Accelerated Internationalization by Emerging Multinationals: Emerging Multinationals: the Case of White Goods the Case of White Goods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haier Group Corporation Is a Chinese Multinational Home Appliances and Consumer Electronics Company Headquartered in Qingdao, China

Haier Group Corporation is a Chinese multinational home appliances and consumer electronics company headquartered in Qingdao, China. It designs, develops, manufactures and sells products including refrigerators, air conditioners, washing machines, microwave ovens, mobile phones, computers, and televisions. The home appliances business, namely Haier Smart Home, has seven global brands – Haier, Casarte, Leader, GE Appliances, Fisher & Paykel, Aqua and Candy. According to data released by Euromonitor,[1] Haier is the number one brand globally in major appliances for 10 consecutive years from 2009 In June 2015 Haier Group acquired General Electric's appliance division for $5.4 billion. GE Appliances is headquartered in Louisville, KY. GE Appliances is a formally American appliance manufacturer based in Louisville, Kentucky, USA. It is majority owned by Haier. It is one of the largest appliance brands in the United States and manufactures appliances under a house of brands[4] which include: GE, GE Profile, Café, Monogram, Haier and Hotpoint. Haier also owns FirstBuild, a global co-creation community and state-of-the-art micro-factory[5] on the University of Louisville's campus in Louisville, Kentucky. A second FirstBuild location is in Korea and the latest FirstBuild location is in India. The company was owned by General Electric until 2015, and was previously known as GE Appliances & Lighting and GE Consumer & Industrial. 1 • BRAINSTORMING PROTOTYPING FABRICATION ASSEMBLY • For a complete list of machines and specifications, visit the FirstBuild Microfactory Wiki. 2 3 GENERAL MOTORS – SAIC, CHINESE AUTO MAKER SAIC General Motors Corporation Limited (More commonly known as SAIC--GM; Chinese: 上汽通用汽车; formerly known as Shanghai General Motors Company Ltd, Shanghai GM; Chinese: 上海通用汽车) is a joint venture between General Motors Company and the Chinese SAIC Motor that manufactures and sells Chevrolet, Buick, and Cadillac brand automobiles in Mainland China. -

I, No:40 Sayılı Tebliği'nin 8'Nci Maddesi Gereğince, Hisse Senetleri

Sermaye Piyasas Kurulu’nun Seri :I, No:40 say l Teblii’nin 8’nci maddesi gereince, hisse senetleri Borsada i"lem gören ortakl klar n Kurul kayd nda olan ancak Borsada i"lem görmeyen statüde hisse senetlerinin Borsada sat "a konu edilebilmesi amac yla Merkezi Kay t Kurulu"u’na yap lan ba"vurulara ait bilgiler a"a da yer almaktad r. Hisse Kodu S ra Sat "a Konu Hisse Ünvan Grubu Yat r mc n n Ad -Soyad Nominal Tutar Tsp Sat " No Ünvan (TL)* 5"lemi K s t ** ** ADANA 1 ADANA Ç5MENTO E TANER BUGAY SANAY55 A.;. A GRUBU 2.235,720 ALTIN 2 ALTINYILDIZ MENSUCAT E 5SMA5L AYÇ5N VE KONFEKS5YON 0,066 FABR5KALARI A.;. ARCLK 3 ARÇEL5K A.;. E C5HAT YÜKSEKEL 31,344 ARCLK 4 ARÇEL5K A.;. E ERSAN OYMAN 19,736 ARCLK 5 ARÇEL5K A.;. E FER5DE SEZ5K 0,214 ARCLK 6 ARÇEL5K A.;. E F5L5Z EYÜPOHLU 209,141 ARCLK 7 ARÇEL5K A.;. E HANDE YED5DAL 28,180 ARCLK 8 ARÇEL5K A.;. E HAYRETT5N YAVUZ 0,206 ARCLK 9 ARÇEL5K A.;. E 5HSAN ERSEN 1.259,571 ARCLK 10 ARÇEL5K A.;. E 5RFAN ATALAY 195,262 ARCLK 11 ARÇEL5K A.;. E KEZ5BAN ONBE; 984,120 ARCLK 12 ARÇEL5K A.;. E RAFET SALTIK 23,514 ARCLK 13 ARÇEL5K A.;. E SELEN TUNÇKAYA 29,110 ARCLK 14 ARÇEL5K A.;. E YA;AR EMEK 1,142 ARCLK 15 ARÇEL5K A.;. E ZEYNEP ÖZDE GÖRKEY 2,351 ARCLK 16 ARÇEL5K A.;. E ZEYNEP SEDEF ELDEM 2.090,880 ASELS 17 ASELSAN ELEKTRON5K E ALAETT5N ÖZKÜLAHLI SANAY5 VE T5CARET A.;. -

