What Was This Thing Called Jazz?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of Fall 8-21-2012 Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 Version of 08/21/2012 This essay is a work in progress. It was uploaded for the first time in August 2012, and the present document is the first version. The author welcomes comments, additions, and corrections ([email protected]). Black US Army bands and their bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts This essay sketches the story of the bands and bandmasters of the twenty seven new black army regiments which served in the U.S. Army in World War I. They underwent rapid mobilization and demobilization over 1917-1919, and were for the most part unconnected by personnel or traditions to the long-established bands of the four black regular U.S. Army regiments that preceded them and continued to serve after them. Pressed to find sufficient numbers of willing and able black band leaders, the army turned to schools and the entertainment industry for the necessary talent. -

2014-2015 Fine Arts Mid-Season Brochure

Deana Martin Photo credit: Pat Lambert The Fab Four NORTH CENTRAL COLLEGE Russian National SEASON Ballet Theatre 2015 WINTER/SPRING Natalie Cole Robert Irvine 630-637-SHOW (7469) | 3 | JA NUARY 2015 Event Price Page # January 8, 9, 10, 11 “October Mourning” $10, $8 4 North Central College January 16 An Evening with Jazz Trumpeter Art Davis $20, $15 4 January 18 Chicago Sinfonietta “Annual Tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” $58, $46 4 January 24 27th Annual Gospel Extravaganza $15, $10 4 Friends of the Arts January 24 Jim Peterik & World Stage $60, $50 4 January 25 Janis Siegel “Nightsongs” $35, $30 4 Thanks to our many contributors, world-renowned artists such as Yo-Yo Ma, the Chicago FEbrUARY 2015 Event Price Page # Symphony Orchestra, Vienna Boys Choir, Wynton Marsalis, Celtic Woman and many more have February 5, 6, 7 “True West” $5, $3 5 performed in our venues. But the cost of performance tickets only covers half our expenses to February 6, 7 DuPage Symphony Orchestra “Gallic Glory” $35 - $12 5 February 7 Natalie Cole $95, $85, $75 5 bring these great artists to the College’s stages. The generous support from the Friends of the February 13 An Evening with Jazz Vocalist Janice Borla $20, $15 5 Arts ensures the College can continue to bring world-class performers to our world-class venues. February 14 Blues at the Crossroads $65, $50 5 February 21 Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn $65, $50 6 northcentralcollege.edu/shows February 22 Robin Spielberg $35, $30 6 Join Friends of the Arts today and receive exclusive benefits. -

Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 3-2-2018 Black US Army Bands and Their aB ndmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the African American Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Music Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Black US Army Bands and Their aB ndmasters in World War I" (2018). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 67. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/67 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 Version of 04/02/2018 This is the third version, put on-line in 2018, of this work-in-progress. This essay was put on-line for the first time in 2012, at (https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpuB/25/), and a second version was put on-line in 2016, at (https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpuB/55/). The author is grateful to those who have contacted him aBout this work and welcomes further comments, additions, and corrections ([email protected]). Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts This essay sketches the story of the Bands and Bandmasters of the twenty seven new black army regiments which served in the U.S. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

A Time to Heal: Using Art As an Aid to Trauma Recovery

Handbook of Trauma and Loss !1 A Time to Heal: Using Art as an Aid to Trauma Recovery The ultimate goal of all art is relief from suffering and the rising above it. Gustav Mahler Since the beginning of time, the arts have always been indispensable voices for both protest and solace of trauma. In every era artists — be they poets, dancers, musi- cians, sculptors, painters, cartoonists, filmmakers —have crafted in various forms or me- dia, their responses to tragic events. At the time of this writing, terrorist attacks are ram- pant all over the world. In explicit detail, television, newspapers and social media report breaking news of disasters man-made and natural. Here in Boston, we endured the marathon bombing, following the trauma connected to the national 9/11 event. (Two of the hijacked flights that slammed into the World Trade Center towers originated in Bos- ton.) In responses to such events, and as a way to help people cope with what hap- pened, spontaneously conceived art forms were offered to the public. For example, out- side their offices in downtown Boston, architects placed wooden blocks, colored markers and other art supplies on the sidewalk inviting passersby to help design and construct the block sculpture memorial evolving in the building’s lobby (Figure 1). ! ! Figure 1 Figure 2A Handbook of Trauma and Loss !2 Figure 1. © CBT Architects, Inc., 110 Canal St., Boston, MA 02114. Used with permis- sion. Initially published in “Public Tragedy and the Arts,” in Living With Grief Coping with Public Tragedy, Lattanzi-Licht, M, Doka, K, (Eds), NY: Hospice Foundation of America/Brunner Routledge, 2003. -

