The Systematics, Biology, and Conservation of Solenodon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informe De Ejecución Febrero, 2021

Informe de ejecucIón feBrero, 2021 Elaborado por: Subdirección Técnica Durante el mes de febrero 2021, esta institución ha mantenido todos los niveles de seguridad y ha cumplido con las medidas tomadas por nuestras autoridades para proteger nuestros colaboradores y productores, pero aun así se realizaron actividades puntuales para dar cumplimiento a los objetivos trazados como institución y a los acuerdos sostenidos, de las cuales detallamos las más relevantes a continuación: 1. PRODUCCION PLANTAS SEMBRADAS 606,480 TAREAS FOMENTADAS 312 TAREAS RENOVADAS 2,348.32 Hombres:111 BENEFICIARIOS Mujeres:3 114 COSECHAS 62,325 QQS febrero, 2021 (QQS) COSECHAS A LA FECHA 158, 115 QQS (QQS) UBICACIÓN DE LA SIEMBRA DE CAFÉ EN FOMENTO Y RENOVACIÓN Mes: Febrero Regional Paraje Área Cafetalera Municipio Provincia Las Yaguas Iguana/La laguna Baní Peravia El Hoyito Iguana/La laguna Baní Peravia Central Firme del Barro Recodo Baní Peravia Yuna Yuna Rancho Arriba San José de Ocoa La Peñita Yuna Rancho Arriba San José de Ocoa Cabia Navas Santiago Santiago El Cabismal La Lomota Navarrete Santiago Las Placetas Las Placetas Sajoma Santiago Norte Franco Bidó Juncalito Jánico Santiago Loma Prieta Juncalito Jánico Santiago Los Arroyos Juncalito Jánico Santiago El 31 Palma Picada Esperanza Valverde Vista Alegre Paradero Esperanza Valverde La Cabirma Paradero Esperanza Valverde Noroeste Paradero Paradero Esperanza Valverde Alto de la Paloma Mariano Cestero Loma de Cabrera Dajabón Mochito Los Cerezos Restauración Dajabón Nordeste Los guayuyos Naranjo Dulce San Francisco -

Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 Secretary General César Gaviria

Electoral Observations in the Americas Series, No. 13 Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 Secretary General César Gaviria Assistant Secretary General Christopher R. Thomas Executive Coordinator, Unit for the Promotion of Democracy Elizabeth M. Spehar This publication is part of a series of UPD publications of the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States. The ideas, thoughts, and opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the OAS or its member states. The opinions expressed are the responsibility of the authors. OEA/Ser.D/XX SG/UPD/II.13 August 28, 1998 Original: Spanish Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 General Secretariat Organization of American States Washington, D.C. 20006 1998 Design and composition of this publication was done by the Information and Dialogue Section of the UPD, headed by Caroline Murfitt-Eller. Betty Robinson helped with the editorial review of this report and Jamel Espinoza and Esther Rodriguez with its production. Copyright @ 1998 by OAS. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced provided credit is given to the source. Table of contents Preface...................................................................................................................................vii CHAPTER I Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER II Pre-election situation .......................................................................................................... -

Quantifying Arbovirus Disease and Transmission Risk at the Municipality

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.20143248; this version posted July 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 1 Title: Quantifying arbovirus disease and transmission risk at the municipality 2 level in the Dominican Republic: the inception of Rm 3 Short title: Epidemic Metrics for Municipalities 4 Rhys Kingston1, Isobel Routledge1, Samir Bhatt1, Leigh R Bowman1* 5 1. Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Imperial College London, UK 6 *Corresponding author 7 [email protected] 8 9 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. 1 medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.20143248; this version posted July 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 2 10 Abstract 11 Arboviruses remain a significant cause of morbidity, mortality and economic cost 12 across the global human population. Epidemics of arboviral disease, such as Zika 13 and dengue, also cause significant disruption to health services at local and national 14 levels. This study examined 2014-16 Zika and dengue epidemic data at the sub- 15 national level to characterise transmission across the Dominican Republic. -

