American Music Review the H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miley Cyrus Debuts at #1 on the Top Rock Albums Chart with Plastic Hearts Get It Here

MILEY CYRUS DEBUTS AT #1 ON THE TOP ROCK ALBUMS CHART WITH PLASTIC HEARTS GET IT HERE December 7, 2020 - Artist and trailblazer Miley Cyrus’ critically acclaimed seventh studio album, Plastic Hearts has debuted at #1 on Billboard’s Top Rock Albums chart, her first number 1 on this chart, and 6th number 1 album. The album also debuted at number 2 on the Billboard 200, giving Miley the most top 10 album debuts on the chart for female artists this century. The album has debuted in the Top 10 in more than 10 countries. Tracks on Plastic Hearts have been streamed cumulatively over 750 million times worldwide. Plastic Hearts is out now via RCA Records - listen here Her raw and raucous album has earned high praise: “Maybe rock’s not dead — it’s just in the capable hands of Miley Cyrus.”-The New York Times “Miley Cyrus’ Glam Throwback ‘Plastic Hearts’ Is Her Most Self-Assured Record Yet.”-Rolling Stone “Cyrus’ glam-rock pivot draws upon her decade of delivering whip-smart lyrics and enormous hooks to arrive fully formed and often spectacular.”-Billboard “Reflecting on her worst times from the distance that maturity allows, Miley Cyrus has come through with her best album.”-Vulture “The message is clear: Miley Cyrus rocks.”-Stereogum “What Miley does with her voice throughout the album is really its main attraction.”-Nylon “Plastic Hearts, Cyrus’s incendiary new record, punctuates the 28-year-old singer’s greatest sonic reinvention yet — a retro-charged tribute to no-nonsense frontwomen: Debbie Harry and Heart’s Ann Wilson, Stevie Nicks and Joan Jett.”-SPIN “Miley Cyrus Is Perfect for the Rock-and-Roll Revival.”-The Atlantic Miley will be performing her hit single, “Prisoner,” on Jimmy Kimmel Live! on December 7th. -

Artistbio 957.Pdf

An undiscovered island. An epic journey. An illustrious ship. Known just by its name and its logo, GALANTIS could be all or none of these things. A Google search only turns up empty websites and social pages, and mention of a one-off A-Trak collaboration. Is it beats? Art? Something else entirely? At the most basic level, GALANTIS is two friends making music together. The fact that they’re Christian “Bloodshy” Karlsson of Miike Snow and Linus Eklow, aka Style of Eye, is what changes the plot. The accomplished duo’s groundbreaking work as GALANTIS destroys current electronic dance music tropes, demonstrating that emotion and musicianship can indeed coexist with what Eklow calls “a really really big kind of vibe.” “GALANTIS is about challenging, not following.” says Karlsson. Karlsson should know about shaking things up. As half of production duo Bloodshy & Avant, he reinvented pop divas like Madonna, Britney Spears and Kylie Minogue in the early 2000s. He co-wrote and produced Spears’ stunning, career-changing single “Toxic” to the tune of a 2005 Grammy Award for Best Dance Recording. Since then he’s been breaking more ground as one-third of mysterious, jackalobe-branded band Miike Snow. The trio’s two albums, 2009’s self-titled debut and 2011’s Happy To You, fuse the warm pulse of dance music with inspired songcraft, spanning rock, indie, pop and soul. And they recreated that special synthesis live, playing over 300 shows, including big stages like Coachella, Lollapalooza and Ultra Music Festival. As Style of Eye, Eklow has cut his own path through the wilds of electronic music for the last decade, defying genre and releasing work on a diverse swath of labels including of- the-moment EDM purveyors like Fool’s Gold, OWSLA and Refune; and underground stalwarts like Classic, Dirtybird and Pickadoll. -

The Best Totally-Not-Planned 'Shockers'

Style Blog The best totally-not-planned ‘shockers’ in the history of the VMAs By Lavanya Ramanathan August 30 If you have watched a music video in the past decade, you probably did not watch it on MTV, a network now mostly stuck in a never-ending loop of episodes of “Teen Mom.” This fact does not stop MTV from continuing to hold the annual Video Music Awards, and it does not stop us from tuning in. Whereas this year’s Grammys were kind of depressing, we can count on the VMAs to be a slightly morally objectionable mess of good theater. (MTV has been boasting that it has pretty much handed over the keys to Miley Cyrus, this year’s host, after all.) [VMAs 2015 FAQ: Where to watch the show, who’s performing, red carpet details] Whether it’s “real” or not doesn’t matter. Each year, the VMAs deliver exactly one ugly, cringe-worthy and sometimes actually surprising event that imprints itself in our brains, never to be forgotten. Before Sunday’s show — and before Nicki Minaj probably delivers this year’s teachable moment — here are just a few of those memorable VMA shockers. 1984: Madonna sings about virginity in front of a blacktie audience It was the first VMAs, Bette Midler (who?) was co-hosting and the audience back then was a sea of tux-wearing stiffs. This is all-important scene-setting for a groundbreaking performance by young Madonna, who appeared on the top of an oversize wedding cake in what can only be described as head-to-toe Frederick’s of Hollywood. -

