Shareholder Activism from a Complexity Theory Lens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intercontinental Hotels Group Plc /New

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 20-F Annual and transition report of foreign private issuers pursuant to sections 13 or 15(d) Filing Date: 2008-03-28 | Period of Report: 2007-12-31 SEC Accession No. 0001156973-08-000368 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER INTERCONTINENTAL HOTELS GROUP PLC /NEW/ Mailing Address Business Address 67 ALMA ROAD 67 ALMA ROAD CIK:858446| IRS No.: 250420260 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0930 WINDSOR WINDSOR Type: 20-F | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-10409 | Film No.: 08717082 BERKSHIRE X0 SL4 3HD BERKSHIRE X0 SL4 3HD SIC: 7011 Hotels & motels 4045513500 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Table of Contents SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 20-F (Mark One) o REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 or þ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2007 or o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 1-10409 InterContinental Hotels Group PLC (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) England and Wales (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 67 Alma Road, Windsor, Berkshire SL4 3HD (Address of principal executive offices) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered American Depositary Shares New York Stock Exchange Ordinary Shares of 1329/47 pence each New York Stock Exchange* * Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission. -

Third Quarter Interim Management Statement Strong Third Quarter Performance

21 October 2014 InterContinental Hotels Group PLC Third Quarter Interim Management Statement Strong third quarter performance Highlights • Global Q3 comparable RevPAR growth of 7.0%; 6.3% in the first nine months • 8k rooms opened in Q3; net system size up 2.7% year on year to 697k rooms • 16k rooms signed in Q3; over 90% of year to date signings located in our priority markets • High quality pipeline of 190k rooms at quarter end; over 45% under construction • Key growth milestones reached for Staybridge Suites and Hotel Indigo; record signings for InterContinental Hotels & Resorts Richard Solomons, Chief Executive of InterContinental Hotels Group PLC, said: “We delivered our best quarterly RevPAR performance in over two years with growth in each of our four regions. Performance in the US was particularly strong where RevPAR was up 8.7%, demonstrating the excellent momentum in the business and the success of our winning strategy. We continue to focus on enhancing our scale position and developing our high quality pipeline, opening 8k rooms in the period, signing 16k rooms into the system, and delivering solid net system size growth of 2.7%. Our preferred brands reached several important milestones in the quarter. Staybridge Suites became the fastest growing brand in its segment to reach 200 open hotels, and Hotel Indigo opened its 60th hotel. InterContinental Hotels and Resorts reinforced its position as the largest global luxury hotel brand with record quarterly signings. Whilst some of our markets face heightened uncertainty and risks, we continue to see strong momentum in the business and remain encouraged by current trading and positive booking trends.” Third Quarter RevPAR performance Americas RevPAR was up 8.4% in the third quarter and 7.5% in the first 9 months. -

Annual Report and Form 20-F 2013 20-F Form and Report Annual Intercontinental Davos, Switzerland

InterContinental Hotels Group PLC Broadwater Park, Denham, Buckinghamshire UB9 5HR United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 1895 512 000 Fax +44 (0) 1895 512 101 Web www.ihgplc.com InterContinental PLC Hotels Group Make a booking at www.ihg.com Annual Report and Form 20 -F 2013 Annual Report and Form 20-F 2013 www.ihgplc.com InterContinental Davos, Switzerland 1777 1946 It all began in 1777 when William Bass opened InterContinental® Hotels & Resorts a brewery in Burton-on-Trent in the UK. In April 1946 Juan Trippe, the founder of Bass made its move into the hotel industry Pan American Airways, had a vision to bring in 1988, buying Holiday Inn International. high-quality hotel accommodation to the By 2003 the business had changed from end of every Pan Am flight route. This led to domestic brewer to international hospitality the first InterContinental being opened in retailer: InterContinental Hotels Group PLC. 1949, the Hotel Grande in Belém, Brazil. From here InterContinental Hotels & Resorts expanded steadily to become the world’s first truly international luxury hospitality brand. The brand’s ethos is to provide insightful, meaningful experiences that enhance our guests’ feeling that they are in a global club. Bass acquired the InterContinental brand in 1998, adding it to our brand portfolio. Front cover Crowne Plaza Resort, Xishuangbanna, 178 hotels; 60,103 rooms open People's Republic of China 51 hotels in the pipeline Contents OVERVIEW STRATEGIC REPORT STRATEGIC GOVERNANCE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FINANCIAL GROUP FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FINANCIAL PARENT -

