A Study on the Perception of Continental Europe's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OSB Representative Participant List by Industry

OSB Representative Participant List by Industry Aerospace • KAWASAKI • VOLVO • CATERPILLAR • ADVANCED COATING • KEDDEG COMPANY • XI'AN AIRCRAFT INDUSTRY • CHINA FAW GROUP TECHNOLOGIES GROUP • KOREAN AIRLINES • CHINA INTERNATIONAL Agriculture • AIRBUS MARINE CONTAINERS • L3 COMMUNICATIONS • AIRCELLE • AGRICOLA FORNACE • CHRYSLER • LOCKHEED MARTIN • ALLIANT TECHSYSTEMS • CARGILL • COMMERCIAL VEHICLE • M7 AEROSPACE GROUP • AVICHINA • E. RITTER & COMPANY • • MESSIER-BUGATTI- CONTINENTAL AIRLINES • BAE SYSTEMS • EXOPLAST DOWTY • CONTINENTAL • BE AEROSPACE • MITSUBISHI HEAVY • JOHN DEERE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRIES • • BELL HELICOPTER • MAUI PINEAPPLE CONTINENTAL • NASA COMPANY AUTOMOTIVE SYSTEMS • BOMBARDIER • • NGC INTEGRATED • USDA COOPER-STANDARD • CAE SYSTEMS AUTOMOTIVE Automotive • • CORNING • CESSNA AIRCRAFT NORTHROP GRUMMAN • AGCO • COMPANY • PRECISION CASTPARTS COSMA INDUSTRIAL DO • COBHAM CORP. • ALLIED SPECIALTY BRASIL • VEHICLES • CRP INDUSTRIES • COMAC RAYTHEON • AMSTED INDUSTRIES • • CUMMINS • DANAHER RAYTHEON E-SYSTEMS • ANHUI JIANGHUAI • • DAF TRUCKS • DASSAULT AVIATION RAYTHEON MISSLE AUTOMOBILE SYSTEMS COMPANY • • ARVINMERITOR DAIHATSU MOTOR • EATON • RAYTHEON NCS • • ASHOK LEYLAND DAIMLER • EMBRAER • RAYTHEON RMS • • ATC LOGISTICS & DALPHI METAL ESPANA • EUROPEAN AERONAUTIC • ROLLS-ROYCE DEFENCE AND SPACE ELECTRONICS • DANA HOLDING COMPANY • ROTORCRAFT • AUDI CORPORATION • FINMECCANICA ENTERPRISES • • AUTOZONE DANA INDÚSTRIAS • SAAB • FLIR SYSTEMS • • BAE SYSTEMS DELPHI • SMITH'S DETECTION • FUJI • • BECK/ARNLEY DENSO CORPORATION -

