Determining the Founder of New Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De La Conversion À La Guérison Puritanisme, Psychothérapies, Développement Personnel

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense École doctorale Économie, Organisations, Société Laboratoire Sophiapol De la conversion à la guérison Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel Thèse Pour obtenir le grade de Docteur en sciences humaines et sociales, mention sociologie Soutenue le 29 mai 2013 par Pierre Prades Sous la direction d’Alain Caillé, professeur des uni@versités, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense Jury M. Hubert BOST, directeur de recherche, École Pratique des Hautes Études M. Alain CAILLÉ, professeur émérite, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense Mme Jacqueline CARROY, directeur d’études, École des Hautes Études en Sciences sociales M. Stéphane HABER, professeur des universités, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense Mme Roberte HAMAYON, directeur d’études, École Pratique des Hautes Études De la conversion à la guérison. Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel II De la conversion à la guérison. Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense École doctorale Économie, Organisations, Société Laboratoire Sophiapol De la conversion à la guérison Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel Pierre Prades 29 mai 2013 III De la conversion à la guérison. Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel IV De la conversion à la guérison. Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel À Brigitte, généreuse et patiente mécène, dont l’indulgente bienveillance m’a soutenu durant de si longues années, et sans laquelle je n’aurais pu ni entreprendre ni réaliser ce projet, À Jeanne, lectrice attentive et critique éclairée, À Louis, pour l’émulation, À mon père, avec le regret d’avoir tant tardé, et à ma mère, qui a attendu avec confiance. -

Emma Curtis Hopkins Bible Interpretations Fourth Series: Psalms and Daniel, 2011, 172 Pages, Emma Curtis Hopkins, 0945385544, 9780945385547, Wisewoman Press, 2011

Emma Curtis Hopkins Bible Interpretations Fourth Series: Psalms and Daniel, 2011, 172 pages, Emma Curtis Hopkins, 0945385544, 9780945385547, WiseWoman Press, 2011 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/14dsEht http://www.abebooks.com/servlet/SearchResults?sts=t&tn=Emma+Curtis+Hopkins+Bible+Interpretations+Fourth+Series%3A+Psalms+and+Daniel&x=51&y=16 These Bible Interpretations were given during the early eighteen nineties at the Christian Science Theo-logical Seminary at Chicago, Illinois. This Seminary was independent of the First Church of Christ Scien-tist in Boston, Mass. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1uOmD9Q http://bit.ly/1rdwmYx Emma Curtis Hopkins Bible Interpretations Third Series Isaiah 11:1-10 to Isaiah 40:1-10, Emma Curtis Hopkins, 2010, Religion, 184 pages. Given in Chicago in the late 1880's.. Emma Curtis Hopkins Drops of Gold A Metaphysical Daybook, Emma Curtis Hopkins, 2010, Body, Mind & Spirit, 384 pages. Drops of Gold was originally published in 1891, and are distillations of the principals found in all of Emma's works. These daily inspirations are for each day of the year. The Complete Writings, Volume 1 , Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, 1988, Religion, 436 pages. Genesis , Emma Curtis Hopkins, May 1, 2012, Religion, 158 pages. These Lessons were published in the Inter-Ocean Newspaper in Chicago, Illinois during the eighteen nineties. Each passage opens your consciousness to a new awareness of the. Unveiling Your Hidden Power Emma Curtis Hopkins' Metaphysics for the 21st Century, Ruth L. Miller, 2005, Body, Mind & Spirit, 203 pages. "Emma Curtis Hopkins was the teacher of teachers, the woman who taught the founders of Unity, Divine Science, Church of Truth and Religious Science -- the woman who invented. -

