The Magical Nature of Social Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An N U Al R Ep O R T 2018 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 ANNUAL REPORT The Annual Report in English is a translation of the French Document de référence provided for information purposes. This translation is qualified in its entirety by reference to the Document de référence. The Annual Report is available on the Company’s website www.vivendi.com II –— VIVENDI –— ANNUAL REPORT 2018 –— –— VIVENDI –— ANNUAL REPORT 2018 –— 01 Content QUESTIONS FOR YANNICK BOLLORÉ AND ARNAUD DE PUYFONTAINE 02 PROFILE OF THE GROUP — STRATEGY AND VALUE CREATION — BUSINESSES, FINANCIAL COMMUNICATION, TAX POLICY AND REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT — NON-FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE 04 1. Profile of the Group 06 1 2. Strategy and Value Creation 12 3. Businesses – Financial Communication – Tax Policy and Regulatory Environment 24 4. Non-financial Performance 48 RISK FACTORS — INTERNAL CONTROL AND RISK MANAGEMENT — COMPLIANCE POLICY 96 1. Risk Factors 98 2. Internal Control and Risk Management 102 2 3. Compliance Policy 108 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE OF VIVENDI — COMPENSATION OF CORPORATE OFFICERS OF VIVENDI — GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE COMPANY 112 1. Corporate Governance of Vivendi 114 2. Compensation of Corporate Officers of Vivendi 150 3 3. General Information about the Company 184 FINANCIAL REPORT — STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT ON THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — STATUTORY FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 196 Key Consolidated Financial Data for the last five years 198 4 I – 2018 Financial Report 199 II – Appendix to the Financial Report 222 III – Audited Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2018 223 IV – 2018 Statutory Financial Statements 319 RECENT EVENTS — OUTLOOK 358 1. Recent Events 360 5 2. Outlook 361 RESPONSIBILITY FOR AUDITING THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 362 1. -

Beggar and King

BEGGAR AND KING BEGGAR AND KING BY RICHARD BUTLER GLAENZER NEW HAVEN: YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON: HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MDCCCCXVII COPYRIGHT. 1917 BY YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS First published. October, 1917 PS Acknowledgment is made, with thanks, to Adventure, Ainslee s Magazine, The American Magazine, The Book man, The Boston Transcript, The Century Magazine, The Forum, Harper s Weekly, The International, Life, Metro politan, Munsey s Magazine, The New York Evening Sun, The New York Times, The Outlook (London), The Phcenix, Poet Lore, Poetry, Poetry Review (London), Rogue, The Royal Bermuda Gazette, The Smart Set, Town Topics and other magazines for permission to reprint such of the following as have appeared in their pages. 612853 LIBRARY TO MY MOTHER WHOM LOVE AND SELF-DENIAL HAVE LIFTED TO HEIGHTS BEYOND THE POWERS OF TRIBUTE My brain F II prove the female to my soul, My soul the father; and these two beget A generation of still-breeding" thoughts, And these same thoughts people this little -world In humours like the people of this world. Thus play I in one person many people, And none contented: sometimes am I king; Then treasons make me wish myself a beggar, And so I am: then crushing penury Persuades me I was better when a king; Then am I king d again. Whatever I be, Nor I nor any man that but man is With nothing shall be pleased, till he be eased With being nothing. KING RICHARD II, Act V, Scene 5. CONTENTS PAGE Masters of Earth 1 The East and the West : Buddha 3 Mater Dolorosa 4 The Wolf 5 Measure for Measure 6 A Twilight Impression 8 Ballade of Perfumes 9 Parabalou . -