Group Profit and Loss Account

5 May 2017 InterContinental Hotels Group PLC First Quarter Trading Update Highlights Global Q1 comparable RevPAR1 up 2.7% Enhanced global scale: 7k rooms opened, increasing net system size 3.4% YoY to 767k rooms Building future growth: 14k rooms (112 hotels) signed; pipeline of 232k rooms Richard Solomons, Chief Executive of InterContinental Hotels Group PLC, said: “We have made a good start to 2017, with 3.4% net system size growth year-on-year and 2.7% RevPAR growth driven by increases in both rate and occupancy, and benefitting from the later timing of Easter. We continued our focus on building and leveraging scale in our priority markets, opening 49 hotels in the quarter, including our 300th for Greater China, and signing hotels into our pipeline at the fastest rate for the first quarter since 2008. We also strengthened our boutique portfolio with the opening of a Hotel Indigo property in downtown Los Angeles. Despite the uncertain economic and political environment in some markets, we remain confident in the outlook for 2017 and our ability to deliver sustainable growth into the future.” First Quarter RevPAR performance Group RevPAR was up 2.7%, with rate up 0.8% and occupancy up 1.2% points. The shift in timing of Easter out of Q1 had a positive impact, especially in the Americas and Europe, which we expect to reverse in Q2. Americas RevPAR was up 2.2%, with US RevPAR up 1.9%. Performance stabilised in oil producing markets, where RevPAR was up 1% excluding the favourable impact of Houston hosting the Super Bowl. -

Companies Share Secrets to Success

TOP WORKPLACES REPEAT WINNERS Companies share secrets to success By Valentino Lucio five states. “There’s a buzz around the work- If these companies were sports place that I have never felt before,” teams, they would be considered said one person in the employee dynasties. comments section of the survey. More than a dozen companies “Everyone here knows that we are have been named Top Workplaces part of something amazing and ev- in San Antonio for the fourth year eryone wants to be a part of it.” in a row. The rankings cover small, Beth Rizer has worked at Airros- medium and large companies in in- ti for three years and already has Photos by Tom Reel / San Antonio Express-News dustries from technology to bank- moved up to director of active care Express Lube’s president says the family-run company gives employees ing and health care. The San Anto- and development. Aside from her a sense of community. nio Express-News sponsors the an- new role at work, she also is the nual survey, which began in 2009. singer in the Airrosti band and a Employees at At Airrosti Rehab Centers LLC, player on the company volleyball Express Lube its secret sauce for creating a Top team, which is in first place in its in Schertz Workplace starts with its mission league, she said. work on a and employees, said Kelly Green, “It’s a lot of fun here,” said Rizer, customer’s the company’s CEO. 27. “It’s a little cheesy, but I’m get- car. -

