“The Evolution of Educational Reform in Thailand”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

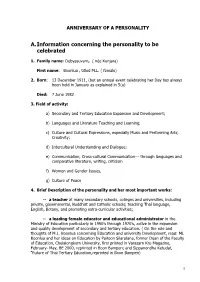

A. Information Concerning the Personality to Be Celebrated

ANNIVERSARY OF A PERSONALITY A. Information concerning the personality to be celebrated 1. Family name: Debyasuvarn, ( née Kunjara) First name: Boonlua , titled M.L. ( female) 2. Born: 13 December 1911, (but an annual event celebrating her Day has always been held in January as explained in 5(a) Died: 7 June 1982 3. Field of activity: a) Secondary and Tertiary Education Expansion and Development; b) Languages and Literature Teaching and Learning; c) Culture and Cultural Expressions, especially Music and Performing Arts; Creativity; d) Intercultural Understanding and Dialogue; e) Communication, Cross-cultural Communication--- through languages and comparative literature, writing, criticism f) Women and Gender Issues, g) Culture of Peace 4. Brief Description of the personality and her most important works: -- a teacher at many secondary schools, colleges and universities, including private, governmental, Buddhist and Catholic schools; teaching Thai language, English, Botany, and promoting extra-curricular activities; -- a leading female educator and educational administrator in the Ministry of Education particularly in 1950’s through 1970’s, active in the expansion and quality development of secondary and tertiary education. ( On the role and thoughts of M.L. Boonlua concerning Education and university Development, read: ML Boonlua and her ideas on Education by Paitoon Silaratana, former Dean of the Faculty of Education, Chulalongkorn University, first printed in Varasarn Kru Magazine, February- May, BE 2000, reprinted in Boon Bampen; and -

Language Policy and Bilingual Education in Thailand: Reconciling the Past, Anticipating the Future1

LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network Journal, Volume 12, Issue 1, January 2019 Language Policy and Bilingual Education in Thailand: Reconciling the Past, Anticipating the Future1 Thom Huebner San José State University, USA [email protected] Abstract Despite a century-old narrative as a monolingual country with quaint regional dialects, Thailand is in fact a country of vast linguistic diversity, where a population of approximately 60 million speak more than 70 languages representing five distinct language families (Luangthongkum, 2007; Premsrirat, 2011; Smalley, 1994), the result of a history of migration, cultural contact and annexation (Sridhar, 1996). However, more and more of the country’s linguistic resources are being recognized and employed to deal with both the centrifugal force of globalization and the centripetal force of economic and political unrest. Using Edwards’ (1992) sociopolitical typology of minority language situations and a comparative case study method, the current paper examines two minority language situations (Ferguson, 1991), one in the South and one in the Northeast, and describes how education reforms are attempting to address the economic and social challenges in each. Keywords: Language Policy, Bilingual Education, the Thai Context Background Since the early Twentieth Century, as a part of a larger effort at nation-building and creation of a sense of “Thai-ness.” (Howard, 2012; Laungaramsri, 2003; Simpson & Thammasathien, 2007), the Thai government has pursued a policy of monolingualism, establishing as the standard, official and national language a variety of Thai based on the dialect spoken in the central plains by ethnic Thais (Spolsky, 2004). In the official narrative presented to the outside world, Thais descended monoethnic and monocultural, from Southern China, bringing their language with them, which, in contact with indigenous languages, borrowed vocabulary. -

Recruitment Guide for Thailand. INSTITUTION Institute of International Education/Southeast Asia, Bangkok (Thailand).; Citibank, N.A., Bangkok (Thailand)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 421 071 HE 031 416 AUTHOR Yoshihara, Shoko, Comp. TITLE Recruitment Guide for Thailand. INSTITUTION Institute of International Education/Southeast Asia, Bangkok (Thailand).; Citibank, N.A., Bangkok (Thailand). ISBN ISBN-0-87206-245-7 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 148p. AVAILABLE FROM Institute of International Education/Southeast Asia, Citibank Tower, 9th Floor, 82 North Sathorn Road, Bangkok 10500 Thailand. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS College Admission; Cultural Influences; Foreign Countries; *Foreign Students; Higher Education; Student Characteristics; *Student Recruitment IDENTIFIERS *Thailand ABSTRACT This book is intended to provide U.S. university recruiters with information on higher education and student recruitment opportunities in Thailand. Section A describes recruitment strategies that are professionally and culturally appropriate to Thailand; contact information concerning related institutions is also included. A subsection called "What Thai Students Are Like" identifies the basic characteristics of Thai students. Section B offers detailed information on the development and present situation of higher education in Thailand. Directories of public/private universities and the addresses of related government ministries are included. Finally, in Section C, a basic country profile of Thailand covers such aspects as history, religion, and the language. Attachments to each section provide relevant addresses. Tables provide information on the academic calendar, -