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC REIT 0.0137% 0.0137% AEON REIT INVESTMENT CORP REIT 0.0195% 0.0195% ALEXANDER + BALDWIN INC REIT 0.0118% 0.0118% ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE EQUIT REIT USD.01 0.0585% 0.0585% ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN GOVT STIF SSC FUND 64BA AGIS 587 0.0329% 0.0329% ALLIED PROPERTIES REAL ESTAT REIT 0.0219% 0.0219% AMERICAN CAMPUS COMMUNITIES REIT USD.01 0.0277% 0.0277% AMERICAN HOMES 4 RENT A REIT USD.01 0.0396% 0.0396% AMERICOLD REALTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0427% 0.0427% ARMADA HOFFLER PROPERTIES IN REIT USD.01 0.0124% 0.0124% AROUNDTOWN SA COMMON STOCK EUR.01 0.0248% 0.0248% ASSURA PLC REIT GBP.1 0.0319% 0.0319% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.0061% 0.0061% AZRIELI GROUP LTD COMMON STOCK ILS.1 0.0101% 0.0101% BLUEROCK RESIDENTIAL GROWTH REIT USD.01 0.0102% 0.0102% BOSTON PROPERTIES INC REIT USD.01 0.0580% 0.0580% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.0000% 0.0000% BRIXMOR PROPERTY GROUP INC REIT USD.01 0.0418% 0.0418% CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG COMMON STOCK 0.0191% 0.0191% CAMDEN PROPERTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0394% 0.0394% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.0005% 0.0005% CAPITALAND COMMERCIAL TRUST REIT 0.0228% 0.0228% CIFI HOLDINGS GROUP CO LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.1 0.0105% 0.0105% CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD COMMON STOCK 0.0129% 0.0129% CK ASSET HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD1.0 0.0378% 0.0378% COMFORIA RESIDENTIAL REIT IN REIT 0.0328% 0.0328% COUSINS PROPERTIES INC REIT USD1.0 0.0403% 0.0403% CUBESMART REIT USD.01 0.0359% 0.0359% DAIWA OFFICE INVESTMENT -

Full Partner List

Full Partner List Partnerships: Spyder Digital SIIG Franklin Electronic Solidtek SIIG BenQ America HIVI Acoustics PC Treasures Electronics) Bags & Carry Cases Research Inc. StarTech.com Gear Head Standzout StarTech.com Blue Microphones HMDX Peerless Withings Inc 3Dconnexion STM Bags Symtek Gefen StarTech.com Thermaltake BodyGuardz Honeywell Home Pentax Imaging Xavier Professional Cable Acer Symtek Targus Genius USA Targus TRENDnet Boom HP Inc. Phiaton Corp. Yamaha Adesso Inc. Targus Thermaltake Gigabyte Technology Thermaltake Turtle Beach Braven IAV Lightspeaker Philips Zagg-iFrogz AIRBAC The Joy Factory TRENDnet Griffin Technology TRENDnet U.S. Robotics BTI-Battery Tech. iHome Philips Electronics Zalman USA Aluratek Thermaltake Tripp Lite Gripcase Tripp Lite Visiontek BUQU Incipio Technologies Planar Systems zBoost American Weigh Scales Twelve South Visiontek Gyration Twelve South XFX C2G InFocus Plantronics Zmodo Technology Corp ASUS Urban Armor Gear VOXX Electronics Hawking Technologies TX Systems Zalman USA CAD Audio Innovative Office Products PNY Technologies Belkin Verbatim weBoost (Wilson HP Inc. U.S. Robotics Zotac Canon Interworks Polk Audio Data Storage Products Victorinox (Wenger) Electronics) HYPER by Sanho Verbatim Case-Mate Inwin Development Q-See BodyGuardz Aleratec Inc Zagg-iFrogz Xavier Professional Cable Corporation Viewsonic Casio IOGear QFX Canon Computers & Tablets Aluratek Incipio Technologies Visiontek Centon iON Camera Reticare inc CaseLogic Acer ASUS Computer & AV Cables Computer Accessories InFocus VisTablet -

