP) ............................................................................. 3 1 Introduction This document presents an implementation-oriented design pattern and the respective programming pattern developed in PHP for the Progress Feedback usability mechanism (UM). 2 Progress Feedback UM design pattern This is a design pattern for implementing the Progress Feedback usability mechanism. The Solution section details the responsibilities that the usability functionality has to fulfil. The Structure section contains the proposed design and the Implementation section describes the steps necessary for codifying the proposed design. NAME Progress Feedback UM PROBLEM When a system process is likely to block the UI for longer than two seconds, the user must be informed about the progress of the requested task. CONTEXT Highly interactive web applications and time-consuming processes that interrupt the UI for longer than two seconds SOLUTION Components are required to fulfil the responsibilities associated with the UM. They are: A component that display the right progress indicator depending on the available information: time, percentage, number of units processed, task completed, if no quantities are known: Indeterminate Progress Indicator. Generate a server-side mechanism for the active process to update and report progress Create a cyclical process that queries the progress of a task until completion. A component to inform the user of task completion. A component that display the completion message and close the progress indicator. -

Progressbar for ASP.NET AJAX Copyright 1987-2010 Componentone LLC

ComponentOne ProgressBar for ASP.NET AJAX Copyright 1987-2010 ComponentOne LLC. All rights reserved. Corporate Headquarters ComponentOne LLC 201 South Highland Avenue 3rd Floor Pittsburgh, PA 15206 ∙ USA Internet: [email protected] Web site: http://www.componentone.com Sales E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 1.800.858.2739 or 1.412.681.4343 (Pittsburgh, PA USA Office) Trademarks The ComponentOne product name is a trademark and ComponentOne is a registered trademark of ComponentOne LLC. All other trademarks used herein are the properties of their respective owners. Warranty ComponentOne warrants that the original CD (or diskettes) are free from defects in material and workmanship, assuming normal use, for a period of 90 days from the date of purchase. If a defect occurs during this time, you may return the defective CD (or disk) to ComponentOne, along with a dated proof of purchase, and ComponentOne will replace it at no charge. After 90 days, you can obtain a replacement for a defective CD (or disk) by sending it and a check for $25 (to cover postage and handling) to ComponentOne. Except for the express warranty of the original CD (or disks) set forth here, ComponentOne makes no other warranties, express or implied. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information contained in this manual is correct as of the time it was written. We are not responsible for any errors or omissions. ComponentOne’s liability is limited to the amount you paid for the product. ComponentOne is not liable for any special, consequential, or other damages for any reason. -

Interactive and Explorable 360 VR System with Visual Guidance User Interfaces

RealNodes: Interactive and Explorable 360◦ VR System with Visual Guidance User Interfaces ABSTRACT Emerging research expands the idea of using 360-degree panora- mas of the real-world for “360 VR” experiences beyond video and image viewing. However, most of these are strictly guided, with few opportunities for interaction or exploration. There is a desire for experiences with cohesive virtual environments with choice in navigation, versus scripted experiences with limited interaction. Un- like standard VR with the freedom of synthetic graphics, there are challenges in designing user interfaces (UIs) for 360 VR navigation within the limitations of fixed assets. We designed RealNodes, a novel software system that presents an interactive and explorable 360 VR environment. We also developed four visual guidance UIs for 360 VR navigation. The results of a comparative study of these UIs determined that choice of user interface (UI) had a significant effect on task completion times, showing one of the methods, Ar- row, was best. Arrow also exhibited positive but non-significant trends in preference, user engagement, and simulator-sickness. Re- alNodes and the comparative study contribute preliminary results that inspire future investigation of how to design effective visual guidance metaphors for navigation in applications using novel 360 VR environments. Keywords: Immersive / 360° video; 3D user interaction; Non- fatiguing 3DUIs; Locomotion and navigation; 3DUI metaphors; Computer graphics techniques Index Terms: Human-centered computing—Human computer Figure 1: Images from the RealNodes software displaying the four interaction (HCI)—Interaction paradigms—Virtual Reality; Human- types of visual guidance UI. (Top-left) Target; (Top-right) Arrow; centered computing—Interaction design —Interaction design pro- (Bottom-left) Path; (Bottom-right) Ripple. -