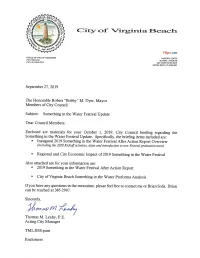

SITW After Action Report

Inaugural 2019 Something in the Water Festival After Action Report Overview Brian S. Solis, AICP Assistant to the City Manager – Special Projects October 1, 2019 1 Pharrell Williams announced concept of Something in the Water Festival on 10/28/18 3/8/19 - 25,000 tickets sold out in 21 minutes 3/27/19 - Festival capacity increased to 35,000 tickets Sold out for a final time on 3/27/19, one month ahead of the Festival Friday, 4/26/19 main stage performances cancelled due to inclement weather (ticket purchasers refunded 33% of ticket price) Saturday, 4/27/19 main stage area peak scanned attendance in 34,700 range Sunday, 4/28/19 main stage area peak scanned attendance in 27,000 range 2 5th St. Stage Pop Up Church @ 20th St. on the Friday 2 pm – 11 pm (cancelled) Beach Saturday Noon – 11 pm (12:30 am) Sunday only Noon to 9:00 pm Sunday Noon – 10 pm (10:15 pm) Sony @ 19th St. and Pacific Ave. Convention Center - Separate detail Friday 2 pm – 11 pm Saturday Noon – 11 pm Adidas @ 24th St. Park Sunday Noon – 8 pm Friday 9 am – 7:30 pm (closed periodically due to weather) Timberland @ 17th St. and Pacific Saturday 9 am – 7:30 pm Ave. Friday Noon – 11 pm Array @ 31st St. Park Saturday 2pm – 11 pm (moved to MOCA due Sunday 2 pm – 11 pm to inclement weather) Movie Screening Friday only 7 pm – 11 pm 3 4 Something in the Water Festival Milestones and Activities 10/28/19 Mr. Williams announced concept of Festival to be held during the CBW 11/13/18 Initial City Council briefing to proceed with Festival 3/5/19 City Council authorized $250,000 and in-kind -

From No Future to Delete Yourself (You Have No Chance to Win)

Journal of Popular Music Studies, Volume 25, Issue 4, Pages 504–536 From “No Future” to “Delete Yourself (You Have No Chance to Win)”: Death, Queerness, and the Sound of Neoliberalism Robin James University of North Carolina, Charlotte Introduction Death is one of the West’s oldest philosophical problems, and it has recently been the focus of heated debates in queer theory. These debates consider the political and aesthetic function of a specific concept of death— death as negation, failure, an-arche, or creative destruction. However, as Michel Foucault (1990) argues, death is an important component of the discourse of sexuality precisely because it isn’t a type of negation. The discourse of sexuality emerges when “the ancient right to take life or let live was,” he argues, “replaced by a power to foster life or disallow it to the point of death” (Foucault 138).1 “Sexuality is the heart and lifeblood of biopolitics” (Winnubst 2012: 79) because it—or rather, as other scholars like Laura Ann Stoler (1995), LaDelle McWhorter (2009), and Jasbir Puar (2013) have demonstrated, racialized sexuality—is one of the main instruments through which liberalism “fosters” or “disallows” life. So, insofar as it pertains to sexuality, death isn’t a negation or a subtraction of life, but a side effect of a particular style of life management. In late capitalist neoliberalism, “death” only appears indirectly, not as a challenge to or interruption of life, but as its unthinkable, imperceptible limit.2 What are the theoretical, political, and aesthetic implications of neoliberalism’sreconceptualization of death as divested, or “bare,” life?3 What if we reframe ongoing debates about queer death, futurity, and antisociality by replacing the punk metaphorics of “No Future” with the cyberpunk/digital hardcore mantra “Delete Yourself (You Have No Chance To Win)”? Asking the question in this way, I use some methods, concepts, and problems from queer theory to think about a few pieces of music; I then use my analyses of these musical works to reflect back on that theory. -

Class Founds Award Graham Shirley and Sheila Venable

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Student Newspaper (Amicus, Advocate...) Archives and Law School History 1987 The Advocate (Vol. 18, Issue 12) Repository Citation "The Advocate (Vol. 18, Issue 12)" (1987). Student Newspaper (Amicus, Advocate...). 167. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/newspapers/167 Copyright c 1987 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/newspapers 'volume XVllI, Number 12 Eight Pages The Advocate The AMERICA'S OLDEST LAW SCHOOL ~v()ca e Marshall-Wythe Sch ool of Law F O l:~DED 1779 Libel Night '87 Blasi Expounds on First Amendment the truth or free speech as a step the "subjectivism of the actual to the truth. Rather, this political malice standard. It mandates get By Phillip Steele truth is that "the final end of the ting into the mind of the reporter, state is to serve the people. And a and can involve intrusive Reminding us that "public happy person is one who draws on discovery. " discussion is an imperative to the courage to think as you will and Another troubling aspect for preservation of freedom," Pro speak as you think." . Blasi is the extension of the actual fessor Vincent Blasi expounded Though never defining it, the malice principle to public figures. the virtues of the First Amend "courage" Blasi alluded to is the He stated this can be used to pro ment while visiting Marshall willingness to let others speak tect people who do not really exer Wythe last week as a Cutler their minds even when the majori cise power and have not thrust Lecturer. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

