Cold War Games: Operational Gaming and Interactive Programming in Historical and Contemporary Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Is Tt,E a Glow-Globe in Here, Too, but It Is the Only Source of Light

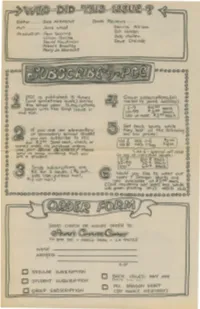

Edi+or" " , Bob Albrec.ht BooI<. Reviews"" Art, , , , , , Jane wood Denl"lis AlliSOn . C3i /I Holden Pr-oclv<:.ti on, ,r-b.m Scarvi e Li II io.n Quirke Bob ,v'Iullen Do.vld Ka.ufrYIG\Yl Dave De lisle Alber.,. Bradley' f'Ib.ry Jo Albrecht c 0000000 o ~ 0 o 0 • 0 o 0 o 0 Q~ PCC is publisnee\ 5 +imes • Grovp. svb5C.r,'phOn~(al/ 000 (ana sometimes more) dvrinq rl'lQilec +0 ~me add~ss): g -the 5c.hool tear. SubscriptionS 2-~ $4 00 eo.cJ, ! ~ be9in with 't-he fi~t 'Issve in 10-"" $ 3..so ea.c.h ~ o The .fall. /00 or-more $3°Oeach (; Q 0 tJ • Get bG\c.k issues while °8 o If you are an elementqt"Y 0 They IG\st ~+ the toIJowi""j Q or seconc:Ja.rY 9Chool stvcJ6,t low low pnc.es; e • you can00 subScribe to pee. vol I Nos 1-5 12 co 2 C!) for $3 , Send ~h,. check, or p 'U (/) rnoney order, No ~~G\se. orders, Vol Ir fVoI<:> I~!S qoo . e Use your $0,+)£ /ADDRESS' PlEQse eNO b - 5p!!cio.l arl',SSle (() o seno vs some eVidence tha1- you Or ml)( up InclividuQI Issues: () (I are G\ stu~",+, z.-~ 80 ~ ea.ch Cl) o 10-""'} '"70 t ectc. h 0 , Sit"lCJle. svb5c.ription\,. are. • /00 +' bO ea.cJ., . ! e $5 .far' 5 'ISSueS, (~ out- W lei \'k +0 '" o Side VSA-)urface MOIil,' ov .;t0v I e weG\r our Q A .. I cover, [)n,.qon shirts a.-e A ~ "'12 -air mai n(MJ G\vailable at $3$0 eod, '" 0 (Calif, res; dt'nts (Add While 0 sale~ ~')t, g with green prj "ti "va ' S.l'I D ""eo D LG LJ 0 ~OOo@c00000QctcD00(!) 00000000<0 0 0e~ooo OO(l)OOOO~OOO SEND cHECk' OR MONel ORDER 'R>: ~~~ Po 60)( 310 • MENLO PARI<. -

Game Development for Computer Science Education

Game Development for Computer Science Education Chris Johnson Monica McGill Durell Bouchard University of Wisconsin, Eau Bradley University Roanoke College Claire [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Michael K. Bradshaw Víctor A. Bucheli Laurence D. Merkle Centre College Universidad del Valle Air Force Institute of michael.bradshaw@ victor.bucheli@ Technology centre.edu correounivalle.edu.co laurence.merkle@afit.edu Michael James Scott Z Sweedyk J. Ángel Falmouth University Harvey Mudd College Velázquez-Iturbide [email protected] [email protected] Universidad Rey Juan Carlos [email protected] Zhiping Xiao Ming Zhang University of California at Peking University Berkeley [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT cation, including where and how they fit into CS education. Games can be a valuable tool for enriching computer science To guide our discussions and analysis, we began with the education, since they can facilitate a number of conditions following question: in what ways can games be a valuable that promote learning: student motivation, active learning, tool for enriching computer science education? adaptivity, collaboration, and simulation. Additionally, they In our work performed prior to our first face-to-face meet- provide the instructor the ability to collect learning metrics ing, we reviewed over 120 games designed to teach comput- with relative ease. As part of 21st Annual Conference on ing concepts (which is available for separate download [5]) Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education and reviewed several dozen papers related to game-based (ITiCSE 2016), the Game Development for Computer Sci- learning (GBL) for computing. Hainey [57] found that there ence Education working group convened to examine the cur- is \a dearth of empirical evidence in the fields of computer rent role games play in computer science (CS) education, in- science, software engineering and information systems to cluding where and how they fit into CS education. -