The Data Surface Interaction Paradigm

EG UK Theory and Practice of Computer Graphics (2005) L. Lever, M. McDerby (Editors) The Data Surface Interaction Paradigm Rikard Lindell and Thomas Larsson Department of Computer Science Mälardalen University Sweden Abstract This paper presents, in contrasts to the desktop metaphor, a content centric data surface interaction paradigm for graphical user interfaces applied to music creativity improvisation. Issues taken into account were navigation and retrieval of information, collaboration, and creative open-ended tasks. In this system there are no windows, icons, menus, files or applications. Content is presented on an infinitely large two-dimensional surface navigated by incremental search, zoom, and pan. Commands are typed aided by contextual help, visual feedback, and text completion. Components provide services related to different content modalities. Synchronisation of data surface content sustains mutual awareness of actions and mutual modifiability. The prototype music tool was evaluated with 10 users; it supported services expected by users, their creativity in action, and awareness in collaboration. User responses to the prototype tool were: It feels free, it feels good for creativity, and it’s easy and fun to use. Categories and Subject Descriptors (according to ACM CCS): H.5.2 [Information interfaces and presentation]: User Interfaces 1. Introduction a component framework for creating compound documents that removed the need of monolithic applications on desktop The graphical user interface of today’s computers has its platforms [CDE95]. origin in the findings and inventions of Alan Kay at Xe- rox PARC in the 70s. With it came a lot of interaction ele- With the DSIP users do not have to conduct any explicit ments, techniques, and metaphors to explain and convey the file management. -

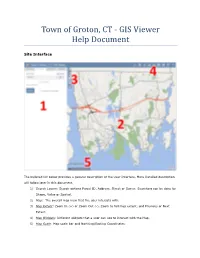

GIS Viewer Help Document

Town of Groton, CT - GIS Viewer Help Document Site Interface The bulleted list below provides a general description of the User Interface. More Detailed description will follow later in this document. 1) Search Layers: Search options Parcel ID, Address, Street or Owner. Searching can be done by Shape, Value or Spatial. 2) Map: The overall map view that the user interacts with. 3) Map Extent: Zoom In (+) or Zoom Out (-), Zoom to full map extent, and Previous or Next Extent. 4) Map Widgets: Different widgets that a user can use to interact with the Map. 5) Map Scale: Map scale bar and Northing/Easting Coordinates. Mouse and Keyboard Navigation • Click and drag to pan • SHIFT + Click to recenter • SHIFT + Drag to zoom in • SHIFT + CTRL + Drag to zoom out • Mouse Scroll Forward to zoom in • Mouse Scroll Backward to zoom out • Use Arrow keys to pan • + key to zoom in a level • - key to zoom out a level • Double Click to Center and Zoom in Touch Screen Navigation: (Only for Smartphones and Tablets) • Touch and drag to pan • Double tap or unpinch to zoom in • Pinch to zoom out. Click on the Town of Groton Seal (upper left corner) will bring you to the town’s website. Search Layers This widget can be searched By Shape or By Value. By Value The By Value view has a dropdown list of predefined search layers. Selecting a search layer updates the dropdown list of search aliases for that layer. In the search bar type in the Parcel ID, Address, Street or Owner that you're looking for. -

Mckesson Radiology™ Radiologist Manual

McKesson Radiology™ Radiologist Manual Revision 1.0 Document ID: 2016-35625 McKesson Radiology Radiologist Manual Table of Contents Chapter 1 – McKesson Terminology ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Chapter 2 – The McKesson Radiology PACS Dataflow ................................................................................................................. 7 Chapter 3 – Understanding McKesson Radiology ........................................................................................................................ 8 Logging on to McKesson Radiology ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Properties of the Study Lists .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Customizing the Study Lists ................................................................................................................................................... 13 Custom Filters ........................................................................................................................................................................ 14 Chapter 4 – Rad Report ............................................................................................................................................................. 17 What is Rad Report -

Fiery Ticker © 2017 Electronics for Imaging, Inc

Fiery Ticker © 2017 Electronics For Imaging, Inc. The information in this publication is covered under Legal Notices for this product. 17 April 2017 Fiery Ticker 3 Contents Contents Fiery Ticker ..................................................................................5 Status bar for Fiery Ticker ..........................................................................5 Full-screen view for Fiery Ticker ....................................................................5 Use Fiery Ticker shortcuts .........................................................................6 Change the Fiery Ticker display .....................................................................6 Switch between the status bar and full-screen views in Fiery Ticker ......................................6 Show or hide the Fiery Ticker status bar ............................................................7 Use Fiery Notes ..................................................................................7 Create a note in Fiery Notes ......................................................................7 Edit, move, or delete a note ......................................................................7 Configure Fiery Ticker ............................................................................7 Motion detection with the proximity sensor on the Fiery NX Station LS ....................................8 Fiery Ticker 4 Contents Fiery Ticker 5 Fiery Ticker Fiery Ticker Fiery Ticker is a status interface for the Fiery server that appears on the display -

