Prostate Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Finding Prostate Cancer Early

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is There Anything New in Prostate Cancer Screening?

IS THERE ANYTHING NEW IN PROSTATE CANCER SCREENING? ANDREW M.D. WOLF, MD, FACP ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF MEDICINE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA SCHOOL OF MEDICINE No financial disclosures Case Presentation 62 yo white man without significant past medical history presents for annual preventive visit. He has no family history of prostate cancer. He has mild urinary hesitancy and his prostate is mildly enlarged without induration or nodules. His PSA has been gradually rising: - 2011: 2.35 - 2013: 2.17 - 2017: 3.75 - 2019: 4.51 Where do we go from here? What’s New in Prostate Cancer Screening? Key Questions • Do we have any new evidence for or against screening? • Do we have anything better than the PSA? • What about the good old digital rectal exam? • Are we doing any better identifying who needs to be treated? • What do the experts recommend? Prostate Cancer Incidence & Mortality Over the Decades Source: Seer 9 areas & US Mortality Files (National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, Feb 2018 CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7-34. Do we have any new evidence for or against prostate cancer screening? Is Prostate Screening Still Controversial? ERSPC Results • Prostate cancer death rate 27% lower in screened group (p = 0.0001) at 13 yrs • Number needed to screen to save 1 life: 781 • NNS to prevent 1 case of metastatic cancer: ~350 • Number needed to diagnose to save 1 life: 27 • Major issue of over-diagnosis & over-treatment Schroder FH, et al. Lancet 2014;384: 2027–2035 • Controlled for differences in study design • Adjusted for lead-time • Both studies led to a ~ 25-32% reduction in prostate cancer mortality with screening compared with no screening Ann Intern Med 2017;167:449-455 • 415,000 British men 50-69 randomized to a single offer to screen vs usual care (info sheet on request) • One-time screen & then followed for 10 yrs • Men dx’d with prostate cancer randomized to treatment vs active surveillance JAMA 2018;319(9):883-895. -

Prostate Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention Risk Factors

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Prostate Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention Risk Factors A risk factor is anything that increases your chances of getting a disease such as cancer. Learn more about the risk factors for prostate cancer. ● Prostate Cancer Risk Factors ● What Causes Prostate Cancer? Prevention There is no sure way to prevent prostate cancer. But there are things you can do that might lower your risk. Learn more. ● Can Prostate Cancer Be Prevented? Prostate Cancer Risk Factors A risk factor is anything that raises your risk of getting a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed. But having a risk factor, or even several, does not mean that you will get the disease. 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Many people with one or more risk factors never get cancer, while others who get cancer may have had few or no known risk factors. Researchers have found several factors that might affect a man’s risk of getting prostate cancer. Age Prostate cancer is rare in men younger than 40, but the chance of having prostate cancer rises rapidly after age 50. About 6 in 10 cases of prostate cancer are found in men older than 65. Race/ethnicity Prostate cancer develops more often in African-American men and in Caribbean men of African ancestry than in men of other races. And when it does develop in these men, they tend to be younger. -

Profiling Prostate Cancer Therapeutic Resistance

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Profiling Prostate Cancer Therapeutic Resistance Cameron A. Wade 1 and Natasha Kyprianou 1,2,3,* 1 Departments of Urology, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, Kentucky, KY 40536, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, Kentucky, KY 40536, USA 3 Department of Toxicology & Cancer Biology, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, Kentucky, KY 40536, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-859-323-9812; Fax: +1-859-323-1944 Received: 1 March 2018; Accepted: 16 March 2018; Published: 19 March 2018 Abstract: The major challenge in the treatment of patients with advanced lethal prostate cancer is therapeutic resistance to androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) and chemotherapy. Overriding this resistance requires understanding of the driving mechanisms of the tumor microenvironment, not just the androgen receptor (AR)-signaling cascade, that facilitate therapeutic resistance in order to identify new drug targets. The tumor microenvironment enables key signaling pathways promoting cancer cell survival and invasion via resistance to anoikis. In particular, the process of epithelial-mesenchymal-transition (EMT), directed by transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), confers stem cell properties and acquisition of a migratory and invasive phenotype via resistance to anoikis. Our lead agent DZ-50 may have a potentially high efficacy in advanced metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) by eliciting an anoikis-driven therapeutic response. The plasticity of differentiated prostate tumor gland epithelium allows cells to de-differentiate into mesenchymal cells via EMT and re-differentiate via reversal to mesenchymal epithelial transition (MET) during tumor progression. -