Crinew Music Re Uoft

CRINew Music Re u oft SEPTEMBER 11, 2000 ISSUE 682 VOL. 63 NO. 12 WWW.CMJ.COM MUST HEAR Universal/NIP3.com Trial Begins With its lawsuit against MP3.com set to go inent on the case. to trial on August 28, Universal Music Group, On August 22, MP3.com settled with Sony the only major label that has not reached aset- Music Entertainment. This left the Seagram- tlement with MP3.com, appears to be dragging owned UMG as the last holdout of the major its feet in trying to reach a settlement, accord- labels to settle with the online company, which ing to MP3.com's lead attorney. currently has on hold its My.MP3.com service "Universal has adifferent agenda. They fig- — the source for all the litigation. ure that since they are the last to settle, they can Like earlier settlements with Warner Music squeeze us," said Michael Rhodes of the firm Group, BMG and EMI, the Sony settlement cov- Cooley Godward LLP, the lead attorney for ers copyright infringements, as well as alicens- MP3.com. Universal officials declined to corn- ing agreement allowing (Continued on page 10) SHELLAC Soundbreak.com, RIAA Agree Jurassic-5, Dilated LOS AMIGOS INVIWITI3LES- On Webcasting Royalty Peoples Go By Soundbreak.com made a fast break, leaving the pack behind and making an agreement with the Recording Word Of Mouth Industry Association of America (RIAA) on aroyalty rate for After hitting the number one a [digital compulsory Webcast license]. No details of the spot on the CMJ Radio 200 and actual rate were released. -

Pharrell Williams

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Media Company Leader Presentations School of Media and Communication Spring 2018 i am OTHER: Pharrell Williams Renei Jackson Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/mclp Recommended Citation Jackson, Renei, "i am OTHER: Pharrell Williams" (2018). Media Company Leader Presentations. 9. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/mclp/9 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Media and Communication at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Company Leader Presentations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. i am OTHER Pharrell Williams A Presentation by Renei Jackson Background • Pharrell Lanscilo Williams was born on April 5, 1973 in the city of Virginia Beach, VA • He grew up being “the problem child” at school always making beats on the tables and being sent to detention. • He was born in a predominantly African-American community as a child where he didn’t really fit in because of his mix of inspiration from skaters such as Tony Hawk and Christian Hosoi to renown hip hop artists Dougie Fresh and Slick Rick. • His family later moved to the suburbs where he was surrounded by a primarily White community. Being involved in different environments made him depend on music to connect to other people. Transition into Fame • He first came into fame as a songwriting and production duo, Neptune, with his friend Chad Hugo in the 90s. • They produced hits for artists ranging from Jay-Z to Britney Spears. He produced some artists most well known songs such as Nelly’s “Hot in Herre,” Gwen Stefani’s “Hollaback Girl”, Kelis’ “My Milkshake Brings All the Boys to the Yard,” and Justin Timberlake’s “Senorita.” • In a study done by Complex, during 2003, The Neptunes were responsible for 43% of the songs playing on the radio in the United States. -

Pharrell Williams, ‘Freedom’ - Factsheet

Pharrell Williams, ‘Freedom’ - Factsheet Pharrell Williams, ‘Freedom’ (2015) https://youtu.be/LlY90lG_Fuw Subject content focus area Media language Representation Media Industries Audiences Contexts Background context • ‘Freedom’ was released in 2015, two years after Pharrell Williams’ previous global hit ‘Happy’. The video was directed by Paul Hunter and was nominated for Best Music Video at the 2016 Grammy Awards. • Pharrell has a long history in the music business, beginning with hip-hop production duo The Neptunes and hip-hop-rock band N*E*R*D in the 90s, then a successful solo career in the 2000s. He has also written and produced music for artists such as Ariana Grande. • Pharrell Williams is what is termed a ‘Renaissance Man’ - someone who is highly talented in a number of different areas. He has an ‘umbrella brand’ called i am OTHER which incorporates Pharrell’s fashion labels, movie production company, record label, and social activism initiatives. In the concept, photography and design of the video for ‘Freedom’ we can see these elements combined. • The celebration of racial and cultural diversity seen in the video could be a response to controversy over Pharrell’s earlier comments about the ‘New Black’ and race relations in America. In 2013, demonstrations took place in the USA to protest about violence towards black people, and the Black Lives Matter movement was established. (There had been several cases of unarmed black people being killed by police officers in the USA.) The link below shows Pharrell Williams explaining his views in more detail: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iMmXC_MgHlc Part 1: Starting points - Media language • The video is a good example of montage editing, where a number of seemingly unconnected images are cut together to suggest a theme or create a specific emotional reaction. -

