Insomnia and Identity: the Discursive Function of Sleeplessness in Modernist Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pierre Naville and the French Indigenization of Watson's Behavior

tapraid5/zhp-hips/zhp-hips/zhp99918/zhp2375d18z xppws Sϭ1 5/24/19 9:13 Art: 2019-0306 APA NLM History of Psychology © 2019 American Psychological Association 2019, Vol. 1, No. 999, 000–000 1093-4510/19/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/hop0000129 “The Damned Behaviorist” Versus French Phenomenologists: Pierre Naville and the French Indigenization of Watson’s Behaviorism AQ:1-3 Rémy Amouroux and Nicolas Zaslawski AQ: au University of Lausanne What do we know about the history of John Broadus Watson’s behaviorism outside of AQ: 4 its American context of production? In this article, using the French example, we propose a study of some of the actors and debates that structured this history. Strangely enough, it was not a “classic” experimental psychologist, but Pierre Naville (1904– 1993), a former surrealist, Marxist philosopher, and sociologist, who can be identified as the initial promoter of Watson’s ideas in France. However, despite Naville’s unwav- ering commitment to behaviorism, his weak position in the French intellectual com- munity, combined with his idiosyncratic view of Watson’s work, led him to embody, as he once described himself, the figure of “the damned behaviorist.” Indeed, when Naville was unsuccessfully trying to introduce behaviorism into France, alternative theories defended by philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Maurice Merleau-Ponty explic- itly condemned Watson’s theory and met with rapid and major success. Both existen- tialism and phenomenology were more in line than behaviorism with what could be called the “French national narrative” of the immediate postwar. After the humiliation of the occupation by the Nazis, the French audience was especially critical of any deterministic view of behavior that could be seen as a justification for collaboration. -

Intertextual Abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the Print, Politics, and Language of Slavery

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2019 Intertextual abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the print, politics, and language of slavery Jake Spangler DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Spangler, Jake, "Intertextual abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the print, politics, and language of slavery" (2019). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Intertextual Abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the Print, Politics, and Language of Slavery A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts June 2019 BY Jake C. Spangler Department of English College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois This project is lovingly dedicated to the memory of Jim Cowan Father, Friend, Teacher Table of Contents Dedication / i Table of Contents / ii Acknowledgements / iii Introduction / 1 I. “I Could Not Deem Myself a Slave” / 9 II. The Heroic Slave / 26 III. The “Files” of Frederick Douglass / 53 Bibliography / 76 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the support of several scholars and readers. -

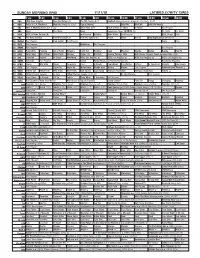

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Reading Group Guide

FONT: Anavio regular (wwwUNDER.my nts.com) THE DOME ABOUT THE BOOK IN BRIEF: The idea for this story had its genesis in an unpublished novel titled The Cannibals which was about a group of inhabitants who find themselves trapped in their apartment building. In Under the Dome the story begins on a bright autumn morning, when a small Maine town is suddenly cut off from the rest of the world, and the inhabitants have to fight to survive. As food, electricity and water run short King performs an expert observation of human psychology, exploring how over a hundred characters deal with this terrifying scenario, bringing every one of his creations to three-dimensional life. Stephen King’s longest novel in many years, Under the Dome is a return to the large-scale storytelling of his ever-popular classic The Stand. IN DETAIL: Fast-paced, yet packed full of fascinating detail, the novel begins with a long list of characters, including three ‘dogs of note’ who were in Chester’s Mill on what comes to be known as ‘Dome Day’ — the day when the small Maine town finds itself forcibly isolated from the rest of America by an invisible force field. A woodchuck is chopped right in half; a gardener’s hand is severed at the wrist; a plane explodes with sheets of flame spreading to the ground. No one can get in and no one can get out. One of King’s great talents is his ability to alternate between large set-pieces and intimate moments of human drama, and King gets this balance exactly right in Under the Dome. -

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101 an International Refereed E-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.793 (IIFS)