CASODEX (Bicalutamide)

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION • Gynecomastia and breast pain have been reported during treatment with These highlights do not include all the information needed to use CASODEX 150 mg when used as a single agent. (5.3) CASODEX® safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for • CASODEX is used in combination with an LHRH agonist. LHRH CASODEX. agonists have been shown to cause a reduction in glucose tolerance in CASODEX® (bicalutamide) tablet, for oral use males. Consideration should be given to monitoring blood glucose in Initial U.S. Approval: 1995 patients receiving CASODEX in combination with LHRH agonists. (5.4) -------------------------- RECENT MAJOR CHANGES -------------------------- • Monitoring Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) is recommended. Evaluate Warnings and Precautions (5.2) 10/2017 for clinical progression if PSA increases. (5.5) --------------------------- INDICATIONS AND USAGE -------------------------- ------------------------------ ADVERSE REACTIONS ----------------------------- • CASODEX 50 mg is an androgen receptor inhibitor indicated for use in Adverse reactions that occurred in more than 10% of patients receiving combination therapy with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone CASODEX plus an LHRH-A were: hot flashes, pain (including general, back, (LHRH) analog for the treatment of Stage D2 metastatic carcinoma of pelvic and abdominal), asthenia, constipation, infection, nausea, peripheral the prostate. (1) edema, dyspnea, diarrhea, hematuria, nocturia, and anemia. (6.1) • CASODEX 150 mg daily is not approved for use alone or with other treatments. (1) To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP at 1-800-236-9933 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or ---------------------- DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ---------------------- www.fda.gov/medwatch The recommended dose for CASODEX therapy in combination with an LHRH analog is one 50 mg tablet once daily (morning or evening). -

Neuroendocrine Differentiation of Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

J Lab Med 2019; 43(2): 123–126 Laboratory Case Report Cátia Iracema Morais*, João Lobo, João P. Barreto, Cláudia Lobo and Nuno D. Gonçalves Neuroendocrine differentiation of prostatic adenocarcinoma – an important cause for castration-resistant disease recurrence https://doi.org/10.1515/labmed-2018-0190 awareness of this entity is crucial due to its underdiagno- Received December 3, 2018; accepted December 12, 2018; previously sis and adverse prognosis. published online February 15, 2019 Keywords: carcinoma; castration-resistant (D064129); cell Abstract transformation; neoplastic (D002471); neuroendocrine (D018278); prostate (D011467); prostatic neoplasms. Background: Neuroendocrine differentiation of prostatic carcinoma is a rare entity associated with metastatic castration-resistant disease. Among useful biomarkers of neuroendocrine differentiation, chromogranin A, sero- Introduction tonin, synaptophysin and neuron-specific enolase stand out, while total prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels are Neuroendocrine prostatic carcinoma is a rare and often low or undetectable. underdiagnosed histologic subtype. Despite the low Case presentation: We report a case of prostatic adenocar- incidence rate of primary neuroendocrine prostatic cinoma recurrence after a 6-year disease-free follow-up, in carcinoma (which represents under 1% of all prostate which increased serum chromogranin A levels and unde- cancers at diagnosis), 30–40% of patients who develop tectable total PSA provided a prompt indication of neu- metastasized castration-resistant -

U.S. Cancer Statistics: Male Urologic Cancers During 2013–2017, One of Three Cancers Diagnosed in Men Was a Urologic Cancer

