Ought a Four-Dimensionalist to Believe in Temporal Parts?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parts of Persons Identity and Persistence in a Perdurantist World

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO Doctoral School in Philosophy and Human Sciences (XXXI Cycle) Department of Philosophy “Piero Martinetti” Parts of Persons Identity and persistence in a perdurantist world Ph.D. Candidate Valerio BUONOMO Tutors Prof. Giuliano TORRENGO Prof. Paolo VALORE Coordinator of the Doctoral School Prof. Marcello D’AGOSTINO Academic year 2017-2018 1 Content CONTENT ........................................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1. PERSONAL IDENTITY AND PERSISTENCE...................................................................... 8 1.1. The persistence of persons and the criteria of identity over time .................................. 8 1.2. The accounts of personal persistence: a standard classification ................................... 14 1.2.1. Mentalist accounts of personal persistence ............................................................................ 15 1.2.2. Somatic accounts of personal persistence .............................................................................. 15 1.2.3. Anti-criterialist accounts of personal persistence ................................................................... 16 1.3. The metaphysics of persistence: the mereological account ......................................... -

INTUITION .THE PHILOSOPHY of HENRI BERGSON By

THE RHYTHM OF PHILOSOPHY: INTUITION ·ANI? PHILOSO~IDC METHOD IN .THE PHILOSOPHY OF HENRI BERGSON By CAROLE TABOR FlSHER Bachelor Of Arts Taylor University Upland, Indiana .. 1983 Submitted ~o the Faculty of the Graduate College of the · Oklahoma State University in partial fulfi11ment of the requirements for . the Degree of . Master of Arts May, 1990 Oklahoma State. Univ. Library THE RHY1HM OF PlllLOSOPHY: INTUITION ' AND PfnLoSOPlllC METHOD IN .THE PHILOSOPHY OF HENRI BERGSON Thesis Approved: vt4;;. e ·~lu .. ·~ests AdVIsor /l4.t--OZ. ·~ ,£__ '', 13~6350' ii · ,. PREFACE The writing of this thesis has bee~ a tiring, enjoyable, :Qustrating and challenging experience. M.,Bergson has introduced me to ·a whole new way of doing . philosophy which has put vitality into the process. I have caught a Bergson bug. His vision of a collaboration of philosophers using his intuitional m~thod to correct, each others' work and patiently compile a body of philosophic know: ledge is inspiring. I hope I have done him justice in my description of that vision. If I have succeeded and that vision catches your imagination I hope you Will make the effort to apply it. Please let me know of your effort, your successes and your failures. With the current challenges to rationalist epistemology, I believe the time has come to give Bergson's method a try. My discovery of Bergson is. the culmination of a development of my thought, one that started long before I began my work at Oklahoma State. However, there are some people there who deserv~. special thanks for awakening me from my ' "''' analytic slumber. -

Duration, Temporality and Self

Duration, Temporality and Self: Prospects for the Future of Bergsonism by Elena Fell A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire 2007 2 Student Declaration Concurrent registration for two or more academic awards I declare that white registered as a candidate for the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. Material submitted for another award I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work Signature of Candidate Type of Award Doctor of Philosophy Department Centre for Professional Ethics Abstract In philosophy time is one of the most difficult subjects because, notoriously, it eludes rationalization. However, Bergson succeeds in presenting time effectively as reality that exists in its own right. Time in Bergson is almost accessible, almost palpable in a discourse which overcomes certain difficulties of language and traditional thought. Bergson equates time with duration, a genuine temporal succession of phenomena defined by their position in that succession, and asserts that time is a quality belonging to the nature of all things rather than a relation between supposedly static elements. But Rergson's theory of duration is not organised, nor is it complete - fragments of it are embedded in discussions of various aspects of psychology, evolution, matter, and movement. My first task is therefore to extract the theory of duration from Bergson's major texts in Chapters 2-4. -

The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: the Possibility of Time Travel

