1A123 Systems, Inc., Is Named Separately As a Defendant, but the Case Against It Was Automatically Stayed When the Company Filed for Bankruptcy Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Million Electric Vehicles by 2015

One Million Electric Vehicles By 2015 February 2011 Status Report 1 Executive Summary President Obama’s goal of putting one million electric vehicles on the road by 2015 represents a key milestone toward dramatically reducing dependence on oil and ensuring that America leads in the growing electric vehicle manufacturing industry. Although the goal is ambitious, key steps already taken and further steps proposed indicate the goal is achievable. Indeed, leading vehicle manufacturers already have plans for cumulative U.S. production capacity of more than 1.2 million electric vehicles by 2015, according to public announcements and news reports. While it appears that the goal is within reach in terms of production capacity, initial costs and lack of familiarity with the technology could be barriers. For that reason, President Obama has proposed steps to accelerate America’s leadership in electric vehicle deployment, including improvements to existing consumer tax credits, programs to help cities prepare for growing demand for electric vehicles and strong support for research and development. Introduction In his 2011 State of the Union address, President Obama called for putting one million electric vehicles on the road by 2015 – affirming and highlighting a goal aimed at building U.S. leadership in technologies that reduce our dependence on oil.1 Electric vehicles (“EVs”) – a term that includes plug-in hybrids, extended range electric vehicles and all- electric vehicles -- represent a key pathway for reducing petroleum dependence, enhancing environmental stewardship and promoting transportation sustainability, while creating high quality jobs and economic growth. To achieve these benefits and reach the goal, President Obama has proposed a new effort that supports advanced technology vehicle adoption through improvements to tax credits in current law, investments in R&D and competitive “With more research and incentives, programs to encourage communities to invest we can break our dependence on oil in infrastructure supporting these vehicles. -

Form 10-K Altair Nanotechnologies Inc

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K [X] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2011 [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM _________ TO ___________ ALTAIR NANOTECHNOLOGIES INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Canada 1-12497 33-1084375 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission File No.) (IRS Employer of incorporation) Identification No.) 204 Edison Way Reno, Nevada 89502-2306 (Address of principal executive offices, including zip code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (775) 856-2500 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Common Shares, no par value NASDAQ Capital Market (Title of Class) (Name of each exchange on which registered) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. YES [ ] NO [X ] Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. YES [ ] NO [X ] Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Review of ELV Exemption 5 from the View of Lithium-Ion Battery Makers and Experts

A123 Systems LLC, Fraunhofer ICT, LG Chem Ltd., and Samsung SDI Co. Ltd. Review of ELV Exemption 5 From the view of lithium-ion battery makers and experts 2014-December-17 Question 1: Please explain whether the use of lead in the application addressed under Exemption 5 of the ELV Directive is still unavoidable so that Art. 4(2)(b)(ii) of the ELV Directive would justify the continuation of the exemption. Please clarify what types of vehicles your answer refers to, i.e., conventional vehicles and various types of hybrid and electric vehicles and which functionalities are covered (starting, ignition, lighting and other points of consumption). The use of lead in batteries is potentially avoidable and definitely reducible in most conventional passenger vehicles by the adoption of emerging energy storage technologies. 12V lithium-ion batteries are in fact already in series production for automotive OEMs in Europe and across the world and are projected to increase in volume over the next decade mostly due to regulatory drivers related to vehicle emissions reduction. The European Commission has set emissions targets [European Commission, http://ec.europa.eu/environment/air/transport/road.htm , as of 28 Oct 2014] for which major fuel saving technologies are required. Hybrid and electric vehicles have received the most attention for yielding aggressive improvement in emissions. However consumer adoption rates of these vehicle types have been slow and therefore automakers have been forced to identify other fuel saving technologies that have less impact on the consumer and are more economically viable across the vehicle portfolio. A new, smaller form of vehicle electrification called the micro-hybrid is expected to fill this gap. -

