Issue 24, November 2014 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Veritable Revolution: the Court of Criminal Appeal in English

A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS B.A. University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1986 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 © 2012 CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 Cecile Arden Phillips, Candidate for the Masters of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT In a historic speech to the House of Commons on April 17, 1907, British Attorney General, John Lawson Walton, proposed the formation of what was to be the first court of criminal appeal in English history. Such a court had been debated, but ultimately rejected, by successive governments for over half a century. In each debate, members of the judiciary declared that a court for appeals in criminal cases held the potential of destroying the world-respected English judicial system. The 1907 debates were no less contentious, but the newly elected Liberal government saw social reform, including judicial reform, as their highest priority. After much compromise and some of the most overwrought speeches in the history of Parliament, the Court of Criminal Appeal was created in August 1907 and began hearing cases in May 1908. A Veritable Revolution is a social history of the Court’s first fifty years. There is no doubt, that John Walton and the other founders of the Court of Criminal Appeal intended it to provide protection from the miscarriage of justice for English citizens convicted of criminal offenses. -

Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Honors Theses Student Scholarship Fall 2015 Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom Rachel Gaines Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Gaines, Rachel, "Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom" (2015). Honors Theses. 293. https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses/293 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i EASTERN KENTUCKY UNIVERSITY Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom Honors Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements of HON 420 Fall 2015 By Rachel Gaines Faculty Mentor Dr. Sucheta Mohanty Department of Government ii Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom Rachel Gaines Faculty Mentor Dr. Sucheta Mohanty, Department of Government Abstract: Capital punishment (sometimes referred to as the death penalty) is the carrying out of a legal sentence of death as punishment for crime. The United States Supreme Court has most recently ruled that capital punishment is not unconstitutional. -

Ruth Ellis in the Condemned Cell : Voyeurism and Resistance.', Prison Service Journal., 199

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 30 August 2012 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Unknown Citation for published item: Seal, L. (2012) 'Ruth Ellis in the condemned cell : voyeurism and resistance.', Prison Service journal., 199 . pp. 17-19. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/psj.html Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Ruth Ellis in the Condemned Cell: Voyeurism and Resistance Dr Lizzie Seal is a Lecturer in Criminology at Durham University. Introduction Holloway’s condemned cell. This provided the next phase of the story, in which a young, attractive mother faced When Ruth Ellis became the last woman to be execution for a murder that seemed eminently executed in England and Wales in July 1955, understandable. Particularly compelling was her execution had long been something which took insistence that she did not want to be reprieved and was place in private. -

The Foreign Service Journal, July-August 2011

AFSA DISSENT AWARDS INSIDE! $4.50 / JULY-AUGUST 2011 OREIGN ERVICE FJ O U R N A L S THE MAGAZINE FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS PROFESSIONALS SPEAKING TRUTH TO POWER Constructive Dissent in the Foreign Service — advertisement — OREIGN ERVICE FJ O U R N A L S CONTENTS July-August 2011 Volume 88, No.7-8 F OCUSON D i s s e n t WHAT IF I DISAGREE? / 18 Our nation has benefited greatly from the institutionalization of dissent in the culture of the Foreign Service. By Thomas D. Boyatt DISSENT IN THE KISSINGER ERA / 21 State’s Dissent Channel is a unique government institution. Here is a look at its origins and early history. By Hannah Gurman SAVIOR DIPLOMATS: FINALLY RECEIVING THEIR DUE / 30 Seven decades later, the examples of these 60 courageous public servants Cover illustration by Marian Smith. still offer lessons for members of today’s Foreign Service. This oil painting, “To Remember,” By Michael M. Uyehara was among her entries to AFSA’s 2011 Art Merit Award competition. F EATURES A CONSUMMATE NEGOTIATOR: ROZANNE L. RIDGWAY / 56 RESIDENT S IEWS P ’ V / 5 Last month AFSA recognized Ambassador Ridgway’s many contributions Moving Forward Together to American diplomacy and her lifetime of public service. By Susan R. Johnson By Steven Alan Honley SPEAKING OUT / 15 TAKING DIPLOMATIC PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION SERIOUSLY / 66 Needed: A Professional A new American Academy of Diplomacy study makes a compelling case Specialization in International for establishing a systematic training regimen at State. Organization Affairs By Robert M. Beecroft By Edward Marks THE KINGS AND I / 70 EFLECTIONS R / 76 An FSO explains why consorting with heads of state The Greater Honor isn’t everything it’s cracked up to be. -

