The Ghent Altarpiece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rijksmuseum Bulletin

the rijksmuseum bulletin 114 the rijks the amsterdam paradise of herri metmuseum de bles and the fountain of life bulletin The Amsterdam Paradise by Herri * met de Bles and the Fountain of Life • boudewijn bakker • ne of the most intriguing early Fig. 1 the birds, the creatures of the land and O landscape paintings in the herri met de bles, human beings.2 The Creator made man Rijksmuseum is Paradise by Herri met Paradise, c. 1541-50. a place to dwell, ‘a garden eastward in de Bles (fig. 1). The more closely the Oil on panel, Eden’, with the tree of life and the tree 46.6 x 45.5 cm. modern-day viewer examines this of the knowledge of good and evil, and Amsterdam, small panel with its extremely detailed Rijksmuseum, a river that watered the garden, then scene, the more questions it raises. inv. no. sk-a-780. parted to become four branches. The Several authors have consequently artist shows us the two primal trees in endeavoured to coax the work into paradise, and the source of the primal giving up its secrets. river in the form of an elegant fountain The panel is round and has a sawn with four spouts.3 bevelled edge. It was almost certainly In this idyllic setting, which occupies originally contained in a carved round roughly the lower half of the landscape, wooden frame that was later removed.1 Bles pictures the tragic story of the Fall The composition is divided into con- in four scenes, following the sequence centric bands around a circular central of the days of the Creation: the creation section in which we see paradise; beside of Eve from Adam’s rib, God forbidding and behind it is a panoramic ‘world them to eat fruit from the tree of the landscape’. -

Reciprocal Desire in the Seventeenth Century

CHAPTER 8 The Painting Looks Back: Reciprocal Desire in the Seventeenth Century Thijs Weststeijn The ancients attributed the invention of painting to an act of love: Butades’s daughter tracing her lover’s shadow on a wall, according to Pliny.1 Likewise, the greatest works were deemed to spring from the artist’s infatuation with his model, from Apelles and Campaspe to Raphael and his Fornarina.2 Ever since Ovid’s Ars amatoria, the art of love had been seen as a discipline more refined than the art of painting, which the Romans did not discuss with similar sophistication. By the late sixteenth century, however, courtiers’ literature had become a conduit between poetic and artistic endeavours, ensuring that the nuanced vocabulary of amorous talk affected the theory of painting.3 In Italian and Dutch sources, both the making and the appreciation of art were described in terms of the lover’s interest in a woman: Dame Pictura. She was a vrijster met vele vrijers: a lady with a host of swains, in the words of the artists’ biographer Cornelis de Bie.4 True artists came to their trade by falling helplessly in love The research resulting in this article was sponsored by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research. 1 Bie Cornelis de, Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst (Antwerp, Meyssens van Monfort: 1661) 23. 2 Hoogstraten Samuel van, Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst (Rotterdam, Van Hoogstraten: 1678) 291: ‘Urbijn, toen hy verlieft was; Venus deede hem Venus op het schoonst ten toon brengen […] Het geen onmooglijk schijnt kan de liefde uitvoeren, want de geesten zijn wakkerst in verliefde zinnen’. -

HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 28, No. 1 April 2011 Jacob Cats (1741-1799), Summer Landscape, pen and brown ink and wash, 270-359 mm. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Christoph Irrgang Exhibited in “Bruegel, Rembrandt & Co. Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850”, June 17 – September 11, 2011, on the occasion of the publication of Annemarie Stefes, Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850, Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle (see under New Titles) HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Dagmar Eichberger (2008–2012) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009–2013) Matt Kavaler (2008–2012) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010–2014) Exhibitions -