Annual Report 2012

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2012 Statements Financial and Report Annual InterContinental Hotels Group PLC Annual Report and Financial Statements 2012 1 Overview 45 Governance 129 Parent Company 4 Chairman’s Statement 46 The Board of Directors Financial Statements 6 Chief Executive’s Review 48 Executive Committee 130 Parent Company balance sheet 7 Message from the 49 Corporate governance 131 Notes to the Parent Company IHG Owners Association 56 Audit Committee Report Financial Statements 8 Preferred Brands 57 Corporate Responsibility 133 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities Committee Report 134 Independent Auditor’s Report to 9 Business Review 58 Nomination Committee Report the members 10 Industry overview 59 Directors’ Remuneration Report 11 Our strategy 79 Other statutory information 135 Other information 16 Measuring our success 136 Glossary 18 Performance 81 Group Financial Statements 137 Shareholder profiles 20 The Americas 82 Statements of Directors’ 138 Investor information 22 Europe responsibilities 139 Dividend history 24 Asia, Middle East and Africa 83 Independent Auditor’s Report 139 Five year history 26 Greater China to the members 140 Financial calendar 28 Central 84 Group income statement 140 Contacts 28 System Fund 85 Group statement of 141 Forward-looking statements 29 Other financial information comprehensive income 30 Our talented People 86 Group statement 34 Corporate Responsibility of changes in equity 38 Risk management 88 Group statement of financial position 89 Group statement of cash flows 90 Accounting policies 96 Notes to the Group Financial Statements This page Hotel Indigo Xiamen Harbour, China Front cover Holiday Inn London-Stratford City, UK GROuP FInAnCIAL PAREnT COMPAnY OVERVIEW BusInEss review GOVERnAnCE sTATEMEnTs FInAnCIAL sTATEMEnTs OTHER InFORMATIOn 1 About us See pages 14 and 15 for information for andSee 15 pages our on best-in-class 14 Delivery systems this and each way underpins in a responsible business conducting is to committed IHG IHG of trusted the protecting and reputation priorities. -

Intercontinental Hotels Group PLC Half Year Results to 30 June 2013 Good Performance with Strong Signing Activity

InterContinental Hotels Group PLC Half Year Results to 30 June 2013 Good performance with strong signing activity 1 % Change YoY Financial summaryº 2013 2012 Actual CER2 CER & ex. LDs3 Revenue $936m $878m 7% 7% 2% Operating profit $338m $281m 20% 20% 6% Total adjusted EPS 78.2¢ 62.8¢ 25% Total basic EPS4 127.8¢ 93.4¢ 37% Interim dividend per share 23.0¢ 21.0¢ 10% Net debt $861m $564m Richard Solomons, Chief Executive of InterContinental Hotels Group PLC, said: “We have delivered a good performance in the first half, with our preferred brands driving RevPAR growth of 3.7%, including 4.0% in the second quarter. Our global scale has allowed us to reinvest in the business whilst growing margins, resulting in solid underlying profit gains led by our Americas region, and strong cash flows. Consistent with our long track record of returning value to shareholders, we today announce a $350m special dividend. In addition we are increasing the interim dividend by 10% reflecting our good first half results and the confidence we have in the future prospects of the business. We continue to strengthen our foundation for future growth, signing more than 200 hotels into our pipeline, a notable increase on H1 2012 reflecting our owners’ confidence in both IHG and the industry demand drivers. Our high quality pipeline, broad geographic spread and fee based model give us confidence in the outlook, despite the ongoing challenging economic conditions in some of our markets.” Driving Market Share • Total gross revenue5 from hotels in IHG’s system of $10.4bn, up 1% (2% CER). -