Children's Education by Folklore in Thailand Historical Background of Education in Thailand

feature Children's Education by folklore in Thailand Historical background of Education in Thailand by Khunying Maenmas Chavalit ducation of children in Thailand, before the were oral explanation, demonstration and supervi- reformation of its educational system, was sion on the child who was taught to listen, E under the responsibilities of three institu- memorise and practice. The child was also ex- tions; namely the family, the temple, and the King. pected to ask questions, although this activity was The education system was reformed in Buddhist not much encouraged. Era (B.E.) 2411-2453 (A.D. 1868-1910) during the Four activities were required for learning: reign of King Chulalongkorn, who initiated the Suttee (listening);Jitta (thinking); Pucha (inquir- modernization programme of the country's socio- ing), and Likhit (writing). economy and political infrastructure. Before then, The subjects taught were mainly spiritual, there had been no schools in the modern sense; vocational and literary. Girls were given instruc- neither were there a systematically prescribed tions at home, by the mother, the grandmother curriculum and teachers trained in teaching meth- or female adult relatives. They learned etiquette, ods. Knowledgeable persons who were willing to cooking, household management, grass or cane teach, would apply and transfer their knowledge weaving, and most important of all, textile weav- which they had acquired through years of prac- ing. Textile weaving was not only to provide gar- tice, observations, analysis or which they had in- ments for the family, but was also regarded as a herited from their parents. The methods used prestige, and a requirement for respectable women. -

Children and Youth in Thailand

1 Children and Youth in Thailand Wirot Sanrattana Merrill M. Oaks Being published 2 National Profile Thailand is a rich tapestry of traditional and modern culture. Located in Southeastern Asia, bordering the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand, southeast of Myanmar (Burma) – see map. “Siam” is the name by which the country was known to the world until 1949. On May 11, 1949 an official proclamation changed the name to “Prathet Thai” or “Thailand”. The word “Thai” means “free”, and therefore “Thailand” means “Land of the Free”. Thailand’s known as the “Land of Smiles” for the friendliness of its people. A unified Thai kingdom was established in the mid-14th century. Thailand is the only Southeast Asian country never to have been taken over by a European or other world power. A bloodless revolution in 1932 led to a constitutional monarchy. The provisions relating in the constitutional government and monarchy laid down in the 1932 Constitution specified three basic concepts regarding the governmental structure. First, the Monarch is regarded as Head of State, Head of the Armed Forces and Upholder of the Buddhist Religion and all other religions. Second, a bicameral National Assembly, which is comprised of members of Parliament and members of Senate, administers the legislative branch. Third, the Prime Minister as head of the government and chief executive oversees the executive branch covering the Council of Ministers which is responsible for the administration of 19 ministries and the Office of the Prime Minister. Buddhism is the pre-dominate religion with a minority of other world religions represented throughout the nation. -

