Judicial Review of Ouster Clause Provisions in the 1999 Constitution: Lessons for Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WALKER V. GEORGIA

Cite as: 555 U. S. ____ (2008) 1 THOMAS, J., concurring SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ARTEMUS RICK WALKER v. GEORGIA ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA No. 08–5385. Decided October 20, 2008 JUSTICE THOMAS, concurring in the denial of the peti- tion of certiorari. Petitioner brutally murdered Lynwood Ray Gresham, and was sentenced to death for his crime. JUSTICE STEVENS objects to the proportionality review undertaken by the Georgia Supreme Court on direct review of peti- tioner’s capital sentence. The Georgia Supreme Court, however, afforded petitioner’s sentence precisely the same proportionality review endorsed by this Court in McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U. S. 279 (1987); Pulley v. Harris, 465 U. S. 37 (1984); Zant v. Stephens, 462 U. S. 862 (1983); and Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U. S. 153 (1976), and described in Pulley as a “safeguard against arbitrary or capricious sentencing” additional to that which is constitu- tionally required, Pulley, supra, at 45. Because the Geor- gia Supreme Court made no error in applying its statuto- rily required proportionality review in this case, I concur in the denial of certiorari. In May 1999, petitioner recruited Gary Lee Griffin to help him “rob and kill a rich white man” and “take the money, take the jewels.” Pet. for Cert. 5 (internal quota- tion marks omitted); 282 Ga. 774, 774–775, 653 S. E. 2d 439, 443, (2007). Petitioner and Griffin packed two bicy- cles in a borrowed car, dressed in black, and took a knife and stun gun to Gresham’s house. -

Inequality and Development in Nigeria Inequality and Development in Nigeria

INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA Edited by Henry Bienen and V. P. Diejomaoh HOLMES & MEIER PUBLISHERS, INC' NEWv YORK 0 LONDON First published in the United States of America 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. 30 Irving Place New York, N.Y. 10003 Great Britain: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Ltd. 131 Trafalgar Road Greenwich, London SE 10 9TX Copyright 0 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. ALL RIGIITS RESERVIED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria. Selections. Inequality and development in Nigeria. "'Chapters... selected from The Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria."-Pref. Includes index. I. Income distribution-Nigeria-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Nigeria- Economic conditions- Addresses. essays, lectures. 3. Nigeria-Social conditions- Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Bienen. Henry. II. Die jomaoh. Victor P., 1940- III. Title. IV. Series. HC1055.Z91516 1981 339.2'09669 81-4145 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA ISBN 0-8419-0710-2 AACR2 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents Page Preface vii I. Introduction 2. Development in Nigeria: An Overview 17 Douglas Riummer 3. The Structure of Income Inequality in Nigeria: A Macro Analysis 77 V. P. Diejomaoli and E. C. Anusion wu 4. The Politics of Income Distribution: Institutions, Class, and Ethnicity 115 Henri' Bienen 5. Spatial Aspects of Urbanization and Effects on the Distribution of Income in Nigeria 161 Bola A veni 6. Aspects of Income Distribution in the Nigerian Urban Sector 193 Olufemi Fajana 7. Income Distribution in the Rural Sector 237 0. 0. Ladipo and A. -

15. Judicial Review

15. Judicial Review Contents Summary 413 A common law principle 414 Judicial review in Australia 416 Protections from statutory encroachment 417 Australian Constitution 417 Principle of legality 420 International law 422 Bills of rights 422 Justifications for limits on judicial review 422 Laws that restrict access to the courts 423 Migration Act 1958 (Cth) 423 General corporate regulation 426 Taxation 427 Other issues 427 Conclusion 428 Summary 15.1 Access to the courts to challenge administrative action is an important common law right. Judicial review of administrative action is about setting the boundaries of government power.1 It is about ensuring government officials obey the law and act within their prescribed powers.2 15.2 This chapter discusses access to the courts to challenge administrative action or decision making.3 It is about judicial review, rather than merits review by administrators or tribunals. It does not focus on judicial review of primary legislation 1 ‘The position and constitution of the judicature could not be considered accidental to the institution of federalism: for upon the judicature rested the ultimate responsibility for the maintenance and enforcement of the boundaries within which government power might be exercised and upon that the whole system was constructed’: R v Kirby; Ex parte Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1956) 94 CLR 254, 276 (Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Fullagar and Kitto JJ). 2 ‘The reservation to this Court by the Constitution of the jurisdiction in all matters in which the named constitutional writs or an injunction are sought against an officer of the Commonwealth is a means of assuring to all people affected that officers of the Commonwealth obey the law and neither exceed nor neglect any jurisdiction which the law confers on them’: Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth (2003) 211 CLR 476, [104] (Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ). -