Electric Drive in America Market Overview

Advancing the Deployment of Electric Vehicles: Market and Policy Outlook for Electrifying Transportation Genevieve Cullen, Vice President, EDTA December 6, 2011 Market Outlook • Late 2010, GM Volt & Nissan Leaf first mass-market plug-in electric vehicles • ~ 20 plug-in EV models expected by the end of 2012, including plug- in Prius hybrid, battery electric Ford Focus • National and regional charging infrastructure beings installed rapidly. Projected cumulative investment of $5-10 billion by 2015 Sales • The total number of plug-in vehicles (including plug-in hybrids and battery EVs) sold in August 2012 was 4,715. – OVER PREVIOUS MONTH: 56.3% increase • 3,016 sold in July 2012. – OVER THIS MONTH LAST YEAR: 183.2% increase • 1,665 sold in August 2011. • There have been 25,290 total plug-ins (including plug-in hybrids and battery EVs) sold in 2012. This is a 170.5% increase over this time last year. Vehicles Available Now Battery Electric Vehicles Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles AMP Mle BMW Hydrogen 7* Coda Sedan Honda FCX Clarity* Ford Transit Connect Electric Mercedes-Benz B-Class* Ford Focus BEV Honda Fit EV Mitsubishi i-MiEV Nissan LEAF Smart fortwo EV Tesla Model S Plug-In Hybrids Chevrolet Volt Fisker Karma Toyota Prius Plug-In Hybrid Via Motors Vtrux Updated October 1, 2012 * Limited R Vehicles Available Now Hybrid Electric Vehicles Lexus CT 200h Acura ILX Lexus HS 250h BMW ActiveHybrid 7L Lexus LS 600h L Buick Regal eAssist Lexus RX 450h Cadillac Escalade Hybrid Lincoln MKZ Hybrid Chevrolet Malibu Hybrid Mercedes-Benz ML450 Hybrid Chevrolet -

Contact: Jonathan Michaels for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Phone: (949) 581-6900 Email: [email protected]

Contact: Jonathan Michaels FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Phone: (949) 581-6900 Email: [email protected] HENRIK FISKER FILES $100 MILLION LAWSUIT AGAINST ASTON MARTIN FOR EXTORTION Newport Beach, California (January 5, 2016) – Legendary automobile designer Henrik Fisker has filed a $100 million lawsuit against automaker Aston Martin for civil extortion related to Aston Martin’s threats regarding the introduction of Fisker’s “Force 1” at the acclaimed Detroit Auto Show later this month. The suit was filed in U.S. Federal Court, Central District of California, by Fisker’s legal counsel, Jonathan A. Michaels of MLG Automotive Law, an acclaimed attorney specializing in automobile law. The suit follows a threatening letter from Aston Martin to Fisker sent in late December demanding that he not launch the Force 1 at the Detroit Auto Show, or that he first make changes to his design before its launch. Aston Martin's demand was made solely on a ‘teaser’ sketch of the automobile Fisker released to the media in December to invite media to its launch at the 2016 NAIAS show. Ironically, Aston Martin’s letter admits, “We do not know what the final version of Fisker’s Force 1 will look like.” “This is a classic case of David vs. Goliath,” said Fisker. “Aston Martin is trying to intimidate me to prop up their own flailing company and to mask their financial and product deficiencies. I refuse to be intimidated and that is the reason for today’s filing.” “We believe that in an effort to protect itself from further market erosion, Aston Martin and their three executives who run the company, conspired and devised a scheme to stomp out Henrik Fisker’s competitive presence in the luxury sports car industry,” explained Michaels. -

