Breaking the Cycle of Recurrent Fracture in Patients with Osteoporosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

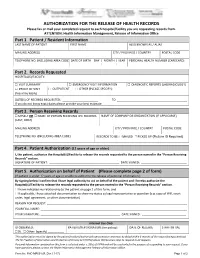

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. -

It's Our Emergency

IT’S OUR EMERGENCY. Let’s Work TogethER. PEACE ARCH HOSPITAL’S CAMPAIGN FOR A NEW ER e-mer-gen-cy: (noun) a sudden, urgent, usually unexpected occurrence or occasion requiring immediate action. Ready or not, here you come. Accidents or unforeseen health issues can happen to any of us at anytime. No one starts their day anticipating a visit to their local Emergency Department — yet we all want the ER to be ready when we are. But the needs of our growing community have outgrown our current ER. Built in 1989 to accommodate 20,000 patients annually, it is now too small and poorly configured to effectively and safely manage the 50,000 patients treated last year and the 70,000 forecasted in the future. Every day, the remarkable ER team works with skill, diligence and heart to accommodate every patient and every family in circumstances that have gone from challenging to unbearable. Our Emergency Department is in its own state of emergency. A new Emergency Department with increased capacity, appropriate dedicated treatment spaces and improved patient flow, safety and security, is central to Peace Arch Hospital’s site Redevelopment + Expansion. The Ministry of Health has committed $5 million of the estimated $20 million needed to build the new ER. Peace Arch Hospital & Community Health Foundation needs our help to raise the additional $15 million for an ER capable of meeting the diverse needs of our growing community … for the staff who work there, and for every patient and every family who arrive unexpectedly, every day. One day ‘they’ will be ‘you’. -

Births by Facility 2015/16

Number of Births by Facility British Columbia Maternal Discharges from April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016 Ü Number of births: Fort Nelson* <10 10 - 49 50 - 249 250 - 499 500 - 999 Fort St. John 1,000 - 1,499 Wrinch Dawson Creek 1,500 - 2,499 Memorial* & District Mills Chetwynd * ≥ 2,500 Memorial Bulkley Valley MacKenzie & 1,500-2,499 Stuart Lake Northern Prince Rupert District * Births at home with a Haida Gwaii* University Hospital Registered Healthcare Provider of Northern BC Kitimat McBride* St. John G.R. Baker Memorial Haida Gwaii Shuswap Lake General 100 Mile District Queen Victoria Lower Mainland Inset: Cariboo Memorial Port Golden & District McNeill Lions Gate Royal Invermere St. Paul's Cormorant Inland & District Port Hardy * Island* Lillooet Ridge Meadows Powell River Vernon VGH* Campbell River Sechelt Kootenay Elk Valley Burnaby Lake Squamish Kelowna St. Joseph's General BC Women's General Surrey Penticton Memorial West Coast East Kootenay Abbotsford Royal General Regional Richmond Columbian Regional Fraser Creston Valley Tofino Canyon * Peace Langley Nicola General* Boundary* Kootenay Boundary Arch Memorial Nanaimo Lady Minto / Chilliwack Valley * Regional Gulf Islands General Cowichan Saanich District Victoria 0 62.5 125 250 375 500 Peninsula* General Kilometers * Hospital does not offer planned obstetrical services. Source: BC Perinatal Data Registry. Data generated on March 24, 2017 (from data as of March 8, 2017). Number of Births by Facility British Columbia, April 1, 2015 - March 31, 2016 Facility Community Births 100 Mile -

Carms 2021 Information Package TABLE of CONTENTS

THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHIATRY CaRMS 2021 Information Package TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 Welcome Messages 05 Program Overview 06 Clinical Curriculum 13 Psychotherapy Curriculum 14 Academic Curriculum 15 Opportunities Unique to UBC 16 Outreach and Rural Practice Opportunities 17 Fellowship & Subspecialty Training 18 CaRMS Interview Day QUESTIONS ABOUT INTERVIEW SCHEDULE? CONTACT: Linda Chang Education Coordinator, PGE [email protected] Welcome Message from Dr. Khanbhai Irfan Khanbhai Interim Program Director [email protected] Dear CaRMS Applicant, I am excited that you have chosen UBC Psychiatry for an interview. I look forward to meeting you during the interview period as I meet with all applicants individually. UBC Psychiatry offers a dynamic and comprehensive program. Depending on what track you have applied to, I encourage you to read the information outlined in the document. I am from North Vancouver, received my BSc from McGill, completed medical school at UBC, and thereafter, began my training in Psychiatry at UBC. Given that I have trained here, I can say first hand that we offer an incredible program with respect to clinical experience and resident education. I have been involved in resident education since my residency training and feel privileged to be able to lead this program. Please feel free to email me at [email protected]. Sincerely, Irfan Khanbhai Interim Program Director University of British Columbia Postgraduate Education Psychiatry 3 Message from our CaRMS Committee Dear CaRMS Applicant, We would like to welcome you (virtually!) to the University of British Columbia! Our program offers a diverse array of exceptional training in all core competencies outlined by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. -

