Hauser the Explorer by Terry White and Meg Costello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Energy Facilities Siting Board

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS ENERGY FACILITIES SITING BOARD ) Petition of Vineyard Wind LLC Pursuant to G.L. c. ) 164, § 69J for Approval to Construct, Operate, and ) Maintain Transmission Facilities in Massachusetts ) for the Delivery of Energy from an Offshore Wind ) EFSB 20-01 Energy Facility Located in Federal Waters to an ) NSTAR Electric (d/b/a Eversource Energy) ) Substation Located in the Town of Barnstable, ) Massachusetts. ) ) ) Petition of Vineyard Wind LLC Pursuant to G.L. c. ) 40A, § 3 for Exemptions from the Operation of the ) Zoning Ordinance of the Town of Barnstable for ) the Construction and Operation of New Transmission Facilities for the Delivery of Energy ) D.P.U. 20-56 from an Offshore Wind Energy Facility Located in ) Federal Waters to an NSTAR Electric (d/b/a. ) Eversource Energy) Substation Located in the ) Town of Barnstable, Massachusetts. ) ) ) Petition of Vineyard Wind LLC Pursuant to G.L. c. ) 164, § 72 for Approval to Construct, Operate, and ) Maintain Transmission Lines in Massachusetts for ) the Delivery of Energy from an Offshore Wind ) D.P.U 20-57 Energy Facility Located in Federal Waters to an ) NSTAR Electric (d/b/a Eversource Energy) ) Substation Located in the Town of Barnstable, ) Massachusetts. ) ) AFFIDAVIT OF AARON LANG I, Aaron Lang, Esq., do depose and state as follows: 1. I make this affidavit of my own personal knowledge. 2. I am an attorney at Foley Hoag LLP, counsel for Vineyard Wind LLC (“Vineyard Wind”) in this proceeding before the Energy Facilities Siting Board. 3. On September 16, 2020, the Presiding Officer issued a letter to Vineyard Wind containing translation, publication, posting, and service requirements for the Notice of Adjudication and Public Comment Hearing (“Notice”) and the Notice of Public Comment Hearing Please Read Document (“Please Read Document”) in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Fishery Circular

'^y'-'^.^y -^..;,^ :-<> ii^-A ^"^m^:: . .. i I ecnnicai Heport NMFS Circular Marine Flora and Fauna of the Northeastern United States. Copepoda: Harpacticoida Bruce C.Coull March 1977 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA TECHNICAL REPORTS National Marine Fisheries Service, Circulars The major respnnsibilities of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) are to monitor and assess the abundance and geographic distribution of fishery resources, to understand and predict fluctuationsin the quantity and distribution of these resources, and to establish levels for optimum use of the resources. NMFS is also charged with the development and implementation of policies for managing national fishing grounds, development and enforcement of domestic fisheries regulations, surveillance of foreign fishing off United States coastal waters, and the development and enforcement of international fishery agreements and policies. NMFS also assists the fishing industry through marketing service and economic analysis programs, and mortgage insurance and vessel construction subsidies. It collects, analyzes, and publishes statistics on various phases of the industry. The NOAA Technical Report NMFS Circular series continues a series that has been in existence since 1941. The Circulars are technical publications of general interest intended to aid conservation and management. Publications that review in considerable detail and at a high technical level certain broad areas of research appear in this series. Technical papers originating in economics studies and from management in- vestigations appear in the Circular series. NOAA Technical Report NMFS Circulars arc available free in limited numbers to governmental agencies, both Federal and State. They are also available in exchange for other scientific and technical publications in the marine sciences. -

Scott M. Melvin Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Field Headquarters, Rt

STATUS OF PIPING PLOVERS IN MASSACHUSETTS - 1992 SUMMARY Scott M. Melvin Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Field Headquarters, Rt. 135 Westborough, MA 01581 Observers reported a total of 213 breeding pairs of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) at 58 sites in Massachusetts in 1992 (Table 1) . Breeding pairs are defined as pairs observed with either a nest or unfledged chicks or that exhibit site tenacity and evidence of pair bonding and territoriality. Observer effort in 1992, measured as number of sites surveyed and intensity of census effort at each site, was roughly comparable to previous efforts since 1986. In at least 2 instances, pairs that nested unsuccessfully were believed to have moved to new sites and renested. These pairs were included in counts of pairs at both sites where they nested, but were counted only once in the overall state total (Table 1). Also not included in the state total were 2 birds seen for only 3 days at fisbury Great Pond on Martha's Vineyard, and a single bird that was present at Cockeast Pond in Westport. The 1992 total of 213 pairs is the highest count of Piping Plovers recorded in Massachusetts since comprehensive statewide surveys began in 1985, and represents an increase of 53 pairs over the 1991 count of 160 pairs (Table 2). Numbers increased in 6 bf 7 regions of the state; only Martha's Vineyard/Elizabeth Islands decreased by 1 pair. The largest increases came on the Lower Cape (from 50 to 84 pairs in 1991 vs. 1992) and the Upper Cape (from 21 to 32 pairs). -