University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well Honors Capstone Projects Student Scholarship 2017 The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: The Possibility of Time Travel Ramitha Rupasinghe University of Minnesota, Morris, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/honors Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Rupasinghe, Ramitha, "The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: The Possibility of Time Travel" (2017). Honors Capstone Projects. 1. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/honors/1 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: The possibility of time travel Ramitha Rupasinghe IS 4994H - Honors Capstone Project Defense Panel – Pieranna Garavaso, Michael Korth, James Togeas University of Minnesota, Morris Spring 2017 1. Introduction Time is mysterious. Philosophers and scientists have pondered the question of what time might be for centuries and yet till this day, we don’t know what it is. Everyone talks about time, in fact, it’s the most common noun per the Oxford Dictionary. It’s in everything from history to music to culture. Despite time’s mysterious nature there are a lot of things that we can discuss in a logical manner. Time travel on the other hand is even more mysterious. -

Bergsoniana, 1

Bergsoniana 1 | 2021 Reassessing Bergson Bergsonian Answers to Contemporary Persistence Questions Florian Fischer Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/bergsoniana/448 DOI: 10.4000/bergsoniana.448 ISSN: 2800-874X Publisher Société des amis de Bergson Electronic reference Florian Fischer, “Bergsonian Answers to Contemporary Persistence Questions”, Bergsoniana [Online], 1 | 2021, Online since 01 July 2021, connection on 14 September 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/bergsoniana/448 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/bergsoniana.448 Les contenus de la revue sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. BERGSONIAN ANSWERS TO CONTEMPORARY PERSISTENCE QUESTIONS Florian FISCHER Introduction Time is one of the central topics of contemporary analytic philosophy, and Henri Bergson is one of the most important philosophers of time, but still Bergson plays virtually no role in the contemporary analytic debate about time. In contrast to his poor reception,1 Henri Bergson has a lot to offer analytic philosophy, as I will argue. More precisely, I will illustrate what the debates about persistence and ontology of time might gain from incorporating Bergsonian ideas. To do so, I will first investigate persistence, i.e., existence through time. The focal point of the contemporary analytic debate is how to conceptualise change without letting the involved incompatibilities lead to a logical contradiction. This can be called a horizontal way of posing the question, namely, how to reconcile two incompatible properties had by one entity at two points in time. Bergson famously asserted that objects are ontologically secondary, mind- dependent abstractions from an underlying dynamic reality. -

Four-Dimensionalism, Eternalism, and Deprivationist Accounts of the Evil of Death

Synthese https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03393-0 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Four-dimensionalism, eternalism, and deprivationist accounts of the evil of death Andrew Brenner1 Received: 22 June 2021 / Accepted: 28 August 2021 © The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature B.V. 2021 Abstract Four-dimensionalists think that we persist over time by having different temporal parts at each of the times at which we exist. Eternalists think that all times are equally real. Deprivationists think that death is an evil for the one who dies because it deprives them of something. I argue that four-dimensionalist eternalism, conjoined with a standard deprivationist account of the evil of death, has surprising implications for what we should think about the evil of death. In particular, given these assumptions, we will lack any grounds for thinking that death is an evil for some individuals for whom we would antecedently expect it to be an evil, namely those individuals who cease to exist at death. Alternatively, we will only have some grounds for thinking that death is an evil for certain individuals for whom we might antecedently be more inclined to think death is not an evil, namely those individuals who survive death, in the sense that they continue to exist after death. Keywords Death · Evil of death · Four-dimensionalism · Eternalism · Perdurantism · Stage theory 1 Introduction According to four-dimensionalism, things which persist over time do so by hav- ing temporal parts at each of the times at which they exist. Four-dimensionalism is almost always conjoined with an eternalist temporal ontology, according to which past, present, and future things are equally real. -

Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting

European Medicines Agency June 1995 CPMP/ICH/377/95 ICH Topic E 2 A Clinical Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting Step 5 NOTE FOR GUIDANCE ON CLINICAL SAFETY DATA MANAGEMENT: DEFINITIONS AND STANDARDS FOR EXPEDITED REPORTING (CPMP/ICH/377/95) APPROVAL BY CPMP November 1994 DATE FOR COMING INTO OPERATION June 1995 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 85 75 Fax (44-20) 75 23 70 40 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.eu.int EMEA 2006 Reproduction and/or distribution of this document is authorised for non commercial purposes only provided the EMEA is acknowledged CLINICAL SAFETY DATA MANAGEMENT: DEFINITIONS AND STANDARDS FOR EXPEDITED REPORTING ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline 1. INTRODUCTION It is important to harmonise the way to gather and, if necessary, to take action on important clinical safety information arising during clinical development. Thus, agreed definitions and terminology, as well as procedures, will ensure uniform Good Clinical Practice standards in this area. The initiatives already undertaken for marketed medicines through the CIOMS-1 and CIOMS-2 Working Groups on expedited (alert) reports and periodic safety update reporting, respectively, are important precedents and models. However, there are special circumstances involving medicinal products under development, especially in the early stages and before any marketing experience is available. Conversely, it must be recognised that a medicinal product will be under various stages of development and/or marketing in different countries, and safety data from marketing experience will ordinarily be of interest to regulators in countries where the medicinal product is still under investigational-only (Phase 1, 2, or 3) status. -