Enlarge Image

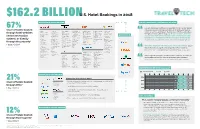

$162.2 BILLIONU.S. Hotel Bookings in 20181 EXAMPLES OF HOTEL BRANDS HOTEL COMPANIES’ COMMENTARY ON OTAS 67% Like any travel agency, OTAs are valuable [in] that they can deliver share of hotels booked infrequent travelers during need times or to hotels and markets • Bulgari • Autograph • Hilton Hotels & • Hilton Garden Inn • InterContinental • Holiday Inn Express • Ascend Hotel where we are less well known. Marriott uses OTAs less often than through hotel websites, • The Ritz-Carlton Collection Hotels Resorts • Hampton by Hilton Hotels & Resorts Hotels Collection • The Ritz-Carlton • Tribute Portfolio • Waldorf Astoria • Tru by Hilton • Kimpton Hotels & • Holiday Inn Resort • Cambria Hotels & the typical industry hotel company. IN FACT IN 2016, OTA HAS Reserve • Design Hotels Hotels & Resorts Restaurants • Holiday Inn Club Suites METASEARCH “ • Homewood Suites ACCOUNTED FOR APPROXIMATELY 10% OF MARRIOTT AND central reservation • St. Regis • Gaylord Hotels • Conrad Hotels & by Hilton • HUALUXE Hotels Vacations • Comfort Inn Resorts and Resorts • W • Courtyard • Home2 Suites by • Staybridge Suites • Comfort Suites STARWOOD COMBINED ROOM NIGHTS SOLD WORLDWIDE. • Canopy by Hilton, • Crowne Plaza Hotels systems, or directly • EDITION • Four Points by Hilton • Candlewood Suites • Sleep Inn • Curio — A Collection & Resorts Stephanie Linnartz, EVP & Global Chief Commercial Officer, Marriott International (03.21.2017) • JW Marriott Sheraton • Hilton Grand • Regent • Vacation Rentals by 1 by Hilton Vacations • Hotel Indigo Choice Hotels • The Luxury • SpringHill Suites • Voco through the property • Tapestry Collection • EVEN Hotels Collection • Fairfield Inn & Suites • LXR Hotels & • Avid • Quality by Hilton Resorts • Holiday Inn Hotels • Marriott Hotels • Residence Inn • Clarion (~$108.7 billion) • DoubleTree by Hilton • Motto • Westin • TownePlace Suites • MainStay Suites THE OTAS ARE PLUS OR MINUS 10% OF OUR BUSINESS. -

ANNUAL REPORT and FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2005 Financial Highlights

ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2005 financial highlights Transformation to a managed and franchised business nearing completion. InterContinental Hotels Group now delivers more stable earnings and has a clear growth focus. Continuing operating profit* up 42% from £134m to £190m with operating profit margin up 4 percentage points. Group operating profit £317m, up £20m. Adjusted† earnings per share from continuing business up 44% from 17.3p to 24.9p. Group basic earnings per share up 77% from 53.9p to 95.2p driven by gain on disposal of operations. Final dividend up 7% from 10.00p to 10.70p per share: total 2005 dividend up 7% from 14.30p§ to 15.30p per share. 9.0% RevPAR# growth across the Group’s 3,600 hotels, mostly rate driven with strongest trading in the Americas. 70,000 rooms signed in 2005, up 57% over 2004. Our contract pipeline is the industry’s largest at 108,500 rooms, 20% of existing room count. Room count up 3,300 to 537,500 rooms. £500m special interim dividend to be paid during the second quarter of 2006. * Excludes Britvic and hotel assets sold or held for sale at 31 December 2005; operating profit before other operating income and expenses. † Excludes special items and gain on disposal of assets, net of related tax. § Excludes special interim dividend paid in December 2004. # Room revenue divided by the number of room nights available. 1 OPERATING AND FINANCIAL REVIEW 76 US GAAP INFORMATION 18 DIRECTORS’ REPORT 80 DIRECTORS’ RESPONSIBILITIES IN RELATION 20 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE TO THE GROUP FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 24 -

Group Profit and Loss Account

5 May 2017 InterContinental Hotels Group PLC First Quarter Trading Update Highlights Global Q1 comparable RevPAR1 up 2.7% Enhanced global scale: 7k rooms opened, increasing net system size 3.4% YoY to 767k rooms Building future growth: 14k rooms (112 hotels) signed; pipeline of 232k rooms Richard Solomons, Chief Executive of InterContinental Hotels Group PLC, said: “We have made a good start to 2017, with 3.4% net system size growth year-on-year and 2.7% RevPAR growth driven by increases in both rate and occupancy, and benefitting from the later timing of Easter. We continued our focus on building and leveraging scale in our priority markets, opening 49 hotels in the quarter, including our 300th for Greater China, and signing hotels into our pipeline at the fastest rate for the first quarter since 2008. We also strengthened our boutique portfolio with the opening of a Hotel Indigo property in downtown Los Angeles. Despite the uncertain economic and political environment in some markets, we remain confident in the outlook for 2017 and our ability to deliver sustainable growth into the future.” First Quarter RevPAR performance Group RevPAR was up 2.7%, with rate up 0.8% and occupancy up 1.2% points. The shift in timing of Easter out of Q1 had a positive impact, especially in the Americas and Europe, which we expect to reverse in Q2. Americas RevPAR was up 2.2%, with US RevPAR up 1.9%. Performance stabilised in oil producing markets, where RevPAR was up 1% excluding the favourable impact of Houston hosting the Super Bowl. -