Correcting Injustice: Studying How the United Kingdom and the United States Review Claims of Innocence

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2009 Correcting Injustice: Studying How the United Kingdom and the United States Review Claims of Innocence Lissa Griffin Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Lissa Griffin, Correcting Injustice: Studying How the United Kingdom and the United States Review Claims of Innocence, 41 U. Tol. L. Rev. 107 (2009), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/653/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORRECTING INJUSTICE: STUDYING HOW THE UNITED KINGDOM AND THE UNITED STATES REVIEW CLAIMS OF INNOCENCE Lissa Griffin* ' "England and America are two countries [separated] by a common language." JN the United States, the problem of wrongful convictions continues to Lelude a solution.2 Many approaches to the problem have been suggested, and some have been tried. Legislators,3 professional organizations,4 and 5 scholars have suggested various systemic changes to improve the accuracy of6 the adjudication process and to correct wrongful convictions after they occur. Despite these efforts, the demanding standard of review used by U.S. courts, combined with strict retroactivity rules, a refusal to consider newly discovered * Professor of Law, Pace University School of Law. The author wishes to thank John Wagstaff, Legal Adviser to the Criminal Cases Review Commission; Laurie Elks, Esq. -

The Abolition of the Death Penalty in the United Kingdom

The Abolition of the Death Penalty in the United Kingdom How it Happened and Why it Still Matters Julian B. Knowles QC Acknowledgements This monograph was made possible by grants awarded to The Death Penalty Project from the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, the United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the Sigrid Rausing Trust, the Oak Foundation, the Open Society Foundation, Simons Muirhead & Burton and the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture. Dedication The author would like to dedicate this monograph to Scott W. Braden, in respectful recognition of his life’s work on behalf of the condemned in the United States. © 2015 Julian B. Knowles QC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Copies of this monograph may be obtained from: The Death Penalty Project 8/9 Frith Street Soho London W1D 3JB or via our website: www.deathpenaltyproject.org ISBN: 978-0-9576785-6-9 Cover image: Anti-death penalty demonstrators in the UK in 1959. MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY 2 Contents Foreword .....................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................5 A brief -

Convicting the Innocent: a Triple Failure of the Justice System

Convicting the Innocent: A Triple Failure of the Justice System BRUCE MACFARLANE* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. DEFINING THE ISSUE 405 II. INTERNATIONAL REVIEWS DURING THE PAST CENTURY 406 A. American Prison Congress Review (1912) 406 B. U.S. State Department Document (1912) 407 C. Borchard Study (1932) 408 D. Franks’ Study (1957) 409 E. Du Cann Study (1960) 411 F. Radin Study (1964) 412 G. Brandon and Davies Study (1973) 413 H. Royal Commissions in Australia and New Zealand During the 1980s 413 I. IRA Bombings in Britain (1980s) 417 1. Guildford Four 417 2. Birmingham Six 418 3. Maguire Seven 419 4. Judith Ward 419 * Bruce A. MacFarlane, Q.C., of the Manitoba and Alberta Bars, Professional Affiliate, Faculty of Law, University of Manitoba, formerly Deputy Attorney General of Manitoba (1993-2005). This essay is based on an earlier paper presented at the Heads of Prosecution Agencies in the Commonwealth Con- ference at Darwin, Australia on 7 May 2003, the Heads of Legal Aid Plans in Canada on 25 August 2003 and, once again, at the Heads of Prosecution Agencies in the Commonwealth Conference at Bel- fast, Northern Ireland and Dublin, Ireland during the week of 4 September 2005. Following these pres- entations, counsel from England, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Hong Kong and the United States, as well as Canadian provinces, provided me with a number of helpful comments. I have benefited greatly from this advice. I also wish to express my appreciation to Julia Gurr, for her assistance in updating the paper during the summer of 2005. -