Repertorium 2018

Repertorium 2018 Technische voorschriften binneninstallaties Conform beveiligde toestellen Goedgekeurde beveiligingen Geattesteerde fluïda BELGISCHE FEDERATIE VOOR DE WATERSECTOR VZW BELGISCHE FEDERATIE VOOR DE WATERSECTOR VZW VOORWOORD 2018 : Conforme installaties : een noodzaak en een verplichting Belgaqua, de Belgische Federatie voor de Watersector is !er u de editie 2018 van het Repertorium met de Technische voorschriften binneninstallaties, de conform beveiligde en watertechnisch veilige toestellen, de goedgekeurde beveiligingen en gecerti!eerde "uïda van categorie 3 te presenteren. Het eerste gedeelte van deze brochure bevat de Technische Voorschriften inzake Binneninstallaties (ook private installaties genoemd), die op het openbaar waterleidingnet aangesloten zijn. Ze volgen de principes van de norm NBN EN 1717 “Bescherming tegen verontreiniging van drinkwater in waterinstallaties en algemene eisen voor inrichtingen ter voorkoming van verontreiniging door terugstroming” en van de daarin opgesomde productnormen (1). Vanaf begin 2004 werden deze Technische Voorschriften volledig opgenomen in het reglementair kader van toepassing in het Vlaamse Gewest (www.aqua"anders.be). Systematische controles van de nieuwe installaties werden ingevoerd zodat enkel de goedgekeurde installaties aan het net gekoppeld mogen worden. Gelijkaardige maatregelen zijn ook, volgens speci!eke modaliteiten, van toepassing in de andere Gewesten. Het Reglement (blz. 18) als dusdanig wordt voorafgegaan door een rijkelijk geïllustreerde educatieve voordracht over de Technische Voorschriften. Deze vervangt geenzins het reglementaire gedeelte. De afgevaardigden van de waterleidingbedrijven en de experten van Belgaqua zijn steeds beschikbaar om de essentiële regels toe te lichten. De werkbladen voor installaties en toestellen voor niet-huishoudelijk gebruik (Deel III) zijn reeds voor een groot deel herwerkt volgens de principes van de NBN EN 1717. Het secretariaat en onze experten zullen u graag adviseren. -

Study on the Competitiveness of the EU Gas Appliances Sector

Ref. Ares(2015)2495017 - 15/06/2015 Study on the Competitiveness of the EU Gas Appliances Sector Within the Framework Contract of Sectoral Competitiveness Studies – ENTR/06/054 Final Report Client: Directorate-General Enterprise & Industry Rotterdam, 11 August 2009 Disclaimer: The views and propositions expressed herein are those of the experts and do not necessarily represent any official view of the European Commission or any other organisations mentioned in the Report ECORYS SCS Group P.O. Box 4175 3006 AD Rotterdam Watermanweg 44 3067 GG Rotterdam The Netherlands T +31 (0)10 453 88 16 F +31 (0)10 453 07 68 E [email protected] W www.ecorys.com Registration no. 24316726 ECORYS Macro & Sector Policies T +31 (0)31 (0)10 453 87 53 F +31 (0)10 452 36 60 Table of contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Objectives and policy rationale 5 3 Main findings and conclusions 7 4 The gas appliances sector 11 4.1 Introduction 11 4.2 Definition 11 4.3 Overview of sub-sectors 16 4.3.1 Heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) 16 4.3.2 Domestic appliances 18 4.3.3 Fittings 20 4.4 The application of statistics 22 4.5 Statistical approach to sector and subsectors 23 5 Key characteristics of the European gas appliances sector 29 5.1 Introduction 29 5.2 Importance of the sector 30 5.2.1 Output 30 5.2.2 Employment 31 5.2.3 Demand 32 5.3 Production, employment, demand and trade within EU 33 5.3.1 Production share EU-27 output per country 33 5.3.2 Employment 39 5.3.3 Demand by Member State 41 5.3.4 Intra EU trade in GA 41 5.4 Industry structure and size distribution -

