Alfred and Isabel Bader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aldrichimica Acta Volume 42 No. 1

DEDICATED TO DR. ALFRED BADER ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 85TH BIRTHDAY VOL. 42, NO. 1 • 2009 The Super Silyl Group in Diastereoselective Aldol and Cascade Reactions Iterative Cross-Coupling with MIDA Boronates: towards a General Strategy for Small-Molecule Synthesis Editorial “Please Call Me Alfred” On April 28 of this year, Dr. Alfred Bader, undeniably the world’s Centre of Queen’s University best-known Chemist Collector, celebrated his 85th birthday. Alfred’s in Kingston, Ontario (Canada). amazing life story has been covered extensively in books, magazines, This gift is one of several and lectures, by Alfred himself and by others, and need not be sizeable ones that he has repeated here. Furthermore, most of our readers are undoubtedly made to Queen’s in gratitude aware of Alfred’s strong connections, past and present, not only for the education he received to Sigma-Aldrich, but also to the Aldrichimica Acta, which he has there in the 1940s. showered with his attention for many years. Many of Alfred’s Lesser known, but not paintings have graced the covers of the Acta, including this issue, less important to Alfred, is his which is featuring one of Alfred’s favorite paintings. Bible scholarship, particularly We honor and thank Alfred for his outstanding contributions of Old Testament themes, to Sigma-Aldrich and to the worlds of chemistry, business, and art. which he has studied all his To what he calls the “ABC” (Art, Bible, Chemistry) of his life, one life and taught for a good Photo Courtesy of Alfred Bader should add a “D” for Donating. -

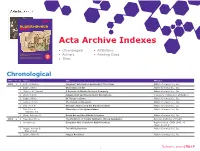

Acta Archive Indexes Directory

VOLUME 50, NO. 1 | 2017 ALDRICHIMICA ACTA Acta Archive Indexes • Chronological • Affiliations 4-Substituted Prolines: Useful Reagents in Enantioselective HIMICA IC R A Synthesis and Conformational Restraints in the Design of D C L T Bioactive Peptidomimetics A A • Authors • Painting Clues Recent Advances in Alkene Metathesis for Natural Product Synthesis—Striking Achievements Resulting from Increased 1 7 9 1 Sophistication in Catalyst Design and Synthesis Strategy 68 20 • Titles The life science business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany operates as MilliporeSigma in the U.S. and Canada. Chronological YEAR Vol. No. Authors Title Affiliation 1968 1 1 Buth, William F. Fragment Information Retrieval of Structures Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1 Bader, Alfred Chemistry and Art Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1 Higbee, W. Edward A Portrait of Aldrich Chemical Company Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 2 West, Robert Squaric Acid and the Aromatic Oxocarbons University of Wisconsin at Madison 2 Bader, Alfred Of Things to Come Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 3 Koppel, Henry The Compleat Chemists Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 3 Biel, John H. Biogenic Amines and the Emotional State Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 4 Biel, John H. Chemistry of the Quinuclidines Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. Warawa, E.J. 4 Clark, Anthony M. Dutch Art and the Aldrich Collection Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1969 2 1 May, Everette L. The Evolution of Totally Synthetic, Strong Analgesics National Institutes of Health 1 Anonymous Computer Aids Search for R&D Chemicals Reprinted from C&EN 1968, 46 (Sept. 2), 26-27 2 Hopps, Harvey B. The Wittig Reaction Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. Biel, John H. -

Professor Dervan's Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Name: Peter B. Dervan Address: Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 tel: 626-395-6002; fax: 626-683-8753; e-mail: [email protected] Education 1967 B.S., Chemistry; Boston College 1972 Ph.D., Chemistry; Yale University Academic Career 1973 NIH Postdoctoral Fellow, Stanford University 1973 Assistant Professor of Chemistry, California Institute of Technology 1979 Associate Professor of Chemistry, California Institute of Technology 1982- Professor of Chemistry, California Institute of Technology 1988- Bren Professor, California Institute of Technology 1994-99 Chair, Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering 2020 Bren Professor of Chemistry, Emeritus Awards 1972 Wolfgang Prize for Distinguished Graduate Studies, Yale University 1977 Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow 1978 Camille and Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar 1983 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellow 1985 ACS Nobel Laureate Signature Award for Graduate Education in Chemistry 1986 Arthur C. Cope Scholar Award, American Chemical Society 1986 Elected member, National Academy of Sciences 1988 Elected member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences 1988 Harrison Howe Award, American Chemical Society, Rochester Section 1993 Arthur C. Cope Award, American Chemical Society 1993 Willard Gibbs Medal, American Chemical Society, Chicago Section 1994 Nichols Medal, American Chemical Society, New York Section 1996 Maison de la Chimie Foundation Prize, France 1997 Elected member, National Academy of Medicine 1998 Remsen Award, American Chemical Society, Baltimore Section 1998 Kirkwood Medal, American Chemical Society, New Haven Section 1999 Alfred Bader Award, American Chemical Society 1999 Max Tishler Prize, Harvard University 1999 Linus Pauling Medal, American Chemical Society, Oregon Portland Puget Sound Section 1999 Richard C. -

