The Fisher Effect and the Financial Crisis of 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deflation and the Fisher Equation

Economic SYNOPSES short essays and reports on the economic issues of the day 2010 ■ Number 27 Deflation and the Fisher Equation William T. Gavin, Vice President and Economist rving Fisher (1867-1947), one of America’s greatest federal funds rate was 2.18 percent and, in the 1980s, it I monetary economists, is famous for many reasons. was a whopping 4.61 percent. One of the most important is the Fisher equation, which states that the nominal interest rate is equal to the real interest rate plus the expected inflation rate. This is a So, according to Irving Fisher, statement about equilibrium in the market for bonds, not one reason to worry about deflation is about the factors that determine these two components. that the federal funds rate is expected Depending on which market rate is used, the expected real return will include a premium for various sources of to be held near zero as the economy risk. For most of post-WWII U.S. history, estimates of this grows out of this recession. risk premium in the federal funds market have been small relative to estimates of the risk-free real interest rate and the expected inflation rate, so they are ignored in this essay. With the federal funds rate near zero since December The chart shows the Fed’s policy rate—the federal funds 2008 and expected to remain there for the next year or two, rate—and the consumer price index (CPI) inflation trend. the Fisher equation has important implications for the The trend is measured as a 25-month centered moving expected inflation rate. -

On the Fisher Effect: a Review

Munich Personal RePEc Archive On The Fisher Effect: A Review Bosupeng, Mpho University of Botswana 2016 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/77916/ MPRA Paper No. 77916, posted 27 Mar 2017 14:07 UTC On The Fisher Effect: A Review Author Name: Mpho Bosupeng On The Fisher Effect: A Review Abstract The Fisher effect proposes that in the long run, nominal interest rates trend positively with inflation. In numerous studies the long run Fisher effect has been proved several times as compared to the short run Fisher effect phenomenon. The reason is in the long run, interest rates exhibit minimum volatility therefore resulting in the long run association. Even though the literature has been impressive in terms of validating the hypothesis, many central banks and policy makers have been lost in the lurch regarding the overall standpoint of the Fisher parity. This paper reviews the Fisher effect and examines factors that impinge on the hypothesis namely: inflation targeting, data set range and the regulation of the financial system. JEL: E43 KEYWORDS: Fisher effect; interest rates; inflation Introduction The Fisher effect is an equilibrium relation every central bank values and appreciates. The theory postulates that nominal interest rates rise together with inflation in the long run while real interest rates remain indifferent to this transaction following Fisher (1930). Many central banks securities such as certificates and bonds usually have fixed real interest rates. In practical terms, real interests are not always stagnant. In effect, the direct relationship between nominal interest rates and inflation changes over time which impinges on the Fisher effect. -

Testing the Fisher Hypothesis in the Presence of Structural Breaks and Adaptive Inflationary Expectations: Evidence from Nigeria

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Uyaebo, Stephen O. U. et al. Article Testing the Fisher hypothesis in the presence of structural breaks and adaptive inflationary expectations: Evidence from Nigeria CBN Journal of Applied Statistics Provided in Cooperation with: The Central Bank of Nigeria, Abuja Suggested Citation: Uyaebo, Stephen O. U. et al. (2016) : Testing the Fisher hypothesis in the presence of structural breaks and adaptive inflationary expectations: Evidence from Nigeria, CBN Journal of Applied Statistics, ISSN 2476-8472, The Central Bank of Nigeria, Abuja, Vol. 07, Iss. 1, pp. 333-358 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/191679 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

