Chivalry and Knighthood in England, 1327-77

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pythian International

Page 12 Supreme Lodge Knights of Pythias The New 1 2013 Supreme Lodge Poster Contest Winners Pythian International PUBLISHED BY THE SUPREME LODGE, KNIGHTS OF PYTHIAS VOLUME I No. 2 SUMMER/FALL 2013 Grand Lodge Conventions Summer/Fall 2013 Maryland September 5-7 Ocean City 1st Place Poster, winner of $1,000.00 2nd Place Poster - winner of $500.00 3rd Place Poster - winner of $250.00 New Mexico September 6-7 Lordsburg Ariana Quintero - 12th Grade Jane Harmsworth - 11th Grade Zach Knisley - 12th Grade Desert Edge High School Mark R. Isfeld Secondary School Springfield, Ohio Illinois September 12-13 Goodyear, Arizona, 85338 Courtenay, BC, Canada V9N 2T8 Peoria Nevada September 18-21 Listed below are 4th thru 8th place (winners of $100 each) Henderson A Message from Ohio September 18-21 Columbus 4th Place Poster (At Large Submission) 7th Place Poster (At Large Submission) The Supreme Chancellor North Carolina September 19-22 Sabrina Leal - 11th Grade Elizabeth Crisler - 12th Grade Myrtle Beach Nogales High School Ambassadors for Christ Academy Michigan September 20-21 Nogales, Arizona, 85621 Bella Vista, AR 72715 Dear Pythian Family : Lansing Welcome to the second edition of The Pythian In- 5th Place Poster 8th Place Poster Washington September 20-22 ternational. I trust you had a pleasant summer. Yakima Amanda Bevilacqua - 12th Grade Alyssa Gallagher - 12th Grade With the absence of a Domain in Ontario Canada, I Downingtown West High School Manchester West High School Colorado/Wyoming September 20-21 am pleased to welcome two new Subordinate Downingtown, Pennsylvania Manchester, NH 03102 Cheyenne, WY Lodges in Ontario, they will be under the jurisdic- tion of Michigan. -

KNIGHTS of COLUMBUS Msgr

KNIGHTS OF COLUMBUS Msgr. James Corbett Warren Memorial Council 5073 2400 Industrial Street, Burlington, Ontario L7P 1A5 905-335-5073 t email: [email protected] website: www.kofc5073.ca NEWSLETTER June 2016 Msgr. J. C. Warren COUNCIL EXECUTIVE 2015-2016 A Message from our Grand Knight CHAPLAIN Fr. Ronald Hodara John D’Addario GRAND KNIGHT John D’Addario 905.639.9727 DEPUTY GRAND KNIGHT Kevin Abraham 905.330.7545 CHANCELLOR Brothers, Michael Mark 905.333.3623 RECORDER The end of a Fraternal year should not be looked at as a sad and negative Bill Manley event. It should be looked at as the end of a chapter in a book that you are 905.632.7410 FINANCIAL SECRETARY currently reading and just do not want to put down. It is a great book about Paul Catena a council that has been around since 1960 with members who give their time 905.630.1840 to strengthen four parish communities in a great city called Burlington. What TREASURER Jim Csordas is the name of this book ? It could be called “Monsignor James Warren 905.681.2075 Memorial Council 5073.” The completion of this Fraternal year marks the LECTURER 56th chapter of the book. Many accomplishments and loads of stories and Frank Miele 416.606.0436 good deeds have been documented in the book to date. The writing of the ADVOCATE 57th chapter starts on July 1, and together we can write a chapter that will Jim Csordas truly show Brother Knights in the future that we stand by our motto “In 905.681.2075 WARDEN Service to One, In Service to All.” In the months ahead, please share your Michael Attardo ideas with your Brother Knights, get involved, and remember that someone 905.635.8775 thought very highly of you to invite you to join the Knights of Columbus. -