Curriculum Vitae - Victor Algirdas Snieckus

HETEROCYCLES, Vol. 88, No. 1, 2014 5 HETEROCYCLES, Vol. 88, No. 1, 2014, pp. 5 - 43. © 2014 The Japan Institute of Heterocyclic Chemistry DOI: 10.3987/COM-13-S(S)CV CURRICULUM VITAE - VICTOR ALGIRDAS SNIECKUS Queen's University Department of Chemistry Tel: (613) 533-2239 Kingston, Ontario K7L 3N6 Fax: (613) 533-6089 E-mail: [email protected] PERSONAL DATA Born Kaunas, Lithuania, 1 August, 1937 Citizenship Canadian Married Anne Cecilia (Pinkham) Snieckus Two Children Darius Victor (b. 1967) Naomi Marie (b. 1970) Languages English, French, German, Lithuanian, Estonian Outside Interests History of Science, Jazz, Table Tennis EDUCATION Preuniversity Germany, 1945-48 Alberta, Canada, 1948-55 B.Sc. (Honors) University of Alberta, 1959 M.Sc. University of California, Berkeley, 1961 (with D.S. Noyce) Ph.D. University of Oregon, 1965 (with V. Boekelheide) Postdoctoral National Research Council, Ottawa, 1965-66 (with O.E. Edwards) ACADEMIC POSITIONS University of Waterloo Assistant Professor 1967-71 Associate Professor 1971-79 Professor 1979-92 Monsanto/NSERC Ind Res Chair 1992-98 Queen’s University Bader Chair in Organic Chemistry 1998- Bader Chair in Organic Chemistry Emeritus 2009- Brock University Adjunct Professor, Organic Chemistry 2009- Snieckus Innovations Director 2009- RESEARCH INTERESTS The Snieckus group has contributed to the development and application of the directed ortho metalation reaction (DoM) and used it as a conceptual platform for discovery of new efficient methods for the 6 HETEROCYCLES, Vol. 88, No. 1, 2014 regioselective synthesis of polysubstituted aromatics and heteroaromatics. The directed remote metalation (DreM) reaction and DoM – linked transition metal catalyzed cross coupling (especially Suzuki-Miyaura) were first uncovered in his laboratories. -

Aldrichimica Acta 33, 2000

SERVING THE SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITY FOR OVER 3O YEARS AldrichimAldrichimicaica AACTACTA VOL.33, NO.1 • 2000 The Chemical Vapor Deposition of Metal Nitride Films Using Modern Metalorganic Precursors Synthetic Applications of Indium Trichloride Catalyzed Reactions Purpald®: A Reagent That Turns Aldehydes Purple! CHEMISTS HELPING CHEMISTS NewNew ProductsProducts The tert-butyldimethylsilyl analog of OMe O O O Danishefsky’s diene is now available. It has been used to prepare a variety of OTBDMS OTBDMS OTBDMS 52,599-5 52,490-5 52,613-4 bicyclic enones and 2,3-dihydro-4H- TBDMSO pyran-4-ones.1-3 A variety of nucleophiles have been used to open the oxirane (1) Uchida, H. et al. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 113. (2) Pudukulathan, Z. et al. J. Am. ring of these compounds. Examples include lithium Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 11953. (3) Annunziata, R. et al. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 3605. acetylides1,2 and lithium dithianes.3 51,536-1 trans-3-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyloxy)-1-methoxy-1,3- (1) Arista, L. et al. Heterocycles 1998, 48, 1325. (2) Maguire, R. J. et al. J. Chem. Soc., butadiene, 95% Perkin Trans. 1 1998, 2853. (3) Smith, A. B., III; Boldi, A. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 6925. Building blocks for trans-2- 52,599-5 tert-Butyldimethylsilyl (R)-(+)-glycidyl ether, 98% methyl-6-substituted piperidines 52,490-5 tert-Butyldimethylsilyl (S)-(–)-glycidyl ether, 98% via deprotonation with sec-butyl- N N H lithium followed by reaction with Boc 52,613-4 tert-Butyldimethylsilyl glycidyl ether, 98% an electrophile.1-3 52,288-0 52,290-2 (1) Chackalamannil, S. -