From Disney to Disaster: the Disney Corporation’S Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks

From Disney to Disaster: The Disney Corporation’s Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks BY Kelsey N. Reese Spring 2021 WMNST 492W: Senior Capstone Seminar Dr. Jill Wood Reese 2 INTRODUCTION The popularized phrase “celebrity trainwreck” has taken off in the last ten years, and the phrase actively evokes specified images (Doyle, 2017). These images usually depict young women hounded by paparazzi cameras that are most likely drunk or high and half naked after a wild night of partying (Doyle, 2017). These girls then become the emblem of celebrity, bad girl femininity (Doyle, 2017; Kiefer, 2016). The trainwreck is always a woman and is usually subject to extra attention in the limelight (Doyle, 2017). Trainwrecks are in demand; almost everything they do becomes front page news, especially if their actions are seen as scandalous, defamatory, or insane. The exponential growth of the internet in the early 2000s created new avenues of interest in celebrity life, including that of social media, gossip blogs, online tabloids, and collections of paparazzi snapshots (Hamad & Taylor, 2015; Mercer, 2013). What resulted was 24/7 media access into the trainwreck’s life and their long line of outrageous, commiserable actions (Doyle, 2017). Kristy Fairclough coined the term trainwreck in 2008 as a way to describe young, wild female celebrities who exemplify the ‘good girl gone bad’ image (Fairclough, 2008; Goodin-Smith, 2014). While the coining of the term is rather recent, the trainwreck image itself is not; in their book titled Trainwreck, Jude Ellison Doyle postulates that the trainwreck classification dates back to feminism’s first wave with Mary Wollstonecraft (Anand, 2018; Doyle, 2017). -

Avid Congratulates Its Many Customers Nominated for the 57Th Annual GRAMMY(R) Awards

December 10, 2014 Avid Congratulates Its Many Customers Nominated for the 57th Annual GRAMMY(R) Awards Award Nominees Created With the Company's Industry-Leading Music Solutions Include Beyonce's Beyonce, Ed Sheeran's X, and Pharrell Williams' Girl BURLINGTON, Mass., Dec. 10, 2014 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Avid® (Nasdaq:AVID) today congratulated its many customers recognized as award nominees for the 57th Annual GRAMMY® Awards for their outstanding achievements in the recording arts. The world's most prestigious ceremony for music excellence will honor numerous artists, producers and engineers who have embraced Avid EverywhereTM, using the Avid MediaCentral Platform and Avid Artist Suite creative tools for music production. The ceremony will take place on February 8, 2015 at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, California. Avid audio professionals created Record of the Year and Song of the Year nominees Stay With Me (Darkchild Version) by Sam Smith, Shake It Off by Taylor Swift, and All About That Bass by Meghan Trainor; and Album of the Year nominees Morning Phase by Beck, Beyoncé by Beyoncé, X by Ed Sheeran, In The Lonely Hour by Sam Smith, and Girl by Pharrell Williams. Producer Noah "40" Shebib scored three nominations: Album of the Year and Best Urban Contemporary Album for Beyoncé by Beyoncé, and Best Rap Song for 0 To 100 / The Catch Up by Drake. "This is my first nod for Album Of The Year, and I'm really proud to be among such elite company," he said. "I collaborated with Beyoncé at Jungle City Studios where we created her track Mine using their S5 Fusion. -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

