Proportionality As a Principle of Limited Government!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WALKER V. GEORGIA

Cite as: 555 U. S. ____ (2008) 1 THOMAS, J., concurring SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ARTEMUS RICK WALKER v. GEORGIA ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA No. 08–5385. Decided October 20, 2008 JUSTICE THOMAS, concurring in the denial of the peti- tion of certiorari. Petitioner brutally murdered Lynwood Ray Gresham, and was sentenced to death for his crime. JUSTICE STEVENS objects to the proportionality review undertaken by the Georgia Supreme Court on direct review of peti- tioner’s capital sentence. The Georgia Supreme Court, however, afforded petitioner’s sentence precisely the same proportionality review endorsed by this Court in McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U. S. 279 (1987); Pulley v. Harris, 465 U. S. 37 (1984); Zant v. Stephens, 462 U. S. 862 (1983); and Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U. S. 153 (1976), and described in Pulley as a “safeguard against arbitrary or capricious sentencing” additional to that which is constitu- tionally required, Pulley, supra, at 45. Because the Geor- gia Supreme Court made no error in applying its statuto- rily required proportionality review in this case, I concur in the denial of certiorari. In May 1999, petitioner recruited Gary Lee Griffin to help him “rob and kill a rich white man” and “take the money, take the jewels.” Pet. for Cert. 5 (internal quota- tion marks omitted); 282 Ga. 774, 774–775, 653 S. E. 2d 439, 443, (2007). Petitioner and Griffin packed two bicy- cles in a borrowed car, dressed in black, and took a knife and stun gun to Gresham’s house. -

Practical Guide on Admissibility Criteria

Practical Guide on Admissibility Criteria Updated on 1 August 2021 This Guide has been prepared by the Registry and does not bind the Court. Practical guide on admissibility criteria Publishers or organisations wishing to translate and/or reproduce all or part of this report in the form of a printed or electronic publication are invited to contact [email protected] for information on the authorisation procedure. If you wish to know which translations of the Case-Law Guides are currently under way, please see Pending translations. This Guide was originally drafted in English. It is updated regularly and, most recently, on 1 August 2021. It may be subject to editorial revision. The Admissibility Guide and the Case-Law Guides are available for downloading at www.echr.coe.int (Case-law – Case-law analysis – Admissibility guides). For publication updates please follow the Court’s Twitter account at https://twitter.com/ECHR_CEDH. © Council of Europe/European Court of Human Rights, 2021 European Court of Human Rights 2/109 Last update: 01.08.2021 Practical guide on admissibility criteria Table of contents Note to readers ........................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................ 7 A. Individual application ............................................................................................................. 9 1. Purpose of the provision .................................................................................................. -

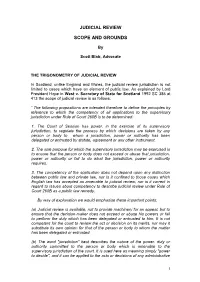

Judicial Review Scope and Grounds

JUDICIAL REVIEW SCOPE AND GROUNDS By Scott Blair, Advocate THE TRIGONOMETRY OF JUDICIAL REVIEW In Scotland, unlike England and Wales, the judicial review jurisdiction is not limited to cases which have an element of public law. As explained by Lord President Hope in West v. Secretary of State for Scotland 1992 SC 385 at 413 the scope of judicial review is as follows: “ The following propositions are intended therefore to define the principles by reference to which the competency of all applications to the supervisory jurisdiction under Rule of Court 260B is to be determined: 1. The Court of Session has power, in the exercise of its supervisory jurisdiction, to regulate the process by which decisions are taken by any person or body to whom a jurisdiction, power or authority has been delegated or entrusted by statute, agreement or any other instrument. 2. The sole purpose for which the supervisory jurisdiction may be exercised is to ensure that the person or body does not exceed or abuse that jurisdiction, power or authority or fail to do what the jurisdiction, power or authority requires. 3. The competency of the application does not depend upon any distinction between public law and private law, nor is it confined to those cases which English law has accepted as amenable to judicial review, nor is it correct in regard to issues about competency to describe judicial review under Rule of Court 260B as a public law remedy. By way of explanation we would emphasise these important points: (a) Judicial review is available, not to provide machinery for an appeal, but to ensure that the decision-maker does not exceed or abuse his powers or fail to perform the duty which has been delegated or entrusted to him. -