For Alto Saxophone and Piano Wade Howles University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 2017 The nflueI nce of Jazz Elements in Don Freund's Sky Scrapings for Alto Saxophone and Piano Wade Howles University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Composition Commons, and the Ethnomusicology Commons Howles, Wade, "The nflueI nce of Jazz Elements in Don Freund's Sky Scrapings for Alto Saxophone and Piano" (2017). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 113. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/113 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE INFLUENCE OF JAZZ ELEMENTS IN DON FREUND’S SKY SCRAPINGS FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO by Jason Wade Howles A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Paul Haar Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2017 THE INFLUENCE OF JAZZ ELEMENTS IN DON FREUND’S SKY SCRAPINGS FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO J. Wade Howles, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2017 Adviser: Paul Haar Jazz influence surfaces within traditional repertoire for the saxophone more often than other instruments. This is due to the saxophone’s close association with the jazz idiom. -

The Influence of Louis Armstrong on the Harlem Renaissance 1923-1930

ABSTRACT HUMANITIES DECUIR, MICHAEL B.A. SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS, 1987 M.A. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, 1989 THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 Committee Chair: Timothy Askew, Ph.D. Dissertation dated August 2018 This research explores Louis Armstrong’s artistic choices and their impact directly and indirectly on the African-American literary, visual and performing arts between 1923 and 1930 during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance. This research uses analyses of musical transcriptions and examples of the period’s literary and visual arts to verify the significance of Armstrong’s influence(s). This research also analyzes the early nineteenth century West-African musical practices evident in Congo Square that were present in the traditional jazz and cultural behaviors that Armstrong heard and experienced growing up in New Orleans. Additionally, through a discourse analysis approach, this research examines the impact of Armstrong’s art on the philosophical debate regarding the purpose of the period’s art. Specifically, W.E.B. Du i Bois’s desire for the period’s art to be used as propaganda and Alain Locke’s admonitions that period African-American artists not produce works with the plight of blacks in America as the sole theme. ii THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY MICHAEL DECUIR DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 2018 © 2018 MICHAEL DECUIR All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest debt of gratitude goes to my first music teacher, my mother Laura. -

Paquito D' Rivera

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. PAQUITO D’RIVERA NEA Jazz Master (2005) Interviewee: Paquito D’ Rivera (June 4, 1948 - ) Interviewer: Willard Jenkins with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: June 11, 2010 and June 12, 2010 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 68 pp. Willard: Please give us your full given name. Paquito: I was born Francisco Jesus Rivera Feguerez, but years later I changed to Paquito D’Rivera. Willard: Where did Paquito come from? Paquito: Paquito is the little for Francisco in Latin America. Tito, or Paquito Paco, it is a little word for Francisco. My father’s name was Francisco also, but, his little one was Tito, like Tito Puente. Willard: And what is your date of birth? Paquito: I was born June 4, 1948, in Havana, Cuba. Willard: What neighborhood in Havana were you born in? Paquito: I was born and raised very close, 10 blocks from the Tropicana Cabaret. The wonderful Tropicana Night-Club. So, the neighborhood was called Marinao. It was in the outskirts of Havana, one of the largest neighborhoods in Havana. As I said before, very close to Tropicana. My father used to import and distribute instruments and accessories of music. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] Page | 1 Willard: And what were your parents’ names? Paquito: My father’s name was Paquito Francisco, and my mother was Maura Figuerez. Willard: Where are your parents from? Paquito: My mother is from the Riento Province, the city of Santiago de Cuba. -