Travelling in Time: How to Wholly Exist in Two Places at the Same Time

Travelling in Time: How to Wholly Exist in Two Places at the Same Time 1 Introduction It is possible to wholly exist at multiple spatial locations at the same time. At least, if time travel is possible and objects endure, then such must be the case. To accommodate this possibility requires the introduction of a spatial analog of either relativising properties to times—relativising properties to spatial locations—or of relativising the manner of instantiation to times—relativising the manner of instantiation to spatial locations. It has been suggested, however, that introducing irreducibly spatially relativised or spatially adverbialised properties presents some difficulties for the endurantist. I will consider an objection according to which embracing such spatially relativised properties could lead us to reject mereology altogether in favour of a metaphysics according to which objects are wholly present at every space-time point at which they exist. I argue that although such a view is coherent, there are some good reasons to reject it. Moreover, I argue that the endurantist can introduce spatially relativised or adverbialised properties without conceding that objects lack spatial parts. Such a strategy has the additional advantage that it allows the endurantist not only to explain time travel, but also to reconcile our competing intuitions about cases of fission. The possibility of travelling back in time to a period in which one’s earlier self or one’s ancestors exist, raises a number of well-worn problems (Grey, 1999; Chambers, 1999; Horwich, 1975 and Sider, 2002). In this paper I am concerned with only one of these: how is it that an object can travel back in time to meet its earlier self, thus existing at two different spatial locations at one and the same time? Four-dimensionalists have an easy answer to this question. -

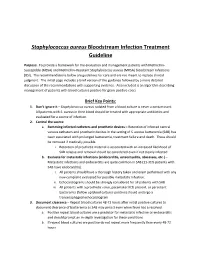

Staphylococcus Aureus Bloodstream Infection Treatment Guideline

Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infection Treatment Guideline Purpose: To provide a framework for the evaluation and management patients with Methicillin- Susceptible (MSSA) and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections (BSI). The recommendations below are guidelines for care and are not meant to replace clinical judgment. The initial page includes a brief version of the guidance followed by a more detailed discussion of the recommendations with supporting evidence. Also included is an algorithm describing management of patients with blood cultures positive for gram-positive cocci. Brief Key Points: 1. Don’t ignore it – Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a blood culture is never a contaminant. All patients with S. aureus in their blood should be treated with appropriate antibiotics and evaluated for a source of infection. 2. Control the source a. Removing infected catheters and prosthetic devices – Retention of infected central venous catheters and prosthetic devices in the setting of S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) has been associated with prolonged bacteremia, treatment failure and death. These should be removed if medically possible. i. Retention of prosthetic material is associated with an increased likelihood of SAB relapse and removal should be considered even if not clearly infected b. Evaluate for metastatic infections (endocarditis, osteomyelitis, abscesses, etc.) – Metastatic infections and endocarditis are quite common in SAB (11-31% patients with SAB have endocarditis). i. All patients should have a thorough history taken and exam performed with any new complaint evaluated for possible metastatic infection. ii. Echocardiograms should be strongly considered for all patients with SAB iii. All patients with a prosthetic valve, pacemaker/ICD present, or persistent bacteremia (follow up blood cultures positive) should undergo a transesophageal echocardiogram 3. -

Presentism/Eternalism and Endurantism/Perdurantism: Why the Unsubstantiality of the First Debate Implies That of the Second1