A Lower Bound on Real Interest Rates by Jesse Aaron Zinn

Real Interest Rate in Developed Economies Median and Range Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco See the note at the end of article. A Lower Bound on Real Interest Rates By Jesse Aaron Zinn Peer Reviewed 1 Jesse Aaron Zinn is an Assistant Professor of Economics in the College of Business at Clayton State University. His research interests include macroeconomics, public finance, and developmental economics. He earned his PhD in Economics at University of California, Santa Barbara. Abstract In this short article, the author demonstrates that real interest rates cannot be lower than -1 (i.e. -100%). He discusses how the textbook approximation to the Fisher equation can lead to the erroneous belief that there is no lower bound on real interest rates. He also speculates that the widespread use of the Fisher equation is why we had yet to realize that a lower bound on real rates exists. This leads him to advocate using and teaching the exact Fisher equation, rather than its approximation. Introduction Negative real interest rates have been common in the United States and other countries since the financial crisis of 2007-8. In fact, Japan has often had negative real interest rates going back to the early 1990s. In some countries, such as Denmark and Switzerland, there have been cases where nominal interest rates have also turned negative, disproving the idea that zero is an impenetrable lower bound on nominal rates. These phenomena have, no doubt, lead many to wonder how low rates can go. The objective of this short piece is to demonstrate the existence of a lower bound on real rates of interest. -

Real Interest Rate and Fisher Equation

6. Real interest rate, Fisher equation, Fisher effect 1. Real interest rate The real interest rate of an economy represents the purchasing power of the economy’s nominal interest rate : it is the nominal rate expressed in terms of goods. That the nominal interest rate between period and period 1 is means that, by lending 1 currency unit in , one gets 1 currency units in 1. That the real interest rate between period and period 1 is means that, by lending 1 unit of goods int , one gets 1 units of goods in 1. Thus, expresses purchasing power: the amount of goods obtained from each unit of good lent. 2. An example on the real interest rate Let “goods” be represented by the CPI basket. There are two periods, 1 and 2. The nominal interest rate between 1 and 2 is 10%. The cost of the CPI basket in 1 is 204 EUR. The cost of the CPI basket in 2 is 220 EUR; see the sketch on the right. With this information, the CPI inflation rate is 220 204 7.84%. 204 If 612 EUR are lent in 1. Then 612 1 612 1 0.10 673.2 EUR are obtained in 2. In 1, the purchasing power of 612 EUR is 612/ 612/204 3 baskets. In 2, the purchasing power of 673.2 EUR is 673.2/ 673.2/220 3.06 baskets. The real interest rate measures the change in purchasing power of the money lent. Specifically, transforms 3 baskets into 3.06 baskets. Thus, satisfies 3 1 3.06, so 0.02 2%. -

IRVING FISHER – Forerunner of Monetarism

PROFILES OF WORLD ECONOMISTS IRVING FISHER – forerunner of monetarism doc. Ing. Ján Iša, DrSc. Irving Fisher (1867 to 1947), who the theory of capital and interest, the theo- J. A. Schumpeter labelled as the greatest ry of index numbers and accounting, the theoretical economist of America, signifi- ”Phillips curve” and economic research cantly contributed to numerous spheres of methodology. economic theory and statistics. Perhaps he Fisher was the first American mathemati- is most known for his contribution to the de- cal economist, entrepreneur, reformer and velopment of the modern quantity theory, lecturer. Irving Fisher was born on 27th February, 1867 in Saugerti- He was appointed a full professor of economics in 1898 and es (New York) and lived in New Haven (Connecticut). Over ti- worked at Yale University actively up until 1920, afterwards me Fisher attended gradually schools in Peace Dale (Rhode Is- devoting his time mainly to writing books (of his 28 books pub- land), New Haven (Connecticut) and Saint Louis (Missouri). lished 18 dealt with economic theory) and a number of various Just at the time when he had finished secondary school and ga- activities outside the university. He taught only on a part-time ined a place at Yale College, his father died, leaving Irving 500 basis and therefore had less of an influence on students and, in dollars for his college education. contrast to other eminent architects of economic science (for At Yale University he studied mathematics, science, sociolo- example J. M. Keynes); he did not create a distinctive economic gy and philosophy. His most eminent teachers were the mathe- school. -

