10 Ellen Terry the Art of Performance and Her Work in Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dame Ellen Terry GBE

Dame Ellen Terry GBE Key Features • Born Alice Ellen Terry 27 February 1847, in Market Street, Coventry • Married George Frederic Watts, artist 20 February 1864 in Kensington. Separated 1864. Divorced 13 March 1877 • Eloped with Edward William Godwin, architect in 1868 with whom she had two children – Edith (b1869) and Edward Gordon (b1872). Godwin left Ellen in early 1875. • Married Charles Kelly, actor 21 November 1877 in Kensington. Separated 1881. Marriage ended by Kelly’s death on 17 April 1885. • Married James Carew, actor 22 March 1907 in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA. Unofficially separated 1909. • Died 21 July 1928 Smallhythe Place. Funeral service at Smallhythe church. Cremation at Golders Green Crematorium, London. Ashes placed in St Paul’s Covent Garden (the actors’ church). Urn on display on south wall (east end). A brief marital history Ellen Terry married three times and, between husbands one and two, eloped with the man who Ellen Terry’s first marriage was to the artist G F Watts. She was a week shy of 17 years old, young and exuberant, and he was a very neurotic and elderly 46. They were totally mismatched. Within a year he had sent her back to her family but would not divorce her. When she was 21, Ellen Terry eloped with the widower Edward Godwin and, as a consequence, was estranged from her family. Ellen said he was the only man she really loved. They had two illegitimate children, Edith and Edward. The relationship foundered after 6 or 7 years when they were overcome by financial problems resulting from over- expenditure on the house that Godwin had designed and built for them in Harpenden. -

![Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6681/theater-souvenir-programs-guide-1881-1979-256681.webp)

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979] RBC PN2037 .T54 1881 Choose which boxes you want to see, go to SearchWorks record, and page boxes electronically. BOX 1 1: An Illustrated Record by "The Sphere" of the Gilbert & Sullivan Operas 1939 (1939). Note: Operas: The Mikado; The Goldoliers; Iolanthe; Trial by Jury; The Pirates of Penzance; The Yeomen of the Guard; Patience; Princess Ida; Ruddigore; H.M.S. Pinafore; The Grand Duke; Utopia, Limited; The Sorcerer. 2: Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1960). Note: 26th Anniversary of the Glyndebourne Festival, operas: I Puritani; Falstaff; Der Rosenkavalier; Don Giovanni; La Cenerentola; Die Zauberflöte. 3: Parts I Have Played: Mr. Martin Harvey (1881-1909). Note: 30 Photographs and A Biographical Sketch. 4: Souvenir of The Christian King (Or Alfred of "Engle-Land"), by Wilson Barrett. Note: Photographs by W. & D. Downey. 5: Adelphi Theatre : Adelphi Theatre Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "Tina" (1916). 6: Comedy Theatre : Souvenir of "Sunday" (1904), by Thomas Raceward. 7: Daly's Theatre : The Lady of the Rose: Souvenir of Anniversary Perforamnce Feb. 21, 1923 (1923), by Frederick Lonsdale. Note: Musical theater. 8: Drury Lane Theatre : The Pageant of Drury Lane Theatre (1918), by Louis N. Parker. Note: In celebration of the 21 years of management by Arthur Collins. 9: Duke of York's Theatre : Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "The Admirable Crichton" (1902), by J.M. Barrie. Note: Oil paintings by Chas. A. Buchel, produced under the management of Charles Frohman. 10: Gaiety Theatre : The Orchid (1904), by James T. Tanner. Note: Managing Director, Mr. George Edwardes, musical comedy. -

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

Irving Room David Garrick (1717-1779) Nathaniel Dance-Holland (1735-1811) (After) Oil on Canvas BORGM 00609