Daisy Badges & Journeys

NATIONAL PROFICIENCY BADGES Badge Category Daisy Brownie Junior Cadette Senior Ambassador Animals Pets Animal Habitats Animal Helpers Voice for Animals Coding for Good I Coding Basics Coding Basics Coding Basics Coding Basics Coding Basics Coding Basics Coding for Good II Digital Game Design Digital Game Design Digital Game Design Digital Game Design Digital Game Design Digital Game Design Coding for Good III App Development App Development App Development App Development App Development App Development Cybersecurity I Cybersecurity Basics Cybersecurity Basics Cybersecurity Basics Cybersecurity Basics Cybersecurity Basics Cybersecurity Basics Cybersecurity II Cybersecurity Safeguards Cybersecurity Safeguards Cybersecurity Safeguards Cybersecurity Safeguards Cybersecurity Safeguards Cybersecurity Safeguards Cybersecurity III Cybersecurity Investigator Cybersecurity Investigator Cybersecurity Investigator Cybersecurity Investigator Cybersecurity Investigator Cybersecurity Investigator Digital Arts Computer Expert Digital Photographer Digital Movie Maker Website Designer Investigation Senses Detective Special Agent Truth Seeker Mechanical Engineering I Board Game Design Challenge Leap Bot Design Challenge Paddle Boat Design Challenge Roller Coaster Design Mechanical Engineering II Fling Flyer Design Challenge Balloon Car Design Challenge Challenge Mechanical Engineering III Model Car Design Challenge Race Car Design Challenge Crane Design Challenge Robotics I What Robots Do Programming Robots Programming Robots Programming Robots Programming -

Master Narrative Ours Is the Epic Story of the Royal Navy, Its Impact on Britain and the World from Its Origins in 625 A.D

NMRN Master Narrative Ours is the epic story of the Royal Navy, its impact on Britain and the world from its origins in 625 A.D. to the present day. We will tell this emotionally-coloured and nuanced story, one of triumph and achievement as well as failure and muddle, through four key themes:- People. We tell the story of the Royal Navy’s people. We examine the qualities that distinguish people serving at sea: courage, loyalty and sacrifice but also incidents of ignorance, cruelty and cowardice. We trace the changes from the amateur ‘soldiers at sea’, through the professionalization of officers and then ships’ companies, onto the ‘citizen sailors’ who fought the World Wars and finally to today’s small, elite force of men and women. We highlight the change as people are rewarded in war with personal profit and prize money but then dispensed with in peace, to the different kind of recognition given to salaried public servants. Increasingly the people’s story becomes one of highly trained specialists, often serving in branches with strong corporate identities: the Royal Marines, the Submarine Service and the Fleet Air Arm. We will examine these identities and the Royal Navy’s unique camaraderie, characterised by simultaneous loyalties to ship, trade, branch, service and comrades. Purpose. We tell the story of the Royal Navy’s roles in the past, and explain its purpose today. Using examples of what the service did and continues to do, we show how for centuries it was the pre-eminent agent of first the British Crown and then of state policy throughout the world. -

Merits of Invention Edition

Vol. 7, No. 11 MERITS OF INVENTION EDITION In this Issue: • The Last Inventor • Merit Badge Sashes • Earning Them All • Reinventing the Invention Merit Badge • Thomas Edison and Scouting • Thomas Edison Supernova Award “Build a better mousetrap,” goes an old saying, “and the world will beat a pathway to your door.” That’s all good, unless you happen to be a mouse. Inventing things captures the imagination of young people. Find some tools, boards, pipes, wires, and before long they are nailing, pounding, shaping, bolting, gluing, and imagining what to make next. It’s an impulse Scouting has encouraged since the BSA’s earliest days. THE LAST INVENTOR This year marks a tiny Scouting anniversary. A hundred years ago in 1915, exactly one person earned the Invention merit badge. He was also the tenth and last to receive what has become the BSA’s least-earned award and rarest embroidered patch. Invention was one of the original 57 merit badges listed in the 1911 Boy Scout Handbook. It had just two requirements. Inventing something is one thing. Getting it patented is quite another. To protect an invention from use by others without permission, an inventor must file with the United States Office of Patents and Trademarks and then wait to learn if a patent has been granted. Many early BSA emblems show evidence of being patented. A Scout who did earn the Invention merit badge was Graeme Smallwood of Troop 32, Washington, DC. It was his 38th merit badge. He filed for his patent on October 27, 1914, and received it thirteen months later on the last day of November, 1915. -

The Condition of the Working-Class in England, 1209-20031

The Condition of the Working-Class in England, 1 1209-2003 Gregory Clark Department of Economics UC-Davis, Davis CA 95616 [email protected] The paper estimates both the real wages of male building craftsmen and laborers in England for 1209-2003, and the wage premium associated with skills. These estimates have implications for our understanding of both the Malthusian era, and of the Industrial Revolution. They reveal, for example, that from 1200 until 1800 there was no trend increase in real wages, even though by 1800 English workers were probably the best paid in the world. There was a period of as long as 350 years with no evidence of TFP growth. But they also imply that modern economic growth, fuelled by productivity advance, probably began in the seventeenth century before the institutional reforms of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Finally these estimates suggest that human capital interpretations of the Industrial Revolution, formalized by Becker et al. (1990), Galor and Weil (2000) and Lucas (2002), as presently constructed, conflict with the empirical record. Human capital accumulation in England began in an era when the market rewards to skill acquisition had fallen substantially from their medieval peak. Introduction Pre-industrial England has a uniquely well documented wage and price history. The stability of English institutions after 1066, and the early development of monetary exchange, allowed a large number of documents with wages and prices to survive in the records of churches, monasteries, colleges, craft guilds, charities, and local and national governments. This 1 The author owes an enormous debt to the many transcribers and compilers of English wage data, some of whom are listed below in footnote 2. -