SPECIAL REPORT on Nigeria's

Special RepoRt on nIgeria’s BENUe s t A t e BENUE STATE: FACTS AND FIGURES Origin: Benue State derives its name from the River Benue, the second largest river in Nigeria and the most prominent geographical feature in the state Date of creation: February 1976 Characteristics: Rich agricultural region; full of rivers, breadbasket of Nigeria. Present Governor: Chief George Akume Population: 5 million Area: 34,059 sq. kms Capital: Makurdi Number of local government: 23 Traditional councils: Tiv Traditional Council, headed by the Tor Tiv; and Idoma Traditional Council, headed by the Och’Idoma. Location: Lies in the middle of the country and shares boundaries with Cameroon and five states namely, Nasarawa to the north, Taraba to the east, Cross River and Enugu to the south, and Kogi to the west Climate: A typical tropical climate with two seasons – rainy season from April to October in the range of 150-180 mm, and the dry season from November to March. Temperatures fluctuate between 23 degrees centigrade to 31 degrees centigrade in the year Main Towns: Makurdi (the state capital), Gboko, Katsina-Ala, Adikpo, Otukpo, Korinya, Tar, Vaneikya, Otukpa, Oju, Okpoga, Awajir, Agbede, Ikpayongo, and Zaki-Biam Rivers: Benue River and Katsina Ala Culture and tourism: A rich and diverse cultural heritage, which finds expression in colourful cloths, exotic masquerades, music and dances. Benue dances have won national and international acclaim, including the Swange and the Anuwowowo Main occupation: Farming Agricultural produce: Grains, rice, cassava, sorghum, soya beans, beniseed (sesame), groundnuts, tubers, fruits, and livestock Mineral resources: Limestone, kaolin, zinc, lead, coal, barites, gypsum, Feldspar and wolframite for making glass and electric bulbs, and salt Investment policies: Government has a liberal policy of encouraging investors through incentives and industrial layout, especially in the capital Makurdi, which is served with paved roads, water, electricity and telephone. -

Proportionality As a Principle of Limited Government!

032006 02_RISTROPH.DOC 4/24/2006 12:27 PM PROPORTIONALITY AS A PRINCIPLE ! OF LIMITED GOVERNMENT ALICE RISTROPH† ABSTRACT This Article examines proportionality as a constitutional limitation on the power to punish. In the criminal context, proportionality is often mischaracterized as a specifically penological theory—an ideal linked to specific accounts of the purpose of punishment. In fact, a constitutional proportionality requirement is better understood as an external limitation on the state’s penal power that is independent of the goals of punishment. Proportionality limitations on the penal power arise not from the purposes of punishment, but from the fact that punishing is not the only purpose that the state must pursue. Other considerations, especially the protection of individual interests in liberty and equality, restrict the pursuit of penological goals. Principles of proportionality put the limits into any theory of limited government, and proportionality in the sentencing context is just one instance of these limitations on state power. This understanding of proportionality gives reason to doubt the assertion that determinations of proportionality are necessarily best left to legislatures. In doctrinal contexts other than criminal sentencing, proportionality is frequently used as a mechanism of judicial review to prevent legislative encroachments on individual rights and other exercises of excessive power. In the criminal sentencing context, a constitutional proportionality requirement should serve as a limit on penal power. Copyright © 2005 by Alice Ristroph. † Associate Professor, University of Utah, S.J. Quinney College of Law. A.B., Harvard College; J.D., Harvard Law School; Ph.D., Harvard University; L.L.M., Columbia Law School. -

Practical Guide on Admissibility Criteria

Practical Guide on Admissibility Criteria Updated on 1 August 2021 This Guide has been prepared by the Registry and does not bind the Court. Practical guide on admissibility criteria Publishers or organisations wishing to translate and/or reproduce all or part of this report in the form of a printed or electronic publication are invited to contact [email protected] for information on the authorisation procedure. If you wish to know which translations of the Case-Law Guides are currently under way, please see Pending translations. This Guide was originally drafted in English. It is updated regularly and, most recently, on 1 August 2021. It may be subject to editorial revision. The Admissibility Guide and the Case-Law Guides are available for downloading at www.echr.coe.int (Case-law – Case-law analysis – Admissibility guides). For publication updates please follow the Court’s Twitter account at https://twitter.com/ECHR_CEDH. © Council of Europe/European Court of Human Rights, 2021 European Court of Human Rights 2/109 Last update: 01.08.2021 Practical guide on admissibility criteria Table of contents Note to readers ........................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................ 7 A. Individual application ............................................................................................................. 9 1. Purpose of the provision .................................................................................................. -