Bosch/Siemens Bauknecht Electrolux/AEG Liebherr Miele Unsachgemäßes Recycling Von Kühlgeräten – So Heizen Die Kühlsc

Unsachgemäßes Recycling von Kühlgeräten – so heizen die Kühlschrankhersteller den Klimawandel an! Bosch/Siemens Electrolux/AEG Miele 200.000 140.000 80.000 Tonnen CO2-Äquivalente Tonnen CO2-Äquivalente Tonnen CO2-Äquivalente Bauknecht Liebherr 150.000 100.000 Tonnen CO2-Äquivalente Tonnen CO2-Äquivalente Deutsche Umwelthilfe e.V. | Hackescher Markt 4 | 10178 Berlin | Thomas Fischer | Leiter Kreislaufwirtschaft | Tel.: 030 2400867-43 | [email protected] | www.duh.de So schaden die Geschäftsführer der fünf größten deutschen Kühlgerätehersteller dem Klima Deutschland hat ein Problem beim Recycling ausgedienter Kühlgeräte. Durch die unsachgemäße Entsorgung FCKW-haltiger Kühlschränke entweichen jährlich Treibhausgase, die die Atmosphäre so stark belasten wie eine Million Tonnen Kohlendioxid. Als Folge wird der Klima- wandel angeheizt und die Ozonschicht zerstört. Grund für das Entweichen großer Mengen FCKW aus alten Kühlgeräten sind mangelhafte Entsorgungspraktiken durch Recycler. Nach dem Stand der Technik müssten aus alten FCKW-haltigen Kühlgeräten mindestens 90 Prozent der enthaltenen Treibhausgase entnommen werden. Tatsächlich sind es in deutschen Recyclinganlagen aber nur 63 Prozent. Der Rest entweicht in die Umwelt. Hierfür tragen die Kühlgerätehersteller die Verantwortung, denn sie sind gesetzlich zur Entsorgung zurückgegebener Geräte verpflichtet. Die beauftragten Recycler arbeiten in Deutschland deshalb schlecht, weil die Hersteller das zulassen. Wie viel jeder der fünf großen Hersteller zur Klimaerwärmung beiträgt, hat die DUH anhand ihres geschätzten Marktanteils ermittelt. BSH Hausgeräte GmbH Vorsitzender der Geschäftsführung: Dr. Karsten Ottenberg Geschätzter Marktanteil Kühlgeräte: 20 Prozent Von der DUH geschätzter Anteil vermeidbarer Klimagas- 200.000 Tonnen CO -Äquivalente emissionen durch unsachgemäßes Kühlgeräterecycling: 2 Den konzernweiten CO -Fußabdruck zu reduzieren, ist für die BSH ein wichtiger Aussage aus dem Nachhaltigkeitsbericht: 2 Beitrag zu mehr Klimaschutz. -

Turkish Airlines Aviation

GENEL-PUBLIC March 8, 2018 Equity Research Turkish Airlines Aviation Company update Europeans are back Strong demand continue to support industry. Turkish Airlines recorded 15.5% YoY O&D pax growth, resulting in overall 8.4% BUY YoY international pax growth in 2017. In the same year, although foreign arrivals to Turkey recovered much by 27.8% YoY almost in Share price: TL17.37 all regions, European arrivals stayed flattish in 2017. Our conversations with Association of Turkish Travel Agencies claimed Target price: TL21.60 that summer bookings from Western Europe has jumped much by 60% YoY for 2018. Furthermore, summer bookings from domestic Expected Events tourist figures jumped to 6 million versus 5 million in previous year. We now estimate Turkish Airlines will carry 42.2 mn international March THY February-18 traffic passenger and 33.1 mn domestic passenger, overall resulting to April, 9th Market traffic results (March) 9.7% YoY passenger growth and improvement of 2.9 ppt in load factor to 82.1% in 2018E vs 79.1% in 2017. Although we revised up our revenue estimate of 2018E much by 6.7%, we cut down EBITDA margin estimate by 1ppt on the back of upward revision in our oil estimates and ex-fuel CASK by 5.9% after 4Q17 results Key Data performing worse than our estimates. Accordingly, we project THY to generate 13.2% revenue and 9.9% EBITDA CAGR over our Ticker THYAO forecast period (2017-2019E). Share price (TL) 17.37 There is still room for improvement on our assumptions. The 52W high (TL) 19.57 shares have gained 10.7% so far this year outperforming the 52W low (TL) 5.38 benchmark BIST 100 index by 9.4 percentage points. -