21 Blue Flags for the Best Beaches in the Caribbean and Latin America

1. More than six million people arrived to the Dominican Republic in 2015 2. Dominican Republic: 21 blue flags for the best beaches in the Caribbean and Latin America 3. Dominican Republic Named Best Golf Destination in Latin America and the Caribbean 2016 4. Dominican Republic Amber Cove is the Caribbean's newest cruise port 5. Dominican Republic Hotel News Round-up 6. Aman Resorts with Amanera, Dominican Republic 7. Hard Rock International announces Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Santo Domingo 8. New Destination Juan Dolio, Emotions By Hodelpa & Sensations 9. New flight connections to the Dominican Republic 10. Towards the Caribbean sun with Edelweiss 11. Whale whisperer campaign wins Gold medal at the FOX awards 2015 12. Dominican Republic – the meetings and incentive paradise 13. Activities and places to visit in the Dominican Republic 14. Regions of the Dominican Republic 15. Dominican Republic Calendar of Events 2016 1. More than six million people arrived to the Dominican Republic in 2015 The proportion of Germans increased by 7.78 percent compared to 2014 Frankfurt / Berlin. ITB 2016. The diversity the Dominican Republic has to offer has become very popular: in 2015, a total of 6.1 million arrivals were recorded on this Caribbean island, of which 5.6 million were tourists – that is, 8.92 percent up on the previous year. Compared to 2014 the proportion of Germans increased by 7.78 percent in 2015. Whereas in 2014, a total of 230,318 tourists from the Federal Republic visited the Dominican Republic, in 2015 248,248 German tourists came here. Furthermore, a new record was established in November last year: compared to the same period in the previous year, 19.8 percent more German tourists visited the Caribbean island. -

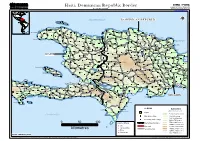

Haiti, Dominican Republic Border Geographic Information and Mapping Unit As of February 2004 Population and Geographic Data Section Email : [email protected]

GIMU / PGDS Haiti, Dominican Republic Border Geographic Information and Mapping Unit As of February 2004 Population and Geographic Data Section Email : [email protected] ATLANTIC OCEAN DOMINICANDOMINICAN REPUBLICREPUBLIC !!! Voute I Eglise ))) ))) Fond Goriose ))) ))) ))) Saint Louis du Nord ))) ))) ))) ))) Cambronal Almaçenes ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Monte Cristi ))) Jean Rabel ))) ))) Bajo Hondo ))) ))) ))) Gélin ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Sabana Cruz ))) La Cueva ))) Beau Champ ))) ))) Haiti_DominicanRepBorder_A3LC Mole-Saint-Nicolas ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Bassin ))) Barque ))) Los Icacos ))) ))) Bajo de Gran Diablo )))Puerto Plata ))) Bellevue ))) Beaumond CAPCAPCAP HAITIEN HAITIENHAITIEN ))) Palo Verde CAPCAPCAP HAITIEN )HAITIEN)HAITIEN) ))) PUERTOPUERTOPUERTO PLATA PLATAPLATA INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL ))) ))) Bambou ))) ))) Imbert ))) VVPUERTOPUERTOPUERTO))) PLATA PLATAPLATA INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL VV ))) VV ))) ))) ))) VV ))) Sosúa ))) ))) ))) Atrelle Limbé VV ))) ))) ))) ))) VV ))) ))) ))) ))) VV ))) ))) ))) Fatgunt ))) Chapereau VV Lucas Evangelista de Peña ))) Agua Larga ))) El Gallo Abajo ))) ))) ))) ))) Grande Plaine Pepillo Salcedo))) ))) Baitoa ))) ))) ))) Ballon ))) ))) ))) Cros Morne))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Sabaneta de Yásica ))) Abreu ))) ))) Ancelin ))) Béliard ))) ))) Arroyo de Leche Baie-de-Henne ))) ))) Cañucal ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) La Plateforme ))) Sources))) Chaudes ))) ))) Terrier Rouge))) Cacique Enriquillo ))) Batey Cerro Gordo ))) Aguacate del Limón ))) Jamao al Norte ))) ))) ))) Magante Terre Neuve -