Earshot Jazz Festival in November, P 4

A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community Nov 2005 Vol. 21, No. 11 EARSHOT JAZZSeattle, Washington Earshot Jazz Festival in November, P 4 Conversation with Randy Halberstadt, P 21 Ballard Jazz Festival Preview, P 23 Gary McFarland Revived on Film, P 25 PHOTO BY DANIEL SHEEHAN EARSHOT JAZZ A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community ROCKRGRL Music Conference Executive Director: John Gilbreath Earshot Jazz Editor: Todd Matthews Th e ROCKRGRL Music Conference Highlights of the 2005 conference Editor-at-Large: Peter Monaghan 2005, a weekend symposium of women include keynote addresses by Patti Smith Contributing Writers: Todd Matthews, working in all aspects of the music indus- and Johnette Napolitano; and a Shop Peter Monaghan, Lloyd Peterson try, will take place November 10-12 at Talk Q&A between Bonnie Raitt and Photography: Robin Laanenen, Daniel the Madison Renaissance Hotel in Seat- Ann Wilson. Th e conference will also Sheehan, Valerie Trucchia tle. Th ree thousand people from around showcase almost 250 female-led perfor- Layout: Karen Caropepe Distribution Coordinator: Jack Gold the world attended the fi rst ROCKRGRL mances in various venues throughout Mailing: Lola Pedrini Music Conference including the legend- downtown Seattle at night, and a variety Program Manager: Karen Caropepe ary Ronnie Spector and Courtney Love. of workshops and sessions. Registra- Icons Ann and Nancy Wilson of Heart tion and information at: www.rockrgrl. Calendar Information: mail to 3429 were honored with the fi rst Woman of com/conference, or email info@rockrgrl. Fremont Place #309, Seattle WA Valor lifetime achievement Award. com. 98103; fax to (206) 547-6286; or email [email protected] Board of Directors: Fred Gilbert EARSHOT JAZZ presents.. -

The Black Women's Contribution to the Harlem Renaissance 1919-1940

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University Abd El Hamid Ibn Badis Faculty of Foreign Languages English Language The Black Women's Contribution to the Harlem Renaissance 1919-1940 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master in Literature and Interdisciplinary Approaches Presented By: Rahma ZIAT Board of Examiners: Chairperson: Dr. Belghoul Hadjer Supervisor: Djaafri Yasmina Examiner: Dr. Ghaermaoui Amel Academic Year: 2019-2020 i Dedication At the outset, I have to thank “Allah” who guided and gave me the patience and capacity for having conducted this research. I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my family and my friends. A very special feeling of gratitude to my loving father, and mother whose words of encouragement and push for tenacity ring in my ears. To my grand-mother, for her eternal love. Also, my sisters and brother, Khadidja, Bouchra and Ahmed who inspired me to be strong despite many obstacles in life. To a special person, my Moroccan friend Sami, whom I will always appreciate his support and his constant inspiration. To my best friend Fethia who was always there for me with her overwhelming love. Acknowledgments Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mrs.Djaafri for her continuous support in my research, for her patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. Her guidance helped me in all the time of research and writing of this thesis. I could not have imagined having a better advisor and mentor for dissertation. I would like to deeply thank Mr. -

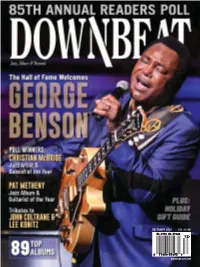

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Social Dance and Jazz, 1917–1935 Key People

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 3: “Catching as the Small-Pox”: Social Dance and Jazz, 1917‒1935 Key People Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899–1974): Composer and pianist widely regarded as one of the most important American musicians of the twentieth century. Eubie Blake (1883–1983): Ragtime pianist and composer who began his career with James Reese Europe’s orchestra in 1916 and, along with Noble Sissle, launched the first successful all-black Broadway musical, Shuffle Along. James “Bubber” Miley (1903–1932): Influential trumpeter who created his signature sound by combining two types of mutes and creating a deep growl in his throat. James Reese Europe (1880-1919): African American musical director hired by Vernon and Irene Castle; career as a popular dance musician skyrocketed, but continued to devote energy to establishing a black symphony orchestra that would specialize in the works of African American composers. Justo Don Azpiazú (1893–1943): Leader of the Havana Casino Orchestra who gave American audiences their first taste of authentic Cuban music. King Joe Oliver (1885–1938): Cornetist and mentor to Louis Armstrong who lead King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band and made some of the first recording by black musicians from New Orleans. Louis Armstrong (1901–1971): Brilliant cornetist and singer affectionately known as “Satchelmouth” or “Satchmo” who built a six-decade musical career that challenged the distinction that is sometimes drawn between the artistic and commercial sides of jazz music. Nick LaRocca (1889‒1961): Leader of a white group from New Orleans called the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, recordings of “Libery Stable Blues” and “Dixieland Jass Band One-Step” were released in 1917.