Thailand Case Study: School Vaccination Checks

Case Study: Checking vaccination status at entry to, or during, school THAILAND Law or policy What is the law or Vaccination history check at school entry is a “recommended” policy, i.e. policy? it is not a mandatory policy. Year first established? 2013 Who issued the law or The policy was supported by the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) and the policy? Ministry of Education (MoE) as part of Component 5 of the Health Promoting Schools Initiative (HPS). Scope? All schools under the MoE, Office of Basic Education Commission. Implementation Funding Although all hospitals and health centres provide immunization services free of charge, no additional funding is provided to schools to support school-based immunization activities nor for the checking of vaccination status. Resources are generated by a network of leaders, parents and students when needed. Who checks? The teachers of the children entering Grade 1 and Grade 7 collect the immunization history record from parents, and make a photocopy. The responsible health officer then checks the immunization histories for completeness. Information used to The immunization history of the child is contained in the Mother and Child check vaccination status Health Handbook or other vaccination card. What is done if children If a child is identified as un- or incompletely vaccinated, they are either are missing doses? referred to the local hospital or health centre to receive catch-up vaccines, or in some schools, health care staff may come to the school to deliver catch-up vaccines. An accelerated vaccination schedule is included in the national immunization programme schedule to provide guidance on how to vaccinate older children up to 7 years of age who have missed vaccines. -

Thailand Food Security and Nutrition Case Study Successes and Next Steps

Thailand food security and nutrition case study Successes and next steps Draft report for South-South Learning Workshop to Accelerate Progress to End Hunger and Undernutrition 20 June, 2017, Bangkok, Thailand Prepared by the Compact2025 team Thailand is a middle-income country that rapidly reduced hunger and undernutrition. Its immense achievement is widely regarded as one of the best examples of a successful nutrition program, and its experiences could provide important lessons for other countries facing hunger and malnutrition (Gillespie, Tontisirin, and Zseleczky 2016). This report describes Thailand’s progress, how it achieved success, remaining gaps and challenges, and the lessons learned from its experience. Along with the strategies, policies, and investments that set the stage for Thailand’s success, the report focuses on its community-based approach for designing, implementing, and evaluating its integrated nutrition programs. Finally, key action and research gaps are discussed, as Thailand aims to go the last mile in eliminating persistent undernutrition while contending with emerging trends of overweight and obesity. The report serves as an input for discussion at the “South-South Learning to Accelerate Progress to End Hunger and Undernutrition” meeting, taking place in Bangkok, Thailand on June 20. Both the European Commission funded project, the Food Security Portal (www.foodsecuritypotal.org) and IFPRI’s global initiative Compact2025 (www.compact2025.org) in partnership with others are hosting the meeting, which aims to promote knowledge exchange on how to accelerate progress to end hunger and undernutrition through better food and nutrition security information. The case of Thailand can provide insight for other countries facing similar hunger and malnutrition problems as those Thailand faced 30 years ago. -

Shadow Education in Thailand: a Case Study of Thai English Tutors

LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network Journal, Volume 12, Issue 1, January 2019 Shadow Education in Thailand: A Case Study of Thai English Tutors’ Perspectives towards the Roles of Private Supplementary Tutoring in Improving English Language Skills Saksit Saengboon School of Language and Communication, National Institute of Development Administration, Thailand [email protected] Abstract Shadow education, particularly tutorial schools, is a familiar yet under-studied educational phenomenon in Thai society. This exploratory qualitative case study aimed at gaining a better understanding of English tutorial schools through the lens of tutors. Specifically, two tutors in Bangkok, Thailand were selected via purposive sampling. Two rounds of interviews were conducted: 1) focus group and 2) individual. Key themes emerged from the two rounds of interviews, namely challenges in providing tutorial courses, tutorial schools and Thai society, the importance of motivation, tutorials and English teaching, success and failure in tutoring and English language teaching policy. Concluding remarks suggested that shadow education, in this case private supplementary tutoring, has a potential to improve English language skills of Thais through its motivating force and that dichotomous thinking about key components of English language teaching e.g., to teach or not to teach grammar; English native speaking vs. non-native speaking teachers should be avoided. Keywords: shadow education, tutorial schools, motivation, success and failure in English tutoring Introduction The English language left the Thai royal court in 1921 (Baker, 2008) to be enjoyed by commoners and has since been studied widely in the Kingdom of Thailand. According to Trakulkasemsuk (2018), English made inroads into the Thai territory at least two hundred years ago. -