List of New Thought Periodicals Compiled by Rev

List of New Thought Periodicals compiled by Rev. Lynne Hollander, 2003 Source Title Place Publisher How often Dates Founding Editor or Editor or notes Key to worksheet Source: A = Archives, B = Braden's book, L = Library of Congress If title is bold, the Archives holds at least one issue A Abundant Living San Diego, CA Abundant Living Foundation Monthly 1964-1988 Jack Addington A Abundant Living Prescott, AZ Delia Sellers, Ministries, Inc. Monthly 1995-2015 Delia Sellers A Act Today Johannesburg, So. Africa Association of Creative Monthly John P. Cutmore Thought A Active Creative Thought Johannesburg, So. Africa Association of Creative Bi-monthly Mrs. Rea Kotze Thought A, B Active Service London Society for Spreading the Varies Weekly in Fnded and Edited by Frank Knowledge of True Prayer 1916, monthly L. Rawson (SSKTP), Crystal Press since 1940 A, B Advanced Thought Journal Chicago, IL Advanced Thought Monthly 1916-24 Edited by W.W. Atkinson Publishing A Affirmation Texas Church of Today - Divine Bi-monthly Anne Kunath Science A, B Affirmer, The - A Pocket Sydney, N.S.W., Australia New Thought Center Monthly 1927- Miss Grace Aguilar, monthly, Magazine of Inspiration, 2/1932=Vol.5 #1 Health & Happiness A All Seeing Eye, The Los Angeles, CA Hall Publishing Monthly M.M. Saxton, Manly Palmer Hall L American New Life Holyoke, MA W.E. Towne Quarterly W.E. Towne (referenced in Nautilus 6/1914) A American Theosophist, The Wheaton, IL American Theosophist Monthly Scott Minors, absorbed by Quest A Anchors of Truth Penn Yan, NY Truth Activities Weekly 1951-1953 Charlton L. -

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

The 10 Core Concepts of Science of Mind Dr. Ernest Holmes, The

The 10 Core Concepts of Science of Mind Dr. Ernest Holmes, the founder of Religious Science and developer of the Science of Mind philosophy, gave this definition for his teaching: Religious Science is a synthesis of the laws of science, opinions of philosophy, and revelations of religion, applied to human needs and the aspirations of humankind. Dr. Ernest Holmes was a mystic who found God in the silence. Going within and experiencing God in the deepest part of himself was his spiritual practice. His spirituality was reflected in his living; he believed he was one with God, and he experienced that oneness in all that he did. As important as the mystical experience was to Dr. Holmes, he also believed that religion had to be applied to everyday life problems, as an integral part of the walk of faith. Wholeness involved the Presence, yes, but also the Power -- the two faces of the dual nature of God. Dr. Holmes developed the Science of Mind philosophy to reflect his twin beliefs that the inner experience of God gave entry to the Power of God and that changing the way we think about our conditions causes the Power of the Universe to change those conditions to make our lives better. Science of Mind identifies the spiritual principles that apply equally to everyone in every situation, and it teaches us how to use them for our advantage. In their 1993 revision of the Foundational Class curriculum, Religious Science educators demonstrated that the Science of Mind philosophy is based on 10 Core Concepts that serve as the organizing principles of the Universe. -

HTS 140: History of New Thought & Unity

Syllabus HTS 140: History of New Thought & Unity Course Overview Course Instructor Name Rev. Karren Scapple Virtual Office Hours Tuesdays 5-6 pm, immediately after class and by appointment. Telephone 816-525-4059 E-Mail [email protected] Response Time Within 24 hours of call or email unless otherwise indicated through Policy automatic message Course Description The History of New Thought & Unity explores the origin and development of the ideas, beliefs and practices that characterize the New Thought movement. Particular attention is placed on the history and development of Unity. Course Learning Objectives By the end of the course learners will be able to: • Explain principles and main influences of the New Thought movement. • Identify some of the key people and major events in the development of both the New Thought and Unity spiritual movements. • Examine the development of Unity School of Christianity and Association of Unity Churches and their respective missions. Required Book • Vahle, Neal. The Unity Movement: Its Evolution and Spiritual Teachings. Philadelphia, PA: Templeton Press, 2002. Recommended Books • Braden, Charles S. Spirits in Rebellion: The Rise and Development of New Thought. Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University, 1963. • Hicks, Mark. Background of New Thought. TruthUnity.net, 2014. https://www.truthunity.net/courses/mark-hicks/background-of-new-thought • Larson, Martin A. New Thought Religion: A Philosophy for Health, Happiness, and Prosperity. New York: Philosophical Library, 1985. • Mosley, Glenn. New Thought, ancient wisdom : the history and future of the New Thought movement. Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press, 2006. 200 Unity Circle North, Suite A, Lee’s Summit, MO 64086 816.524.7414 www.uwsi.org / www.unityworldwideministries.org 1 • Shepherd, Thomas. -