Ohio Online Science and Social Studies Practice Tests Guidance Document Published October 2, 2014

Ohio Online Science and Social Studies Practice Tests Guidance Document Published October 2, 2014 This document covers the following information: About the Practice Tests Signing Into the Practice Tests and Selecting Accessibility Features Student Practice Site o Toolbar Overview o Navigation o Items that Are Part of a Cluster o Test Progress Indicator o Toolbar Buttons o Item Features and Additional Tools o Performance-Based Assessment Writing Tools o Text-to-Speech and Text-to-Speech Tracking o Ending the Test About the Practice Tests Online practice tests for the seven science and social studies tests that will be administered in spring 2015 are available on the Ohio Computer Based Assessments Portal (oh.portal.airast.org/ocba). The Practice Tests link is available in the right column. For each spring test, a performance-based assessment (PBA) practice test and an end-of-year (EOY) practice test are available. The practice tests have approximately half as many items as operational tests. Do not assume the operational test will include exactly twice as many items. Items selected for the Ohio online science and social studies practice tests allow students to practice with different types of online test item types. Students will see the types of questions that could be on a science or social studies test, and can review sample test content. Additionally, the practice tests give students the opportunity to navigate through the online testing system, use the available tools and features, and familiarize themselves with the testing experience. For educators, the practice tests provide an opportunity to review examples of how the performance-based assessment (PBA) and end-of-year (EOY) test may assess Ohio’s New Learning Standards for science and social studies. -

Motion Detection

CONTENTS About This User’s Guide ............................................................................................................... iv Before You Start ............................................................................................................................ iv Packing List ................................................................................................................................... iv System Requirements .................................................................................................................... v Default Settings ............................................................................................................................. vi INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 7 Features and Benefits .................................................................................................................... 7 Camera Hardware Components ..................................................................................................... 8 Front Panel Components ............................................................................................................... 8 LED Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 8 Rear Panel Components ................................................................................................................ 9 Rear Panel Components -

• Graphical User Interfaces • Pre-Historic Times

GUI GUIs • Graphical User Interfaces – windows/menus/controls – mouse/keyboard 1 Timeline GUIs • Pre-historic times – Douglas Engelbart, Stanford, 1962 - 1968 • 1st “mouse”: wooden box on wheels – Ivan Sutherland, MIT, 1963 • Sketchpad 2 1 Timeline GUIs Sketchpad: Ivan Sutherland, MIT, 1963 – Create engineering drawings (2000 : 1 scale) – Ran on experimental “online” computer – Physically huge due to 320 KB memory – CRT, light pen – First GUI – New concepts: rubber-banding, zoom in/out, sketching perfect lines, corners, and joints. 3 Sketchpad GUIs 4 2 Engelbart 1968 GUIs • Demo: mouse, text editing, copy/paste, etc. RealVideo clip: http://sloan.stanford.edu/mousesite/1968Demo.html 5 Xerox PARC: Alto computer, 1975 GUIs Features: • 8½ x 11 Bit-mapped display (WYSIWYG) • Windows, icons, menus, pointer (WIMP) • Ethernet… 6 3 Timeline GUIs • 1979: Jobs and Wozniak visit PARC • June 1981: Xerox Star – Double-clickable icons – Overlapping windows – Dialog boxes – 1024x768 monochrome display – High price 7 Timeline GUIs • January 1983 – Apple’s Lisa • pull down menus • menu bars – Microsoft announces Windows • supposedly has overlapping/resizable windows 8 4 Apple Lisa GUIs Introduced: January 1983 Released: June 1983 Price: US $9,995 How many? 100,000 in two years CPU: Motorola 68000, 5 MHz RAM: 1 Meg Display: 12" monochrome, 720 X 364 9 1984 GUIs • January 1984 – Apple’s Macintosh – 128Kb memory – $2,495.00. • June 1984 – X windows (MIT) – Customizable 10 5 August 1985: MS Windows ships GUIs • Windows can be tiled, not overlapped • Iconized