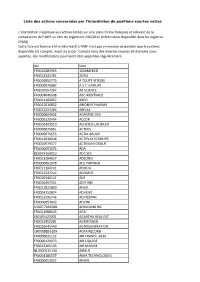

Liste Des Actions Concernées Par L'interdiction De Positions Courtes Nettes

Liste des actions concernées par l'interdiction de positions courtes nettes L’interdiction s’applique aux actions listées sur une plate-forme française et relevant de la compétence de l’AMF au titre du règlement 236/2012 (information disponible dans les registres ESMA). Cette liste est fournie à titre informatif. L'AMF n'est pas en mesure de garantir que le contenu disponible est complet, exact ou à jour. Compte tenu des diverses sources de données sous- jacentes, des modifications pourraient être apportées régulièrement. Isin Nom FR0010285965 1000MERCIS FR0013341781 2CRSI FR0010050773 A TOUTE VITESSE FR0000076887 A.S.T. GROUPE FR0010557264 AB SCIENCE FR0004040608 ABC ARBITRAGE FR0013185857 ABEO FR0012616852 ABIONYX PHARMA FR0012333284 ABIVAX FR0000064602 ACANTHE DEV. FR0000120404 ACCOR FR0010493510 ACHETER-LOUER.FR FR0000076861 ACTEOS FR0000076655 ACTIA GROUP FR0011038348 ACTIPLAY (GROUPE) FR0010979377 ACTIVIUM GROUP FR0000053076 ADA BE0974269012 ADC SIIC FR0013284627 ADEUNIS FR0000062978 ADL PARTNER FR0011184241 ADOCIA FR0013247244 ADOMOS FR0010340141 ADP FR0010457531 ADTHINK FR0012821890 ADUX FR0004152874 ADVENIS FR0013296746 ADVICENNE FR0000053043 ADVINI US00774B2088 AERKOMM INC FR0011908045 AG3I ES0105422002 AGARTHA REAL EST FR0013452281 AGRIPOWER FR0010641449 AGROGENERATION CH0008853209 AGTA RECORD FR0000031122 AIR FRANCE -KLM FR0000120073 AIR LIQUIDE FR0013285103 AIR MARINE NL0000235190 AIRBUS FR0004180537 AKKA TECHNOLOGIES FR0000053027 AKWEL FR0000060402 ALBIOMA FR0013258662 ALD FR0000054652 ALES GROUPE FR0000053324 ALPES (COMPAGNIE) -

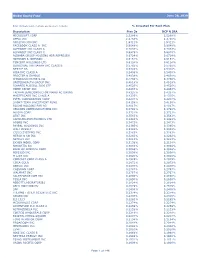

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC REIT 0.0137% 0.0137% AEON REIT INVESTMENT CORP REIT 0.0195% 0.0195% ALEXANDER + BALDWIN INC REIT 0.0118% 0.0118% ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE EQUIT REIT USD.01 0.0585% 0.0585% ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN GOVT STIF SSC FUND 64BA AGIS 587 0.0329% 0.0329% ALLIED PROPERTIES REAL ESTAT REIT 0.0219% 0.0219% AMERICAN CAMPUS COMMUNITIES REIT USD.01 0.0277% 0.0277% AMERICAN HOMES 4 RENT A REIT USD.01 0.0396% 0.0396% AMERICOLD REALTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0427% 0.0427% ARMADA HOFFLER PROPERTIES IN REIT USD.01 0.0124% 0.0124% AROUNDTOWN SA COMMON STOCK EUR.01 0.0248% 0.0248% ASSURA PLC REIT GBP.1 0.0319% 0.0319% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.0061% 0.0061% AZRIELI GROUP LTD COMMON STOCK ILS.1 0.0101% 0.0101% BLUEROCK RESIDENTIAL GROWTH REIT USD.01 0.0102% 0.0102% BOSTON PROPERTIES INC REIT USD.01 0.0580% 0.0580% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.0000% 0.0000% BRIXMOR PROPERTY GROUP INC REIT USD.01 0.0418% 0.0418% CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG COMMON STOCK 0.0191% 0.0191% CAMDEN PROPERTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0394% 0.0394% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.0005% 0.0005% CAPITALAND COMMERCIAL TRUST REIT 0.0228% 0.0228% CIFI HOLDINGS GROUP CO LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.1 0.0105% 0.0105% CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD COMMON STOCK 0.0129% 0.0129% CK ASSET HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD1.0 0.0378% 0.0378% COMFORIA RESIDENTIAL REIT IN REIT 0.0328% 0.0328% COUSINS PROPERTIES INC REIT USD1.0 0.0403% 0.0403% CUBESMART REIT USD.01 0.0359% 0.0359% DAIWA OFFICE INVESTMENT -

FCF Valuation Monitor German Small- / Midcap Companies – Q2 2020 AGENDA Executive Summary I