Nber Working Paper Series Searching for Irving Fisher

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES SEARCHING FOR IRVING FISHER Kris James Mitchener Marc D. Weidenmier Working Paper 15670 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15670 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2010 We thank Michael Bordo, Richard Burdekin, Andy Rose, Eric Swanson, and participants at UC Berkeley, the San Francisco Fed, and the ASSA meetings for comments and suggestions. Mitchener acknowledges the generous financial support of the Hoover Institution while in residence as the W. Glenn Campbell and Rita Ricardo-Campbell National Fellow. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by Kris James Mitchener and Marc D. Weidenmier. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Searching for Irving Fisher Kris James Mitchener and Marc D. Weidenmier NBER Working Paper No. 15670 January 2010 JEL No. E4,G1,N2 ABSTRACT There is a long-standing debate as to whether the Fisher effect operated during the classical gold standard period. We break new ground on this question by developing a market-based measure of general inflation expectations during the gold standard. Since the gold-silver price ratio was widely used to track inflation during the gold standard period, we are able to derive a measure of inflation expectations using the interest-rate differential between Austrian silver and gold perpetuity bonds with identical terms. -

Threshold Cointegration Test of the Fisher Effect Biyong Xu Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2004 Threshold cointegration test of the Fisher effect Biyong Xu Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Finance Commons, and the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Xu, Biyong, "Threshold cointegration test of the Fisher effect " (2004). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1207. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1207 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Threshold cointegration test of the Fisher effect by Biyong Xu A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Economics Program of Study Committee: Barry Falk, Major Professor Helle Bunzel Wayne Fuller Peter Orazem John Schroeter Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2004 Copyright © Biyong Xu, 2004. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3158382 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

The Early History of the Real/Nominal Interest Rate Relationship

THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE REAL/NOMINAL INTEREST RATE RELATIONSHIP Thomas M. Humphrey The proposition that the real rate of interest equals century classical and neoclassical monetary theorists, the nominal rate minus the expected rate of inflation (3) that it was presented in its modern form by the (or alternatively, the nominal rate equals the real end of the century, and therefore (4) that the notion rate plus expected inflation) has a long history ex- that it is a 20th century invention is totally erroneous. tending back more than 240 years. William Douglass In documenting these points, the article traces the articulated the idea as early as the 1740s to explain pre-20th century evolution of the real/nominal rate how the overissue of colonial currency and the re- analysis from its earliest origins to its culmination in sulting depreciation of paper money relative to coin Fisher’s Appreciation and Interest. As a preliminary raised the yield on loans denominated in paper com- step, however, it is necessary to sketch the basic pared to the yield on loans denominated in silver coin. outlines of this traditional analysis in order to demon- In 1811 Henry Thornton used the same notion to ex- strate how earlier writers contributed to it. plain how an inflation premium was incorporated into and generated a rise in British interest rates during Key Propositions the Napoleonic wars. Jacob de Haas, writing in 1889, employed the real/nominal rate idea to account for the As usually presented; the real/nominal interest “third (inflationary) element” in interest rates, the rate relationship expresses the nominal rate as the other two being a reward for capital and a payment sum of the real rate and a premium for expected for risk. -