Sports Eye Protection for Men, Women & Youth

2017 ® Our vision is protecting yours. Sports Eye Protection for Men, Women & Youth ® BANGERZ® SPORTZ, A DIVISION OF HALO Sports®, IS A RECOGNIZED LEADER IN THE natIONAL MOVEMENT to EDUCate AND PROMOTE THE AWARENESS OF EYE SAFETY FOR SCHOLASTIC, RECreatIONAL, AND EXTREME sports. BANGERZ® SPORTZ ENGINEERS PRODUCTS to HELP PROTECT THE EYE FROM THE IMpaCT OF A BALL OR OTHER sport GEAR, AS WELL AS AN OPPONENT’S HANDS OR ELBOWS that POSE A threat to AN athLETE’S VISUAL SAFETY. WE OFFER A COMPLETE SELECTION OF sport SPECIFIC EYEGUARDS AND HIGH IMpaCT EYEWEAR WITH shatter RESIstant NON-PRESCRIPTION LENSES FOR ACTIVE PEOPLE OF ALL AGES. FOR OVER 30 YEARS HALO Sports® HAS EARNED ITS LEGENDARY REPUtatION FOR CRAFTING CertIFIED PROTECTIVE EYEWEAR. OUR RECS SPECS® BRAND IS THE NUMBER ONE SELLING COLLECTION OF ASTM APPROVED PRESCRIP- TION sport GOGGLES IN THE WORLD BANGERZ® SPORTZ... OUR VISION IS PROTECTING YOURS WHY WEAR BANGERZ SPORTZ EYE PROTECTION? HERE ARE THE FACTS • AN ESTIMateD 2.4 MILLION EYE INJURIES OCCUR IN THE US EACH YEAR • MORE THAN 600,000 ARE DOCUMENTED EYE INJURIES RELateD to sports AND RECreatION • 42,000 OF THESE INJURIES ARE OF A SEVERITY that REQUIRES EMERGENCY ROOM attentION • IT IS ESTIMATED that EACH YEAR 13,500 LEGALLY BLINDING sports EYE INJURIES OCCUR • NEARLY 1 MILLION AMERICANS HAVE LOST SOME DEGREE OF SIGHT DUE to EYE INJURY • EYE INJURY IS THE LEADING CAUSE OF MONOCULAR BLINDNESS • Sports PartICIpants USING EYEWEAR OR SUNWEAR that DOES NOT CONFORM to ASTM PROTECTION stanDARDS ARE at A FAR MORE SEVERE RISK OF EYE INJURY THAN partICIpants USING NO EYE PROTECTION at ALL. -

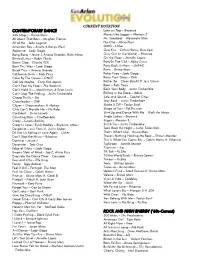

Front of House Master Song List

CURRENT ROTATION CONTEMPORARY DANCE Love on Top – Beyoncé 24K Magic – Bruno Mars Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Mr. Saxobeat – Alexandra Stan All of Me – John Legend No One – Alicia Keys American Boy – Estelle & Kanye West OMG – Usher Applause – Lady Gaga One Kiss – Calvin Harris, Dua Lipa Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj Only Girl (in the World) – Rihanna Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke On the Floor – Jennifer Lopez Boom Clap – Charlie XCX Party In The USA – Miley Cyrus Born This Way – Lady Gaga Party Rock Anthem – LMFAO Break Free – Ariana Grande Perm – Bruno Mars California Gurls – Katy Perry Poker Face – Lady Gaga Cake By The Ocean – DNCE Raise Your Glass – Pink Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae Jepsen Rather Be – Clean Bandit ft. Jess Glynn Can’t Feel My Face – The Weeknd Roar – Katy Perry Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Rock Your Body – Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Rolling in the Deep – Adele Cheap Thrills – Sia Safe and Sound – Capital Cities Cheerleader – OMI Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake Closer – Chainsmokers ft. Halsey Shake It Off – Taylor Swift Club Can’t Handle Me – Flo Rida Shape of You – Ed Sheeran Confident – Demi Lovato Shut Up and Dance With Me – Walk the Moon Counting Stars – OneRepublic Single Ladies – Beyoncé Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Sugar – Maroon 5 Crazy In Love / Funk Medley – Beyoncé, others Suit & Tie – Justin Timberlake Despacito – Luis Fonsi ft. Justin Bieber Take Back the Night – Justin Timberlake DJ Got Us Falling in Love Again – Usher That’s What I Like – Bruno Mars Don’t Stop the Music – Rihanna There’s Nothing Holding Me Back – Shawn Mendez Domino – Jessie J This Is What You Came For – Calvin Harris ft. -

Khalid Teenage Dream Album Download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Passenger – Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) ZIP

khalid teenage dream album download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Passenger – Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) ZIP. DOWNLOAD Passenger Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) ZIP & MP3 File. Ever Trending Star drops this amazing song titled “Passenger – Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) Album“, its available for your listening pleasure and free download to your mobile devices or computer. You can Easily Stream & listen to this new “ FULL ALBUM: Passenger – Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) Zip File” free mp3 download” 320kbps, cdq, itunes, datafilehost, zip, torrent, flac, rar zippyshare fakaza Song below. DOWNLOAD ZIP/MP3. Full Album Tracklist. 1. Sword from the Stone (03:21) 2. Tip of My Tongue (03:01) 3. What You’re Waiting For (02:37) 4. The Way That I Love You (02:39) 5. Remember to Forget (03:38) 6. Sandstorm (05:01) 7. A Song for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (03:59) 8. Suzanne (04:15) 9. Nothing Aches Like a Broken Heart (04:16) 10. London in the Spring (03:01) 11. London in the Spring (Acoustic) (02:56) 12. Nothing Aches Like a Broken Heart (Acoustic) (03:17) 13. Suzanne (Acoustic) (04:05) 14. A Song for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Acoustic) (03:56) 15. Sandstorm (Acoustic) (04:10) 16. Remember to Forget (Acoustic) (03:36) 17. The Way That I Love You (Acoustic) (02:37) 18. What You’re Waiting For (Acoustic) (02:36) 19. Tip of My Tongue (Acoustic) (03:00) 20. Sword from the Stone (Acoustic) (03:33) Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) Album by Passenger. -