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101 www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.793 (IIFS) DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN STEPHEN KING’S ROSE MADDER Nitasha Baloria Ph.D. Research Scholar Department of English University of Jammu Jammu- 180001 (J&K) Abstract I read it somewhere, “You’ve given him the benefit of the doubt long enough. Now it’s time to give yourself the benefit of the truth.” Marriages have not been a cup of tea for everyone. You are lucky enough if your marriage is a loving one but not everyone is as lucky. Sometimes the wrong marriages or our wrong partners force us to think that it wasn’t a cakewalk, especially when the matter is of DOMESTIC VIOLENCE. As painful as it is to admit that we are being abused, it is even more painful to come to the conclusion that the person we love is someone we cannot afford to be around. This research paper will focus on the theme of Domestic Violence in the novel of Stephen King’s ROSE MADDER. It focuses on the main protagonist Rosie’s life. How She escapes from her eccentric husband and then makes a path to overcome her fear for her husband, leaves him and finally live a happy Life marrying the right person. Keywords:- Domestic Violence, eccentric, wrong Marrieage. “All marriages are sacred, but not all are safe.” - Rob Jackson This paper entitled, “ Domestic Violence in Stephen King’s Rose Madder” aims to explore the life of a young woman named Rosie who is married and is being tortured by her husband by consistent beating. -

The Holocaust in French Film : Nuit Et Brouillard (1955) and Shoah (1986)

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2008 The Holocaust in French film : Nuit et brouillard (1955) and Shoah (1986) Erin Brandon San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Brandon, Erin, "The Holocaust in French film : Nuit et brouillard (1955) and Shoah (1986)" (2008). Master's Theses. 3586. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.y3vc-6k7d https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3586 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOLOCAUST IN FRENCH FILM: NUITETBROUILLARD (1955) and SHOAH (1986) A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Erin Brandon August 2008 UMI Number: 1459690 Copyright 2008 by Brandon, Erin All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1459690 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. -

Work/Construction Zones

Work/Construction Zones Page 1 of 2 A work zone is an area where roadwork takes place and may involve lane closures, detours and moving equipment. Highway work zones are set up according to the type of road and the work to be done on the road. The work zone can be long or short term and can exist at anytime of the year, but most commonly in the summer. Work zones on U.S. highways have become increasingly dangerous places for both workers and drivers. There are a large number of work zones in place across America, therefore, highway agencies are working on not only improving communication used in work zones, but to change the behavior of drivers so crashes can be prevented. According to the National Safety Council, over 100 road construction workers are killed in construction zones each year. Nearly half of these workers are killed as a result of being struck by motor vehicles. The number of construction zone injuries and fatalities are predicted to climb even higher. Increased funding for road construction during recent years has led to a significant increase in the number of highway construction projects around the country. Increased speed limits, impatient drivers, and widespread traffic congestion have led to an overall increase in work zone injuries and fatalities. The top 10 states with motorist fatalities in work zones in 2008 are as follows: 1. Texas—134 6. Pennsylvania—23 2. Florida—81 7. Louisiana—22 3. California—70 8. North Carolina—21 4. Georgia—36 9. Arkansas—19 5. Illinois—31 Source: FARS 10. -

Novel Non-Pharmacological Insomnia Treatment – a Pilot Study

Nature and Science of Sleep Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Novel non-pharmacological insomnia treatment – a pilot study This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: Nature and Science of Sleep Milena K Pavlova1 Objective: The objective of this prospective pilot study was to examine the effects of a Véronique Latreille1 novel non-pharmacological device (BioBoosti) on insomnia symptoms in adults. Nirajan Puri1 Methods: Subjects with chronic insomnia were instructed to hold the device in each hand Jami Johnsen1 for 8 mins for 6 cycles on a nightly basis for 2 weeks. Outcomes tested included standardized Salma Batool-Anwar2 subjective sleep measures assessing sleep quality, insomnia symptoms, and daytime sleepi- ness. Sleep was objectively quantified using electroencephalogram (EEG) before and after 2 Sogol Javaheri2 weeks of treatment with BioBoosti, and wrist actigraphy throughout the study. Paul G Mathew1 Results: Twenty adults (mean age: 45.6±17.1 y/o; range 18–74 y/o) were enrolled in the 1Department of Neurology, Harvard study. No significant side effects were noted by any of the subjects. After 2 weeks of Medical School, Brigham and Women’s BioBoosti use, subjects reported improved sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; 2Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, 12.6±3.3 versus 8.5±3.7, p=0.001) and reduced insomnia symptoms (Insomnia Severity Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Index: 18.2±5.2 versus 12.8±7.0, p<0.001). Sleepiness, as assessed by a visual analog For personal use only. -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci Filozofická Fakulta