Edward Kennedy

AAmmeerriiccaannRRhheettoorriicc..ccoomm Edward Kennedy Chappaquiddick Address to the People of Massachusetts Broadcast 29 July 1969 AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio My fellow citizens: I have requested this opportunity to talk to the people of Massachusetts about the tragedy which happened last Friday evening. This morning I entered a plea of guilty to the charge of leaving the scene of an accident. Prior to my appearance in court it would have been [im]proper for me to comment on these matters. But tonight I am free to tell you what happened and to say what it means to me. On the weekend of July 18th, I was on Martha's Vineyard Island participating with my nephew, Joe Kennedy -- as for thirty years my family has participated -- in the annual Edgartown Sailing Regatta. Only reasons of health prevented my wife from accompanying me. On Chappaquiddick Island, off Martha's Vineyard, I attended, on Friday evening, July 18th, a cook-out I had encouraged and helped sponsor for a devoted group of Kennedy campaign secretaries. When I left the party, around 11:15pm, I was accompanied by one of these girls, Miss Mary Jo Kopechne. Mary Jo was one of the most devoted members of the staff of Senator Robert Kennedy. She worked for him for four years and was broken up over his death. For this reason, and because she was such a gentle, kind, and idealistic person, all of us tried to help her feel that she still had a home with the Kennedy family. Transcription updated 2018 by Michael E. -

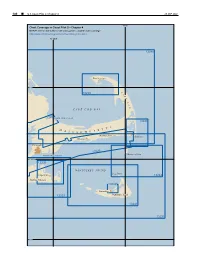

Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound

186 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 26 SEP 2021 70°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 4 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 70°30'W 13246 Provincetown 42°N C 13249 A P E C O D CAPE COD BAY 13229 CAPE COD CANAL 13248 T S M E T A S S A C H U S Harwich Port Chatham Hyannis Falmouth 13229 Monomoy Point VINEYARD SOUND 41°30'N 13238 NANTUCKET SOUND Great Point Edgartown 13244 Martha’s Vineyard 13242 Nantucket 13233 Nantucket Island 13241 13237 41°N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 ¢ 187 Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound (1) This chapter describes the outer shore of Cape Cod rapidly, the strength of flood or ebb occurring about 2 and Nantucket Sound including Nantucket Island and the hours later off Nauset Beach Light than off Chatham southern and eastern shores of Martha’s Vineyard. Also Light. described are Nantucket Harbor, Edgartown Harbor and (11) the other numerous fishing and yachting centers along the North Atlantic right whales southern shore of Cape Cod bordering Nantucket Sound. (12) Federally designated critical habitat for the (2) endangered North Atlantic right whale lies within Cape COLREGS Demarcation Lines Cod Bay (See 50 CFR 226.101 and 226.203, chapter 2, (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are for habitat boundary). It is illegal to approach closer than described in 33 CFR 80.135 and 80.145, chapter 2. -

The Chappy Insider's Guide

The Chappy Insider’s Guide 2019 Index Animal Control……………………………………………………………………… 1 Bikes ..…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Car Rentals...……………………………………………………………………… 1 Cemeteries…..……………………………………………………………………. 1 Chappaquiddick Community Center (CCC)…..…………………………… 1 Chappaquiddick Island Association (CIA).…..…………………………………. 2 Chappaquiddick Island Association Open Space Fund……..………….. 2 Chappaquiddick Landing …………..…………………………………………………. 3 Chappy Chat………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Chappy Ferry…………………………………………………………………………………..3 Chappy Kitchen…………………………………………………………………………. 3 Chappy Store aka Jerry’s Place on Chappy………………………………. 3 Code Red.…….……………………………………………………………………. 4 Deer.……….………………………………………….…………………………………… 4 Drivers’ Licenses and Registration ….…………………………………… 4 Driveways……….………………………………………………………………… 4 Emergency.. .…………………………………………………………………… 4 Ferry Service …………………………………………………………………… 5 Fish Delivery ………….…………………………………………………………..……... 6 Fishing…………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Golf………………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Jerry’s Place on Chappy…………………………………………………………………….6 Land Bank………………………………………………………………………… 6 Library…………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Mail & Shipping…………………………………………………………………. 7 Medical…………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Newspapers……………………………………………………………………... 8 Noise and Non-Emergency Issues………………………………………………….. 8 Norton Point Beach………………………………………………………….... 8 Parking at the Point…………………………………………………………... 8 Phone Service…………………………………………………………………… 9 Public Access…………………………………………………………… ……………….. 9 Recycling Center and Refuse -