Seehotcars.Com 1 OYSTER PERPETUAL SKY-DWELLER

2014 SeeHotCars.com 1 OYSTER PERPETUAL SKY-DWELLER Welcome to Concours du Soleil 2014 Here we are again together for the most exciting event of the fall season in Albuquerque, Concours du Soleil! We welcome you to our 8th annual show organized for one simple reason...to raise funds for our community. This show would not be possible without 1. Car owners who generously share their beloved automobile(s). They are the heart of our show and some of the finest people you will meet. 2. Sponsors and major contributors. Please support the businesses you see in this program, corporate generosity is the backbone of a thriving community. 3. Albuquerque Community Foundation-asked to become the organizers of Concours 8 years ago, the staff continues to design an event every year that becomes the talk of the town while raising funds for local nonprofit organizations. Watch SeeHotCars.com for the announcement of this year’s grant distributions. Thank you for your continued generosity. Jerry Roehl, Steve Maestas, Kevin Yearout, Jason Harrington, Mark Gorham —The Cinco Amigos rolex oyster perpetual and sky-dweller are trademarks. 3 2 3 Creative Partnerships Reap the Past Winners Best Reward for our Community. best of show people’s choice winners winners 100% of the proceeds from this weekend’s events will benefit our community Now & Forever. A portion will be added to the Cinco Amigos permanent fund of the Albuquerque Community Foundation. The rest will be granted to local 2007 2007 nonprofit organizations. 1929 Duesenberg SJ Murphy 2005 Lamborghini Convertible Coupe Murcielago Roadster Since this partnership began, Concours du Soleil has raised over $500,000. -

Batteries for Electric and Hybrid Heavy Duty Vehicles

Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products of manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. The mention of commercial products, their use in connection with material reported herein is not to be construed as actual or implied endorsement of such products by U.S. Department of Transportation or the contractor. For questions or copies please contact: CALSTART 48 S Chester Ave. Pasadena, CA 91106 Tel: (626) 744 5600 www.calstart.org Energy Storage Compendium: Batteries for Electric and Hybrid Heavy Duty Vehicles March 2010 CALSTART Prepared for: U.S. Department of Transportation Abstract The need for energy storage solutions and technologies is growing in support of the electrification in transportation and interest in hybrid‐electric and all electric heavy‐duty vehicles in transit and the commercial vehicles. The main purpose of this document is to provide an overview of advanced battery energy storage technologies available currently or in development for heavy‐duty, bus and truck, applications. The same set of parameters, such as energy density, power density, lifecycle and weight were used in review of the specific battery technology solution. The important performance requirements for energy storage solutions from the vehicle perspective were reviewed and the basic advantages of different cell chemistries for vehicle batteries were summarized. A list of current battery technologies available for automotive applications is provided. -

Danish Week Flier V

feature event: An evening with: “The New Age of Emotional Design” HENRIK FISKER entrepreneur and leading automotive designer. Creator of iconic cars such as BMW Z8, Aston Martin DB9, Aston Martin V8 Vantage, Fisker Karma, Rocket and more recently Destino V8 and Force 1. One or more of these cars may be on display at event. Tuesday, September 13, 6:30-9pm. Cross Campus, 929 Colorado Ave, Santa Monica Program: 6:30pm Doors open 7:00pm Entertainment by Sascha Dupont 7:45pm Presentation/interview with Henrik Fisker (interview by Morten Bay, journalist & author) Refreshments: Appetizers, wine, beer, coffee Registration: $20 with advance registration. DACC business members free. Event co-sponsor: SIGN UP: www.daccsocal.com/henrikfisker Award-winning Danish Songwriter & pianist/vocalist Sascha Dupont \ Danish week sponsors: Sep. 10 Sat DanishWeek Launch Coffee and Lecture with Danish family therapist Susi Rasmussen: Drop opdragelsen og bliv bedre forældre! Danish Cultural Center. Yorba Linda. 10-12noon. Contact [email protected] Sep. 11 Sun Service and Danish breakfast at Danish Church Yorba Linda. 11am. Contact [email protected] House of Denmark in San Diego. Open house noon-4pm. www.HouseofDenmark.org Sep. 13 Tue feature event: An evening with entrepreneur and leading automotive designer Henrik Fisker: “The New Age of Emotional Design” Entertainment by: Danish Award-winning songwriter and pianist/vocalist Sascha Dupont. Cross Campus, 929 Colorado Ave, Santa Monica. 6.30-9.30pm. SIGN UP: www.daccsocal.com/henrikfisker Sep. 15 Thu Danish Art and Design exhibit by Hanne Støvring. Lighting by Louis Poulsen and in partnership with American Friends of Statens Museum for Kunst. -