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA KATEDRA ANGLISTIKY A AMERIKANISTIKY Veronika Glaserová The Importance and Meaning of the Character of the Writer in Stephen King’s Works Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Matthew Sweney, Ph.D. Olomouc 2014 Olomouc 2014 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem předepsaným způsobem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne Podpis: Poděkování Děkuji vedoucímu práce za odborné vedení práce, poskytování rad a materiálových podkladů k práci. Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6 1. Genres of Stephen King’s Works ................................................................................. 8 1.1. Fiction .................................................................................................................... 8 1.1.1. Mainstream fiction ........................................................................................... 9 1.1.2. Horror fiction ................................................................................................. 10 1.1.3. Science fiction ............................................................................................... 12 1.1.4. Fantasy ........................................................................................................... 14 1.1.5. Crime fiction ................................................................................................. -

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands Wizard and Glass www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End of Watch Short -

Jean-Paul Sartre

From the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy Jean-Paul Sartre Christina Howells Biography Sartre was a philosopher of paradox: an existentialist who attempted a reconciliation with Marxism, a theorist of freedom who explored the notion of predestination. From the mid-1930s to the late-1940s, Sartre was in his ‘classical’ period. He explored the history of theories of imagination leading up to that of Husserl, and developed his own phenomenological account of imagination as the key to the freedom of consciousness. He analysed human emotions, arguing that emotion is a freely chosen mode of relationship to the outside world. In his major philosophical work, L’Être et le Néant (Being and Nothingness)(1943a), Sartre distinguished between consciousness and all other beings: consciousness is always at least tacitly conscious of itself, hence it is essentially ‘for itself’ (pour-soi) – free, mobile and spontaneous. Everything else, lacking this self-consciousness, is just what it is ‘in-itself’ (en-soi); it is ‘solid’ and lacks freedom. Consciousness is always engaged in the world of which it is conscious, and in relationships with other consciousnesses. These relationships are conflictual: they involve a battle to maintain the position of subject and to make the other into an object. This battle is inescapable. Although Sartre was indeed a philosopher of freedom, his conception of freedom is often misunderstood. Already in Being and Nothingness human freedom operates against a background of facticity and situation. My facticity is all the facts about myself which cannot be changed – my age, sex, class of origin, race and so on; my situation may be modified, but it still constitutes the starting point for change and roots consciousness firmly in the world. -

Sinner to Saint

FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 4, 2017 7:23:54 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of November 11 - 17, 2017 OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Sinner to saint FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Kimberly Hébert Gregoy and Jason Ritter star in “Kevin (Probably) Saves the World” Massachusetts’ First Credit Union In spite of his selfish past — or perhaps be- Located at 370 Highland Avenue, Salem John Doyle cause of it — Kevin Finn (Jason Ritter, “Joan of St. Jean's Credit Union INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY Arcadia”) sets out to make the world a better 3 x 3 Voted #1 1 x 3 place in “Kevin (Probably) Saves the World,” Serving over 15,000 Members • A Part of your Community since 1910 Insurance Agency airing Tuesday, Nov. 14, on ABC. All the while, a Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs celestial being known as Yvette (Kimberly Hé- bert Gregory, “Vice Principals”) guides him on Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses Auto • Homeowners his mission. JoAnna Garcia Swisher (“Once 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com Business • Life Insurance Upon a Time”) and India de Beaufort (“Veep”) Offices also located in Lynn, Newburyport & Revere 978-777-6344 also star. Federally Insured by NCUA www.doyleinsurance.com FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 4, 2017 7:23:55 PM 2 • Salem News • November 11 - 17, 2017 TV with soul: New ABC drama follows a man on a mission By Kyla Brewer find and anoint a new generation the Hollywood ranks with roles in With You,” and has a recurring role ma, but they hope “Kevin (Proba- TV Media of righteous souls.