The “Near Miss” of Liam Allan: Critical Problems in Police Disclosure, Investigation Culture, and the Resourcing of Criminal Justice

The “near miss” of Liam Allan: Critical Problems in Police Disclosure, Investigation Culture, and the Resourcing of Criminal Justice Dr Tom Smith Lecturer in Law, University of the West of England, Bristol Miscarriages of justice have historically acted as catalysts for reform. It seems we only learn to fix the most serious problems – often obvious to those at the coal-face of practice – once the damage is done. Miscarriages include a failure to deliver justice for those victimised by crime, but as egregious is the conviction of the innocent, and the consequent punishment and social stigma attached to them.1 There are many examples, old and new. The secretive exploits of the Court of Star Chamber led to the abolition of investigative torture in the 1640s.2 Later in the same century, the ‘Popish Plot’ treason trials led to the lifting of the ban on defence lawyers.3 The cases of George Edalji and Adolf Beck led to the creation of the Court of Criminal Appeal in 1908.4 In the 1950s and 1960s, several high-profile executions (including Timothy Evans, James Hanratty, Ruth Ellis, and Derek Bentley) generated significant debate about and public opposition to the death penalty – which was abolished for murder in 1965 (and later for the two remaining eligible offences (piracy and treason) by the Human Rights Act 1998 and Crime and Disorder Act 1998).5 In the 1970s, the Maxwell Confait affair and the consequent Fisher Inquiry instigated the creation of the Philips Commission, and eventually the passage of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) -

Faction: How to Combine Fact and Fiction to Make Drama David Porter

Faction: how to combine fact and fiction to make drama GCSE David Porter GCSE Introduction David Porter is former Head of Performing Arts at Kirkley High School, In a part-factual, perhaps historical story, facts are supplemented with a certain Lowestoft, teacher and one-time amount of fiction. Who said what, what occurred behind the facts? The mixture is children’s theatre performer. Freelance called ‘faction’ and is necessary to make drama work. The case of Ruth Ellis, the writer, blogger, editor he is a senior last woman in England to be hanged, offers a retelling of events to shed light on assessor for A level Performance Studies, IGSCE Drama moderator and GCSE the people and their actions and explore dramatic possibilities. Drama examiner. Learning objectives By the end of this scheme, learners will have: f Explored turning historical situations into performance f Considered how the addition of fiction makes fact workable on stage f Developed collaborative and solo characterisation skills. Scheme in summary After an introduction to faction, the case of Ruth Ellis is explored with a view to considering both some of the issues raised and to developing a piece of credible, character-driven performance, suitable for GCSE devising work. Going beyond documentary or docu-drama, faction offers insight into people. Lesson 1: Developing faction Introduction to taking given facts and adding fiction to make them into performance drama. Drama vocabulary used: Cross-cutting, narrator(s) in role, Lesson 2: Ruth Ellis (1) characterisation, hot seating, mime, Using known facts about Ruth Ellis to build four scenes from her life. -