Capital Project Plan Peace Arch Hospital Renewal Project March 2017

Capital Project Plan Peace Arch Hospital Renewal Project March 2017 1. Project Background In 2012 the Peace Arch Hospital Master Concept Plan was prepared by Fraser Health (FH) through Lower Mainland Facilities Management (LMFM) and in partnership with PAH site leadership and the Peace Arch Hospital & Community Health Foundation (the Foundation). The Master Concept Plan created a 20-year vision for the site and outlined a 10-year site development plan for the immediate and longer-term clinical service delivery requirements. Two of the short-term priorities called for facility improvements and service capacity expansion for Emergency services and Surgical services. A PAH Emergency Department Renovation & Expansion business plan was completed in 2013 and approved by government in December, 2014. As the Emergency Department project was advancing, an Accreditation Canada review of the PAH Medical Device Reprocessing (MDR) department and a Surgical services review at PAH revealed escalating needs for facilities improvements. Subsequent planning for the MDR and Surgical services explored options for accommodation of these services and site studies concluded that the planned building expansion for the new ED offered the best opportunity for a cost-effective, long-term solution for MDR and Surgical services. In 2016 the approved Emergency Department project was revisited and expanded to make the case for a broader facility solution for Emergency services, MDR, and Surgical services. The resulting PAH Renewal Business Plan documented the case for an integrated and comprehensive facility solution to accommodate an expanded Emergency department, a new MDR department, and a new Perioperative Suite to support Surgical service delivery. This Project provides a cost-effective, long-term strategy for PAH to effectively resolve safety issues impacting patient care, increase surgical and emergency capacity to meet current and future demand, and substantially improve building deficiencies. -

Induction of Labour When Labour Needs to Be Started

Induction of labour When labour needs to be started For most women labour starts on its own. For some Why would labour be induced? women, labour needs help to get started. Times when we consider inducing labour: ‘Induction’ is when we start or ‘induce’ labour for Your pregnancy is 7 days or more past your you. This is usually done when your doctor or due date. midwife (care provider) feels the risks to you or The bag of water around the baby breaks your baby are greater than the risk of carrying on before labour starts. with the pregnancy. Your baby is growing too slowly. Induction of labour is generally safe. However, as The fluid around the baby is low. with any medical procedure or medicine, there are possible risks. Your care provider will explain You have a medical illness (such as high blood these to you. pressure, or diabetes) that might affect you or your baby’s health. How is labour induced? . Prostaglandin Gel . Oxytocin This medicated gel is put into your vagina. It We give this medication into a vein in your arm. softens the cervix and helps start contractions. This is called an intravenous (or IV). You stay in We observe you and your baby for at least 1 the hospital until your baby is born. We check hour. You stay in bed for the hour to make sure you and your baby often during this time. the gel has time to absorb. You will not be able to . Breaking the water sac (rupturing the membranes) eat or drink during this time. -

Breast Biopsy Limit Any Arm Strain on the Side You Had Jim Pattison Outpatient Care 604-533-3308 the Biopsy

Care at home Locations Abbotsford-Regional Hospital 604-851-4868 Your breast will be tender and a little Medical Imaging 2nd Floor, Fraser Wing, 32900 Marshall Road, Abbotsford swollen. You might get a bruise at the BC Cancer Agency 604-877-6000 needle site. This is normal and should go Medical Imaging, 3rd Floor, 600 West 10th Ave, Vancouver Chilliwack General Hospital 604-795-4122 away within a few days. Medical Imaging, Main Floor, 45600 Menholm Rd, Chilliwack Return to your regular daily activities. Delta Hospital 604-946-1121 Medical Imaging, 5800 Mountain View Boulevard, Delta Breast Biopsy Limit any arm strain on the side you had Jim Pattison Outpatient Care 604-533-3308 the biopsy. and Surgery Centre ext. 63926 Medical Imaging, 2nd Floor, 9750 140th Street, Surrey Langley Memorial Hospital 604-533-6405 For the next 24 hours: Medical Imaging, Main Floor, 22051 Fraser Highway, Langley Wear a supportive bra. Lions Gate Hospital 604-984-5775 Place an ice pack over your bra on the Medical Imaging, Lower Level, 231 East 15th Street, North Vancouver needle site for 10 to 15 minutes at a Mount Saint Joseph Hospital 604-877-8323 Medical Imaging, Level one, 3080 Prince Edward Street, Vancouver time. Peace Arch Hospital 604-531-5512 If needed, take plain acetaminophen Medical Imaging, Main Floor, 15521 Russell Ave, White Rock (Tylenol) for pain. Powell River General Hospital 604-485-3282 Medical Imaging, 5000 Joyce Avenue, Powell River Richmond Hospital 604-278-9711 Medical Imaging, Main Floor, 7000 Westminster Hwy, Richmond When to get help Ridge Meadows Hospital 604-463-1800 Call your doctor if you have: Medical Imaging, Main Floor, 11666 Laity St., Maple Ridge Fever above 38.5°C (101°F), aches and Royal Columbian Hospital 604-520-4640 Medical Imaging, Columbia Tower, 330 E. -