Russell-Cotes Paintings – Irving Room Irving Room David Garrick (1717-1779) Nathaniel Dance-Holland (1735-1811) (after) Oil on canvas BORGM 00609 Landscape with a Cow by Water Joseph Jefferson (1829-1905) Oil on canvas BORGM 01151 Sir Henry Irving William Nicholson Print Irving is shown with a coat over his right arm and holding a hat in one hand. The print has been endorsed 'To My Old Friend Merton Russell Cotes from Henry Irving'. Sir Henry Irving, Study for ‘The Golden Jubilee Picture’, 1887 William Ewart Lockhard (1846-1900) Oil in canvas BORGM 01330 Russell-Cotes Paintings – Irving Room Sir Henry Irving in Various Roles, 1891 Frederick Barnard (1846-1896) Ink on paper RC1142.1 Sara Bernhardt (1824-1923), 1897 William Nicholson (1872-1949) Woodblock print on paper The image shows her wearing a long black coat/dress with a walking stick (or possibly an umbrella) in her right hand. Underneath the image in blue ink is written 'To Sir Merton Russell Cotes with the kind wishes of Sara Bernhardt'. :T8.8.2005.26 Miss Ellen Terry, Study for ‘The Golden Jubilee Picture’, 1887 William Ewart Lockhart (1846-1900) Oil on canvas BORGM 01329 Theatre Poster, 1895 A theatre poster from the Borough Theatre Stratford, dated September 6th, 1895. Sir Henry Irving played Mathias in The Bells and Corporal Brewster in A Story of Waterloo. :T23.11.2000.26 Russell-Cotes Paintings – Irving Room Henry Irving, All the World’s a Stage A print showing a profile portrait of Henry Irving entitled ‘Henry Irving with a central emblem of a globe on the frame with the wording ‘All The World’s A Stage’ :T8.8.2005.27 Casket This silver casket contains an illuminated scroll which was presented to Sir Henry Irving by his friends and admirers from Wolverhampton, in 1905. -

A Lively Theatre There's a Revolution Afoot in Theatre Design, Believes

A LIVELY THEatRE There’s a revolution afoot in theatre design, believes architectural consultant RICHARD PILBROW, that takes its cue from the three-dimensional spaces of centuries past The 20th century has not been a good time for theatre architecture. In the years from the 1920s to the 1970s, the world became littered with overlarge, often fan-shaped auditoriums that are barren in feeling and lacking in intimacy--places that are seldom conducive to that interplay between actor and audience that lies at the heart of the theatre experience. Why do theatres of the 19th century feel so much more “theatrical”? And why do so many actors and audiences prefer the old to the new? More generally, does theatre architecture really matter? There are some that believe that as soon as the house lights dim, the audience only needs to see and hear what happens on the stage. Perhaps audiences don’t hiss, boo and shout during a performance any more, but most actors and directors know that an audience’s reaction critically affects the performance. The nature of the theatre space, the configuration of the audience and the intimacy engendered by the form of the auditorium can powerfully assist in the formation of that reaction. A theatre auditorium may be a dead space or a lively one. Theatres designed like cinemas or lecture halls can lay a dead hand on the theatre experience. Happily, the past 20 years have seen a revolution in attitude to theatre design. No longer is a theatre only a place for listening or viewing. -

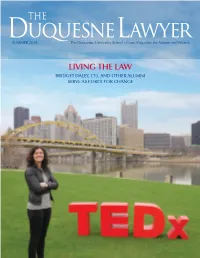

Living the Law Bridget Daley, L’13, and Other Alumni Serve As Force for Change Message from the Dean

THE SUMMER 2018 The Duquesne University School of Law Magazine for Alumni and Friends LIVING THE LAW BRIDGET DALEY, L’13, AND OTHER ALUMNI SERVE AS FORCE FOR CHANGE MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN Dean’s Message Congratulations to our newest alumni! Duquesne Law read about a new faculty/student mentorship program, which celebrated the 104th commencement on May 25 with the Class was made possible with alumni donations. You will also read of 2018 and their families, friends and colleagues. These J.D. and about alumni who are serving their communities in new ways, LL.M. graduates join approximately 7,800 Duquesne Law alumni often behind the scenes and with little fanfare, taking on pro residing throughout the world. bono cases, volunteering at nonprofit organizations, coordinating We all can be proud of what our graduates have community services and starting projects to help individuals in accomplished and the opportunities they have. Many of these need. You will discover how Duquesne Law is expanding diversity accomplishments and opportunities have been made possible and inclusion initiatives and read about new faculty roles in the because of you, our alumni. Indeed, our alumni go above and community as well as new scholarly works. Finally, you will read beyond to help ensure student success here. Colleagues in the about student achievements and the amazing work of student law often share with me that the commitment of Duquesne Law organizations here. alumni is something special! I invite you to be in touch and to join us for one of our Thank you most sincerely for all that you do! Whether you alumni events. -