Aldrichimica Acta 34, 2001

1951–2001: FIFTY YEARS OF CHEMISTS HELPING CHEMISTS AldrichimicaAldrichimica AACTACTA VOL.34, NO.1 • 2001 Preparation of Optically Active α-Amino Acids Alkoxymethylenemalonates in Organic Synthesis CHEMISTS HELPING CHEMISTS 53,182-0 N,N’-Di-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)thiourea, 97% 54,548-1 (1R,2S)-1-Phenyl-2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-propanol, 98% 54,897-9 (1S,2R)-1-Phenyl-2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-propanol, 98% O S O This diprotected thiourea is widely used in the synthesis of heterocycles, including a ONN O H H pentacyclic guanidine system as an These norephedrine derivatives are intermediate to ptilomycalin A,1 and, recently, HO N HO N useful chiral mediators and have in the preparation of p-N,N’-bis-Boc-guanidophenol, a key intermediate for the applications in the enantioselective preparation of a series of aryl o-aroylbenzoates as serine protease inhibitors.2 CH3 CH3 addition of acetylides to carbonyl (1) Nagasawa, K. et al. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 187. (2) Jones, P.B.; Porter, N.A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. compounds. Examples include the 54,548-1 54,897-9 1999, 121, 2753. synthesis of the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitor DMP 2661 and the enantioselective addition of diethylzinc to aldehydes.2 54,036-6 1,1-Diethoxy-3-methyl-2-butene, 97% (1) Pierce, M.E. et al. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 8536. (2) Soai, K. et al. ibid. 1991, 56, 4264. OEt This acetal has been utilized in the synthesis of the related 1-alkoxy-3-phenylselenoalkenes and 3-phenylselenoalkanals,1 OEt and in the preparation of 2,2-dimethylchromenes from 54,174-5 Tri-O-acetyl-β-D-arabinosylbromide, 95% electron-deficient phenols.2 (1) Nishiyama, Y. -

Aldrichimica Acta

VOLUME 52, NO. 1 | 2019 ALDRICHIMICA ACTA Dr. Alfred Bader 1924–2018 Remembering Dr. Alfred R. Bader (1924–2018) Phenothiazines, Dihydrophenazines, and Phenoxazines: Sustainable Alternatives to Precious-Metal-Based Photoredox Catalysts Titanium Salalen Catalysts for the Asymmetric Epoxidation of Terminal (and Other Unactivated) Olefins with Hydrogen Peroxide The life science business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany operates as MilliporeSigma in the U.S. and Canada. RememberinG Dr. Alfred Bader Alfred Bader, a pioneer in the field of chemistry and co-founder of Aldrich Chemical Company, now a part of the Life Science business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, passed away on December 23, 2018, at the age of 94. Scientists from around the world grew up using Aldrich Chemical products in their labs, referencing the Aldrich Catalog and Handbook, and appreciating the oft-used request to “Please Bother Us.”— a request for customers to call at any time with any question or idea. Bader’s commitment to his customers and to the broader scientific community could be felt in all aspects of his work. Bader’s remarkable story began in 1938, when at age 14, he fled his native Vienna during the rise of Nazism. He would eventually complete a chemistry degree at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, and later a Ph.D. in organic chemistry at Harvard. Bader was an entrepreneur at heart. He began his career in 1950 working as a chemist for the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company in Milwaukee. A year later, he and Jack Eisendrath founded Aldrich Chemical Company, which would eventually grow to become one of the largest chemical companies in the world. -

Johnson Matthey Technology Review

ISSN 2056-5135 JOHNSON MATTHEY TECHNOLOGY REVIEW Johnson Matthey’s international journal of research exploring science and technology in industrial applications Volume 60, Issue 2, April 2016 Published by Johnson Matthey www.technology.matthey.com © Copyright 2016 Johnson Matthey Johnson Matthey Technology Review is published by Johnson Matthey Plc. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. You may share, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format for any lawful purpose. You must give appropriate credit to the author and publisher. You may not use the material for commercial purposes without prior permission. You may not distribute modifi ed material without prior permission. The rights of users under exceptions and limitations, such as fair use and fair dealing, are not affected by the CC licenses. www.technology.matthey.com JOHNSON MATTHEY TECHNOLOGY REVIEW www.technology.matthey.com Johnson Matthey’s international journal of research exploring science and technology in industrial applications Contents Volume 60, Issue 2, April 2016 88 Guest Editorial: The Importance of Characterisation Techniques By Peter Ash 90 Surface Selective 1H and 27Al MAS NMR Observations of Strontium Oxide Doped γ-Alumina By Nathan S. Barrow, Andrew Scullard and Nicola Collis 98 Erratum: The Effects of Hot Isostatic Pressing of Platinum Alloy Castings on Mechanical Properties and Microstructures By Teresa Fryé 99 “New Trends in Cross-Coupling: Theory and Applications” A book review by Victor Snieckus 106 Frontiers in Environmental Catalysis A conference review by Djamela Bounechada 110 7th International Gold Conference A conference review by Nicoleta Muresan and Agnes Raj 117 The Use of Annular Dark-Field Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy for Quantitative Characterisation By Katherine E.