Chained to the Prison Gates

Chained to the prison gates A comparative analysis of two modern penal reform campaigners Cover image shows Pauline Campbell protesting at Styal prison, 18 May 2006. Chained to the prison gates: A comparative analysis of two modern penal reform campaigners A report for the Howard League for Penal Reform by Laura Topham Chained to the prison gates Chained to the prison gates: A comparative analysis of two modern penal reform campaigners Contents Introduction 5 1 Background 8 2 Pauline Campbell 11 3 Violet Van der Elst 18 4 How effective were Violet Van der Elst and Pauline Campbell? 24 Conclusion 35 References 37 Appendix 1: List of executions targeted by Violet Van der Elst’s campaign mentioned in this report 40 Appendix 2: List of women who have committed suicide in prison since 2004 42 Chained to the prison gates Introduction Pauline Campbell Violet Van der Elst ‘Where there is injustice there will be protest’. This was the powerful slogan coined by the late penal reformer Pauline Campbell. It not only captures the driving force behind her campaigning, but is also an idea which resonates with anyone who believes in democracy and fairness – particularly in the current climate of resurging direct action and public protest. Seventy years earlier the same ideal led Violet Van der Elst to conduct a similar campaign of direct action against capital punishment. Both women, divided by decades, demonstrated ceaselessly outside prisons, though this led to criminal proceedings, illness, misery and financial ruin. They remained unalterably committed to their respective causes – for Van der Elst, the abolition of the death penalty; for Campbell, better care of female prisoners. -

Daily Express

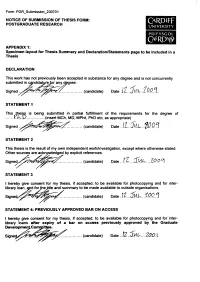

Form: PGR_Submission_200701 NOTICE OF SUBMISSION OF THESIS FORM: POSTGRADUATE RESEARCH Ca r d if f UNIVERSITY PRIFYSGOL CAERDVg) APPENDIX 1: Specimen layout for Thesis Summary and Declaration/Statements page to be included in a Thesis DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in capdidatyrefor any degree. S i g n e d ................. (candidate) Date . i.L.. 'IP .Q . STATEMENT 1 This Thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Y .l \.D ..................(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed (candidate) Date .. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Sig (candidate) Date STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, apd for thefitle and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signe4x^^~^^^^pS^^ ....................(candidate) Date . STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Graduate Developme^Committee. (candidate) Date 3ml-....7.00.1 EXPRESSIONS OF BLAME: NARRATIVES OF BATTERED WOMEN WHO KILL IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY DAILY EXPRESS i UMI Number: U584367 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

2000 Membership Cards ($1) Reserved Over the Phone

See you at the mo vi e s . Proud supporter of qu ee r events everywher e. Van c o u v er’s Gay & Lesbian Biweekly 1033 Davie Street, Suite 501, V an c o u v er, BC V6E 1M7 Tel : 604.684.9696 Fax : 604.684.9697 Email : xw ad ve r t i s i n g @ x t r a . c a CONTENTS Z Orientation 3 Sponsors 4 Acknowledgements 5 More Sponsors 6 Politicians’ Welcomes 8 Out On Screen Welcome 11 Mission Statement / Who We Are 13 Gerry Brunet Memorial Award 15 Presenting Community Programming 17 Opening Gala Z Punks 19 Opening Gala Z Chutney Popcorn 21 Z But I’m a Cheerleader 22 Z Wolves of Kromer / Hell for Leather 22 Z Gypsy Boys 23 Out On Screen Video Scholarship Program Z First Exposure 24 Z Millennial Guide to Gay Dating: Find ‘em, Love ‘em, Leave ‘em 25 Z Secrets Between Us 25 Z Intimates 26 Z Miguel / Michelle 26 Z Straightman / Campfire 27 CALENDAR 29 Z Living With Pride: Ruth Ellis @ 100 / Meeting Mr. Crisp 31 Z Love is an Art 31 Z Trans Shorts / Trans Panel 32 Z Our House / Baby Steps/ We’re Fathers Too 33 Z Two Brothers 33 Z Through Our Eyes: Women’s Shorts 34 Z Sexual Tourists: Going Bi Way 34 Z Working for Love 35 Essay 36 Z Latin Queens / Out and About / Stand by Your Man 37 Z Casablanket / Lovely is Your Name / Switch 39 Z Wicked: A Queer Exploration of Religion and Ritual 39 Z Queeressentials 40 Z And the Beat Goes On.