'Ecozone': Implications for Monetary Models of Exchange Rate Determinati

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Validity Assessments of International Parity in the ‘Ecozone’: Implications for Monetary Models of Exchange Rate Determination Mogaji, Peter Kehinde University of Sunderland in London 10 June 2019 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/98945/ MPRA Paper No. 98945, posted 11 Mar 2020 13:06 UTC Validity Assessments of International Parity in the ‘Ecozone’: Implications for Monetary Models of Exchange Rate Determination by Peter Kehinde Mogaji University of Sunderland in London Abstract In proposing monetary integration, the fifteen-member Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) resolved to evolve and adopt a single currency, ‘eco’ across the African sub-continent by January 2020.This proposed monetary region is consequently styled by this author as ‘proposed Ecozone’. This paper appraised the international parity conditions in the proposed monetary union with specific focus on purchasing power parity (PPP), international Fisher Effect (IFE) and uncovered interest parity (UIP). The examination of simultaneous validity of these postulations and theories in the cases of the 15-countries were performed through the investigation of directions of bilateral relationship of the countries of the Ecozone. Monthly, quarterly and annual data spanning averagely over a period of 28 years between 1990 and 2017 were employed in this study. Residual-based cointegration test methods of Engle-Granger, Philip-Ouliaris and Park’s Added Variable and the Johansen cointegration tests were applied in evaluating these parity conditions. Results generated by various empirical estimations generally revealed that the international parity theoretical propositions of absolute PPP, relative PPP, international Fisher Effects and the uncovered interest parity are hugely not valid across the proposed ‘Ecozone’. -

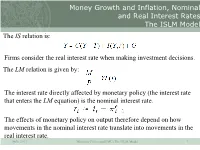

Money Growth and Inflation, Nominal and Real Interest Rates the ISLM Model the IS Relation Is

Money Growth and Inflation, Nominal and Real Interest Rates The ISLM Model The IS relation is: Firms consider the real interest rate when making investment decisions. The LM relation is given by: The interest rate directly affected by monetary policy (the interest rate that enters the LM equation) is the nominal interest rate. The effects of monetary policy on output therefore depend on how movements in the nominal interest rate translate into movements in the real interest rate. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: The ISLM Model 1 Figure: Nominal and Real One-Year T-Bill Rates in the United States since 1978 SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: The ISLM Model 2 Figure: Expected and actual inflation rates for Germany, 1972 -2005 SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: The ISLM Model 3 Money Growth and Inflation, Nominal and Real Interest Rates The ISLM Model • Higher money growth leads to lower nominal interest rates in the short run but to higher nominal interest rates in the medium run. • Higher money growth leads to lower real interest rates in the short run but has no effect on real interest rates in the medium run. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: The ISLM Model 4 Figure: Equilibrium Output and Interest Rates The ISLM Model The equilibrium level of output and the equilibrium nominal interest rate are given by the intersection of the IS curve and the LM curve. The real interest rate equals the nominal interest rate minus expected inflation. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: The ISLM Model 5 Figure: The Short-Run Effects of an Increase in Money Growth The ISLM Model An increase in money growth increases the real money stock (M/P) in the short run. -

MONEY and BANKING

MONEY and BANKING: ECON 3115 Revised, Fall 2011 Professor Benjamin Russo Chapter 4: Understanding Interest Rates To simplify discussion these notes ignore important economic differences between financial intermediaries and financial markets. Instead, the notes treat the financial system as one big happy family. Outline I) What is the „Present Value‟ of an Asset? How is Present Value Calculated? II) Interest Rates and Yield to Maturity III) Interest Rates versus Rates of Return IV) Interest Rate Risk V) “The” Interest Rate and Economic Efficiency VI) The Real Interest Rate versus the Nominal Interest Rate I) What is the „Present Value‟ of an Asset? How is Present Value Calculated? 1) Present Value (PV) is a fundamental concept in financial economics. For this reason, you need to understand the concept and how to calculate it. Start with the concept. Generally speaking, the PV of an asset is the current value of future income the asset is expected to produce, after the future income is discounted by the "opportunity cost of owning the asset." The opportunity cost of owning an asset is the future income that could have been earned if the owner had bought the next best alternative asset. E.G., suppose Ms. Penny-pincher ranks four different assets with the colorful names Red, Blue, Green, and Fuchsia. Ms. P. ranks Blue highest, and buys only Blue. She ranks Green second highest, but does not buy Green. Thus, Ms. P. foregoes the opportunity to earn income from Green. The foregone Green income is the opportunity cost of owning Blue. 2) The opportunity cost of owning an asset often is called the "time value of money" because it is the value one could have achieved, over time, had "money" been invested differently.