Please visit the accessible version of this content at https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/data-briefs/no21-male-urologic-cancers.htm December 2020| No. 21 U.S. Cancer Statistics: Male Urologic Cancers During 2013–2017, one of three cancers diagnosed in men was a urologic cancer. Of 302,304 urologic cancers diagnosed each year, 67% were found in the prostate, 19% in the urinary bladder, 13% in the kidney or renal pelvis, and 3% in the testis. Incidence Male urologic cancer is any cancer that starts in men’s reproductive or urinary tract organs. The four most common sites where cancer is found are the prostate, urinary bladder, kidney or renal pelvis, and testis. Other sites include the penis, ureter, and urethra. Figure 1. Age-Adjusted Incidence Rates for 4 Common Urologic Cancers Among Males, by Racial/Ethnic Group, United States, 2013–2017 5.0 Racial/Ethnic Group Prostate cancer is the most common 2.1 Hispanic Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander urologic cancer among men in all 6.3 Testis Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native racial/ethnic groups. 1.5 Non-Hispanic Black 7.0 Non-Hispanic White 5.7 All Males Among non-Hispanic White and Asian/Pacific Islander men, bladder 21.8 11.4 cancer is the second most common and 29.4 kidney cancer is the third most Kidney and Renal Pelvis 26.1 common, but this order is switched 23.1 22.8 among other racial/ethnic groups. 18.6 • The incidence rate for prostate 14.9 cancer is highest among non- 21.1 Urinary Bladder 19.7 Hispanic Black men. -

Review Committee News—Urology

Review Committee News—Urology • Definitions of Board Pass Rates This is a reminder that programs will be cited for poor performance on the American Board of Urology examination if they average more than two standard deviations above the mean in failure rates over a five-year period. The RRC will only look at first-time test takers on Part One of the Board’s Qualifying Examination. The application of this standard began with programs reviewed after July 1, 2010. • Logging Ultrasound Procedures To define the current resident experience in performing urologic ultrasound procedures and to track this experience over time, the Urology Review Committee would like residents to log these cases starting July 1, 2012. Ultrasound cases include commonly performed procedures such as transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) with prostate biopsy, and non-TRUS biopsy procedures such as renal, pelvic, scrotal and penile ultrasound cases. The Review Committee is particularly interested in tracking resident involvement in non-TRUS biopsy ultrasound procedures. While TRUS-prostate biopsy will remain an index case with a minimum number required (25), there will be no minimum number of cases required for non- prostate ultrasound procedures. We ask that residents use one of the following CPT codes when logging these procedures: Category CPT code Scrotal 76870 Renal Retroperitoneal, limited (kidney only) 76775 Retroperitoneal, complete (both kidney and bladder) 76770 Transplant kidney ultrasound 76776 US guidance, intraoperative (e.g. during partial nephrectomy) 76998 US -

Clinical Summary: Screening for Prostate Cancer

Clinical Summary: Screening for Prostate Cancer Population Men aged 55 to 69 y Men 70 y and older The decision to be screened for prostate cancer should be Recommendation Do not screen for prostate cancer. an individual one. Grade: D Grade: C Before deciding whether to be screened, men aged 55 to 69 years should have an opportunity to discuss the potential benefits and harms of screening with their clinician and to incorporate their values and preferences in the decision. Screening offers a small potential benefit of reducing the chance of death from prostate cancer in some men. However, many men will experience potential harms of screening, including false-positive results that require additional testing and possible prostate biopsy; overdiagnosis and Informed Decision overtreatment; and treatment complications, such as incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Harms are greater for men 70 years Making and older. In determining whether this service is appropriate in individual cases, patients and clinicians should consider the balance of benefits and harms on the basis of family history, race/ethnicity, comorbid medical conditions, patient values about the benefits and harms of screening and treatment-specific outcomes, and other health needs. Clinicians should not screen men who do not express a preference for screening and should not routinely screen men 70 years and older. Risk Assessment Older age, African American race, and family history of prostate cancer are the most important risk factors for prostate cancer. Screening for prostate cancer begins with a test that measures the amount of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) protein in the blood. An elevated PSA level may be caused by prostate cancer but can also be caused by other conditions, including an enlarged Screening Tests prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia) and inflammation of the prostate (prostatitis). -