Higher Education in Thailand

14 INTERNATIONAL HIGHER EDUCATION tions receiving more incentives than do ordinary profes- sors. Higher Education in Thailand: Having described a generalized image of Scandinavian Traditions and Bureaucracy higher education, it is, however, fair to end these reflec- tions by pointing to some differences within the region. Sakda Prangpatanpon Even though the trends of the 1990s are common for all Sakda Prangpatanpon is associate professor and chair, Department of the countries, there are differences in pace and level of de- Foundations of Education, Burapha University, Bangsaen, Chonburi velopment. 20131, Thailand. He holds a Ph.D. degree from Boston College. Fax: 38-391-043. igher education as a government function is rela- Faculty are frustrated over the seem- Htively new in Thailand. The first university, ingly changed role of the university in Chulalongkorn University, was founded in 1917; a second the division of labor in society. They fear university was established in 1933; and three more were that the university is moving away from founded in 1943. These five universities, all located in its traditional role as the independent, Bangkok, were established primarily to train personnel for critical segment in society. government service. In the 1960s, three public universities were established outside the capital, one each for the north, the northeast, and the south. Private colleges also appeared What is often termed the “international” or “Ameri- around this time, and in 1969 a bill was enacted to govern can” development of higher education started first in Swe- the establishment and operation of private institutions of den, followed by Finland. These two countries have higher learning. -

ECFG-Thailand-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. The guide consists of 2 parts: Thailand Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment – Southeast Asia in particular (Photo: AF Chief shows family photos to Thai youth). Culture Guide Culture Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” information on Thailand, focusing on unique cultural features of Thai society. This section is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo: Exercise Cope Tiger Commander dines with children in Udon Thani, Thailand). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

The Burgeoning of Education in Thailand Sandrine Michel

The Burgeoning of Education in Thailand Sandrine Michel To cite this version: Sandrine Michel. The Burgeoning of Education in Thailand: a Quantitative Success. Mounier; Alain; Tangchuang; Phasina. Education and knowledge in Thailand: the quality controversy, Silkworm Books, pp.11-37, 2010. hal-02911422 HAL Id: hal-02911422 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02911422 Submitted on 23 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License 1 Postprint of Michel Sandrine (2010) The burgeoning of education in Thailand: a quantitative success, In : Mounier A & Tangchuang P, Education and Knowledge in Thailand – The Quality Controversy, Bangkok: Silkworm Books, pp. 11-37. Chapter 1 The burgeoning of education in Thailand: a quantitative success Sandrine Michel1 LASER EA, University of Montpellier The first studies on the contribution of education to the process of Asian growth stressed the extremely fast rates of development of national educational systems as well as of public expenditure (Tan and Mingat 1989; Psacharopoulos 1991;Warr 1993). The notion that Asian educational systems have performed well was gradually disseminated and gained favour (World Bank 1993; UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2004). -

ARTS EDUCATION in THAILAND: WHY IT MATTERS Cristina Penn Schoonmaker F ก ก F F F F F F ก F F F ก ก ก ก F F

ARTS EDUCATION IN and talk about a painting not only require THAILAND: WHY IT high level cognitive, visual, and language 1 skills, but also extensive contextual MATTERS knowledge, which only a background in the humanities can offer. The author 2 Cristina Penn Schoonmaker analyzes several works of art as well as discusses modern aesthetics to argue that the arts are an integral part of the human experience, and therefore, should be included in general education courses at กก the tertiary level. The soul never thinks without an image ก - Aristotle - กก More and more reputable state and private กกกก universities in Thailand have attempted to adopt an American model of a liberal arts ก ก education, and yet many of the very กก objectives of this classical curriculum— namely to create a well-rounded, ก ก enlightened, and cultured citizenry, have been lost in translation. ก In recent years, Thai policy-makers and ก parents have lost sight of the original American model by becoming product ก driven consumers who view education as a กก brand name commodity and seek to hasten their children’s education in order to have their offspring join the workforce or the family business—thereby becoming “productive” members of society. This Abstract mindset was brought home in 1999 by Prachuab Chaiyasarn, the Minister of The humanities, especially the visual arts, University Affairs at that time, when he are often neglected at Thai universities announced that universities should focus because they are perceived as rarely on becoming a “university for industry” or yielding tangible results. This paper aims a “university with industry” (as cited in to demonstrate that learning to decode Mounier and Tangchuang 2010:104).