The Quest for Proportionality in the Discovery Rules of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duke Law Scholarship Repository Are We Insane? The Quest for Proportionality in the Discovery Rules of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Paul W. Grimm Albert Einstein defined insanity as “doing the same thing over and over again, and expecting different results.”1 For over thirty years, the federal rules of civil procedure have been serially amended to require federal trial judges to control pretrial discovery in civil cases to ensure that it is “proportional”—meaning that the costs to the parties are not unduly great given what is at stake in the litigation. And, for thirty years, lawyers, bar associations, clients and commentators have complained loudly that the federal judges have not done so. The Supreme Court has approved yet another series of civil rules changes, which took effect on December 1, 2015, that once more direct judges to ensure that discovery is proportional. But if the proportionality requirement already has been in the rules for over thirty years without inducing judges to fulfill their obligation to manage discovery, what makes this latest amendment requiring the exact same thing any more likely to achieve success? In short, why has achieving proportionality been such an elusive goal? Is it possible for judges to manage discovery so that it is proportional? If so, how are they to do so? And, if achieving proportionality is possible, why have judges failed to do so? Is it because they are resistant to doing what the rules require? Or are they willing to try, but they lack the knowledge or training to succeed in the task? These questions, and their answers, are the focus of this thesis. -

Judges and Discrimination: Assessing the Theory and Practice of Criminal Sentencing

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Judges and Discrimination: Assessing the Theory and Practice of Criminal Sentencing Author(s): Charles W. Ostrom ; Brian J. Ostrom ; Matthew Kleiman Document No.: 204024 Date Received: February 2004 Award Number: 98-CE-VX-0008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Judges and Discrimination Assessing the Theory and Practice of Criminal Sentencing Apprwed By: m Authored by: Charles W. Ostrom Michigan State University Brian J. Ostrom National Center for State Courts Matthew Kleiman National Center for State Courts With the cooperation of the Michigan Sentencing Commission and the Michigan Department of Corrections This report was developed under a grant from the National Institute of Justice (Grant 98-CE-VX-0008). The opinions andpoints of view in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute or the Michigan Sentencing Commission. 1 The sentencing decision is the symbolic keystone of the c~minaljustice system: in it, the conflicts between the goals of equal justice under the law and indvidualzedjustice with punishment tailored to the offender are played out, and sociely5s moral principles and highest vaiues-life and libedy-are interpreted and appled. -

Richard S. Frase* the Supreme Court's Disappointing Holdings in the California Three Strikes Cases Have Probably Led Many Obse

LIMITING EXCESSIVE PRISON SENTENCES UNDER FEDERAL AND STATE CONSTITUTIONS * Richard S. Frase INTRODUCTION The Supreme Court’s disappointing holdings in the California Three Strikes cases have probably led many observers to conclude that there are no effective constitutional limits on excessively long prison sentences. This Article argues the contrary, and makes three main points. First, any judgment of excessiveness (or disproportionality) re- quires a normative framework—“excessive” relative to what? The Court’s opinions have been very unhelpful in this regard, but three distinct proportionality principles are implicit in Eighth Amendment cases (and in many other areas of American, foreign, and interna- tional law). Litigators, courts, and scholars need to clearly state and make explicit use of these principles. As summarized below, and more fully discussed in my previous writings,1 three of the most im- portant and widespread examples of such principles are what I have called the limiting retributive, ends-benefits, and alternative-means proportionality principles. The second and third principles are grounded in utilitarian philosophy; thus, they apply even if a jurisdic- tion (with the Court’s apparent blessing) rejects retributive limits on lengthy prison terms designed to achieve crime control and other practical goals. Second, excessiveness, in one or more of the three senses dis- cussed in Part I, is the common theme which underlies all three clauses of the Eighth Amendment.2 Litigators, courts, and scholars should explicitly recognize and apply this theme in prison-duration cases applying the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause, drawing * Benjamin N. Berger Professor of Criminal Law, University of Minnesota. -