The Return of Elizabeth: William Poel's Hamlet and the Dream Of

ঃਆઽࢂٷணপ࠙ 제16권 1호 (2008): 201-220 The Return of Elizabeth: William Poel’s Hamlet and the Dream of Empire Yeeyon Im (Yonsei University) 1. Translation and Authenticity There would be no dispute that few works of art have been ‘translated’ more widely than some plays in the Shakespeare canon. With a Shakespeare play, translation does not confine itself to language alone; its theatrical mode also undergoes a transformation when it is staged in a new cultural environment. Odd it may sound, Shakespeare has been translated even in England. It was Harley Granville-Barker who first emphasized the temporal distance between Shakespeare’s plays and the modern audience that needs to be translated: “The literature of the past is a foreign literature. We must either learn its language or suffer it to be translated”(7). Elizabethan plays “are like music written to be performed upon an 202 Yeeyon Im instrument now broken almost beyond repair”(9). Shakespeare’s plays, their putative universality notwithstanding, underwent changes and adaptations to suit the demands of different times. Shakespeare was ‘translated’ in terms of theatre as well. Anachronism was essential on the Elizabethan stage, which accommodated the fictional world of drama as well as the reality of the audience’s everyday life through presentation and representation. Elizabethan anachronism gave way to a more accurate representation of the dramatic world in the illusionist proscenium stage of the Victorian age. At present, modern directors are at liberty to ‘translate’ Shakespeare’s plays virtually in any period and style as they wish; it took an iconoclastic experimental spirit to break with the long‐standing Victorian tradition of archaeologically correct and pictorially spectacular staging. -

Henry Irving in England and America 1838-84

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES il -.;^ >--i ; . An?' Mi:-''' 4 ,. 'f V '1 \ \v\V HENRY IRVING. y^wn. «. /i/ur€e?ytayi/i Oy, J^f ..><? PPa/^»^. HENRY IRVIN.G IN ENGLAND and AMERICA 1838-84 BY FREDERIC DALY ' This ahozie all : To thine own self he true i Ami it mustfollow, as the niglit the day, Thou canst not then befalse to any )iian." Shakespeare " ' PeiseTerance keeps honour bright.' Do your duty. Be fatthfnl to the /inblic to "whom we all appeal, and that public loill be faitliful to you.'— Henky Irving ]] riH VIGNETTE PORTRAIT ETCHED DY AD. LALAUZE T. FISHER UNWIN 26 PATERNOSTER SQUARE 1884 " ^5 IN A MIRROR, WE SEE IN FLA YS IVHA T IS BECOMING IN A SERVANT, WHAT IN A LORD, WHAT BECOMES THE YOUNG, AND WHA7 THE OLD. CHRISTIANS SHOULD NOT ENTIRELY FLEE FROM COMEDIES, BECAUSE NOW AND THEN THERE ARE COARSE MATTERS IN THEM. I OR THE SAME REASON J IE MIGHT CEASE TO READ THE BIBLE.''— Mautix Lutiiku. XTA8 CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. EARL V A SSOCIA TIONS. I'AGK February 6, 1838—A Schoolmaster Alarmed— "It's a Bad " ' — . I Profession A Curious Coincidence . CHAPTER H. PROBATION. A Spiteful Faii-y—The First Disappointment—Hamlet : An Augury—London at Last ...... 10 CHAPTER HL FIRST SUCCESSES IN LONDON. A Monojjoly of Stage \'illains — Stirring Encouragement — A Momentous Experiment — At the Lyceum — "The " Bells"— Pleasant Prophecies— Charles L"—"Eugene Aram"—A too subtle Richelieu — "Philip"— Hamlet: a Fulfilment— Shakespeare spells Popularity . iS CHAPTER I\". SHAKESPEARE AND TENNYSON. Tradition at Bay — "Queen Mary"—Academic Honours— " " Exit Cibber— The Lyons Mail "— Louis XL"— End of the Bateman Management ..... -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences. -