Christian Scientists in the Courts

Christianity Case Study – Minority in America 2018 Christian Scientists in the Courts Since independence, Christians have always been a majority of the US population, so it may seem curious to call American Christians a minority. However, some Christians have been rejected by the wider US Christian community and are thus “minoritized”—meaning they are treated as if they do not belong to the majority. Christians from such groups have often claimed they face persecution or hardships. One of these groups is the Christian Scientists. This American born The Mother Church of the Church of Christ, religion began in 1879 in Massachusetts, with Scientist, in Boston, Massachusetts. Photo by Rizka, teachings of Mary Baker Eddy, who wrote a book July 15, 2014. Wikimedia Commons: called Science and Health, which became a holy http://bit.ly/2s6MpcU. text to Christian Scientists along with the Bible. Note on this Case Study: The text describes the material world as an 1 illusion, and the real world as totally spiritual. Religions are embedded in culture, and are deeply impacted by questions of power. While Based in this belief, Christian Scientists generally reading this case study about Christianity and view disease and illness as a mental error, not a life as a member of a minority religion in America, think about who is in power and who physical problem. Thus, to heal ailments, they lacks power. Is someone being oppressed? Is usually rely on prayer rather than medical care. someone acting as an oppressor? How might When members get sick, they call for a “Christian religious people respond differently when they Science Practitioner”—a person certified by the are in a position of authority or in a position of Church, but with no medical credentials—to pray oppression? over them for healing in what believers call a As always, when thinking about religion and “treatment.” They usually refuse to vaccinate power, focus on how religion is internally their children, take medicine of any kind, or see a diverse, always evolving and changing, and doctor, even for emergencies. -

Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications a Finding Aid

The Mary Baker Eddy Library Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications a finding aid mbelibrary.org [email protected] 200 Massachusetts Ave. Boston, MA 02115 617-450-7218 Collection Description Collection #: 11 MBE Collection Title: Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications Creator: Eddy, Mary Baker Inclusive Dates: 1856-1910, 1912 Extent: 15.25 __LF Provenance: Transferred from Mary Baker Eddy’s last home at Chestnut Hill (400 Beacon St.) on the following dates: August 26, 1932, June 1938, May 7, 1951, and April 1964. Copyright Materials in the collection are subject to applicable copyright laws. Restrictions: Scope and Content Note Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications consists of over 600 items chiefly from Mary Baker Eddy's files from her last residence at Chestnut Hill. All of the items in the collection were published during Eddy’s lifetime except "The Children’s Star" dated October 1912 (PE00030) and "A Funeral Sermon: Occasioned by the death of Mr. George Baker," 1679 (PE00109). Many of the items were annotated, marked, and requested by Eddy to be saved (see PE00055.033, PE00185-PE00189, PE00058.127). The collection consists of two series: Series I, Pamphlets and Series II, Serial Publications. Series I, Pamphlets, consists mostly of the writings of Mary Baker Eddy as small leaflets or booklets. The series also consists of writings by persons significant to the history of Christian Science (Edward A. Kimball, Bliss Knapp, Septimus J. Hanna, etc.). Some of the pamphlets were never published such as "Why is it?" by Mary Baker Eddy (PE00262). Pamphlets also include "Christ My Refuge" sheet music (PE00032) and a Science and Health advertisement (PE00220). -