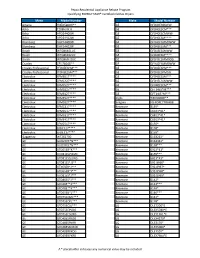

Pepco Residential Appliance Rebate Program Qualifying ENERGY STAR® Certified Clothes Dryers Make Model Number Make Model Number

Pepco Residential Appliance Rebate Program Qualifying ENERGY STAR® Certified Clothes Dryers Make Model Number Make Model Number Amana YNED5800H** GE GFD49ERSKWW Asko T208H.W.U GE GFD40ESCM*** Beko HPD24400W GE GFD40ESCMWW Beko HPD24412W GE GFD40ESM**** Blomberg DHP24400W GE GFD40ESMM0WW Blomberg DHP24412W GE GFD43ESSM*** Bosch WTG86401UC GE GFD43ESSMWW Bosch WTG86402UC GE GFD45ESM**** Bosch WTG865H2UC GE GFD45ESMM0DG Crosley CED7464G** GE GFD45ESMM0WW Crosley Professional YFD45ESPM*** GE GFD45ESPM*** Crosley Professional YFD45ESSM*** GE GFD45ESPMDG Electrolux EFME617**** GE GFD45ESSM*** Electrolux EFMC427**** GE GFD45ESSMWW Electrolux EFMC527**** GE GFV40ESCM*** Electrolux EFMC627**** GE GFT14ES*M*** Electrolux EFME427**** GE GFT14JS*M*** Electrolux EFME527**** Inglis YIED5900H** Electrolux EFME627**** Insignia NS-FDRE77WH8B Electrolux EFMC417**** Kenmore 8139* Electrolux EFMC517**** Kenmore C6163*61* Electrolux EFMC617**** Kenmore C6813*41* Electrolux EFME417**** Kenmore C6913*41* Electrolux EFME517**** Kenmore 6155* Electrolux EFDC317**** Kenmore 8158* Electrolux EFDE317**** Kenmore 8159* Gaggenau WT262700 Kenmore 6163261* GE GUD27EE*N*** Kenmore 6163361* GE GUD37EE*N*** Kenmore 8158*** GE GTD65EB*K*** Kenmore 6913*41* GE GTD81ESPJ2MC Kenmore 8159*** GE GTD81ESSJ2WS Kenmore 6813*41* GE GTD81ES*J2** Kenmore 592-8966* GE GTX65EB*J*** Kenmore 592-8967* GE GTD65EB*J*** Kenmore 592-8968* GE GTD81ES*J*** Kenmore 592-8969* GE GTD86ES*J*** Kenmore 6142* GE GFD49E**K*** Kenmore 6142*** GE GFD48E**K*** Kenmore 6146* GE GTD65EB*L*** Kenmore 6146*** -

FACTORY LINKS UN & PW Bertazzoni Bosch Broan Crosley Dacor

FACTORY LINKS UN & PW Alliance (Speed Queen commercial & new domestic) http://extranet.alliancels.net/ user name: [email protected] password: marcone When home page comes up, click on "Parts" at top of page. Put cursor on "Parts Connection", slide right and click on "Parts Connection Commercial". When “Parts Connection” opens, select desired box. AppliancePartsPros.com (excellent site to see a picture of a part) http://www.appliancepartspros.com/ No password needed Bertazzoni http://claimworks.servicepower.com Log in using the following user name and password combination and click “Submit”. user name: MAR54354 (case sensitive) password: bsihqopk (case sensitive) When the next screen comes up, click on “Literature” On next screen, Make sure “Bertazzoni” is selected. Select the “Service Manual” list from the “Literature Type” drop down box. Leave the “Model” box empty and then click the “Search” button. Find the Model number that you are looking for; they will only list the beginning of the models. Click on desired model to open breakdown. http://us.bertazzoni.com Bosch https://portal.bsh-partner.com/portal(bD1lbg==)/LoginFrame.htm?PORTAL_REGIONINDEX=20 user name: marcone-ct password: parts1 When page comes up, click on "Service" in the upper left corner, then click on "QuickFinder FullScreen". Then when the next window opens, insert your model in the box under "Product" and press "Enter". Broan http://parts.broan-nutone.com/broan/Shop No password needed Crosley The following refrigerator models were built by Mabe for Crosley Corp. We do not yet carry parts for Mabe. The customer will need to call Crosley at: 336.761.1212 for parts. -