Nigerian Current Law Review 2007 - 2010

NIGERIAN CURRENT LAW REVIEW 2007 - 2010 The JOURNAL OF THE NIGERIAN INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED LEGAL STUDIES © Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photo coping, recording or otherwise or stored in any retrieval system of any nature, without the written permission of the copyright holder. Published 2010 by Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies P.M.B. 12820 University of Lagos Campus, Akoka, Lagos, Nigeria ISSN: 0189-207X Printed by NIALS Press, Abuja ii NIGERIAN CURRENT LAW REVIEW 2007 – 2010 Editor-in-Chief Professor Epiphany Azinge, SAN Deputy Editor-in-Chief Professor Bolaji Owasanoye Editor Dr. (Mrs.) Francisca E. Nlerum Honorary Editorial Board 1. Hon. Justice Niki Tobi CON. 2. Professor M.A. Ajomo, FCIB, FCIArb, FNIALS, OFR 3. Emeritus Professor D. A. Ijalaye, SAN FNIALS 4. Professor E. I. Nwogugu FNIALS 5. Professor K. S. Chukkol 6. Hon. Justice Hassan Bubacar Jalao List of Contributors iii Contributors Articles Page Ayodele Gatta An Overview of the Plea of Non Est 1 Factum and Section 3 of the Illiterates Protection Law (1994) of Lagos State in Contracts Made by Illiterates in Nigeria Pam A, Adamu Anti-Dumping and Countervailing 42 Measures and Developing Countries: Recent Development Ikoni, U. D. Ph.D Causation and Scientific Evidence in 87 Product Liability: An Exploration of Contemporary Trends in Canada and some Lessons for Nigeria Tunde Otubu Land Reforms and the Future of the Land 126 Use Act in Nigeria Nlerum, F.E. -

Lions Over the Throne - the Udicj Ial Revolution in English Administrative Law by Bernard Schwartz N

Penn State International Law Review Volume 6 Article 8 Number 1 Dickinson Journal of International Law 1987 Lions Over The Throne - The udicJ ial Revolution In English Administrative Law by Bernard Schwartz N. David Palmeter Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Palmeter, N. David (1987) "Lions Over The Throne - The udJ icial Revolution In English Administrative Law by Bernard Schwartz," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 6: No. 1, Article 8. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol6/iss1/8 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lions Over the Throne - The Judicial Revolution in English Administrative Law, by Bernard Schwartz, New York and London: New York University Press, 1987 Pp. 210. Reviewed by N. David Palmeter* We learn more about our own laws when we undertake to compare them with those of another sovereign. - Justice San- dra Day O'Connor' In 1964, half a dozen years before Goldberg v. Kelly' began "a due process explosion" 3 in the United States, Ridge v. Baldwin4 be- gan a "natural justice explosion" in England. The story of this explo- sion - of this judicial revolution - is the story of the creation and development by common law judges of a system of judicial supervi- sion of administrative action that, in many ways, goes far beyond the system presently prevailing in the United States. -

Reflections on Preclusion of Judicial Review in England and the United States

William & Mary Law Review Volume 27 (1985-1986) Issue 4 The Seventh Anglo-American Exchange: Judicial Review of Administrative and Article 4 Regulatory Action May 1986 Reflections on Preclusion of Judicial Review in England and the United States Sandra Day O'Connor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Administrative Law Commons Repository Citation Sandra Day O'Connor, Reflections on Preclusion of Judicial Review in England and the United States, 27 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 643 (1986), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol27/iss4/4 Copyright c 1986 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr REFLECTIONS ON PRECLUSION OF JUDICIAL REVIEW IN ENGLAND AND THE UNITED STATES SANDRA DAY O'CONNOR* I. INTRODUCTION Lord Diplock said that he regarded "progress towards a compre- hensive system of administrative law ... as having been the great- est achievement of the English courts in [his] judicial lifetime." Inland Revenue Comm'rs v. National Fed'n of Self-Employed & Small Businesses Ltd., [1982] A.C. 617, 641 (1981). In the United States, we have seen comparable developments in our administra- tive law during the forty years since the enactment of the federal Administrative Procedure Act (APA) in 1946, as the federal courts have attempted to bring certainty, efficiency, and fairness to the law governing review of agency action while ensuring that agencies fulfill the responsibilities assigned to them by Congress and that they do so in a manner consistent with the federal Constitution. -