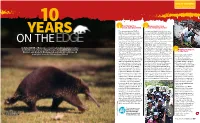

EDGE of EXISTENCE 1Prioritising the Weird and Wonderful 3Making an Impact in the Field 2Empowering New Conservation Leaders A

EDGE OF EXISTENCE CALEB ON THE TRAIL OF THE TOGO SLIPPERY FROG Prioritising the Empowering new 10 weird and wonderful conservation leaders 1 2 From the very beginning, EDGE of Once you have identified the animals most in Existence was a unique idea. It is the need of action, you need to find the right people only conservation programme in the to protect them. Developing conservationists’ world to focus on animals that are both abilities in the countries where EDGE species YEARS Evolutionarily Distinct (ED) and Globally exist is the most effective and sustainable way to Endangered (GE). Highly ED species ensure the long-term survival of these species. have few or no close relatives on the tree From tracking wildlife populations to measuring of life; they represent millions of years the impact of a social media awareness ON THE of unique evolutionary history. Their campaign, the skill set of today’s conservation GE status tells us how threatened they champions is wide-ranging. Every year, around As ZSL’s EDGE of Existence conservation programme reaches are. ZSL conservationists use a scientific 10 early-career conservationists are awarded its first decade of protecting the planet’s most Evolutionarily framework to identify the animals that one of ZSL’s two-year EDGE Fellowships. With Making an impact are both highly distinct and threatened. mentorship from ZSL experts, and a grant to set in the field Distinct and Globally Endangered animals, we celebrate 10 The resulting EDGE species are unique up their own project on an EDGE species, each 3 highlights from its extraordinary work animals on the verge of extinction – the Fellow gains a rigorous scientific grounding Over the past decade, nearly 70 truly weird and wonderful. -

2714 Surcharge Supp Eng.V.1

Worldwide Worldwide International Extended Area Delivery Surcharge ➜ Locate the destination country. ➜ Locate the Postal Code or city. ➜ If the Postal Code or city is not listed, the entry All other points will apply. ➜ A surcharge will apply only when a “Yes” is shown in the Extended Area Surcharge column. If a surcharge applies, add $30.00 per shipment or $0.30 per pound ($0.67 per kilogram), whichever is greater, to the charges for your shipment. COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE ARGENTINA BOLIVIA (CONT.) BRAZIL (CONT.) CHILE (CONT.) COLOMBIA (CONT.) COLOMBIA (CONT.) DOMINICAN REPUBLIC (CONT.) DOMINICAN REPUBLIC (CONT.) 1891 – 1899 Yes Machacamarca Yes 29100 – 29999 Yes El Bosque No Barrancabermeja No Valledupar No Duarte Yes Monte Plata Yes 1901 – 1999 Yes Mizque Yes 32000 – 39999 Yes Estación Central No Barrancas No Villa de Leiva No Duverge Yes Nagua Yes 2001 – 4999 Yes Oruro Yes 44471 – 59999 Yes Huachipato No Barranquilla No Villavicencio No El Cacao Yes Neiba Yes 5001 – 5499 Yes Pantaleón Dalence Yes 68000 – 68999 Yes Huechuraba No Bogotá No Yopal No El Cercado Yes Neyba Yes 5501 – 9999 Yes Portachuelo Yes 70640 – 70699 Yes Independencia No Bucaramanga -

Independent Evolutionary Histories in Allopatric Populations of a Threatened Caribbean Land Mammal