1 Presentism/Eternalism and Endurantism/Perdurantism: why the 1 unsubstantiality of the first debate implies that of the second Forthcoming in Philosophia Naturalis Mauro Dorato (Ph.D) Department of Philosophy University of Rome Three [email protected] tel. +393396070133 http://host.uniroma3.it/dipartimenti/filosofia/personale/doratoweb.htm Abstract The main claim that I want to defend in this paper is that the there are logical equivalences between eternalism and perdurantism on the one hand and presentism and endurantism on the other. By “logical equivalence” I mean that one position is entailed and entails the other. As a consequence of this equivalence, it becomes important to inquire into the question whether the dispute between endurantists and perdurantists is authentic, given that Savitt (2006) Dolev (2006) and Dorato (2006) have cast doubts on the fact that the debate between presentism and eternalism is about “what there is”. In this respect, I will conclude that also the debate about persistence in time has no ontological consequences, in the sense that there is no real ontological disagreement between the two allegedly opposite positions: as in the case of the presentism/eternalism debate, one can be both a perdurantist and an endurantist, depending on which linguistic framework is preferred. The main claim that I want to defend in this paper is that the there are logical equivalences between eternalism and perdurantism on the one hand and presentism and endurantism on the other. By “logical equivalence” I mean that one position is entailed and entails the other. As a consequence of this equivalence, it becomes important to inquire into the question whether the dispute between endurantists and perdurantists is authentic, given that Savitt (2006) Dolev (2006) and Dorato (2006) have cast doubts on the fact that the debate between presentism and eternalism is about “what there is”. -

The Relationship of Drought Frequency and Duration to Time Scales

Eighth Conference on Applied Climatology, 17-22 January 1993, Anaheim, California if ~ THE RELATIONSHIP OF DROUGHT FREQUENCY AND DURATION TO TIME SCALES Thomas B. McKee, Nolan J. Doesken and John Kleist Department of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 1.0 INTRODUCTION Five practical issues become important in any analysis of drought. These include: 1) time scale, 2) The definition of drought has continually been probability, 3) precipitation deficit, 4) application of the a stumbling block for drought monitoring and analysis. definition to precipitation and to the five water supply Wilhite and Glantz (1985) completed a thorough review variables, and 5) the relationship of the definition to the of dozens of drought definitions and identified six impacts of drought. Frequency, duration and intensity overall categories: meteorological, climatological, of drought all become functions that depend on the atmospheric, agricultural, hydrologic and water implicitly or explicitly established time scales. Our management. Dracup et al. (1980) also reviewed experience in providing drought information to a definitions. All points of view seem to agree that collection of decision makers in Colorado is that they drought is a condition of insufficient moisture caused have a need for current conditions expressed in terms by a deficit in precipitation over some time period. of probability, water deficit, and water supply as a Difficulties are primarily related to the time period over percent of average using recent climatic history (the which deficits accumulate and to the connection of the last 30 to 100 years) as the basis for comparison. No deficit in precipitation to deficits in usable water single drought definition or analysis method has sources and the impacts that ensue. -

Unity of Mind, Temporal Awareness, and Personal Identity

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE THE LEGACY OF HUMEANISM: UNITY OF MIND, TEMPORAL AWARENESS, AND PERSONAL IDENTITY DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Philosophy by Daniel R. Siakel Dissertation Committee: Professor David Woodruff Smith, Chair Professor Sven Bernecker Associate Professor Marcello Oreste Fiocco Associate Professor Clinton Tolley 2016 © 2016 Daniel R. Siakel DEDICATION To My mother, Anna My father, Jim Life’s original, enduring constellation. And My “doctor father,” David Who sees. “We think that we can prove ourselves to ourselves. The truth is that we cannot say that we are one entity, one existence. Our individuality is really a heap or pile of experiences. We are made out of experiences of achievement, disappointment, hope, fear, and millions and billions and trillions of other things. All these little fragments put together are what we call our self and our life. Our pride of self-existence or sense of being is by no means one entity. It is a heap, a pile of stuff. It has some similarities to a pile of garbage.” “It’s not that everything is one. Everything is zero.” Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche “Galaxies of Stars, Grains of Sand” “Rhinoceros and Parrot” ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER I: Hume’s Appendix Problem and Associative Connections in the Treatise and Enquiry §1. General Introduction to Hume’s Science of Human Nature 6 §2. Introducing Hume’s Appendix Problem 8 §3. Contextualizing Hume’s Appendix Problem 15 §4.