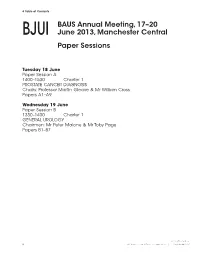

Paper Sessions

8 Table of Contents BAUS Annual Meeting, 17–20 BJUI June 2013, Manchester Central Paper Sessions Tuesday 18 June Paper Session A 1400–1530 Charter 1 PROSTATE CANCER DIAGNOSIS Chairs: Professor Martin Gleave & Mr William Cross Papers A1–A9 Wednesday 19 June Paper Session B 1330–1430 Charter 1 GENERAL UROLOGY Chairmen: Mr Peter Malone & Mr Toby Page Papers B1–B7 © 2013 The Authors 8 BJU International © 2013 BJU International | 111, Supplement 3, 8 Papers Abstracts 9 Tuesday 18 June BJUI Paper Session A 1400–1530 Charter 1 PROSTATE CANCER DIAGNOSIS Chairs: Professor Martin Gleave & Mr William Cross Papers A1–A9 A1 We then compared cancer yield in 50 Conclusion : Visualisation of each biopsy 3 D Visualisation of biopsy consecutive cases of positive prostate trajectory signifi cantly increases cancer trajectory and its clinical impact biopsies in the 2D vs. the 3D group (Part 2 detection rates and allows for a more in routine diagnostic TRUS guided of the study) through sampling of the prostate. Not only prostate biopsy Results : Th e results are tabulated as does this have a role in targeted biopsies K Narahari, A Peltier, R Van Velthoven follows but also in routine diagnostic biopsies. University Hospital of Wales, United Kingdom Introduction and Aims : Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided biopsy remains Part 1 the gold standard in prostate cancer Parameter 2D USS * 3D USS *** P value diagnosis however prostate remains n = 110 n = 110 Student ’s t test perhaps the only solid organ where biopsy Age in years 64 (46–90) 65 (46–84) NS is “blind”. Traditionally the surgeon would Mean (Range) prepare a “mental image” of the prostate PSA ng/ml 9 (0.5–70) 10 (0.5–59) NS and target his biopsy cores evenly to map Mean (Range) out the prostate as best as possible. -

Prostate Biopsy in the Staging of Prostate Cancer

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (1997) 1, 54±58 ß 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 1365±7852/97 $12.00 Review Prostate Biopsy in the staging of prostate cancer L Salomon, M Colombel, J-J Patard, D Gasman, D Chopin & C-C Abbou Service d'Urologie, CHU, Henri Mondor, CreÂteil, France The use of prostate biopsies was developed in parallel with progress in our knowledge of prostate cancer and the use of prostate-speci®c antigen (PSA). Prostate biopsies were initially indicated for the diagnosis of cancer, by the perineal approach under general anesthesia. Nowadays prostate biopsies are not only for diagnostic purposes but also to determine the prognosis, particularly before radical prostatectomy. They are performed in patients with elevated PSA levels, by the endorectal approach, sometimes under local anesthesia.(1±3) The gold standard is the sextant biopsy technique described by Hodge4,5, which is best to diagnose prostate cancer, particularly in case of T1c disease (patients with serum PSA elevation).6±13 Patients with a strong suspicion of prostate cancer from a negative series of biopsies can undergo a second series14;15 with transition zone biopsy16,17 or lateral biopsy.18,19 Karakiewicz et al 20 and Uzzo et al 21 proposed that the number of prostate biopsies should depend on prostate volume to improve the positivity rate. After the diagnosis of prostate cancer, initial therapy will depend on several prognostic factors. In the case of radical prostatectomy, the results of sextant biopsy provide a wealth of information.22,23 The aim of this report is to present the information given by prostate biopsy in the staging of prostate cancer. -