Article type: Biodiversity Research Independent evolutionary histories in allopatric populations of a threatened Caribbean land mammal Samuel T. Turvey1, Stuart Peters2*, Selina Brace3*, Richard P. Young4, Nick Crumpton3,5, James Hansford1,6, Jose M. Nuñez-Miño4, Gemma King7, Katrina Tsalikidis7, José A. Ottenwalder8, Adrian Timpson9, Stephan M. Funk10,11, Jorge L. Brocca12, Mark G. Thomas2 and Ian Barnes3 1Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY, UK, 2Research Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK, 3Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK, 4Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Les Augrès Manor, Trinity, Jersey JE3 5BP, Channel Islands, 5Research Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK, 6Ocean and Earth Science, National Oceanography Centre Southampton, University of Southampton Waterfront Campus, European Way, Southampton, UK, 7School of Biological Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham Hill, Egham TW20 OEX, UK, 8Mahatma Gandhi 254, Gazcue, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 9Institute of Archaeology, University College London, Gordon Square, London WC1H 0PY, UK, 10Nature Heritage, St. Lawrence, Jersey, Channel Islands, 11Universidad de Temuco UCT, Casilla 15-D, Rudecindo Ortega 02950, Temuco, Chile, 12Sociedad Ornitológica de la Hispaniola, Parque Zoologico Nacional, Avenida de la Vega Real, Arroyo Hondo, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic *Correspondence: [email protected], [email protected] Running title: Evolutionary history of Hispaniolan solenodon populations 1 ABSTRACT Aim To determine the evolutionary history, relationships and distinctiveness of allopatric populations of Hispaniolan solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus), a highly threatened Caribbean “relict” mammal, to understand spatiotemporal patterns of gene flow and the distribution of diversity across complex large island landscapes and inform spatial conservation prioritization. -

Dominican Republic

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF DOMINICAN REPUBLIC By Ivette E. Torres The economy of the Dominican Republic grew by 4.8% in Production of gold in 1995 from Rosario Dominicana real terms in 1995 according to the Central Bank. But S.A.’s Pueblo Viejo mine increased almost fivefold from that inflation was 9.2%, an improvement from that of 1994 when of 1994 to 3,288 kilograms after 2 years of extremely low inflation exceeded 14%. The economic growth was production following the mine's closure at the end of 1992. stimulated mainly by the communications, tourism, minerals, The mine reopened in late 1994. commerce, transport, and construction sectors. According to During the last several decades, the Dominican Republic the Central Bank, in terms of value, the minerals sector has been an important world producer of nickel in the form increased by more than 9%.1 of ferronickel. Ferronickel has been very important to the During the year, a new law to attract foreign investment Dominican economy and a stable source of earnings and was being considered by the Government. The law, which Government revenues. In 1995, Falcondo produced 30, 897 would replace the 1978 Foreign Investment Law (Law No. metric tons of nickel in ferronickel. Of that, 30,659 tons 861) as modified in 1983 by Law No. 138, was passed by was exported, all to Canada where the company's ferronickel the Chamber of Deputies early in the year and was sent to the was purchased and marketed by Falconbridge Ltd., the Senate in September. The law was designed to remove company's majority shareholder. -

Situation Report 2 –Tropical Storm Olga – DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 14 DECEMBER 2007

