Tevye's Daughters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Essay for “Tevye”

Tevye By J. Hoberman In summer 1939, actor-director Maurice Schwartz began work on his long-delayed “Tevye,” the film he first proposed in 1936 and had publicly announced in January 1938. Schwartz, who based his film on the stories of leading Yiddish author and playwright Sholom Aleichem, created and starred in a stage play of “Tevye” twenty years before. A $70,000 ex- travaganza, the film was produced by Harry Ziskin, co-owner of the largest kosher restaurant in the Times Square area. After three weeks of rehearsal on the stage of the Yiddish Art Theater, shooting began on a 130-acre potato farm near Jericho, Long Island. On August 23, midway through the shoot, Hitler seized Danzig. A Nazi invasion of Poland seemed imminent. Political tensions and the deterioration of the Euro- pean situation were felt on the set of “Tevye.” Many Maurice Schwartz as Tevye the Dairyman. of those involved in the production had family in Poland; some were anxious to return. Actor Leon contrast, “Fiddler on the Roof,” filmed by Norman Liebgold booked passage on a boat leaving for Jewison in 1973, emphasizes the generational gap Poland on August 31. But “Tevye” had fallen behind between Tevye and his daughters and ends with schedule – a number of scenes had been ruined Khave and her Gentile husband leaving for America due to the location’s proximity to Mitchell Airfield. along with Tevye. Although his visa had expired, Liebgold was com- pelled to postpone his departure. The next day, On one hand, Schwartz’s “Tevye” stands apart from the Nazis invaded Poland. -

Course Submission Form

Course Submission Form Instructions: All courses submitted for the Common Core must be liberal arts courses. Courses may be submitted for only one area of the Common Core. All courses must be 3 credits/3 hours unless the college is seeking a waiver for a 4-credit Math or Science course (after having secured approval for sufficient 3-credit/3-hour Math and Science courses). All standard governance procedures for course approval remain in place. College Kingsborough Community College Course Number Yiddish 30 Course Title Yiddish Literature in Translation l Department(s) Foreign Languages Discipline Language and Literature Subject Area Enter one Subject Area from the attached list. Yiddish Credits 3 Contact Hours 3 Pre-requisites English 12 Mode of Instruction Select only one: x In-person Hybrid Fully on-line Course Attribute Select from the following: Freshman Seminar Honors College Quantitative Reasoning Writing Intensive X Other (specify): Liberal Arts/ Gen Ed Catalogue Designed for non-Yiddish speaking students, course consideration is on the emergence of Yiddish writers in the Description modern world. Emphasis is on the main literary personalities and their major contributions. All readings and discussions in English. Syllabus Syllabus must be included with submission, 5 pages max Waivers for 4-credit Math and Science Courses All Common Core courses must be 3 credits and 3 hours. Waivers for 4-credit courses will only be accepted in the required areas of Mathematical and Quantitative Reasoning and Life and Physical Sciences. Such waivers will only be approved after a sufficient number of 3-credit/3-hour math and science courses are approved for these areas. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 11, 2015

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 11, 2015 CONTACT: Meg Walker Gretchen Koss President, Dir. of Marketing President, Dir. of Publicity Tandem Literary Tandem Literary 212-629-1990 ext. 2 212-629-1990 ext. 1 [email protected] [email protected] 20th Annual Audie® finalists announced in thirty categories Winners announced at the Audie Awards Gala in New York City on May 28th hosted by award winning author Jack Gantos Philadelphia, PA – The Audio Publishers Association (APA) has announced finalists for its 2015 Audie Awards® competition, the only awards program in the United States devoted entirely to honoring spoken word entertainment. Winners will be announced at the Audies Gala on May 28, 2015, at the New York Academy of Medicine in New York. Newbery award winning author, and audiobook narrator extraordinaire, Jack Gantos will emcee the event and says "I'm thrilled to host the Audies. Unlike when I'm in the recording studio, while on stage at the Audies Gala I can wear a watch, have my stomach growl, jiggle pocket change, trip over my own tongue, laugh at my own jokes, completely screw up my lines and not have to worry about repeating myself-- again and again. It is an honor to be a part of recognizing all the incredible audio talent in the industry who do the hard work of controlling themselves in the studio every single day." This year there will be an additional category: JUDGES AWARD – SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY. Janet Benson, Audies Competition Chair, says “Recognizing the constantly evolving nature of modern science and technology, the Audies Competition Committee wished to honor audiobooks which celebrate Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. -