Most Requested Songs of 2015

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2015 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Ronson, Mark Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Swift, Taylor Shake It Off 5 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 6 Williams, Pharrell Happy 7 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 8 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 9 Sheeran, Ed Thinking Out Loud 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 12 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 13 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 14 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 15 Mars, Bruno Marry You 16 Maroon 5 Sugar 17 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 18 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 19 Legend, John All Of Me 20 B-52's Love Shack 21 Isley Brothers Shout 22 DJ Snake Feat. Lil Jon Turn Down For What 23 Outkast Hey Ya! 24 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 25 Beatles Twist And Shout 26 Pitbull Feat. Ke$Ha Timber 27 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 28 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 29 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 30 Trainor, Meghan All About That Bass 31 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 32 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 33 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 34 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 35 Bryan, Luke Country Girl (Shake It For Me) 36 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 37 Lmfao Feat. -

Miley Cyrus As the Posthuman: Media Sexualisation and the Intersections of Capitalism

Outskirts Vol. 38, 2018, 1-15 Miley Cyrus as the posthuman: Media sexualisation and the intersections of capitalism Haylee Ruwaard This article undertakes a semiotic deconstruction of Miley Cyrus’s image in two media photographs. I argue that she embodies a range of identities that simultaneously includes yet moves beyond sexualisation. Moral panic discourses about the impact of her influence can problematically view Cyrus through the lens of humanism where she is seen as highly sexualised and stereotypically gendered. This study suggests this outlook is limited. Rather, Cyrus can be perceived as a symbol of the posthuman as she integrates her biology with multiplying social subjectivities which fluctuate frequently. This integration creates many possible identities aside from those signifying sexualisation, which may ease or equalise current concerns about Cyrus’s influence. Yet, it cannot be ignored that Cyrus is operating within the confines of capitalism where identity diversification becomes highly profitable globally. As a result, this article examines the intersections of celebrity and capitalism. Introduction At the 2013 MTV Music Awards, former Disney child star and singer Miley Cyrus, shocked the world with a bizarre and highly sexualised performance that quickly went viral on the Internet. The then 20-year-old emerged from a giant teddy bear with her tongue out, surrounded by giant dancing bears, while performing a provocative medley of her song We Can’t Stop and singer Robin Thicke’s song Blurred Lines. Clearly eager to shed her saccharine child star image, Cyrus twerked and gyrated with Thicke, a man almost twice her age, clad in a flesh coloured bikini and holding an oversized foam finger with which she made frequent lewd sexualised gestures. -

Of 4 We Can't Stop - Miley Cyrus

We Can't Stop - Miley Cyrus We Can't Stop - Miley Cyrus (4/4 - Capo 4th fret) --------------------------- Suggested Picking Pattern: (Travis Pick) ------------------------- _ _ _ | | | | | | | e|-*-------*-----| B|-----*-------*-| G|---------------| D|-*-*---*---*---| A|-*-----*-------| E|-*-----*-------| | | Root note of the chord Examples: -------- C Em Am _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | e|-0-------0-----| |-0-------0-----| |-0-------0-----| B|-----1-------1-| |-----0-------0-| |-----1-------1-| G|---------------| |---------------| |---2-------2---| D|---2-------2---| |---2-------2---| |-0-----0-------| A|-3-----3-------| |---------------| |---------------| E|---------------| |-0-----0-------| |---------------| Chords: C, C, Em, Em, Am, Am, F, F (throughout) C ' It’s our party we can do what we want Em ' It’s our party we can say what we want Am ' It’s our party we can love who we want F ' We can kiss who we want we can screw who we want C C Red cups and sweaty bodies everywhere Em ' Hands in the air like we don’t care Am ' Cause we came to have so much fun now F ' Got somebody here might get some now C C If you’re not ready to go home Em ' Can I get a hell no Am ' Cause we gonna go all night F ' Till we see the sunlight alright Page 1 of 4 We Can't Stop - Miley Cyrus C ' So la da da di we like to party Em ' Dancing with Miley Am ' Doing whatever we want F ' This is our house, this is our rules C ' And we can’t stop Em ' And we won’t stop Am ' Can’t you see it’s we who own the night F ' Can’t you see it we