Hamurabi Wikipedia Article

Hamurabi - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 1/17/12 3:18 PM Hamurabi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Hamurabi is a text-based game of land and resource management and is one of the earliest computer games. Its name is a shortening of Hammurabi, reduced to fit an eight-character limit. Contents 1 History 2 Gameplay 3 Influence 4 References 5 External links History Doug Dyment wrote The Sumer Game in 1968 as a demonstration program for the FOCAL programming language, programming it on a DEC PDP-8. The game has often been inaccurately attributed to Richard Merrill, the designer of FOCAL. Once a version of BASIC was released for the PDP-8, David H. Ahl ported it to BASIC. The game spread beyond mainframes when Ahl published an expanded version of it in BASIC Computer Games, the first best-selling computer book.[1] The expanded version was renamed Hamurabi [sic] and added an end-of-game performance appraisal.[2] This version was then ported to many different microcomputers. Gameplay Like many BASIC games of the time, Hamurabi was mainly a game of numeric input. As the ruler, the player could buy and sell land, purchase grain and decide how much grain to release to his kingdom. Scott Rosenberg, in Dreaming in Code, wrote of his encounter with the game:[3] I was fifteen years old and in love with a game called Sumer, which put me in charge of an ancient city-state in the Fertile Crescent. Today's computer gamers might snicker at its crudity: its progress consisted of all-capital type pecked out line by line on a paper scroll. -

Learning to Code

PART ILEARNING TO CODE How Important is Programming? “To understand computers is to know about programming. The world is divided… into people who have written a program and people who have not.” Ted Nelson, Computer Lib/Dream Machines (1974) How important is it for you to learn to program a computer? Since the introduction of the first digital electronic computers in the 1940s, people have answered this question in surprisingly different ways. During the first wave of commercial computing—in the 1950s and 1960s, when 1large and expensive mainframe computers filled entire rooms—the standard advice was that only a limited number of specialists would be needed to program com- puters using simple input devices like switches, punched cards, and paper tape. Even during the so-called “golden age” of corporate computing in America—the mid- to late 1960s—it was still unclear how many programming technicians would be needed to support the rapid computerization of the nation’s business, military, and commercial operations. For a while, some experts thought that well-designed computer systems might eventually program themselves, requiring only a handful of attentive managers to keep an eye on the machines. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, the rapid emergence of personal computers (PCs), and continuing shortages of computer professionals, shifted popular thinking on the issue. When consumers began to adopt low-priced PCs like the Apple II (1977), the IBM PC (1981), and the Commodore 64 (1982) by the millions, it seemed obvious that ground-breaking changes were afoot. The “PC Revolution” opened up new frontiers, employed tens of thousands of people, and (according to some enthusiasts) demanded new approaches to computer literacy. -

Basic: the Language That Started a Revolution

TUTORIAL BASIC BASIC: THE LANGUAGE THAT TUTORIAL STARTED A REVOLUTION Explore the language that powered the rise of the microcomputer – JULIET KEMP including the BBC Micro, the Sinclair ZX80, the Commodore 64 et al. ike many of my generation, BASIC was the first John Kemeny, who spent time working on the WHY DO THIS? computer language I ever wrote. In my case, it Manhattan Project during WWII, and was inspired by • Learn the Python of was on a Sharp MZ-700 (integral tape drive, John von Neumann (as seen in Linux Voice 004), was its day L very snazzy) hooked up to my grandma’s old black chair of the Dartmouth Mathematics Department • Gain common ground with children of the 80s and white telly. For other people it was on a BBC from 1955 to 1967 (he was later president of the • Realise how easy we’ve Micro, or a Spectrum, or a Commodore. BASIC, college). One of his chief interests was in pioneering got it nowadays explicitly designed to make computers more computer use for ‘ordinary people’ – not just accessible to general users, has been around since mathematicians and physicists. He argued that all 1964, but it was the microcomputer boom of the late liberal arts students should have access to computing 1970s and early 1980s that made it so hugely popular. facilities, allowing them to understand at least a little And in various dialects and BASIC-influenced about how a computer operated and what it would do; languages (such as Visual Basic), it’s still around and not computer specialists, but generalists with active today. -