FCF Valuation Monitor German Small- / Midcap Companies – Q2 2020 AGENDA Executive Summary I. FCF Overview II. Market Overview III. Sector Overview IV. Sector Analysis A p p e n d i x Executive Summary The FCF Valuation FCF Valuation Monitor Recipients Monitor is a standardized report is a comprehensive valuation analysis for the German small / midcap The FCF Valuation Monitor targets the following recipients: on valuations in the market segment and is published by FCF on a quarterly basis German small / ■ Institutional investors ■ Family Offices / High Net- midcap segment and ■ Private equity investors Worth Individuals is a quick reference ■ Venture capital investors ■ Corporates Selection of Companies for investors, ■ Advisors corporates and professionals The selection of companies is primarily based on the regulated market of the Deutsche Börse: Data ■ Large cap DAX 30 companies are excluded All input data is provided by S&P Capital IQ and is not independently More advanced, verified by FCF. Ratio and multiple calculations are driven based on ■ Certain sectors which are dominated by large cap companies detailed and / or the input data available. For additional information and disclaimer, or which are of limited relevance for a small / midcap analysis please refer to the last page customized reports have been excluded (e.g. financials, utilities, automotive are available upon manufacturers and specialty sectors such as biotech and request healthcare services / hospitals) Availability ■ The allocation of companies into a specific sector -

Factset-Top Ten-0521.Xlsm

Pax International Sustainable Economy Fund USD 7/31/2021 Port. Ending Market Value Portfolio Weight ASML Holding NV 34,391,879.94 4.3 Roche Holding Ltd 28,162,840.25 3.5 Novo Nordisk A/S Class B 17,719,993.74 2.2 SAP SE 17,154,858.23 2.1 AstraZeneca PLC 15,759,939.73 2.0 Unilever PLC 13,234,315.16 1.7 Commonwealth Bank of Australia 13,046,820.57 1.6 L'Oreal SA 10,415,009.32 1.3 Schneider Electric SE 10,269,506.68 1.3 GlaxoSmithKline plc 9,942,271.59 1.2 Allianz SE 9,890,811.85 1.2 Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing Ltd. 9,477,680.83 1.2 Lonza Group AG 9,369,993.95 1.2 RELX PLC 9,269,729.12 1.2 BNP Paribas SA Class A 8,824,299.39 1.1 Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. 8,557,780.88 1.1 Air Liquide SA 8,445,618.28 1.1 KDDI Corporation 7,560,223.63 0.9 Recruit Holdings Co., Ltd. 7,424,282.72 0.9 HOYA CORPORATION 7,295,471.27 0.9 ABB Ltd. 7,293,350.84 0.9 BASF SE 7,257,816.71 0.9 Tokyo Electron Ltd. 7,049,583.59 0.9 Munich Reinsurance Company 7,019,776.96 0.9 ASSA ABLOY AB Class B 6,982,707.69 0.9 Vestas Wind Systems A/S 6,965,518.08 0.9 Merck KGaA 6,868,081.50 0.9 Iberdrola SA 6,581,084.07 0.8 Compagnie Generale des Etablissements Michelin SCA 6,555,056.14 0.8 Straumann Holding AG 6,480,282.66 0.8 Atlas Copco AB Class B 6,194,910.19 0.8 Deutsche Boerse AG 6,186,305.10 0.8 UPM-Kymmene Oyj 5,956,283.07 0.7 Deutsche Post AG 5,851,177.11 0.7 Enel SpA 5,808,234.13 0.7 AXA SA 5,790,969.55 0.7 Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Is the Cac 40 Responsible?

IS THE CAC 40 RESPONSIBLE? ENGAGEMENT REPORT ANNUAL GENERAL MEETINGS 2020 MORE EFFORTS TO BE MADE Faced with the challenges of our time – climate change, the collapse of biodiversity, the global growth in inequality – the social responsibility of companies and investors is considerable. Responsible investors have a role to play in engaging in a constructive dialogue with companies on key issues that affect their future as well as that of their stakeholders. For this reason, in 2020, the FIR launched its first campaign of written questions, which were submitted to the general meetings of CAC 40 companies. Large companies not only have an impact on the economy but also on the environment and on the social equilibrium of the countries in which they operate. The FIR has therefore chosen to conduct this campaign with the CAC 40 by acquiring one share of each company on the CAC 40. While the FIR’s stock portfolio remains modest, the members of its “Dialogue and Engagement Commission” manage over €4,500 billion in assets, which is somewhat less so. In this campaign, which included 12 questions1 on 12 major social responsibility themes, our assessments were guided by the quality of the response and the seriousness with which companies answered. Although our analyses of the responses are necessarily subjective to a certain extent, this report is based on meticulous work carried out by a group of ESG analysis professionals, based on a detailed and shared analysis grid. We can say straight away that the answers we received did not live up to our expectations. -