Pentecostalism As Religion of Periphery: an Analysis of Brazilian Case

Pentecostalism as religion of periphery: an analysis of Brazilian case Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor philosophae (Dr. phil.) eingerichtet an der Philosophischen Fakultät III der Humboldt Universität zu Berlin Von Master of Science Brand Arenari Präsident der Humboldt Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Jan-Hendrick Olbertz Dekanin der Philosophen Fakultät III Prof. Dr. Julia von Blumenthal Gutachter: 1: Klaus Eder 2: Jessé Freire Souza Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 12.12.2013 1 Abstract All the analyses we have developed throughout this dissertation point to a central element in the emergence and development of Pentecostalism, i.e., its raw material – the promise of religious salvation – is based on the idea of social ascension, particularly the ascension related to the integration of sub-integrated social groups to the dynamics of society. The new religion that arose in the USA focused on the needs and social dramas that were specific of the newly arrived to the urban world of the large North-American cities, those who inhabited the periphery of these cities, those that were socially, economically, and ethnically excluded from the core of society. We also analysed how the same social drama was the basis for the development of Pentecostalism in Latin America and, especially, in Brazil. In this country, a great mass of excluded individuals, also residents of urban peripheries (which proves the non-traditional and modern characteristic of these sectors), found in Pentecostalism the promises of answers to their dramas, mainly the anxiety to become integrated to a world in which they did not belong before. Such integration was embedded in the promise present in the modernity of social ascension. -

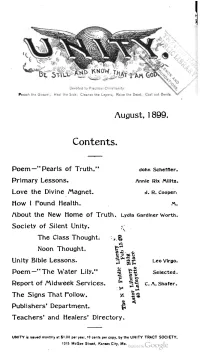

1899-08-Unity.Pdf

Devoted to Practical Christianity: Preach the Gospei; Heal the Sick; Cleanse the Lepers; Raise the Dead; Cast out Devils. August, 1899. Contents. Poem-"Pearls of Truth." dohn Scheffler. Primary Lessons. Annie Rlx ftllltz. Love the Divine A\agnet. d. R. Cooper. How I Found Health. About the New Home of Truth. Lydia Gardiner worth Society of Silent Unity. v The Class Thought. Noon Thought. 5 a ecu Unity Bible Lessons. Leo Virgo. Selected. Poem-"The Water Lily." fit e i> Report of Midweek Services C* £ ° C A. Shater. The Signs That follow. < Publishers' Department. I Teachers' and Healers' Directory UNITY it iuued monthly at $1.00 per year, 10 cent! per copy, by the UNITY TRACT SOCIETY, 1315 McQee Street, Kansas City, Mo. Booklets by Leo Virgo. Booklets Philosophy of Denial 15 by H. Emilie Cady. Direction* (or Beginner*, with Six Days' Course of Treatment to Points for Members of Silent Unity 10 Finding the Christ in Ourselves 15 The Church of Christ 10 Oneness with God. ( Talks on Truth as 5 Flesh Eating Metaphysically Considered, .05 Neither Do 1 Condemn Thee, i Jesus Chrisrs Atonement 05 Trusting and Resting. 10 Giving and Receiving 05 Loose Him and Let Him Go, t The Unreality of Matter 05 God's Hand. f IO Truths of Being 05 Address orders to FOR SAIM BV UNITY TRACT SOCIETY, UNITY TRACT SOCIETY, 131S McGee St.. 1315 McGeeSt.. KANSAS CITV. MlssorM. KANSAS CITV. MISSOIRI. Scientific Lessons in Eeing. Love: The Supreme Gift. BV EDITH A. MARTIN. BT HENRY DRUMMONI). Six clear-cut lessons in the Truth of Being that appeal especially to literary This is a souvenir edition of this always people and t h o s e who want the logic of metaphysics. -