Annual Report and Form 20-F 2014 20-F Form and Report Annual

InterContinental Hotels Group PLC Broadwater Park, Denham, Buckinghamshire UB9 5HR United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 1895 512 000 Fax +44 (0) 1895 512 101 InterContinental PLC Hotels Group Web www.ihgplc.com Make a booking at www.ihg.com Annual Report and Form 20-F 2014 Annual Report and Form 20-F 2014 www.ihgplc.com Contents Strategic Report Strategic Report The Strategic Report on pages 2 to 51 2 IHG at a glance was approved by the Board on 4 Our preferred brands 16 February 2015 6 Chairman’s statement George Turner, Company Secretary 8 Chief Executive Offi cer’s review 10 Industry overview 12 Our business model 14 Our strategy for high-quality growth 16 Winning Model 18 Targeted Portfolio 20 Our Winning Model and Targeted Portfolio in action 22 Disciplined Execution 24 Doing business responsibly 26 Risk management 30 Key performance indicators 34 Performance Governance 54 Chairman’s overview 55 Corporate Governance 57 Who is on our Board of Directors 60 Who is on our Executive Committee 65 Audit Committee Report 68 Corporate Responsibility Committee Report 69 Nomination Committee Report 70 Statement of compliance with the UK Corporate Governance Code 72 Directors’ Report 76 Directors’ Remuneration Report Group Financial Statements 94 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 95 Independent Auditor’s UK Report 99 Independent Auditor’s US Report 100 Group Financial Statements 107 Accounting policies Dream 114 Notes to the Group Financial Statements Parent Company Financial Statements 156 Parent company balance sheet 157 Notes to the Parent Company Financial Statements Additional Information 162 Group information 171 Shareholder information 179 Useful information 181 Exhibits ‘Guest Journey’ – Step One 182 Form 20-F cross-reference guide The Dream phase of the ‘Guest Journey’ 184 Glossary is one of the most exciting parts of travel 186 Forward-looking statements for many of our guests as they research, seek inspiration, and dream, about their future trip. -

Intercontinental Hotels Group PLC First Quarter Interim Management Statement Solid Trading and Progress on Asset Sales

8 May 2013 InterContinental Hotels Group PLC First Quarter Interim Management Statement Solid trading and progress on asset sales Highlights • Global Q1 RevPAR growth of 3.1%, driven by 2.0% average daily rate growth. • System size up 1.9% year on year to 674k rooms as at 31 March. • 14k rooms signed in Q1, taking the pipeline to 176k rooms at the quarter end. • Loyalty scheme renamed as IHG Rewards Club, which will offer enhanced benefits including free internet for all members, an industry first. • InterContinental London Park Lane disposal completed for $469m gross cash proceeds, with management contract secured for up to 60 years. Richard Solomons, Chief Executive of InterContinental Hotels Group PLC, said: “We have had an encouraging start to our 10 th anniversary year, with solid trading performance in the first quarter driven predominantly by growth in rate. Our preferred brands and global scale helped deliver good pipeline growth in the quarter, with over 100 hotels signed, led by our Americas and Greater China regions. The disposal of InterContinental London Park Lane, which completed on 1 May, highlights the value of our asset portfolio and the attractiveness of InterContinental as one of the world’s leading luxury hotel brands. It is also another step in our long standing commitment to reduce the capital intensity of IHG. Our high quality pipeline, broad geographic spread and fee based model give us confidence for the year ahead, despite the ongoing challenging economic conditions in several of our markets." RevPAR performance Group Q1 global RevPAR growth of 3.1%, with rate up 2.0% and occupancy up 0.6%pts.