Dnca Invest Eurose F L E X I B L E a S S E T

Promotional document | Monthly management report | August 2021 | A Share DNCA INVEST EUROSE F L E X I B L E A S S E T Investment objective Performance (from 31/08/2011 to 31/08/2021) The Sub-Fund seeks to outperform the DNCA INVEST EUROSE (A Share) Cumulative performance Reference Index(1) 80% FTSE MTS Global + 20% EURO 180 STOXX 50 Net Return composite index calculated with dividends reinvested, over +69.71% the recommended investment period (3 years). 160 Financial characteristics +41.96% NAV (€) 163.77 140 Net assets (€M) 2,411 Number of equities holdings 33 Number of issuers 147 120 e Dividend yield 2020 3.59% ND/EBITDA 2020 1.6x Price to Book 2020 1.2x 100 Price Earning Ratio 2021e 11.4x EV/EBITDA 2021e 5.6x Price to Cash-Flow 2021e 5.7x Average modified duration 2.21 80 Aug-11 Aug-13 Aug-15 Aug-17 Aug-19 Aug-21 Average maturity (years) 2.55 Average yield 0.64% (1)80% FTSE MTS Global + 20% EURO STOXX 50 NR. Past performance is not a guarantee of future Average rating BB+ performance. Annualised performances and volatilities (%) Since 1 year 3 years 5 years 10 years inception A Share +11.27 +1.37 +2.04 +3.57 +3.61 Reference Index +6.45 +5.24 +3.37 +5.43 +4.36 A Share - volatility 5.19 7.06 5.92 5.52 4.91 Reference Index - volatility 3.94 5.45 4.86 5.31 5.47 Cumulative performances (%) Since 1 month YTD 1 year 3 years 5 years 10 years inception A Share +1.01 +5.83 +11.27 +4.17 +10.60 +41.96 +63.77 Reference Index +0.06 +2.35 +6.45 +16.56 +18.01 +69.72 +81.24 Calendar year performances (%) 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016 A Share -4.27 +7.85 -

PR Successful Sale of Alstom Shares by Bouygues

PRESS RELEASE BOUYGUES SUCCESSFULLY COMPLETES SALE OF ALSTOM SHARES PARIS 02/06/2021 Not for distribution, directly or indirectly, in Canada, Australia or Japan Bouygues S.A. (“Bouygues”) announces the successful sale of 11,000,000 shares in Alstom S.A. (“Alstom”), representing 2.96% of Alstom share capital, at a price of 45.35 euros per share (i.e., a total amount of 499 million euros) in an accelerated bookbuilt offering to qualified investors (the “Offering”). Following the Offering, Bouygues will retain 0.16% of Alstom share capital. BNP PARIBAS and J.P. Morgan acted as Joint Global Coordinators and Joint Bookrunners, and BofA Securities, Crédit Agricole CIB and Société Générale acted as Joint Bookrunnners of the Offering. Rothschild & Co and Perella Weinberg Partners acted as financial advisers to Bouygues. Alstom shares are listed on the regulated market of Euronext in Paris (ISIN code: FR0010220475). DISCLAIMER This press release is for information purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or subscribe any securities and does not constitute a public offer other than the offering to qualified investors in any jurisdiction, including France. The sale of the Alstom shares does not constitute a public offer other than the offering to qualified investors only, including in France. No communication and no information in respect of the sale by Bouygues of Alstom shares may be distributed to the public in any jurisdiction where a registration or approval is required. No steps have been or will be taken in any jurisdiction where such steps would be required. -