Analysis of Coastal Erosion on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts: a Paraglacial Island Denise M

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 January 2008 Analysis of Coastal Erosion on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts: a Paraglacial Island Denise M. Brouillette-jacobson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Brouillette-jacobson, Denise M., "Analysis of Coastal Erosion on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts: a aP raglacial Island" (2008). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 176. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/176 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANALYSIS OF COASTAL EROSION ON MARTHA’S VINEYARD, MASSACHUSETTS: A PARAGLACIAL ISLAND A Thesis Presented by DENISE BROUILLETTE-JACOBSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE September 2008 Natural Resources Conservation © Copyright by Denise Brouillette-Jacobson 2008 All Rights Reserved ANALYSIS OF COASTAL EROSION ON MARTHA’S VINEYARD, MASSACHUSETTS: A PARAGLACIAL ISLAND A Thesis Presented by DENISE BROUILLETTE-JACOBSON Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________ John T. Finn, Chair ____________________________________ Robin Harrington, Member ____________________________________ John Gerber, Member __________________________________________ Paul Fisette, Department Head, Department of Natural Resources Conservation DEDICATION All I can think about as I write this dedication to my loved ones is the song by The Shirelles called “Dedicated to the One I Love.” Only in this case there is more than one love. -

Cape Cod, Nantucket, Martha's Vineyard

176 Index Les numéros de page en gras renvoient aux cartes. A Bières 46 Accès 39 Bijoux 124, 153 Acorn Street (Boston) 160 Boardwalk (Sandwich) 68 Activités culturelles 119, 151 Boîtes de nuit 46, 120, 151 Aéroports Boston Athenaeum (Boston) 160 Barnstable Municipal Airport (Cape Cod) 39 Boston Center for the Arts (Boston) 162 Logan Airport (Boston) 39 Boston Common (Boston) 160 Martha’s Vineyard Airport (Martha’s Vineyard) 39 Boston Duck Tours (Boston) 158 Nantucket Memorial Airport (Nantucket) 39 Boston (environs de Cape Cod) 157, 159 Provincetown Municipal Airport (Cape Cod) 39 hébergement 163 T.F. Green Airport (Providence) 39 restaurants 164 Aînés 43 sorties 166 Alimentation 124, 152 Boston Public Library (Boston) 161 Alley’s General Store (West Tisbury) 134 Brant Point Beach (Nantucket) 143 Ambassades 44 Brant Point Lighthouse (Nantucket) 143 American History Museum (Sandwich) 68 Breakers, The (Newport) 169 Antiquités 124 Breakwater Beach (Brewster) 74 Aquinnah (Martha’s Vineyard) 135 Brewster (Cape Cod) 71 Aquinnah Public Beach (Aquinnah) 136 achats 123 Architecture 33 hébergement 98 Argent 44 restaurants 112 Arthur M. Sackler Museum (Cambridge) 163 sorties 120 Brewster Flats (Brewster) 71 Artisanat 124, 153 Art Museum (Sandwich) 68 Brooks Academy Museum (Harwich) 88 Arts 33 Busch-Reisinger Museum (Boston) 163 Arts de la scène 34 Ashumet Holly and Wildlife Sanctuary (Woods Hole) 93 C Assurances 45 Cadeaux 126 Autocar 40 Cahoon Hollow Beach (Wellfleet) 83 Avion 39 Cahoon Museum of American Art (Cotuit) 91 Cambridge (environs de Cape -

Finding of Adverse Effect for the Vineyard Wind 1 Project Construction and Operations Plan Revised November 13, 2020