Curriculum Vitae of Maryan Wynn Ainsworth

Curriculum Vitae of Maryan Wynn Ainsworth Department of European Paintings The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1000 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10028 Phone: (212) 396-5172 Fax: (212) 396-5052 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Yale University, New Haven, Conn., Department of History of Art Ph.D., May 1982 M. Phil., May 1976 Doctoral dissertation, “Bernart van Orley as a Designer of Tapestry” Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio, Department of Art History M.A., May 1973 B.A., January 1972 Master’s thesis, “The Master of St. Gudule” Independent art-history studies in Vienna (1969), Mainz (1973–74), and Brussels (1976–77) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Department of European Paintings Curator of European Paintings, 2002–present Research on Northern Renaissance paintings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, with emphasis on the integration of technical examination of paintings with art-historical information; curating exhibitions; cataloguing the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Netherlandish and German paintings in the collection; teaching courses on connoisseurship and Northern Renaissance paintings topics for Barnard College and Columbia University; directing the Slifka Fellowship program for art historians at the graduate level; departmental liaison and coordinator, European Paintings volunteers (2008–16) Paintings Conservation, Conservation Department Senior Research Fellow, 1992–2001 Research Fellow, 1987–92 Senior Research Associate, 1982–87 Research Investigator, 1981–82 Interdisciplinary research -

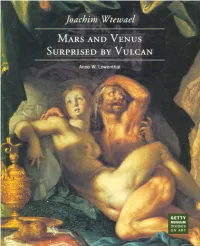

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan

Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Anne W. Lowenthal GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Malibu, California Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Joachim Wtewael (Dutch, 1566-1638). Cynthia Newman Bohn, Editor Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, Amy Armstrong, Production Coordinator circa 1606-1610 [detail]. Oil on copper, Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 20.25 x 15.5 cm (8 x 6/8 in.). Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PC.274). © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Frontispiece: Malibu, California 90265-5799 Joachim Wtewael. Self-Portrait, 1601. Oil on panel, 98 x 74 cm (38^ x 29 in.). Utrecht, Mailing address: Centraal Museum (2264). P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Library of Congress indicated. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowenthal, Anne W. Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Joachim Wtewael : Mars and Venus Austin, Texas surprised by Vulcan / Anne W. Lowenthal. Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., p. cm. Hong Kong (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89236-304-5 i. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638. Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan. 2. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638 — Criticism and inter- pretation. 3. Mars (Roman deity)—Art. 4. Venus (Roman deity)—Art. 5. Vulcan (Roman deity)—Art. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Title. III. Series. ND653. W77A72 1995 759-9492-DC20 94-17632 CIP CONTENTS Telling the Tale i The Historical Niche 26 Variations 47 Vicissitudes 66 Notes 74 Selected Bibliography 81 Acknowledgments 88 TELLING THE TALE The Sun's loves we will relate. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

November 2012 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 29, No. 2 November 2012 Jan and/or Hubert van Eyck, The Three Marys at the Tomb, c. 1425-1435. Oil on panel. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. In the exhibition “De weg naar Van Eyck,” Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, October 13, 2012 – February 10, 2013. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 Paul Crenshaw (2012-2016) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009-2013) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Exhibitions ............................................................................ 3 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010-2014) -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Fashionable Mourners: Bronze Statuettes from the Rijksmuseum

Fashionable Mourners: Bronze Statuettes from the Rijksmuseum by Amanda Mikolic, Curatorial Assistant Cleveland’s celebrated early fifteenth-century alabaster tomb Figure 1. Mourners mourners are part of a major exhibition at the renowned from the Tomb of Philip the Bold, Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam this fall (fig. 1). In exchange, the Duke of Burgundy (r. Cleveland Museum of Art has the rare opportunity to exhibit 1363–1404), 1404–10. Claus de Werve four bronze mourners—traveling to North America for the (Netherlandish, first time—from the tomb of Isabella of Bourbon (1436–1465) 1380–1439). Vizille ala- (fig. 2). The original carvings are attributed to Jan Borman the baster; avg. h. 41.4 cm. The Cleveland Museum Younger and the casting attributed to Renier van Thienen. of Art, Bequest of Leonard C. Hanna Jr., 1940.128, 1958.66–67. Figure 2. Mourners from the Tomb of Isabella of Bourbon, c. 1475–76. Attributed to Jan Borman the Younger (Netherlandish, active 1479–1520); casting at- tributed to Renier van Thienen (Flemish, ac- tive 1460–1541). Brass copper alloy; avg. h. 56 cm. On loan from the City of Amsterdam, BK-AM-33-B, I, D, F. 2 3 Figure 3. Portrait of for overseeing the construction of Isabella’s tomb in addition to Isabella of Bourbon, c. casting the bronze mourners from wooden models attributed 1500. After Rogier van der Weyden (Flemish, to carver Jan Borman, who often worked with Van Thienen and c. 1399–1464). Musée was known in Brussels as a master of figural sculpture. des Beaux-Arts, Dijon, France. -