Moving from Compliance to Responsibility

CORPORATE TAX PRACTICES: MOVING FROM COMPLIANCE TO RESPONSIBILITY CAC 40 ENGAGEMENT REPORT CONTENTS PART 1 Corporate Tax Responsibility: context and issues _____Pages 2 - 4 Tax responsibility, an integral part of Corporate Social Responsibility Corporate tax practices: what are the issues for responsible investors? An increasingly demanding regulatory and legislative framework for tax transparency PART 2 Methodology and main lessons from the FIR campaign _____Pages 5 - 7 Methodology and implementation of the FIR’s Dialogue and Engagement campaign: a preliminary consultation on the tax practices of CAC 40 groups • Letter addressed to the Chairmen of CAC 40 companies • FIR questionnaire • Level of participation of CAC 40 companies in the FIR consultation • Significant mobilisation, but responses of varying quality The FIR’s findings and recommendations on tax responsibility • Unclear tax policies, where compliance prevails over responsibility • The FIR’s recommendations for fiscal citizenship PART 3 Detailed analysis of responses to the FIR questionnaire _____Pages 8 - 13 Level of company participation Hierarchical level and quality of responses Lessons from the survey APPENDICES Additional Resources _____Pages 14 - 17 FOREWORD TAX RESPONSIBILITY OF CAC 40 COMPANIES: a Dialogue and Engagement campaign led by the French Social Investment Forum (Forum pour l’Investissement Responsable, FIR) “Companies benefit from the quality of education and research, and from the infrastructures, institutions and healthcare systems of the countries in which they operate. Their contribution to the public finances of these countries is therefore part of the social contract. It is a mutually beneficial social choice. This is why the FIR, through its engagement, aims to remind companies that fiscal citizenship is an integral part of corporate social responsibility and to encourage them to adopt best practices.“ Alexis Masse, President of the FIR. -

Senior Executive Appointments at Bouygues Immobilier, Colas and Bouygues Telecom

PRESS RELEASE SENIOR EXECUTIVE APPOINTMENTS AT BOUYGUES IMMOBILIER, PARIS COLAS AND BOUYGUES TELECOM 18/02/2021 The Board of Bouygues Immobilier, and the Boards of Directors of Bouygues Telecom and Colas have announced a number of senior executive appointments. The Board of Bouygues Immobilier met on 11 February 2021 to appoint Bernard Mounier Chairman of Bouygues Immobilier as of 19 February 2021. He succeeds Pascal Minault, Chairman since February 2019, who is joining Bouygues Construction alongside Philippe Bonnave in order to prepare to succeed him as Chairman and CEO. Bernard Mounier joins the Bouygues Group Management Committee. Bernard Mounier, 62, joined the Bouygues group in 1983 as a works supervisor. After holding various operational and executive positions within Bouygues Construction in the Paris region, he was appointed Chairman of Bouygues Bâtiment Ile-de-France in 2015. On 1 September 2018 he was appointed Deputy CEO of Bouygues Construction with responsibility for Bouygues Bâtiment France-Europe and Purchasing policy. He was also a member of Bouygues Construction’s Executive Committee. ©Jean Chiscano ©Jean Chiscano At its meeting of 15 February 2021, the Board of Directors of Bouygues Telecom decided to combine the functions of Chairman and Chief Executive Officer. Richard Viel has thus been appointed Chairman and CEO of Bouygues Telecom. He had been Chief Executive Officer since 2018. Olivier Roussat, CEO of the Bouygues group, has therefore resigned from office as Chairman of Bouygues Telecom. Richard Viel, 63, is a graduate of Ecole Supérieure d’Ingénieurs en Génie Électrique and INSEAD. He began his career at Dassault Électronique as an engineer before being appointed head of sales and marketing. -

FACTSHEET - AS of 28-Sep-2021 Solactive Mittelstand & Midcap Deutschland Index (TRN)