Fiddler on the Roof’

Solihull School Presents 20th - 24th March 2012 Bushell Hall After Tevye leaves, Perchik rejoices his good fortune, admitting to Hodel, “Now I Have Everything.” Confused by the changes taking place in his world, Tevye for the fi rst time asks Golde “Do You Love Me?” Eventually, Hodel’s strong love for Perchik compels her to leave her family and travel “Far from the Home I Love” in order to be with her beloved in Siberia. Chava, the third daughter, secretly begins to see a young Russian gentile, Fyedka. Although Tevye has weathered the unexpected courtships of Tzeitel and Hodel with dignity, he is unable to tolerate this further and more radical defi ance of tradition. Chava’s contemplation of marrying outside of the Jewish faith is a violation of his religious beliefs, and Tevye vehemently forbids her to continue the relationship with Fyedka. When she persists, Tevye, who can bend no farther, banishes her from the family, refusing to acknowledge Chava as his daughter. By this time, the Tsar has ordered that all Jews evacuate their homes, and the village reluctantly begins to pack their belongings. Knowing that she may never see her parents and sisters again, Chava returns briefl y for a fi nal reconciliation, SYNOPSIS explaining that Fyedka and she are also moving away from Anatevka because they cannot remain amongst people who treat others with such callousness. The place is Anatevka, a village in Tsarist Russia. The time is 1905, the eve of the revolution. The musical opens with the Although Golde cannot challenge her husband’s edict to ignore Chava’s overtures, Tzeitel consoles her younger sister by pulling haunting strains of a fi ddler perched precariously on a roof. -

|||GET||| Tevye the Dairyman and Motl the Cantors Son 1St Edition

TEVYE THE DAIRYMAN AND MOTL THE CANTORS SON 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Sholem Aleichem | 9780143105602 | | | | | Tevye Dairyman For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world. Seller Image. More information about this seller Contact this seller 4. Contains some markings such as highlighting and writing. Sholom Aleichem. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. Seller Rating:. His silliness comes across on the screen in other ways - he tries to assert his dictatorial authority to little effect, and on one occasion looks like a toddler having a tantrum instead. Tevye is a stubborn curmudgeon in many ways who will not see his part in his own undoings and yet he evokes sympathy due to his general good outlook, albeit tinged with a la I thoroughly enjoyed this satirical voyage through the lives of two slightly exaggerated Jewish males. Book category Adult Fiction. About this product. This Sholom Aleichem is amazing -- I've read two of his books in the last couple of months and I laughed and cried and learned so much from each of them. Another of the less pleasant, yet historically interesting, notable features of Motl was child characters learning sexism from adults via cumulative remarks. The guy runs a dairy, after all. Condition: acceptable. Tevye is the lovable, Bible-quoting father of seven daughters, a modern Job whose wisdom, humor, and resilience inspired the lead character in Fiddler on the Roof. In exchange, this guy tutors Tevye's daughters. Pickup not available. Once I'd seen too many pictures Tevye the Dairyman and Motl the Cantors Son 1st edition heaps of dead people's glasses and shoes and they ceased to have an impact. -