Hat, Cap, Hood, Mitre

CHAPTER 1 Headgear: Hat, Cap, Hood, Mitre Introduction down over his shoulders;4 and in Troilus and Criseyde Pandarus urges his niece, a sedate young widow, to Throughout the later Middle Ages (the twelfth to early cast off her face-framing barbe, put down her book and sixteenth centuries), if we are to believe the evidence of dance.5 art, some kind of headgear was worn by both sexes in- In art of the middle medieval period (from about doors and out: at dinner, in church, even in bed. This is the eighth to the eleventh centuries), headgear is less understandable if we consider the lack of efficient heat- well attested. Men are usually depicted bareheaded. ing in medieval buildings, but headgear was much more Women’s heads and necks are wrapped in voluminous than a practical item of dress. It was an immediate mark- coverings, usually depicted as white, so possibly linen is er of role and status. In art, it is possible to distinguish being represented in most cases. There is no clue to the immediately the head of a man from that of woman, as shape of the piece of cloth that makes up this headdress, for example in a fourteenth-century glass panel with a sa- how it is fastened, or whether there is some kind of cap tirical depiction of a winged serpent which has the head beneath it to which it is secured. Occasionally a fillet is of a bishop, in a mitre, and a female head, in barbe* and worn over, and more rarely under, this veil or wimple. -

The Early Netherlandish Underdrawing Craze and the End of a Connoisseurship Era

Genius disrobed: The Early Netherlandish underdrawing craze and the end of a connoisseurship era Noa Turel In the 1970s, connoisseurship experienced a surprising revival in the study of Early Netherlandish painting. Overshadowed for decades by iconographic studies, traditional inquiries into attribution and quality received a boost from an unexpected source: the Ph.D. research of the Dutch physicist J. R. J. van Asperen de Boer.1 His contribution, summarized in the 1969 article 'Reflectography of Paintings Using an Infrared Vidicon Television System', was the development of a new method for capturing infrared images, which more effectively penetrated paint layers to expose the underdrawing.2 The system he designed, followed by a succession of improved analogue and later digital ones, led to what is nowadays almost unfettered access to the underdrawings of many paintings. Part of a constellation of established and emerging practices of the so-called 'technical investigation' of art, infrared reflectography (IRR) stood out in its rapid dissemination and impact; art historians, especially those charged with the custodianship of important collections of Early Netherlandish easel paintings, were quick to adopt it.3 The access to the underdrawings that IRR afforded was particularly welcome because it seems to somewhat offset the remarkable paucity of extant Netherlandish drawings from the first half of the fifteenth century. The IRR technique propelled rapidly and enhanced a flurry of connoisseurship-oriented scholarship on these Early Netherlandish panels, which, as the earliest extant realistic oil pictures of the Renaissance, are at the basis of Western canon of modern painting. This resulted in an impressive body of new literature in which the evidence of IRR played a significant role.4 In this article I explore the surprising 1 Johan R. -

A Latter-Day Saint Exegesis of the Blood and Water Imagery in the Gospel of John

Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Volume 1 Article 4 2009 “And the Word Was Made Flesh”: A Latter-day Saint Exegesis of the Blood and Water Imagery in the Gospel of John Eric D. Huntsman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Huntsman, Eric D. (2009) "“And the Word Was Made Flesh”: A Latter-day Saint Exegesis of the Blood and Water Imagery in the Gospel of John," Studies in the Bible and Antiquity: Vol. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba/vol1/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in the Bible and Antiquity by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title “And the Word Was Made Flesh”: A Latter-day Saint Exegesis of the Blood and Water Imagery in the Gospel of John Author(s) Eric D. Huntsman Reference Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 1 (2009): 51–65. ISSN 2151-7800 (print), 2168-3166 (online) Abstract Critical to understanding the widespread symbol- ism and imagery pointing to Jesus Christ in the New Testament is an exegetical grasp of the content— that is, an understanding of the historical, literary, and theological context of the language. The image of water recurs frequently throughout the New Testament Gospels as a symbol of the Savior’s purity, cleansing power, true doctrine, and so forth. Similarly, blood is used often to reflect the sacred mission of Christ and the price of our salvation.