15.905 – Technology Strategy: Final Paper Strategic Analysis And

15.905 – Technology Strategy: Final Paper Strategic Analysis and Recommendations Team 12 – Jorge Amador, John Kluza, Yulia Surya May 13th, 2008 Background A123Systems is a Lithium-Ion battery producer known for its nanophospate technology licensed from MIT. Within the seven years since it’s founded, the company has received global recognition for its superior battery characteristics compared to the widely-used Li-Ion Cobalt Cathode technology. It is also known as one of the companies who is revolutionizing the integration of Li-Ion into automotive applications. The company has secured more than $100M in venture capital and multiple mega deals with large clients, ranging from automotive to aviation. However, given the dynamic nature of this relatively new technology, especially in automotive niche, sustaining the success of such a company requires thorough analysis, well-defined strategy and excellent execution. This paper will provide a set of recommendations for A123Systems’ short-term and long-term strategies, using the company’s current business and its presence in the overall domain and industry as building blocks. Company & Industry Profile Domain A123Systems is a relatively new player in the rechargeable power source domain, particularly in the lithium-based batteries industry. In this domain, Lithium-Ion has been mostly known for its applications in consumer electronics. However, technological breakthroughs in this domain are shifting this trend. Lithium-Polymer is slowly taking over the consumer electronics space, while Li-Ion starts to gain momentum in the automotive and other high-powered applications. A123Systems is one of the companies that introduced revolutionary technologies which allow wider applicability of lithium-ion. -

Business Report the Chronicle With

BLOOMBERG BRIEFING Number of the day Hear here “Guys say, ‘Gee, I think that Pinterest is only for women. I want to go where there are people like me.’ ” John Manoogian III, co-founder of social $2.5 million advertising firm 140 Proof, on male-oriented image-sharing sites like MANteresting, Du- That’s how much the Finnish mo- depins, PunchPin, Gentlemint and Dart- bile-game developer Supercell is itup. Pinterest is the third-largest social Paul Sakuma / Associated Press 2008 generating in sales of virtual goods network after Facebook and Twitter, with every day. The startup rolled out 40 million users — mostly women — and lots Heads up two popular titles last summer, the of imitators. While it focuses on fashion, Electronic Arts reports quarterly earnings on medieval tower-defense game fingernail art and rainbow fruit kabobs, MAN- Tuesday, and analysts expect net income to drop "Clash of Clans" and the crop- teresting leans toward muscle cars, WD-40 31 percent to $275 million from a year earlier. Sales tending "Hay Day." Both free apps and bacon pancakes. Story on page D2. may slip 24 percent to $1.04 billion. The Redwood feature vivid graphics and addictive City company is restructuring to focus on mobile play, attracting a combined 8.5 Supercell games while still developing titles for a new gener- million registered users and putting The free app “Clash of ation of consoles. Last month EA said it was cut- the pair at the top of Apple’s iOS Clans” is at the top of Bloomberg Market Report ting jobs and would shut down three games devel- game charts since December. -