PROSTATE and TESTIS PATHOLOGY “A Coin Has Two Sides”, the Duality of Male Pathology

7/12/2017 PROSTATE AND TESTIS PATHOLOGY “A Coin Has Two Sides”, The Duality Of Male Pathology • Jaime Furman, M.D. • Pathology Reference Laboratory San Antonio. • Clinical Assistant Professor Departments of Pathology and Urology, UT Health San Antonio. Source: http://themoderngoddess.com/blog/spring‐equinox‐balance‐in‐motion/ I am Colombian and speak English with a Spanish accent! o Shannon Alporta o Lindsey Sinn o Joe Nosito o Megan Bindseil o Kandace Michael o Savannah McDonald Source: http://www.taringa.net/posts/humor/7967911/Sindrome‐de‐la‐ Tiza.html 1 7/12/2017 The Prostate Axial view Base Apex Middle Apex Sagittal view Reference: Vikas Kundra, M.D., Ph.D. , Surena F. Matin, M.D. , Deborah A. Kuban, M.Dhttps://clinicalgate.com/prostate‐cancer‐4/ Ultrasound‐guided biopsy following a specified grid pattern of biopsies remains the standard of care. This approach misses 21% to 28% of prostate cancers. JAMA. 2017;317(24):2532‐2542. http://www.nature.com/nrurol/journal/v10/n12/abs/nrurol.2013.195.html Prostate Pathology Inflammation / granulomas Categories Adenosis, radiation, atrophy seminal vesicle Biopsy Benign TURP HGPIN Unsuspected carcinoma is seen in 12% of Atypical IHC TURP cases. glands Prostatectomy Subtype, Gleason, Malignant fat invasion, vascular invasion Other malignancies: sarcomas, lymphomas Benign Prostate Remember Malignant Glands Lack Basal Glands Cells Basal cells Secretory cells Stroma 2 7/12/2017 Benign Prostatic Lesions Atrophy Corpora amylacea (secretions) Seminal Vesicle Acute inflammation GMS Basal cell hyperplasia Basal cell hyperplasia Granulomas (BPH) (BPH) coccidiomycosis Mimics of Prostate Carcinoma Atrophy. Benign Carcinoma with atrophic features Prostate Carcinoma 1. Prostate cancer is the most common, noncutaneous cancer in men in the United States. -

The Role of Lymphadenectomy in Prostate Cancer Patients

Acta Clin Croat (Suppl. 1) 2019; 58:24-35 Professional paper doi: 10.20471/acc.2019.58.s2.05 THE ROLE OF LYMPHADENECTOMY IN PROSTATE CANCER PATIENTS Dean Markić1,2, Romano Oguić1,2, Kristian Krpina1, Ivan Vukelić1, Gordana Đorđević3,4, Iva Žuža5 and Josip Španjol1,2 1Department of Urology, University Hospital Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia; 2Department of Urology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia; 3Department of Pathology, University Hospital Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia; 4Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia; 5Department of Radiology, University Hospital Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia SUMMARY – Prostate cancer is one of the most important men’s health issues in developed countries. For patients with prostate cancer a preoperative staging of the disease must be made. In- volvement of lymph nodes could be assessed using imaging methods (CT or/and MRI), however, newer methods also exist (PET/CT, PSMA PET/CT). For some patients during radical prostatec- tomy a pelvic lymphadenectomy is recommended. Pelvic lymphadenectomy is indicated in intermedi- ate- and high-risk group patients and with increased probability of lymph node invasion. The most used prediction tools for preoperative assessment of lymph nodes are Briganti and MSKCC nomo- grams and Partin tables. Pelvic lymphadenectomy can include different lymph nodes group, but extended lymphadenectomy is the recommended procedure. In 1-20% of patients, the lymph node invasion is present. Pelvic lymphadenectomy is primarily a diagnostic and staging method, and in minority of patients with positive lymph nodes it can be a curative method, too. In other patients with positive lymph nodes adjuvant therapy (radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy) can be beneficial.