Tropical Storm Olga Dominican Republic Situation Report No.2 Page 1 Situation Report 2 –Tropical Storm Olga – DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 14 DECEMBER 2007 This situation report is based on information received from the United Nations Resident Coordinators in country and OCHA Regional Office in Panama. HIGHLIGHTS • Tropical Storm Olga has claimed the lives of 35 people. Some 49,170 persons were evacuated and 3,727 are in shelters. • Needs assessments are ongoing in the affected areas to update the Noel Flash Appeal. SITUATION 5. The Emergency Operations Centre (COE) is maintaining a red alert in 30 provinces: Santo 1. Olga developed from a low-pressure system into a Domingo, Distrito Nacional, San Cristóbal, Monte named storm Monday 10 December, although the Plata, Santiago Rodríguez, Dajabón, San Pedro de Atlantic hurricane season officially ended November Macorís, Santiago, Puerto Plata, Espaillat, Hermanas 30. The centre of Tropical Storm Olga passed Mirabal (Salcedo), Duarte (Bajo Yuna), María through the middle of the Dominican Republic Trinidad Sánchez, Samaná, Montecristi, Valverde- overnight Tuesday to Wednesday on a direct Mao, Sánchez Ramírez, El Seibo, La Romana, Hato westward path. Olga has weaken to a tropical Mayor (in particular Sabana de la Mar), La depression and moved over the waters between Cuba Altagracia, La Vega, Monseñor Nouel, Peravia, and Jamaica. The depression is expected to become a Azua, San José de Ocoa, Pedernales, Independencia, remnant low within the next 12 hours. San Juan de la Maguana and Barahona. Two provinces are under a yellow alert. 2. Olga is expected to produce additional rainfall, accumulations of 1 to 2 inches over the southeastern Impact Bahamas, eastern Cuba, Jamaica and Hispaniola. -

Ecologia De Les Illes

Observations on the habitat and ecology of the Hispaniolan Solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus) in the Dominican Republic Jose A. OTTENWALDER Proyecto Biodiversidad GEF-PNUD/ONAPLAN. Programa de las Naciones para el Desarrollo (PNUD) y Oficina Nacional de Planificacion. Apartado 1424, Mirador Sur. Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana Ottenwalder, J.A. 1999. Observations on the habitat and ecology of the Hispaniolan Solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus) in the Dominican Republic. Mon. Soc. Hist. Nat. Balears, 6 I Mon. Inst. Est. Bal. 66: 123-168. ISBN: 84- 87026-86-9. Palma de Mallorca. The habitat of the Hispaniolan Solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus) was investiga ted in the Dominican Republic in relation to particular environmental parameters (geomorphology, geologicalstructure, soil type, elevation, life zone, vegetation, rainfall, and temperature). Results are discussed in relation to relevant species environment interactions, particularly habitat preferences and life history patterns of the species. Comparisons on the habitat, ecology and life history are made bet ween S. paradoxus and the Cuban Solenodon (S. cubanus), the only other living member of the genus. Keywords: Solenodon, Caribbean, Antilles, Ecology, Conservation Biology. Observaciones sobre el habitat y ecologia del Solenodon de la Hispaniola (Solenodon paradox us) en la Republica Dominicana. EI habitat del Solenodon de la Hispaniola (Solenodon paradoxus) fue estudiado en la Republica Dominicana en relacion a una serie de parametres ambientales (geomorfologia, estructura geologica, tipo de suelo, elevacion, zona de vida, for macion vegetal, precipitacion, y temperatura). Las relaciones especie-habitat son analizadas usando un modelo empirico descriptivo. Las observaciones sobre inte racciones especie-rnedio ambiente resultantes son discutidas particularmente en relacion a preferencias aparentes de habitat y a los patrones de historia natural de la especie. -

Annual Technical Report Health Reform And

ANNUAL TECHNICAL REPORT October 2002 – September 2003 HEALTH REFORM AND DECENTRALIZATION PROJECT REDSALUD For: Sarah Majerowicz, Cognizant Technical Officer United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mission in the Dominican Republic Contrato USAID #517-C-00-00-00140-00 SO 10: Sustained Improvement in Health of Vulnerable Populations in the Dominican Republic Presented by: Abt Associates Inc. Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Contact: Patricio Murgueytio, Project Director Date: October 2003 Abt Associates Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary..............................................................................................3 Introduction .........................................................................................................5 Social Security and Health Reform Achievements in the Dominican Republic ........... 5 Results Framework............................................................................................. 6 Strategies.......................................................................................................... 9 Principal Technical Achievements .....................................................................10 Local Health Service Management Support Component ..................................12 Grant Administration Activities............................................................................18 Central SESPAS Support Component.................................................................19 HIV/AIDS Sub-component..................................................................................21