Finding of Adverse Effect for the Vineyard Wind 1 Project Construction and Operations Plan Revised November 13, 2020 The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has made a Finding of Adverse Effect (Finding) for the Vineyard Wind Construction and Operations Plan (COP) on the Gay Head Light, the Nantucket Island Historic District National Historic Landmark (Nantucket NHL), the Chappaquiddick Island Traditional Cultural Property (Chappaquiddick Island TCP), and submerged ancient landforms that are contributing elements to the Nantucket Sound Traditional Cultural Property (Nantucket Sound TCP), as well as submerged ancient landforms on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) outside the Nantucket Sound TCP, pursuant to 36 CFR 800.5. Resolution of all adverse effects to historic properties will be codified in a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA), pursuant to 36 CFR 800.6(c). 1. Description of the Undertaking On December 19, 2017, BOEM received a COP from Vineyard Wind, LLC (Vineyard Wind) proposing development of an 800-megawatt (MW) offshore wind energy project within Lease OCS-A 0501 offshore Massachusetts. If approved by BOEM, Vineyard Wind would be allowed to construct and operate wind turbine generators (WTGs), an export cable to shore, and associated facilities for a specified term. BOEM is now conducting its environmental and technical reviews of the COP and has published a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) for its decision regarding approval of the plan. BOEM has also published a Supplement to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) to address changes made to the proposed Project design envelope (PDE), as well as to expand its cumulative impact analysis to incorporate additional projects that have been determined to be reasonably foreseeable. -

The Behavioral Ecology and Population Characteristics Of

Antioch University AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses Dissertations & Theses 2016 The Behavioral Ecology and Population Characteristics of Striped Skunks Inhabiting Piper Plover Nesting Beaches on the Island of Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts Luanne Johnson Antioch University, New England Follow this and additional works at: http://aura.antioch.edu/etds Part of the Environmental Studies Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Luanne, "The Behavioral Ecology and Population Characteristics of Striped Skunks Inhabiting Piper Plover Nesting Beaches on the Island of Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts" (2016). Dissertations & Theses. 286. http://aura.antioch.edu/etds/286 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses at AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses by an authorized administrator of AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Department of Environmental Studies DISSERTATION COMM ITTEE PAGE The undersigned have examined the dissertation entitled: THE BEHAVIORAL ECOLOGY AND POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS OF STRIPED SKUNKS INHABITING PIPING PLOVER NESTING BEACHES ON THE ISLAND OF MARTHA’S VINEYARD, MASSACHUSETTS presented by Luanne Johnson candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that it is accepted*. -

Minerals Management Service Documentation of Section 106 Finding of Adverse Effect (Revised)

Minerals Management Service Documentation of Section 106 Finding of Adverse Effect (Revised) Prepared for Submission to Massachusetts Historical Commission Pursuant to 36 CFR 800.6(a)(3) for the Cape Wind Energy Project This report was prepared for the Minerals Management Service (MMS) under contract No. M08-PC-20040 by Ecosystem Management & Associates, Inc. (EM&A). Brandi M. Carrier Jones (EM&A) compiled and edited the report with information provided by the MMS and with contributions from Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. (PAL), National Park Service Determination of Eligibility, as well as by composing original text. Minerals Management Service Documentation of Section 106 Finding of Adverse Effect (Revised) Prepared for Submission to Massachusetts Historical Commission Pursuant to 36 CFR 800.6(a)(3) for the Cape Wind Energy Project Brandi M. Carrier Jones, Compiler and Editor Ecosystem Management & Associates, Inc. REPORT AVAILABILITY Copies of this report can be obtained from the Minerals Management Service at the following addresses: U.S. Department of the Interior Minerals Management Service 381 Elden Street Herndon VA, 20170 http://www.mms.gov/offshore/AlternativeEnergy/CapeWind.htm CITATION Suggested Citation: MMS (Minerals Management Service). 2010. Documentation of Section 106 Finding of Adverse Effect for the Cape Wind Energy Project (Revised). Prepared by B. M. Carrier Jones, editor, Ecosystem Management & Associates, Inc. Lusby, Maryland. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction........................................................................................................................ -

Bookletchart™ Martha's Vineyard

BookletChart™ Martha’s Vineyard – Eastern Part NOAA Chart 13238 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the ebbs south-southwestward. Wasque Shoal extends southward of Wasque Point, the southeastern National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration extremity of Chappaquiddick Island. The shoal, which dries about 2 miles National Ocean Service south of Wasque Point, rises abruptly from deep Muskeget Channel. Office of Coast Survey Martha’s Vineyard and Chappaquiddick Island have a combined length of 18 miles; the two islands are separated by Edgartown Harbor, Katama www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov Bay, and the narrow slough connecting them. The northern extremity of 888-990-NOAA Martha’s Vineyard is about 3 miles southeastward of the western end of Cape Cod. Martha’s Vineyard is well settled, especially along its northern What are Nautical Charts? shore, and is popular as a summer resort. Along the northern shore the island presents a generally rugged appearance. The southern shore is Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show low and fringed with ponds, none of which has navigable outlets to the water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much sea. Approaching from the south, the principal landmarks are a more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and standpipe at Edgartown, an aerolight near the center of the island, a efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial church spire near Chilmark in the western part, a tall radar tower north ships that carry America’s commerce.