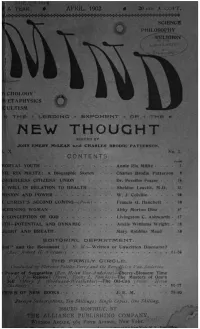

Mind V10 1902

i~ i?}{€'%ic‘RE ii ' DOMINION AND POWE] AN IMPORTANT VOLUME or STUDIES IN SPIRITUAL SCIENCE. ‘ This is a large work, probably the most comprehensive of author'spublications. embracingan epitome of the New Thought tc ing on every subject of vital moment in human development. indispensable to all who desire accurate knowledge of the New B physical Movement. Following is a list of the subjects discussec appropriate "Meditation ” being appended to most of the chapters Tn! Sxcxn or Powzn. Lovz IN CHARACTER BUILDING. Tau: PLANII.s or DEVELOPMENT. PRAYER. THE T33: or KNOWLEDGE. BREATH. TH: PURPOSE 0!‘ LIFE. Suva-zss. Tm: MISTAKES or LIFE. THE EQUALITY or nu Sans. FINDING ONI-:‘s SELF. MARRIAGE. How To CONSERVE Foncz. 7[‘Iu~: RIGHTS or CHXLDRIN. FAITH IN CIIAxAcrIm BUILDING. IMMOR’l‘ALl'l‘\’. Hon‘. IN CHARACTER BUlLl)ll\'G. Do,\uNIoN AND Pawn. PRICE. $1.00, POST-PAID. THE WILL TO BE WEL: This work relates chiefly to the /Imlfng aspect—philosophy practise—of Spiritual Science. It throws much new light 011 the through which alone Health, Happiness, and Success in all legitii undertakings are to be secured, and discusses in addition a numb! topics pertaining to the New Thought teaching in general. Som the chapters bear the following titles: WHAT ‘nu: NEW THOUGHT STANDS Fox. TIIINc.s Wonrn REMEMBERING. THE LAWS 01-‘ HEALTH. Tm; MIssIoN OF JI-;sus. MENTAL IN!-'LUE‘.\'CES. Tm: LAW 01-‘ A’l“l'l<AC'l‘lON. Tm: U.\'l'l‘Y or LIFE. MAN: PAST. PRESENT. AND FUTUI DEMAND AND SUPPLY. Tm; RELIGION or CHRIST. -

The Eddy-Hopkins Paradigm: a ‘Metaphysical Look’ at Their Historic Relationship

The Eddy-Hopkins Paradigm: A ‘Metaphysical Look’ at Their Historic Relationship John K. Simmons Western Illinois University In her noteworthy quest to establish Emma Curtis Hopkins as the founder of New Thought, Gail M. Harley revisits the varying perspectives on the falling out between Mary Baker Eddy and Emma Curtis Hopkins.1 Hopkins’ departure from the Christian Science establishment is, indeed, a critical event in the development of New Thought because this gifted and inspired mystic went on to teach a veritable Who’s Who of New Thought leaders, including Annie Rix Militz of Homes of Truth, Malinda Cramer of Divine Science, Charles Fillmore of Unity School of Christianity and Ernest Holmes of Religious Science.2 Historians plumping the depths of early New Thought history are not entirely sure what prompted the break-up between Eddy and Hopkins; reasons range from financial disagreements, to Hopkins’ eclectic attitude towards religious truth, to Eddy’s own paranoia regarding suspected enemies out to steal her metaphysical revelations and take credit for them. From an academic perspective, all of the above are plausible, and likely a multi-fragranced ill wind blew the two highly charged personalities apart. Historical scholarship, however, can be limited by its own self-imposed, Newtonian hermeneutical framework. Characters are identified in any historical drama, events are analyzed, then logical assumptions are made and conclusions drawn in explaining past events. Understandably, historians using this time-honor methodology would chronicle the rich but short and seemingly dysfunctional relationship between these two talented metaphysical teachers using an interpretive framework that focuses on unique personalities with disparate agendas.