Tevye the Dairyman a GREAT JEWISH BOOKS TEACHER WORKSHOP RESOURCE KIT

Tevye the Dairyman A GREAT JEWISH BOOKS TEACHER WORKSHOP RESOURCE KIT Teachers’ Guide This guide accompanies resources that can be found at: http://teachgreatjewishbooks.org/resource-kits/tevye-dairyman. Introduction Sholem Aleichem, the pseudonym of Sholem Rabinovitch (1859-1916), was one of the greatest Jewish writers of modern times, a pioneer of literary fiction in Yiddish who transformed the folk materials and experiences of Eastern European Jews into classics of world literature. His most beloved character, Tevye the Dairyman, became the protagonist of stage and film adaptations, including the Broadway musical and film Fiddler on the Roof, securing his place in popular culture worldwide; even before that, though, Sholem Aleichem's stories featuring Tevye were appreciated as brilliant comic distillations of modern Jewish experience. This kit provides resources with which teachers can introduce their students to the character of Tevye and to the choices that have been made in presenting and performing this character over the years. Subjects Eastern Europe, Fiction, Film, Performance, Yiddish Reading and Background: Several translations of Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye stories are available in paperback, suitably priced for teaching; these include Hillel Halkin’s in Tevye the Dairyman and the Railroad Stories (1987) and Aliza Shevrin’s in Tevye the Dairyman and Motl the Cantor’s Son (2009). A short biographical article on Sholem Aleichem can be found in the YIVO Encyclopedia, while Jeremy Dauber’s The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem (2013) presents a full, appropriately page-turning treatment of the writer’s life and legacy. Alisa Solomon’s Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof (2013) offers a robust, wide-ranging survey of the creation of the musical and its worldwide influence. -

Who's Who in the Cast

WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST ROBERT PETKOFF (Bruce). Broadway: All The Way with Bryan Cranston, Anything Goes, Ragtime, Spamalot, Fiddler On The Roof and Epic Proportions. London: The Royal Family with Dame Judi Dench and Tantalus. Regional: Sweeney Todd, Hamlet, Troilus & Cressida, Follies, Romeo & Juliet, Compleat Female Stage Beauty and The Importance Of Being Earnest. Film: Irrational Man, Vice Versa, Milk and Money, Gameday. TV: Elementary, Forever, Law and Order: SVU, The Good Wife and more. Robert is an award-winning audiobook narrator. SUSAN MONIZ (Helen). Broadway: Grease – Sandy & Rizzo. Regional: Follies – Sally (Chicago Shakespeare Theater); October Sky –Elsie (world premier); Peggy Sue Got Married – Peggy (world premier); Kismet (Joseph Jefferson award); Into the Woods, 9 to 5, Carousel, (Marriott Theatre); The Merry Widow, The Sound Of Music, (Chicago Lyric Opera); Hot Mikado (Ford’s Theatre); Phantom, Chitty- Chitty Bang-Bang (Fulton Theatre); Shadowlands, The Spitfire Grill, (Provision Theatre); Evita, BIG, (Drury Lane Theatre). TV: Chicago PD; Romance, Romance (A&E). KATE SHINDLE (Alison). Broadway: Legally Blonde (Vivienne), Cabaret (Sally Bowles), Wonderland (Hatter), Jekyll & Hyde. Elsewhere: Rapture, Blister, Burn (Catherine), After the Fall (Maggie), Restoration, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Gypsy, Into the Woods, The Last Five Years, First Lady Suite, The Mousetrap. Film/TV: Lucky Stiff, SVU, White Collar, Gossip Girl, The Stepford Wives, Capote. Kate is a longtime activist, author of Being Miss America: Behind the Rhinestone Curtain and President of Actors’ Equity Association. twitter.com/AEApresident ABBY CORRIGAN (Middle Alison). Stage: Cabaret, A Chorus Line (TCS); Shrek (Blumey award), In The Heights, Peter Pan, Rent (NWSA); Next to Normal (QCTC); Film/TV: Headed South For Christmas (Painted Horse), A Smile As Big As The Moon (Hallmark), Homeland (HBO), Rectify (Sundance), Banshee (Cinemax). -