Judicial Review Scope and Grounds

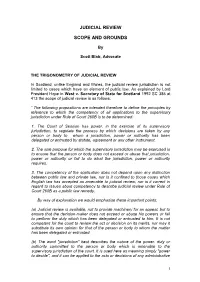

JUDICIAL REVIEW SCOPE AND GROUNDS By Scott Blair, Advocate THE TRIGONOMETRY OF JUDICIAL REVIEW In Scotland, unlike England and Wales, the judicial review jurisdiction is not limited to cases which have an element of public law. As explained by Lord President Hope in West v. Secretary of State for Scotland 1992 SC 385 at 413 the scope of judicial review is as follows: “ The following propositions are intended therefore to define the principles by reference to which the competency of all applications to the supervisory jurisdiction under Rule of Court 260B is to be determined: 1. The Court of Session has power, in the exercise of its supervisory jurisdiction, to regulate the process by which decisions are taken by any person or body to whom a jurisdiction, power or authority has been delegated or entrusted by statute, agreement or any other instrument. 2. The sole purpose for which the supervisory jurisdiction may be exercised is to ensure that the person or body does not exceed or abuse that jurisdiction, power or authority or fail to do what the jurisdiction, power or authority requires. 3. The competency of the application does not depend upon any distinction between public law and private law, nor is it confined to those cases which English law has accepted as amenable to judicial review, nor is it correct in regard to issues about competency to describe judicial review under Rule of Court 260B as a public law remedy. By way of explanation we would emphasise these important points: (a) Judicial review is available, not to provide machinery for an appeal, but to ensure that the decision-maker does not exceed or abuse his powers or fail to perform the duty which has been delegated or entrusted to him. -

Ministry of Justice Letterhead

The Right Honourable Robert Buckland QC MP Lord Chancellor & Secretary of State for Justice Sir Bob Neill MP Chair of the Justice Committee House of Commons MoJ Ref: 86346 SW1A 0AA 17 March 2021 Dear Bob, INDEPENDENT REVIEW OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW I am writing to let you and your Committee know that the Independent Review of Administrative Law has now concluded its work and the Panel’s report has been submitted to Ministers. Despite the circumstances under which the Panel worked, with the majority of their discussions having to take place virtually, they have produced an excellent, comprehensive report. I believe it goes much further than previous reviews in the use of empirical evidence and in consideration of some of the wider issues of Judicial Review, such as the evolving approach to justiciability and the arguments for and against codification. The Panel set out a number of recommendations for reform which the Government has considered carefully. I agree with the Panel’s analysis and am minded to take their recommendations forward. However, I feel that the analysis in the report supports consideration of additional policy options to more fully address the issues they identified. Therefore, I will very shortly be launching a consultation on a range of options which I want to explore before any final policy decisions are made. The IRAL call for evidence elicited many helpful submissions on Judicial Review and we are not seeking to repeat that exercise. Rather, we want consultees to focus on the measures in the consultation document. They set out our full range of thinking, which is still at an early stage, and respondents’ contributions to the consultation will help us decide which of the options to take forward. -

Ouster Clause – Legislative Blaze and Judicial Phoenix

Christ University Law Journal, 2, 1(2013), 21-51 ISSN 2278-4322|http://dx.doi.org/10.12728/culj.2.2 Ouster Clause: Legislative Blaze and Judicial Phoenix Sandhya Ram S A* Abstract If constitutionalism denotes obedience to the Constitution, the scheme for enforcement of obedience and invalidation of disobedience should be found in the Constitution itself. It is important that this scheme be clear and the task of enforcement be vested in a constitutional body. In such a situation, the question of custodianship i.e., who will ensure the rule of constitutionalism assumes prime importance, as any ambiguity regarding the same will result in conflicts uncalled for between legislature and judiciary. This conflict intensifies when judiciary determines the constitutionality of the legislations and the legislature defends by placing it in the „ouster clauses‟ within the Constitution to exclude the judicial determination. Judiciary counters by nullifying the legislative attempts through innovative interpretation. An attempt is made to study Article 31 B, the most prominent ouster clause in the Constitution of India barring judicial review of legislations and how the Indian judiciary retaliated to such legislative attempts and effectively curbed them. The study outlines the historical reasons which necessitated the insertion of Article 31 B in the Constitution and analyses the myriad implications of such an ouster clause within the Constitution. The constitutional basis of judicial review is studied to audit the justifiability of the open ended Ninth Schedule along with Article 31 B. A comparison between Article 31 B and the other ouster * Assistant Professor, V.M.Salgaocar College of Law, Miramar, Panaji, Goa; [email protected] 21 Sandhya Ram S A ISSN 2278-4322 clauses namely Articles 31 A and 31 C is also made, bringing out the effect and scope of Article 31 B.