To Center City: the Evolution of the Neighborhood of the Historicalsociety of Pennsylvania

From "Frontier"to Center City: The Evolution of the Neighborhood of the HistoricalSociety of Pennsylvania THE HISToRICAL SOcIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA found its permanent home at 13th and Locust Streets in Philadelphia nearly 120 years ago. Prior to that time it had found temporary asylum in neighborhoods to the east, most in close proximity to the homes of its members, near landmarks such as the Old State House, and often within the bosom of such venerable organizations as the American Philosophical Society and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. As its collections grew, however, HSP sought ever larger quarters and, inevitably, moved westward.' Its last temporary home was the so-called Picture House on the grounds of the Pennsylvania Hospital in the 800 block of Spruce Street. Constructed in 1816-17 to exhibit Benjamin West's large painting, Christ Healing the Sick, the building was leased to the Society for ten years. The Society needed not only to renovate the building for its own purposes but was required by a city ordinance to modify the existing structure to permit the widening of the street. Research by Jeffrey A. Cohen concludes that the Picture House's Gothic facade was the work of Philadelphia carpenter Samuel Webb. Its pointed windows and crenellations might have seemed appropriate to the Gothic darkness of the West painting, but West himself characterized the building as a "misapplication of Gothic Architecture to a Place where the Refinement of Science is to be inculcated, and which, in my humble opinion ought to have been founded on those dear and self-evident Principles adopted by the Greeks." Though West went so far as to make plans for 'The early history of the Historical Soiety of Pennsylvania is summarized in J.Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, Hisiory ofPhiladelphia; 1609-1884 (2vols., Philadelphia, 1884), 2:1219-22. -

Ruggeri's Amleto

© Luke McKernan 2004 RUGGERO RUGGERI’S AMLETO Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival, University of Notre Dame, South Bend, USA 4 November 2004 Luke McKernan Of all the products of the first thirty years of cinema, when films were silent, perhaps none were so peculiar, so intriguing, and in their way so revealing of the temper of the medium in its formative years, as silent Shakespeare films. Shakespeare in the cinema is enough of a challenge for some people; what about Shakespeare on film when you can’t hear any of the words? The film you are to see this evening is one of two hundred or more Shakespeare films that were made in the silent period of cinema. You are seeing it because it has survived (when so many films from this time have not), because it is a rarity scarcely known even by those who are expert in this area, and because it is a good and interesting film. Not a great film, but arguably the best silent Shakespeare film that exists. It is certainly a film that needs to be much better known. To those who may never have seen a silent film before, be assured that even if you can’t hear the words you will be able to read them, as such films commonly have on-screen titles throughout, and in performance they were never silent as such in any case – for you had music. Silent Shakespeare I said that more than two hundred silent Shakespeare films were made, and that is true, but few of these were feature-length, that is, an hour or more, such as this evening’s attraction. -

APRIL, 1916. SCHOOL LETTER T Is the General

H E PETERITE. VoL. XXI I. APRIL, 1916. No. 222. SCHOOL LETTER T is the general custom of Editors, when writing the School Letter, to commence with the most important event, and this term pride of place must undoubtedly be accorded to the weather. The condition of the weather can be best judged from the fact that to-day is the first fine day we have had since the middle of January, a fact which caused universal acclamation. The activities of the Hockey team have naturally been greatly hampered by the rain, indeed out of 7 matches arranged 4 have had to be cancelled. Out of the three matches played, however, two have been very creditable victories, and, if only the weather clears up, the team should emerge victorious from all the remaining matches. We have received the confident assurances of the Boating authorities that in their sphere of influence the reputation of th School will be worthily maintained, and the information brought in by our spies leads us to the same conclusion. The boater being like ducks, are the only members of the School who have not been inconvenienced by the weather, and so we hope that in the boat-races, maintaining their " duck " reputation, they will simply " fly " to victory. The Corps is still continuing to do good work, although this term reminiscences of parades have been inseparably associ- ated with snow, rain, and mud, especially the latter. A minor 2 SCHOOL LETTER. field-day was held upon Friday, March 17th (an exclusive account of which, written by our special correspondent at the front, appears upon a later page), and the major and combined field- day, is due to take place upon Friday, March 24th.