Fiddler on the Roof Department of Theatre, Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons Department of Theatre Production Programs Department of Theatre Fall 1996 Fiddler on the Roof Department of Theatre, Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/theatre_programs Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Department of Theatre, Florida International University, "Fiddler on the Roof" (1996). Department of Theatre Production Programs. 3. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/theatre_programs/3 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theatre at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Theatre Production Programs by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thefaculty and staff of theDepartment ofTheatre and Dance would like to welcomeyou to this productionof Fiddleron the Roof Theopening of the Herbert and Nicole Wertheim Performing ArtsCenter is theculmination of a long-helddream. Since FIU's opening in 1972, we have beenpresenting our productions in spacesnot designed to betheatres. While what we hope havebeen enjoyable evenings of theatrein VH100 and OM 150 , workin thesespaces has alwayspresented us with challenges.While the challengeshave been stimulating to our imaginations, wehave longed for a "real"theatre. Nowour dreams are realized; two beautiful , well-equippedperforming spaces. And for our audience,a wonderful environment in which to viewtheatre. We expect the new facilities will stimulateus to higherlevels of theatreperformance. We welcome you to join with us in enjoyingthe benefits of our newhome. We hope you enjoy tonight's performance and are ableto join usfor the other great shows this Season! TheraldTodd Chairperson, Departmentof Theatre and Dance FIU THEATRE PRESENTS basedon SholemAleichem stories by specialpermission of ArnoldPerl Bookby JOSEPHSTEIN Music by JERRYBOCK Lyricsby SHELDONHARNICK OriginalDirection Reproduced by PhillipM. -

A Hundred Years Since Sholem Aleichem's Demise Ephraim Nissan

Nissan, “Post Script: A Hundred Years Since Sholem Aleichem’s Demise” | 116 Post Script: A Hundred Years since Sholem Aleichem’s Demise Ephraim Nissan London The year 2016 was the centennial year of the death of the Yiddish greatest humorist. Figure 1. Sholem Aleichem.1 The Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem (1859–1916, by his Russian or Ukrainian name in real life, Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich or Sholom Nokhumovich Rabinovich) is easily the best-known Jewish humorist whose characters are Jewish, and the setting of whose works is mostly in a Jewish community. “The musical Fiddler on the Roof, based on his stories about Tevye the Dairyman, was the first commercially successful English-language stage production about Jewish life in Eastern Europe”. “Sholem Aleichem’s first venture into writing was an alphabetic glossary of the epithets used by his stepmother”: these Yiddish 1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sholem_Aleichem.jpg International Studies in Humour, 6(1), 2017 116 Nissan, “Post Script: A Hundred Years Since Sholem Aleichem’s Demise” | 117 epithets are colourful, and afforded by the sociolinguistics of the language. “Early critics focused on the cheerfulness of the characters, interpreted as a way of coping with adversity. Later critics saw a tragic side in his writing”.2 “When Twain heard of the writer called ‘the Jewish Mark Twain’, he replied ‘please tell him that I am the American Sholem Aleichem’”. Sholem Aleichem’s “funeral was one of the largest in New York City history, with an estimated 100,000 mourners”. There exists a university named after Sholem Aleichem, in Siberia near China’s border;3 moreover, on the planet Mercury there is a crater named Sholem Aleichem, after the Yiddish writer.4 Lis (1988) is Sholem Aleichem’s “life in pictures”. -

Danny Daniels: a Life of Dance and Choreography

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2003 Danny Daniels: A life of dance and choreography Louis Eric Fossum Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Fossum, Louis Eric, "Danny Daniels: A life of dance and choreography" (2003). Theses Digitization Project. 2357. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2357 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DANNY DANIELS: A LIFE OF DANCE AND CHOREOGRAPHY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies: Theatre 'Arts and Communication Studies by Louis Eric Fossum June 2003 DANNY DANIELS: A LIFE OF DANCE AND CHOREOGRAPHY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Louis Eric Fossum June 2003 Approved by: Processor Kathryn Ervin, Advisor Department of Thea/fer Arts Department of Theater Arts Dr. Robin Larsen Department of Communications Studies ABSTRACT The career of Danny Daniels was significant for its contribution to dance choreography for the stage and screen, and his development of concept choreography. Danny' s dedication to the art of dance, and the integrity of the artistic process was matched by his support and love for the dancers who performed his choreographic works. -

Lesbian Suicide Musical"