PATH Unit Patient Assessment and Transition to Home

What you will need to bring: PATH Units in Fraser Health Appropriate footwear/street clothes Abbotsford Regional Hospital Toothbrush/Toothpaste/Denture 604 - 851-4849 cleaner / Shaving equipment Comb / Brush / Deodorant Burnaby Hospital 604 - 434-4211 Personal unscented creams or lotions Chilliwack General Hospital 604-795-4141 Special pillow or blanket Delta Hospital 604-946-1121 When you leave PATH Eagle Ridge Hospital PATH Unit The team will plan with you and 604-461-2022 your family for your return to home or community. Langley Memorial Hospital 604-534-4121 Patient Assessment You should ensure you have the and Transition following with you: Peace Arch Hospital 604 - 531-5512 All personal items to Home Medications from home and Queen’s Park Care Centre 604-519-8561 new prescriptions Dates and referrals for follow- Ridge Meadows Hospital 604-463-1822 up appointments You or your family are responsible Print Shop # 256155 for making follow-up appointments. PATH – Patient Assessment and Transition to Home PATH Working Together The PATH Team….. The PATH team is here to help The PATH unit will provide an You and your family you improve your ability to environment that promotes your Physician manage your care needs as strengths and abilities. The team Patient Care Coordinator independently as possible to will work with you and your family Quick Response Case Manager assist you in your transition to to develop a plan for your care Nursing Staff home or community. that is based on your needs. Care Aides Physiotherapist The team will keep you and your In order to maintain your well- Rehabilitation Assistant family informed of your care, being, the PATH team will Occupational Therapist share information, or review any encourage you to: Social Worker appropriate discharge planning. -

Diagnostic Imaging

DIAGNOSTIC ACCREDITATION PROGRAM College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia 300–669 Howe Street Telephone: 604-733-7758 Vancouver BC V6C 0B4 Toll free: 1-800-461-3008 (in BC) www.cpsbc.ca Fax: 604-733-3503 Accredited Facilities – Diagnostic Imaging As of 2021-09-20 Facility Name Address Scope of Expiry Date Organization Medical Director Accreditation of Accreditation 100 Mile District General Hospital 555 Cedar Drive Radiology 2023-04-19 Interior Health Authority Dr. Vipal Vedd 100 Mile House, BC, V0K 2E0 Abbotsford MRI Clinic Suite 5 - 2151 McCallum Road Magnetic Resonance 2024-09-04 Fraser Health Authority Dr. Amarjit Bajwa Abbotsford, BC, V2S 3N8 Imaging Abbotsford Regional Hospital and 32900 Marshall Road Radiology, Ultrasound, 2024-02-27 Fraser Health Authority Dr. Amarjit Bajwa Cancer Centre Abbotsford, BC, V2S 1K2 Computed Tomography, Nuclear Medicine, Mammography, Echocardiography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Bone Densitometry Abbotsford Regional Hospital and 32900 Marshall Road Vascular Ultrasound - 2025-12-17 Fraser Health Authority Dr. Husain Khambati Cancer Centre - Vascular Lab Abbotsford, BC, V2S 0C2 Limited Scope Aberdeen Ultrasound and X-Ray 272 - 1320 W. Trans Canada Hwy Radiology, Ultrasound 2025-02-05 Aberdeen Ultrasound Dr. Micheal Burns Kamloops, BC, V1S 1J2 and X-Ray Access MRI 104 - 15137 56 Avenue Magnetic Resonance 2026-02-10 Access MRI Dr. Spencer Lister Surrey, BC, V3S 9A5 Imaging, Ultrasound, Echocardiography AIM Medical Imaging Inc. 1371 West Broadway Magnetic Resonance 2024-10-24 AIM Medical Imaging Dr. Raj Attariwala Vancouver, BC, V6H 1G9 Imaging Inc. Arrow Lakes Hospital 97 1st Avenue NE Radiology 2023-04-10 Interior Health Authority Dr. -