The Reasonableness and Proportionality Principle in Labour Law

THE REASONABLENESS AND PROPORTIONALITY PRINCIPLE IN LABOUR LAW Piera Loi Law Department, University of Cagliari, Italy The reasonableness and proportionality principle in labour law Piera Loi Law Department, University of Cagliari, Italy [email protected] Draft- not to be quoted Introduction The reasonableness and proportionality principle seems to have a growing importance in labour law. One of the first questions we should ask is what are the relations between these concepts. In the Italian constitutional tradition proportionality and reasonableness are strictly related, since the proportionality principle has always been considered as instrumental to the reasonableness principle- and the proportionality test is seen as part of the reasonableness test- whereas in the other EU legal systems and also in European case law the reasonableness principle is autonomous. The proportionality principle is in use in different areas of law, especially in constitutional and administrative law, and it’s aiming at controlling the exercise of public powers towards individuals. This unwritten constitutional principle developed by the German Constitutional Courts, finds its origins in the tradition of German public law. It was precisely the Prussian Supreme Court that established the principle in the field of police law1 and Georg Jellinek’s comment was that “the police may not kill a swallow with a cannon”. The principle requires that any restriction of individual freedom must be appropriate to the attainment of the objectives to be achieved. Any restrictive measures should not impose excessive limits on the freedom of the individual and must therefore be based on the principle of 1 Decision 9 of 14 June 1882, PROVG 353 reasonableness. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. In the Supreme Court of the United States STEPHEN M. SHAPIRO, O. JOHN BENISEK, AND MARIA B. PYCHA Petitioners, v. BOBBIE S. MACK AND LINDA H. LAMONE, Respondents. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI MICHAEL B. KIMBERLY Counsel of Record PAUL W. HUGHES JEFFREY S. REDFERN Mayer Brown LLP 1999 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 (202) 263-3127 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioners QUESTION PRESENTED The Three-Judge Court Act requires the conven- ing of three-judge district courts to hear a wide range of particularly important lawsuits, including consti- tutional challenges to the apportionment of congres- sional districts and certain actions under the Voting Rights Act, Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, Prison Litigation Reform Act, and Communications Act. The Three-Judge Court Act provides that a three-judge court shall be convened to hear such cases unless the single judge to whom the case is initially referred “determines that three judges are not required.” 28 U.S.C. § 2284(a), (b)(1). In Goosby v. Osser, 409 U.S. 512 (1973), this Court held that the Three-Judge Court Act “does not require the convening of a three-judge court when the [claim] is insubstantial.” Id. at 518. A claim is in- substantial “for this purpose” if it is “‘obviously friv- olous,’” “‘essentially fictitious,’” or “inescapably * * * foreclose[d]” by this Court’s precedents. Ibid. The question presented, which has divided the lower courts, is as follows: May a single-judge district court determine that a complaint covered by 28 U.S.C. -

Overview of Judicial Review

Overview of Judicial Review Richards Harwood & Wald 9 September 2010 Overview of Judicial Review 1. A general overview of judicial review can be divided into the following topics, of which the second (Grounds of Review) forms the focus of today’s presentation: (1) Procedural issues. (a) Introduction. (b) Pre-action conduct. (c) Protective Costs Orders. (d) Commencing a Claim. (e) The Acknowledgment of Service. (f) Permission. (g) Costs at the Permission stage. (h) Standing. (i) Alternative Remedies. (j) Time Limits. (k) Discretion to Refuse a Remedy. (2) Grounds of Review (a) Illegality (i) Doing an act with no legal authority (simple illegality). (ii) Misinterpreting the law governing the decision. (iii) Failure to retain a discretion by: (1) Improper delegation. (2) Fettering of discretion by adoption of over-rigid policy. (iv) Abuse of discretion: (1) Using a power for an improper purpose. 2 (2) Taking into account irrelevant considerations or failing to take into account relevant considerations. (b) Irrationality. (c) Procedural Impropriety. (3) Remedies (a) Prerogative Remedies: (i) Quashing Order (ii) Mandatory Order (iii) Prohibiting Order (b) Common Law Remedies: (i) Injunction (ii) Declaration (c) Pecuniary Remedies: (i) Damages (ii) Restitution. 3 Procedural Issues Introduction 2. A claim for judicial review is defined widely by CPR 54.1(2)(a) as “a claim to review the lawfulness of – (i) an enactment; or (ii) a decision, action or failure to act in relation to the exercise of a public function.” 3. The judicial review procedure must be used in a claim for judicial review when the Claimant is seeking a prerogative order (mandatory order, prohibiting order, or quashing order) or an injunction under s30 Supreme Court Act 1981 (restraining a person from acting in any office in which he is not entitled to act): CPR 54.2. -

Ousting Ouster Clauses: the Ins and Outs of the Principles Regulating the Scope of Judicial Review in Singapore

Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2020] 392–426 OUSTING OUSTER CLAUSES: THE INS AND OUTS OF THE PRINCIPLES REGULATING THE SCOPE OF JUDICIAL REVIEW IN SINGAPORE Thio Li-ann∗ How a court responds to an ouster clause or other attempts to curb its jurisdiction, which seeks to exclude or limit judicial review over a public law dispute, is a reflection of the judicial perception of its role within a specific constitutional order. Article 4 of the Singapore Constitution declares the supremacy of constitutional law over all other forms of law—whether statutory, common law or customary in origin. The courts have judicially declared various unwritten constitutional principles which are of particular relevance to the question of the scope of judicial review, particularly, the separation of powers and the rule of law. With comparative references where illuminating, this article examines the scope of judicial review in Singapore administrative law, in the face of legislative intent that it be partially truncated or wholly excluded, with a view to identifying and evaluating the factors that have been judicially considered relevant in ascertaining the legitimacy of an ouster clause, including the Article 93 judicial power clauses and the inter-play of other constitutional principles. I. Introduction: Legislative Intervention in the Realm of Judicial Review The law on ouster clauses, which shapes the scope of judicial review, may be seen as “a theatre of legislative-judicial engagement,”1 revealing how institutional actors view their role within a constitutional order, and the nature of administrative law within that polity. Courts have traditionally been hostile towards statutory attempts to exclude or restrict their supervisory jurisdiction, a facet of their general and inherent powers of adjudication, over jurisdictional excesses. -

Express and Implied Limits on Judicial Review: Ouster and Time Limit Clauses, the Prerogative Power, Public Interest Immunity

17 Express and implied limits on judicial review: ouster and time limit clauses, the prerogative power, public interest immunity 17.1 Introduction We have already seen that the expansion of judicial review is one conspicuous feature of English administrative law over recent decades. This chapter will, fi rst, be concerned with examining how far is it possible to exclude the jurisdiction of the courts by the careful drafting of objectively worded statutory ouster pro- visions, and by the use of subjective language allowing considerable discretion to the decision-taker. In particular, secondly, we will focus on two areas where implied, rather than express, limits are central: the prerogative power, and the use of public interest immunity by government and other bodies. This is important because, if in advance of any action it is recognised that the exclusion of the courts has been achieved, this is a clear signal to decision-takers that they may operate without fear of intervention by the courts at a later stage. However, judges are aware of their constitutional position, and particularly of the doctrine of the rule of law. The result is that they have been unwilling to permit any subordinate authority to obtain uncontrollable power which would exempt public authorities, or other bodies, from the jurisdiction of the courts, as this would be, theoretically, tantamount to opening the door to potentially dictatorial power. For example, strong opposition was expressed in political, judicial and academic circles to a recent proposal by the government to insert an Ouster Clause in the Asylum and Immigration Bill 2004 which sought to exclude entirely the jurisdiction of the courts in relation to the operation of the Asylum and Immigration Tribunal. -

Constitutional Law in an Age of Proportionality

TH AL LAW JO RAL VICKI C. JACKSON Constitutional Law in an Age of Proportionality ABSTRACT. Proportionality, accepted as a general principle of constitutional law by many countries, requires that government intrusions on freedoms be justified, that greater intru- sions have stronger justifications, and that punishments reflect the relative severity of the of- fense. Proportionality as a doctrine developed by courts, as in Canada, has provided a stable methodological framework, promoting structured, transparent decisions even about closely con- tested constitutional values. Other benefits of proportionality include its potential to bring con- stitutional law closer to constitutional justice, to provide a common discourse about rights for all branches of government, and to help identify the kinds of failures in democratic process warrant- ing heightened judicial scrutiny. Earlier U.S. debates over "balancing" were not informed by re- cent comparative experience with structured proportionality doctrine and its benefits. Many areas of U.S. constitutional law include some elements of what is elsewhere called proportionality analysis. I argue here for greater use of proportionality principles and doctrine; I also argue that proportionality review is not the answer to all constitutional rights questions. Free speech can benefit from categorical presumptions, but in their application and design pro- portionality may be relevant. The Fourth Amendment, which secures a "right" against "unrea- sonable searches and seizures," is replete with categorical rules protecting police conduct from judicial review; more case-by-case analysis of the "unreasonableness" or disproportionality of police conduct would better protect rights and the rule of law. "Disparate impact" equality claims might be better addressed through more proportionate review standards; Eighth Amendment review of prison sentences would benefit from more use of proportionality principles.