Fisher & Paykel Appliances Holdings Limited

FISHER & PAYKEL APPLIANCES HOLDINGS LIMITED TARGET COMPANY STATEMENT — IN RELATION TO A TAKEOVER OFFER BY HAIER NEW ZEALAND INVESTMENT HOLDING COMPANY LIMITED — 4 OCTOBER 2012 For personal use only For personal use only COVER: PHASE 7 DISHDRAWER TM DISHWASHER FISHER & PAYKEL APPLIANCES HOLDINGS LIMITED TARGET COMPANY STATEMENT CHAIRMAN’S LETTER 03 TARGET COMPANY STATEMENT (TAKEOVERS CODE DISCLOSURES) 07 SCHEDULE 1 — 4 25 For personal use only APPENDIX: INDEPENDENT ADVISER’S REPORT 37 CHAIRMAN’S LETTER For personal use only CHAIRMAN’S LETTER P3 Dear Shareholder Haier New Zealand Investment Holding Company Limited (“Haier”) has offered $1.20 per share to buy your shares in Fisher & Paykel Appliances Holdings Limited (“FPA”) by means of a formal takeover offer (the Offer“ ”). •• INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS RECOMMEND DO NOT ACCEPT HAIER’S OFFER •• The independent directors of FPA (Dr Keith Turner, Mr Philip Lough, Ms Lynley Marshall and Mr Bill Roest) (the “Independent Directors”) unanimously recommend that shareholders do not accept the Offer from Haier. In making their recommendation, the Independent Directors have carefully considered a full range of expert advice available to them. Therefore you should take no action. The principal reasons for recommending that shareholders do not accept are: _ Having regard to a full range of expert advice now available to the Independent Directors (including the Independent Adviser’s valuation range of $1.28 to $1.57 per FPA Share), the Independent Directors consider that the Offer of $1.20 per FPA Share does not adequately reflect their view of the value of FPA based on their confidence in the strategic direction of the Company; and _ FPA is in a strong financial position and, as the Independent Adviser notes, FPA is at a “relatively early stage of implementation of the company’s comprehensive rebuilding strategy”. -

Haier Electronics Group Co

Asia Pacific Equity Research 01 February 2016 Overweight Haier Electronics Group Co 1169.HK, 1169 HK Further Thoughts on Qingdao Haier/GE deal, Earnings Price: HK$13.72 ▼ Price Target: HK$18.00 Revisions, FY15 Result Preview Previous: HK$20.00 Qingdao Haier announced further details of its GE Appliances China acquisition. Key takeaways: 1) in the US, GE Appliances will continue Consumer to manage/enhance its brand position; Haier could leverage its existing Shen Li, CFA AC product portfolio to add differentiated offerings to GE's US product (852) 2800 8523 lines. 2) In the Chinese market, GE can leverage the strong distribution [email protected] channel and local expertise of Qingdao Haier to launch localised Bloomberg JPMA SHLI <GO> products. 3) Qingdao Haier currently sells through the retail channel in Ebru Sener Kurumlu (852) 2800-8521 the US, while GE has established channels across both retail and [email protected] contract channels. The Haier brand can leverage GE's existing George Hsu relationships through the US retail channel. GE also has long-term (852) 2800-8559 relationships with home owners, property developers, property [email protected] management agencies and hotel operators. The Haier brand can also Dylan Chu leverage off GE's strong position in these channels. 4) For first 20 years, (852) 2800-8537 Qingdao Haier has the global right to use GE brands and pay 0% royalty [email protected] J.P. Morgan Securities (Asia Pacific) Limited fees on both exclusive (food preparation, food preservation, household cleaning, household comfort appliances) and non-exclusive products Price Performance (water purifier products).