PROGRAMMING LEARNING GAMES Identification of Game Design Patterns in Programming Learning Games

nrik v He d a apa l sk Ma PROGRAMMING LEARNING GAMES Identification of game design patterns in programming learning games Master Degree Project in Informatics One year Level 22’5 ECTS Spring term 2019 Ander Areizaga Supervisor: Henrik Engström Examiner: Mikael Johannesson Abstract There is a high demand for program developers, but the dropouts from computer science courses are also high and course enrolments keep decreasing. In order to overcome that situation, several studies have found serious games as good tools for education in programming learning. As an outcome from such research, several game solutions for programming learning have appeared, each of them using a different approach. Some of these games are only used in the research field where others are published in commercial stores. The problem with commercial games is that they do not offer a clear map of the different programming concepts. This dissertation addresses this problem and analyses which fundamental programming concepts that are represented in commercial games for programming learning. The study also identifies game design patterns used to represent these concepts. The result of this study shows topics that are represented more commonly in commercial games and what game design patterns are used for that. This thesis identifies a set of game design patterns in the 20 commercial games that were analysed. A description as well as some examples of the games where it is found is included for each of these patterns. As a conclusion, this research shows that from the list of the determined fundamental programming topics only a few of them are greatly represented in commercial games where the others have nearly no representation. -

Unix Programmer's Manual

There is no warranty of merchantability nor any warranty of fitness for a particu!ar purpose nor any other warranty, either expressed or imp!ied, a’s to the accuracy of the enclosed m~=:crials or a~ Io ~helr ,~.ui~::~::.j!it’/ for ~ny p~rficu~ar pur~.~o~e. ~".-~--, ....-.re: " n~ I T~ ~hone Laaorator es 8ssumg$ no rO, p::::nS,-,,.:~:y ~or their use by the recipient. Furln=,, [: ’ La:::.c:,:e?o:,os ~:’urnes no ob~ja~tjon ~o furnish 6ny a~o,~,,..n~e at ~ny k:nd v,,hetsoever, or to furnish any additional jnformstjcn or documenta’tjon. UNIX PROGRAMMER’S MANUAL F~ifth ~ K. Thompson D. M. Ritchie June, 1974 Copyright:.©d972, 1973, 1974 Bell Telephone:Laboratories, Incorporated Copyright © 1972, 1973, 1974 Bell Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated This manual was set by a Graphic Systems photo- typesetter driven by the troff formatting program operating under the UNIX system. The text of the manual was prepared using the ed text editor. PREFACE to the Fifth Edition . The number of UNIX installations is now above 50, and many more are expected. None of these has exactly the same complement of hardware or software. Therefore, at any particular installa- tion, it is quite possible that this manual will give inappropriate information. The authors are grateful to L. L. Cherry, L. A. Dimino, R. C. Haight, S. C. Johnson, B. W. Ker- nighan, M. E. Lesk, and E. N. Pinson for their contributions to the system software, and to L. E. McMahon for software and for his contributions to this manual. -

Goose Game (2019) a Viewer

Digital Media, Society, and Culture Angus A. A. Mol AMS2019 • T.L. van der Linden Ah… The Memories • Iman and Caressa ask Is Fake News Conquering the World? • Zeynep On Podcasts • Liona on The Joker: A Story of Controversy • See also Alejandra on From Joker, With Love • Social Games • Bernardo on Gaming Friends in a Fight Against Solitude • Petra on Socializing in Online Games • Previously by Kevin (in DH2019): My Life Through Video Games DH2019 • Hiba on All is Fair in Love and Cookies • Philippe on a Da Vinci Robot • Sanem on What Color Are Bananas? • Connor has been Playing with Social Media • Kevin L. has been Playing in the Sandbox Video Games and other Digital Playgrounds Video games are ancient… Tennis for Two (Brookhaven, 1958) Nimrod (1951), world’s first The Sumerian Game(1964) videogame-playing computer Check it out (Hamurabi, BASIC version) Check it out Spacewar! (MIT, 1962) … Video Games are now! In the 20th Century, the moving image was the dominant cultural form. While music, architecture, the written word, and many other forms of expression flourished in the last century, the moving image came to dominate. Personal storytelling, news reporting, epic cultural narratives, political propaganda – all were expressed most powerfully through film and video. The rise of the moving image is tightly bound to the rise of information; film and video as media represent linear, non-interactive information that is accessed by Untitled Goose Game (2019) a viewer. The Ludic Century is an era of games. When information is put at play, game-like experiences replace linear media. -