Reputation Systems for Anonymous Networks

Reputation Systems for Anonymous Networks Elli Androulaki, Seung Geol Choi, Steven M. Bellovin, and Tal Malkin Department of Computer Science, Columbia University {elli,sgchoi,smb,tal}@cs.columbia.edu Abstract. We present a reputation scheme for a pseudonymous peer-to-peer (P2P) system in an anonymous network. Misbehavior is one of the biggest prob- lems in pseudonymous P2P systems, where there is little incentive for proper behavior. In our scheme, using ecash for reputation points, the reputation of each user is closely related to his real identity rather than to his current pseudonym. Thus, our scheme allows an honest user to switch to a new pseudonym keeping his good reputation, while hindering a malicious user from erasing his trail of evil deeds with a new pseudonym. 1 Introduction Pseudonymous System. Anonymity is a desirable attribute to users (or peers) who par- ticipate in peer-to-peer (P2P) system. A peer, representing himself via a pseudonym, is free from the burden of revealing his real identity when carrying out transactions with others. He can make his transactions unlinkable (i.e., hard to tell whether they come from the same peer) by using a different pseudonym in each transaction. Com- plete anonymity, however, is not desirable for the good of the whole community in the system: an honest peer has no choice but to suffer from repeated misbehaviors (e.g. sending an infected file to others) of a malicious peer, which lead to no consequences in this perfectly pseudonymous world. Reputation System. We present a reputation system as a reasonable solution to the above problem. -

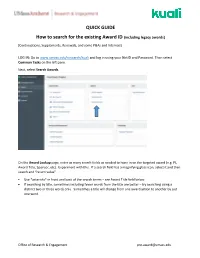

QUICK GUIDE How to Search for the Existing Award ID (Including Legacy

QUICK GUIDE How to search for the existing Award ID (including legacy awards) (Continuations, Supplements, Renewals, and some P&As and Internals) LOG IN: Go to www.umass.edu/research/kuali and log in using your NetID and Password. Then select Common Tasks on the left pane. Next, select Search Awards. On the Award Lookup page, enter as many search fields as needed to hone in on the targeted award (e.g. PI, Award Title, Sponsor, etc). Experiment with this. If a search field has a magnifying glass icon, select it and then search and “return value”. • Use *asterisks* in front and back of the search terms – see Award Title field below. • If searching by title, sometimes including fewer words from the title are better – try searching using a distinct two or three words only. Sometimes a title will change from one award action to another by just one word. Office of Research & Engagement [email protected] • After searching, run a report by selecting spreadsheet (seen below this chart on the left). Suggestions: Save as an Excel Workbook when multiple award records appear in order to hone in on the correct version. Delete columns as needed and add a filter to help with the sort and search process. Office of Research & Engagement [email protected] Identify the correct award Always select the so-called “Parent” award – the suffix is always “-00001” Note: To confirm linkage with the correct legacy award record: • In Kuali, select Medusa in the “-00001” record. • In the list that appears, select any award record except for the “-00001” Parent (the legacy data does not reside in the “Parent” record). -

Lowara 1300 Series Uk Version Jan2015 REV MAY 2015.Indd

Pure performance LOWARA ® 1300 SERIES - 50HZ Available EASY TO SELECT, CLOSE AT HAND, RIGHT PUMP FOR YOUR NEEDS Value for money EFFICIENT, POWERFUL Reliable SOLIDS HANDLING, CONTINUOUS RUNNING 2 Readily available pure performance pumps Lowara® 1300 is a series of submersible pumps that deliver pure performance at outstanding value. Combining performance and quality in a The Lowara® 1300 series is based on convenient, value for money package, these technology developed and tested in pumps will help ensure the smooth running tough environments the world over. and profi tability of your operation. This is That’s why you can count on these pumps why Lowara is the ideal pump for sewage for trouble-free, reliable operation. and surface wastewater within domestic and commercial building applications. The hydraulic design of the pumps has been proven to reduce clogging Moreover, Lowara makes your choice of and maintain efficiency. These pumps pump easy, it only requires three straight- simply work and keep on working. forward steps. We have the right pump Day in, day out, and under harsh for your needs with high availability to conditions, they won’t let you down – support your business. they’re Lowara® 1300. 3 Available Value for money Reliable With a variety of combinations of non-clog submersible applications. The motors and vortex impellers to choose from, it´s have F-class insulation and can handle 15 easy to fi nd a pump for your needs. The starts per hour. impeller design gives you effi ciency and solids handling capability. This helps to Typically these pumps are installed in ensure smooth operation and delivers permanent installations. -