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadt.commons.gc.cuny.edu Branding Bechdel’s Fun Home: Activism and the Advertising of a "Lesbian Suicide Musical" by Maureen McDonnell The Journal of American Drama and Theatre Volume 31, Number 2 (Winter 2019) ISNN 2376-4236 ©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Alison Bechdel offered a complicated and compelling memoir in her graphic novel Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (2006), adapted by Lisa Kron and Jeanine Tesori into the Broadway musical Fun Home (2015). Both works presented an adult Bechdel reflecting on her father’s troubled life as a closeted gay man and his possible death by suicide. As Bechdel herself noted, “it’s not like a happy story, it’s not something that you would celebrate or be proud of.”[1] Bechdel’s coining of “tragicomic” as her book’s genre highlights its fraught narrative and its visual format indebted to “comics” rather than to comedy. Bechdel’s bleak overview of her father’s life and death served as a backdrop for a production that posited truthfulness as life-affirming and as a means of survival. Fun Home’s marketers, however, imagined that being forthright about the production’s contents and its masculine lesbian protagonist would threaten the show’s entertainment and economic potential. It was noted before the show opened that “the promotional text for the show downplays the queer aspects,” a restriction that was by design.[2] According to Tom Greenwald, Fun Home’s chief marketing strategist and the production’s strategy officer, the main advertising objective was to “make sure that it’s never ever associated specifically with the ‘plot or subject matter.’” Instead, the marketing team decided to frame the musical as a relatable story of a family “like yours.” [3] The marketers assumed that would-be playgoers would be uninterested in this tragic hero/ine if her sexuality were known. -

2015/16 Annual Report

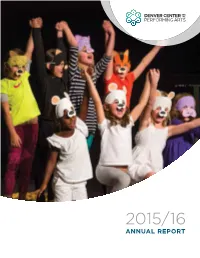

2015/16 ANNUAL REPORT 2015/16 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2015/16 Daniel L. Ritchie, Chairman & CEO William Dean Singleton, Secrectary/Treasurer IMPACT Robert Slosky, First Vice Chair Margot Gilbert Frank, Second Vice Chair Dr. Patricia Baca Joy S. Burns Isabelle Clark Navin Dimond L. Roger Hutson Mary Pat Link David Miller Robert C. Newman Hassan Salem Richard M. Sapkin Martin Semple 1,224,554 Tara Smith Jim Steinberg GUESTS Ken Tuchman ANNUAL INCREASE OF 32% Tina Walls Lester L. Ward Dr. Reginald L. Washington Judi Wolf Sylvia Young GROWTH IN ENGAGEMENT 2015/16 HONORARY TRUSTEES FY2016 VS FY2015 Jeannie Fuller M. Ann Padilla Cleo Parker Robinson 2015/16 HELEN G. BONFILS FOUNDATION 82% +57% BOARD OF TRUSTEES TOTAL PAID CAPACITY OFF-CENTER ATTENDANCE Martin Semple, President BEST EVER 14,149 Jim Steinberg, Vice President Judi Wolf, Secrectary/Treasurer Lester L. Ward, President Emeritus David Miller +11% +1,426% Daniel L. Ritchie BROADWAY SHAKESPEARE IN THE PARKING William Dean Singleton SUBSCRIBED SEATS LOT PARTICIPATION Robert Slosky Dr. Reginald L. Washington 83,255 9,158 2015/16 EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT Scott Shiller, President & CEO (through May 2016) +514% +21% Clay Courter, Vice President, DPS SHAKESPEARE COLORADO NEW PLAY SUMMIT Facilities & Event Services FESTIVAL WORKSHOPS PAID ATTENDANCE John Ekeberg, Executive Director, SERVED 3,381 1,661 Broadway Vicky Miles, Chief Financial Officer Jennifer Nealson, Chief Marketing Officer Kent Thompson, Producing Artistic Director, +26% +18% Theatre Company Charles Varin, Managing Director, EDUCATION PARTICIPATION EVENT SERVICES Theatre Company 105,908 HOSTED EVENTS David Zupancic, Director of Donor 291 Development Trustees & management as of June 30, 2016 $150,000,000 ECONOMIC IMPACT* Cover: DCPA Education’s Musical Mayhem Summer 2 Performance *3.5 x $1 in ticket sales Photo by Adams VisCom CHAIRMAN’S LETTER By nearly all accounts, fiscal year 2016 was one for the record books.