The Meaning of Velvet Jennifer Jean Wright Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 The meaning of velvet Jennifer Jean Wright Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Jennifer Jean, "The meaning of velvet" (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16209. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16209 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The meaning of velvet by Jennifer Jean Wright A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Creative Writing) Major Professor: Stephen Pett Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2000 Copyright © Jennifer Jean Wright, 2000. All rights reserved. iii that's the girl that he takes around town. she appears composed, so she is I suppose, who can really tell? she shows no emotion at all stares into space like a dead china doll. --Elliot Smith, waltz #2 The ashtray says you were up all night when you went to bed with your darkest mind your pillow wept and covered your eyes you finally slept while the sun caught fire You've changed. --Wilco, a shot in the arm two headed boy all floating in glass the sun now it's blacker then black I can hear as you tap on your jar I am listening to hear where you are .. -

Ivan Muñoz Aka Vigilante Is One of the Most Important Electronic Music Artists & Djs in South America

Ivan Muñoz aka Vigilante is one of the most important electronic music artists & Djs in South America. With his mix of electronic and metal, Muñoz has conquered audiences from Chile and all over the world. He has released three albums: "The Heroes Code" (2005), "War of Ideas" (2007), and “The New Resistance” (2011), one EP "Juicio Final" (2006); one DVD + CD "Life is a Battlefield" (2009) and several singles in countries as diverse as Germany, Russia, Chile, Argentina and Japan. His records are distributed both physically and digitally throughout the world. With 6 international tours, Vigilante has brought his music to many countries: United States, Russia, Germany, Netherlands, Peru, Argentina, Chile, Czech Republic, Poland, Denmark, Belgium, France, Portugal, Switzerland, Italy, Norway, Spain, and many more. In addition, he has been the only Chilean musician to participate in some of the more important Festivals in Europe, like Wave Gotik Treffen (Germany, 2006 and 2010), Castle Party (Poland, 2012); and in 2008 Vigilante was the support band of the Industrial legends Nine Inch Nails. Throughout his career, he has worked, remixed and shared stage with the most important bands in the scene such as: Nine Inch Nails, Lacrimosa, Ministry, Strapping Young Lad, Public Enemy, Suicide Commando, S.I.T.D., Die Krupps, VNV Nation, Funker Vogt, Leaether Strip, Agonoize, Soman, Hocico, Birmingham 6, Hanin Elias, Tyske Ludder, Clan of Xymox and many more. His profesionalism and talent made him being endorsed by the most important brands in the music industry like Focusrite, Novation, Schecter, Fxpansion, Presonus, Seymour Duncan, Sony Creative Software and many more. -

![57 Brief Summary of Responses Based on 3 Themes ("Slimming Equals […]")](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4389/57-brief-summary-of-responses-based-on-3-themes-slimming-equals-1704389.webp)

57 Brief Summary of Responses Based on 3 Themes ("Slimming Equals […]")

SUMMARY OF INTERPRETATION OF THE INTERVIEWS: RESPONDENTS 5 – 57 Brief Summary of Responses Based on 3 Themes ("Slimming equals […]") Themes Beauty/Attractiveness/Desirability/ Confidence Sexual Appeal Social Upward Mobility/ Success in Life Respondents i think is very important, because if I [am] really Men is always looking for beautiful things.[...] Ah because I’m in sales, […] it’s actually very important really obese right, I don’t feel that I’m not But at least you have to take care of yourself for your figure to look slim [...]client is always like this, energetic, I don’t feel that I can actually approach la…as a women.[…] Men are always men. Men […] they always look at the beautiful things. […] it’s people. [...] Self confidence ah….i think is very is always looking for beautiful things. Even actually very important for your figure to look slim, important, because if I really really obese right, I though they mentions that oh, I would not mind, instead of like, you know, out of proportion, like, you don’t feel that I’m not energetic, I don’t feel that I regardless you like, round, know, here fat there fat, taking care of your own health, can actually approach people. You fat…so…..fat…fat…obese la eh..[laughter] you your own figure, look nice, in order to … client is always know..like…ah…in..like..convince know, but in their hearts o..don’t mean you like this, you know… they always look at the beautiful people..ya..because it’s like…you know, obese…I always look at those la, very down things, round things don’t know…I always have that kind of attitude, things like that..you know, like obese, it’s like, you know, it’s always a bit in my mind like if boring…nothing as the first attraction.