The Kingship of David II (1329-71)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository 1 The Kingship of David II (1329-71) Although he was an infant, and English sources would jibe that he soiled the coronation altar, David Bruce was the first king of Scots to receive full coronation and anointment. As such, his installation at Scone abbey on 24 November 1331 was another triumph for his father.1 The terms of the 1328 peace had stipulated that Edward III’s regime should help secure from Avignon both the lifting of Robert I’s excommunication and this parity of rite with the monarchies of England and France. David’s coronation must, then, have blended newly-borrowed traditions with established Scottish inaugural forms: it probably merged the introduction of the boy-king and the carrying of orb, sceptre and sword by the incumbents of ancient lines of earls, then unction and the taking of oaths to common law and church followed by a sermon by the new bishop of St Andrews, the recitation of royal genealogy in Gaelic and general homage, fealty and knighting of subjects alongside the king.2 Yet this display must also have been designed to reinforce the territorial claims of authority of the Bruce house in the presence of its allies and in-laws from the north, west and south-west of Scotland as well as the established Lowland political community. Finally, it was in part an impressive riposte to Edward II’s failed attempts to persuade the papacy of his claim for England’s kings to be anointed with the holy oil of Becket.3 1 Chronica Monasterii de Melsa, ed. -

Age of Chivalry

The Constraints Laws on Warfare in the Western World War Edited by Michael Howard, George J. Andreopoulos, and Mark R. Shulman Yale University Press New Haven and London Robert C . Stacey 3 The Age of Chivalry To those who lived during them, of course, the Middle Ages, as such, did not exist. If they lived in the middleof anything, most medieval people saw themselves as living between the Incarnation of God in Jesus and the end of time when He would come again; theirown age was thus a continuation of the era that began in the reign of Caesar Augustus with his decree that all the world should be taxed. The Age of Chivalry, however, some men of the time- mostly knights, the chevaliers, from whose name we derive the English word "chivalry"-would have recognized as an appropriate label for the years between roughly I 100 and 1500.Even the Age of Chivalry, however, began in Rome. In the chansons de geste and vernacular histories of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Hector, Alexander, Scipio, and Julius Caesar appear as the quintessential exemplars of ideal knighthood, while the late fourth or mid-fifth century Roman military writer Vcgetius remained far and away the most important single authority on the strategy and tactics of battle, his book On Military Matters (De re military passing in transla- tion as The Book of Chivalry from the thirteenth century on. The Middle Ages, then, began with Rome; and so must we if we are to study the laws of war as these developed during the Age of Chivalry. -

STUDIES of the VENERABLE BEDE, the GREAT FAMINE of 1315-1322, and LIBRARIES in PRISONER of WAR CAMPS a Paper Submitted to the Gr

STUDIES OF THE VENERABLE BEDE, THE GREAT FAMINE OF 1315-1322, AND LIBRARIES IN PRISONER OF WAR CAMPS A Paper Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Trista Stephanie Raezer-Stursa In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Department: History, Philosophy, and Religious Studies October 2017 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title STUDIES OF THE VENERABLE BEDE, THE GREAT FAMINE OF 1315-1322, AND LIBRARIES IN PRISONER OF WAR CAMPS By Trista Stephanie Raezer-Stursa The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Dr. Gerritdina (Ineke) Justitz Chair Dr. Verena Theile Dr. Mark Harvey Approved: October 19, 2017 Dr. Mark Harvey Date Department Chair ABSTRACT This paper includes three studies about the Venerable Bede, the Great Famine of 1315- 1322, and libraries in prisoner of war camps. The study of the Venerable Bede focuses on his views on and understanding of time, especially its relation to the Easter computus. The second study is a historiography of the Great Famine of 1315-1322, with an emphasis on the environmental aspects of the catastrophe. The third paper is a study of the libraries that were provided for German soldiers in prisoner of war camps in the United States during World War II, which includes an analysis of the role of reading in the United States’ attempt to re-educate the German prisoners.