FACTSHEET - AS OF 28-Sep-2021 Solactive Mittelstand & MidCap Deutschland Index (TRN) DESCRIPTION The Index reflects the net total return performance of 70 medium/smaller capitalisation companies incorporated in Germany. Weights are based on free float market capitalisation and are increased if significant holdings in a company can be attributed to currentmgmtor company founders. HISTORICAL PERFORMANCE 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 Jan-2010 Jan-2012 Jan-2014 Jan-2016 Jan-2018 Jan-2020 Jan-2022 Solactive Mittelstand & MidCap Deutschland Index (TRN) CHARACTERISTICS ISIN / WKN DE000SLA1MN9 / SLA1MN Base Value / Base Date 100 Points / 19.09.2008 Bloomberg / Reuters MTTLSTRN Index / .MTTLSTRN Last Price 342.52 Index Calculator Solactive AG Dividends Included (Performance Index) Index Type Equity Calculation 08:00am to 06:00pm (CET), every 15 seconds Index Currency EUR History Available daily back to 19.09.2008 Index Members 70 FACTSHEET - AS OF 28-Sep-2021 Solactive Mittelstand & MidCap Deutschland Index (TRN) STATISTICS 30D 90D 180D 360D YTD Since Inception Performance -3.69% 3.12% 7.26% 27.72% 12.73% 242.52% Performance (p.a.) - - - - - 9.91% Volatility (p.a.) 13.05% 12.12% 12.48% 13.60% 12.90% 21.43% High 357.49 357.49 357.49 357.49 357.49 357.49 Low 342.52 329.86 315.93 251.01 305.77 52.12 Sharpe Ratio -2.77 1.14 1.27 2.11 1.40 0.49 Max. Drawdown -4.19% -4.19% -4.19% -9.62% -5.56% -47.88% VaR 95 \ 99 -21.5% \ -35.8% -34.5% \ -64.0% CVaR 95 \ 99 -31.5% \ -46.8% -53.5% \ -89.0% COMPOSITION BY CURRENCIES COMPOSITION BY COUNTRIES EUR 100.0% DE -

Global Equity Fund Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP

Global Equity Fund June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP 2.5289% 2.5289% APPLE INC 2.4756% 2.4756% AMAZON COM INC 1.9411% 1.9411% FACEBOOK CLASS A INC 0.9048% 0.9048% ALPHABET INC CLASS A 0.7033% 0.7033% ALPHABET INC CLASS C 0.6978% 0.6978% ALIBABA GROUP HOLDING ADR REPRESEN 0.6724% 0.6724% JOHNSON & JOHNSON 0.6151% 0.6151% TENCENT HOLDINGS LTD 0.6124% 0.6124% BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC CLASS B 0.5765% 0.5765% NESTLE SA 0.5428% 0.5428% VISA INC CLASS A 0.5408% 0.5408% PROCTER & GAMBLE 0.4838% 0.4838% JPMORGAN CHASE & CO 0.4730% 0.4730% UNITEDHEALTH GROUP INC 0.4619% 0.4619% ISHARES RUSSELL 3000 ETF 0.4525% 0.4525% HOME DEPOT INC 0.4463% 0.4463% TAIWAN SEMICONDUCTOR MANUFACTURING 0.4337% 0.4337% MASTERCARD INC CLASS A 0.4325% 0.4325% INTEL CORPORATION CORP 0.4207% 0.4207% SHORT-TERM INVESTMENT FUND 0.4158% 0.4158% ROCHE HOLDING PAR AG 0.4017% 0.4017% VERIZON COMMUNICATIONS INC 0.3792% 0.3792% NVIDIA CORP 0.3721% 0.3721% AT&T INC 0.3583% 0.3583% SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS LTD 0.3483% 0.3483% ADOBE INC 0.3473% 0.3473% PAYPAL HOLDINGS INC 0.3395% 0.3395% WALT DISNEY 0.3342% 0.3342% CISCO SYSTEMS INC 0.3283% 0.3283% MERCK & CO INC 0.3242% 0.3242% NETFLIX INC 0.3213% 0.3213% EXXON MOBIL CORP 0.3138% 0.3138% NOVARTIS AG 0.3084% 0.3084% BANK OF AMERICA CORP 0.3046% 0.3046% PEPSICO INC 0.3036% 0.3036% PFIZER INC 0.3020% 0.3020% COMCAST CORP CLASS A 0.2929% 0.2929% COCA-COLA 0.2872% 0.2872% ABBVIE INC 0.2870% 0.2870% CHEVRON CORP 0.2767% 0.2767% WALMART INC 0.2767%