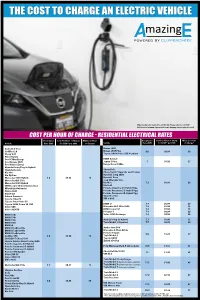

Cost Per Hour of Charge

THE COST TO CHARGE AN ELECTRIC VEHICLE POWERED BY Older model cars may not be on this list. Please refer to our EVSE Selector tool at www.clippercreek.com/charging-station-selector-tool/ COST PER HOUR OF CHARGE - RESIDENTIAL ELECTRICAL RATES Acceptance Cost Per Hour of Charge Miles per Hour Acceptance Cost Per Hour of Charge Miles per Hour Vehicle Rate (kW) $0.1269** per kWh of Charge* Vehicle Rate (kW) $0.1269** per kWh of Charge* Audi A3 E-Tron Nissan LEAF Cadillac ELR Nissan LEAF Plus 6.6 $0.84 26 Chevy Volt Toyota RAV4 Prime XSE Premium Fisker Karma Ford C Max Energi BMW ActiveE Ford Escape 2020 Jaguar I-Pace 7 $0.89 27 Ford Fusion Energi Range Rover P400e Hyundai Ioniq Plug-In Hybrid Hyundai Sonata Chevy Bolt Kia Niro Chevy Volt LT Upgrade and Premier Kia Optima Hyundai Ioniq 2020 Mercedes C350 Hybrid 3.3 $0.42 13 Hyundai Kona Mercedes GLE 550e Jeep Wrangler 4xe Mercedes S550 Hybrid Kia Niro 7.2 $0.91 28 MINI Cooper S E Countryman ALL4 Kia Soul Mitsubishi Outlander Porsche Cayenne S E-Hybrid Upg Nissan LEAF Porsche Panamera S E-Hybrid Upg Smart Car Porsche Panamera 4 E-Hybrid Upg Subaru Crosstrek Smart ForTwo Toyota Prius EV VW e-Golf Toyota Prius Prime EV Toyota RAV4 Prime SE, XSE BMW i3 7.4 $0.94 29 Volvo V60 Mercedes GLC 350e 2020 7.4 $0.94 13 Volvo XC90T8 MINI Cooper SE 7.4 $0.94 13 Polestar 2 7.4 $0.94 29 BMW 330e Volvo XC40 Recharge 7.4 $0.94 29 BMW 530e BMW 740e Audi Q5 Plug-In Hybrid 7.7 $0.98 11 BMW 745e Tesla Model 3 Standard 7.7 $0.98 30 BMW i8 BMW X3 xDrive30e Audi e-tron SUV BMW X5 xDrive40e Mercedes B Class B250e Porsche -

Chinese Rescue of Battery Maker Saves U.S. Jobs, CEO Says: Cars

Chinese Rescue of Battery Maker Saves U.S. Jobs, CEO Says: Cars 2012-08-09 23:43:51.607 GMT By Alan Ohnsman and Hasan Dudar Aug. 10 (Bloomberg) -- A123 Systems Inc.’s chief executive officer said the company’s financial rescue by China’s largest auto-parts maker will preserve U.S. jobs, after the agreement drew criticism from congressional Republicans. A123, a maker of lithium-ion batteries for electric cars, may get financing worth as much as $450 million from Wanxiang Group Corp. The deal that may give Wanxiang an 80 percent stake in Waltham, Massachusetts-based A123, recipient of a $249 million federal grant for U.S. factory construction, is opposed by Representative Cliff Stearns, a Florida Republican. The federal funds “can only be used for building factories in North America and the creation of jobs, and that’s what’s been done,” David Vieau, A123’s president and CEO, said in a telephone interview yesterday. “This is a step toward financing the company so we can continue on that mission.” The possibility of A123 being bought by a Chinese company fuels further political debate over government financing of alternative-energy and transportation businesses. Federal grants and loans to companies including A123, Fisker Automotive Inc. and Tesla Motors Inc. have drawn scrutiny from congressional Republicans following the September 2011 bankruptcy filing of solar-panel maker Solyndra LLC two years after getting a $535 million loan guarantee from the U.S. Energy Department. Stearns, author of a pending bill intended to prevent more situations like Solyndra’s, said this week that A123’s financing arrangement with Wanxiang raises possible security concerns.