In Action Auxiliary

Auxiliary In Action OCTOBER 2019 Marilyn Van Iderstine, Editor COMING EVENTS President’s Message (Members Meeting Wed Oct 2, 2019) October 18 Semiahmoo Bake Sale in cafeteria In June we had an emergency request from the Oct 22 Aquarius Pizza night hospital to fund Orthopaedic tools. The hospital Oct 25 Les Papillons Fall had received a directive from Fraser Health on Bridge Luncheon at St Mark’s June 3, 2019 by way of the Ministry of Health that Anglican church the hospital had to increase the number of knee and hip surgeries and replacements to alleviate the Nov 9 Kwatcha Linen Sale at backlog and waiting times. The total cost to Ocean Park Community Hall upgrade and purchase extra equipment was Nov 19 Aquarius jewelry $282,000.00. Fraser Health would fund up to a maximum of $191,000.00 and the shortfall was $98,930.00 which the hospital had Sale in Cafeteria to fund via their operating budget. This would be a hardship for the Dec 15 Kay Hogg Goodwill— hospital as it would mean the possibility of other programs being Joy of Music Orpheus Choir cancelled or reduced funding to make up the funds required. The concert at Mount Olive Auxiliary and the Foundation were asked if we could help with this Lutheran Church funding. We had a surplus of $22,886.29 left over from the approved expenditure of $351,000.00 from the 2018/19 equipment list as some equipment items came in under budget. The Board agreed to fund the Executive orthopaedic equipment requested up to $22,886.00. -

Learn More Icon Spring 2020

SPRING 2020 PEACE ARCH HOSPITAL FOUNDATION Special Edition NOT ALL HEROES WEAR CAPES HOW THE FRONTLINE STAFF AT PEACE ARCH HOSPITAL ARE TACKLING THE COVID-19 CRISIS LEADING THE WAY WELCOME TO OUR NEWEST EDITION OF thrive To say that these last three months have been challenging would be an understatement. No one could have predicted that when the calendar flipped over to 2020 that it would be a year like no other. Nowhere in our community has this been more transparent than at Peace Arch Hospital. From the first days of the COVID-19 crisis, our medical staff and administrators stepped up to ensure our hospital was prepared for whatever walked through our doors. Our community has also rallied around our hospital, just like they did back in 1948 when Peace Arch was merely a dream and small, grassroots fundraisers made it a reality. That spirit Janice Stasiuk of giving is still thriving more than 70 years later. Whether it’s providing nourishing meals for our frontline health care heroes who are working day and night to keep us safe and well, or funding iPads so our most fragile and vulnerable long-term care residents can communicate with their loved ones during this time of restricted visiting, our community has once again opened their hearts and wallets and for that we are eternally grateful. You’ll find some inspiring stories in these pages of how our medical team is navigating these uncharted waters along with how your gifts have made an impact with our Rapid Response Grants, which provide quick financial assistance to non-profit organizations offering programs, services, and activities that aid our community during this crisis. -

Vancouver- Fraser

DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY MEDICINE VANCOUVER - FRASER RESIDENCY SITE OVERVIEW • Urban, suburban program based at the Royal Columbian Hospital with rotations throughout the Fraser Valley • Focus on full-service family medicine • Flexible in meeting individual training goals • Block-based scheduling • Diverse training sites including community and tertiary hospitals VANCOUVER - FRASER TRAINING SITES FIRST YEAR SCHEDULE 4 week blocks, 13 blocks per academic year • 16 weeks Family Practice • 12 weeks Internal Medicine • 8 weeks Obstetrics • 8 weeks Pediatrics • 4 weeks General Surgery • 4 weeks Emergency Medicine FAMILY MEDICINE • 4 Blocks (16 weeks) • Choice of two well-established teaching sites - Family Practice Centre (Fairmont Medical Building) - UBC Family Practice Centre • Up to 1.5 days per week as horizontal electives • Home call ~1 in 4, option to cover Obstetrics call • One (1) full-day callback every second week during non-block time • Dedicated Family physician experts in Sports, Maternity and Behavioral Medicine OBSTETRICS/ GYNECOLOGY • 2 blocks (8weeks) • Choice of 2 sites: - Royal Columbian Hospital - Peace Arch Hospital • In-house call, ~1 in 4 • Numerous opportunities to learn low-risk maternity from experienced GPs and Obstetricians PEDIATRICS 2 Blocks (8 weeks) 2-4 weeks at BCCH Emergency 2-4 weeks of: Ambulatory Peds, Urgent Care, Intermediate Nursery or NICU INTERNAL MEDICINE • 3 Blocks (12 weeks) (1)CTU - Royal Columbian Hospital (4 weeks) (2)Internal Medicine- Mount St. Joseph Hospital OR Burnaby General Hospital (4 weeks) (3)Hospitalist- Mount St. Joseph Hospital OR Royal Columbian Hospital • Exposure to ICU at Burnaby General Hospital • Variety of specialty outpatient clinics - Diabetes, Cardiology, Respirology, Neurology • In-house call*, ~1 in 4 *CTU & IM MSJ HOSPITALIST • 1 Block (4 weeks) • Mount St.