Subterranean Space As Videogame Place | Electronic Book Review

electronic home about policies and submissions log in tags book share: facebook google+ pinterest twitter review writing under constraint first person technocapitalism writing (post)feminism electropoetics internet nation end construction critical ecologies webarts image + narrative music/sound/noise critical ecologies fictions present search Vibrant Wreckage: Salvation and New View full-screen This essay appears in these Materialism in Moby-Dick and Ambient gatherings: Parking Lot by Dale Enggass Cave Gave Game: Subterranean Space as 2018-05-29 Videogame Place Digital and Natural Ecologies by Dennis Jerz and David Thomas A Strange Metapaper on Computing 2015-10-06 Natural Language by Manuel Portela and Ana Marques daJerz and Thomas identify our fascination with Silva natural cave spaces, and then chart that 2018-05-07 fascination as it descends into digital realms, all in order to illustrate the importance of “the cave” as a metaphor for how we interact with our environment. Beyond Ecological Crisis: Niklas Luhmann’s Theory of Social Systems by Hannes Bergthaller 2018-04-01 Note: This essay is a part of a “gathering” on the topic of digital and natural ecologies. Thirteen Ways of Looking at ElectronicIn the popular conception of game development, fantastic videogame spaces Literature, or, A Print Essai on Tone in Electronic Literature, 1.0 are whimsically spun from the intangible thread of computer code. Like by Mario Aquilina and Ivan Callus literary authors, videogame developers take on the roles of dreamers of new 2018-02-04 places and inventors of new worlds. This popular notion remains at odds with the relatively small number of formal game spaces typically found in Thinking With the Planet: a Review of Tvideogames.he In his chapter “Space in the Video Game” Mark J.P. -

Fifty Years in Home Computing, the Digital Computer and Its Private Use(Er)S

International Journal of Parallel, Emergent and Distributed Systems ISSN: 1744-5760 (Print) 1744-5779 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gpaa20 Fifty years in home computing, the digital computer and its private use(er)s Stefan Höltgen To cite this article: Stefan Höltgen (2020) Fifty years in home computing, the digital computer and its private use(er)s, International Journal of Parallel, Emergent and Distributed Systems, 35:2, 170-184, DOI: 10.1080/17445760.2019.1597085 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17445760.2019.1597085 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 26 Mar 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 354 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gpaa20 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PARALLEL, EMERGENT AND DISTRIBUTED SYSTEMS 2020, VOL. 35, NO. 2, 170–184 https://doi.org/10.1080/17445760.2019.1597085 Fifty years in home computing, the digital computer and its private use(er)s Stefan Höltgen Department for Musicology and Media Science, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The following chapter will discuss the relation between home computer his- Received 13 March 2019 tory and computer programming – with a focus on game programming. Accepted 16 March 2019 The nurseries of the early 1980s are the origins of the later computer game KEYWORDS industry and the private use of microcomputers becomes an essential part Homecomputer; computer of the ‘playful’ exploration and emancipation of technology. -

Setting up a Portable Intellivision Development Environment on Your Android Phone

Portable Intellivision Development Environment for Phones December 27, 2019 Setting up a Portable Intellivision Development Environment on Your Android Phone Written by Michael Hayes [email protected] Date of Last Modification: December 27, 2019 (Note: don’t let the length of this document intimidate you. It’s designed to be easy-to- follow, not concise. Also, this is something you will only have to do once.) Introduction You have a portable Android phone and a physical keyboard connected to it. You now have some experience developing in IntyBASIC. You would like to do future development using only your phone and keyboard, so you can develop anywhere you’re at in the cracks of time in your busy schedule. You may not know a darn thing about Linux and can’t be bothered to “root” your phone. This document is for you. Disclaimer I feel it is imperative to put this on the first page: Neither I nor Midnight Blue International, LLC are responsible for anything bad that happens to you or your phone for the use of any of the information in this text. Neither I nor Midnight Blue International, LLC are responsible if you get fired from your job because you got caught writing games on company time. Neither I nor Midnight Blue International, LLC are responsible if your Life Partner walks out on you because you’re too busy making games anymore. Standard data rates apply with your mobile carrier, blah blah blah. You will need: • A phone with Android 7 or higher and about 550M internal storage space. -

Aesthetic Illusion in Digital Games

Aesthetic Illusion in Digital Games Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Karl‐Franzens‐Universität Graz vorgelegt von Andreas SCHUCH am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: O.Univ.‐Prof. Mag.art. Dr.phil. Werner Wolf Graz, 2016 0 Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2 2 The Transmedial Nature of Aesthetic Illusion ......................................................... 3 3 Types of Absorption in Digital Games .................................................................... 10 3.1 An Overview of Existing Research on Immersion and Related Terms in the Field of Game Studies ........................................................................................... 12 3.2 Type 1: Ludic Absorption ..................................................................................... 20 3.3 Type 2: Social Absorption .................................................................................... 24 3.4 Type 3: Perceptual Delusion ................................................................................ 26 3.5 Type 4: Aesthetic Illusion .................................................................................... 29 3.6 Comparing and Contrasting Existing Models of Absorption ........................... 30 4 Aesthetic Illusion in Digital Games ......................................................................... 34 4.1 Prerequisites and Characteristics of Aesthetic Illusion