The Gaddi Shepherds of Himachal Himalayas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kangra, Himachal Pradesh

` SURVEY DOCUMENT STUDY ON THE DRAINAGE SYSTEM, MINERAL POTENTIAL AND FEASIBILITY OF MINING IN RIVER/ STREAM BEDS OF DISTRICT KANGRA, HIMACHAL PRADESH. Prepared By: Atul Kumar Sharma. Asstt. Geologist. Geological Wing” Directorate of Industries Udyog Bhawan, Bemloe, Shimla. “ STUDY ON THE DRAINAGE SYSTEM, MINERAL POTENTIAL AND FEASIBILITY OF MINING IN RIVER/ STREAM BEDS OF DISTRICT KANGRA, HIMACHAL PRADESH. 1) INTRODUCTION: In pursuance of point 9.2 (Strategy 2) of “River/Stream Bed Mining Policy Guidelines for the State of Himachal Pradesh, 2004” was framed and notiofied vide notification No.- Ind-II (E)2-1/2001 dated 28.2.2004 and subsequently new mineral policy 2013 has been framed. Now the Minstry of Environemnt, Forest and Climate Change, Govt. of India vide notifications dated 15.1.2016, caluse 7(iii) pertains to preparation of Distt Survey report for sand mining or riverbed mining and mining of other minor minerals for regulation and control of mining operation, a survey document of existing River/Stream bed mining in each district is to be undertaken. In the said policy guidelines, it was provided that District level river/stream bed mining action plan shall be based on a survey document of the existing river/stream bed mining in each district and also to assess its direct and indirect benefits and identification of the potential threats to the individual rivers/streams in the State. This survey shall contain:- a) District wise detail of Rivers/Streams/Khallas; and b) District wise details of existing mining leases/ contracts in river/stream/khalla beds Based on this survey, the action plan shall divide the rivers/stream of the State into the following two categories;- a) Rivers/ Streams or the River/Stream sections selected for extraction of minor minerals b) Rivers/ Streams or the River/Stream sections prohibited for extraction of minor minerals. -

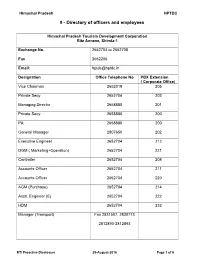

9 - Directory of Officers and Employees

Himachal Pradesh HPTDC 9 - Directory of officers and employees Himachal Pradesh Tourism Development Corporation Ritz Annexe, Shimla-1 Exchange No. 2652704 to 2652708 Fax 2652206 Email: [email protected] Designation Office Telephone No PBX Extension ( Corporate Office) Vice Chairman 2652019 205 Private Secy 2652704 203 Managing Director 2658880 201 Private Secy 2658880 200 PA 2658880 200 General Manager 2807650 202 Executive Engineer 2652704 212 DGM ( Marketing+Operation) 2652704 221 Controller 2652704 208 Accounts Officer 2652704 211 Accounts Officer 2652704 220 AGM (Purchase) 2652704 214 Asstt. Engineer (E) 2652704 222 HDM 2652704 232 Manager (Transport) Fax 2831507, 2830713 2812890-2812893 RTI Proactive Disclosure 29-August-2016 Page 1 of 6 Himachal Pradesh HPTDC Designation Office Telephone No HOLIDAY HOME COMPLEX Dy GM 2656035 Sr.Manager (Peterhof) 2812236 Fax-2813801 Asstt. Mgr. Apple C.InnKiarighat 01792-208148 Incharge, Hotel Bhagal 01796-248116, 248117 Asstt. Mgr. Golf Glade, Naldehra 2747809, 2747739 Incharge, HtlMamleshwar, Chindi 01907- 222638 Sr. Manager, Apple Blossom, Fagu 01783-239469 Incharge. Lift (HPTDC) 2807609 CHAMBA-DALHOUSIE COMPLEX Sr. Manager, Marketing Office 1899242136 Sr.Manager,HotelIravati 01899-222671 Incharge, Hotel Deodar, Khajjiar 01899-236333 Incharge, Hotel Geetanjli, Dalhousie 01899-242155 The Manimahesh, Dalhousie 01899-242793, 242736 DHARAMSHALA COMPLEX AGM, Mkt. Office 01892-224928, 224212 AGM, Dhauladhar 01892-224926, 223456 Asstt. Manager, Kashmir House 01892-222977 Sr.Manager, Hotel Bhagsu 01892-221091 Asstt. Manager, Hotel Kunal 01892-223163, 222460 Designation Office Telephone No RTI Proactive Disclosure 29-August-2016 Page 2 of 6 Himachal Pradesh HPTDC Asstt. Manager,Club House 01892-220834 Asstt. Manager, Yatri Niwas, Chamunda 01892-236065 Incharge, The Chintpurni Height 01976-255234 JAWALAJI COMPLEX Asstt. -

Contributions to the Geology of the North-Western Himalayas 1-59 ©Geol

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Abhandlungen der Geologischen Bundesanstalt in Wien Jahr/Year: 1975 Band/Volume: 32 Autor(en)/Author(s): Fuchs Gerhard Artikel/Article: Contributions to the Geology of the North-Western Himalayas 1-59 ©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at ABHANDLUNGEN DER GEOLOGISCHEN BUNDESANSTALT Contributions to the Geology of the North-Western Himalayas GERHARD FUCHS 64 Figures and 5 Plates BAND 32 • WIEN 1975 EIGENTÜMER, HERAUSGEBER UND VERLEGER: GEOLOGISCHE BUNDESANSTALT, WIEN SCHRIFTLEITUNG: G.WOLETZ DRUCK: BRÜDER HOLLINEK, WIENER NEUDORF ©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at ©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at 3 Abh. Geol. B.-A. Band 32 59 Seiten 64 Fig., 5 Beilagen Wien, Feber 1975 Contribution to the Geology of the North-Western Himalayas By GERHARD FUCHS With 64 figures and 5 plates (= Beilage 1—5) Data up to 1972, except PI. 1 'I NW-Himalaya U Stratigraphie i3 Tektonik £ Fazies Contents Zusammenfassung 3 1.3.1. The Hazara Slates 40 Abstract 4 1.3.2. The Tanol Formation 40 Preface 5 1.3.3. The Sequence Tanakki Boulder Bed — Introduction 5 Sirban Formation 41 1. Descriptive Part 6 1.3.4. The Galdanian and Hazira Formations 42 1.1. Kashmir 6 1.3.5. The Meso-Cenozoic Sequence 44 1.1.1. The Riasi-Gulabgarh Pass Section 6 1.4. Swabi — Nowshera 46 1.1.2. The Apharwat Area . 11 1.4.1. Swabi 46 1.1.3. The Kolahoi-Basmai Anticline (Liddar valley) ... 17 1.4.2. -

Master Thesis “Along Strike Variation of Active Fault Arrays and Their Effect

Master Thesis “Along strike variation of active fault arrays and their effect on landscape morphology in the northwestern Himalaya” Author: Markus Nennewitz 1. Examiner: Dr. Rasmus C. Thiede Mat-Nr.: 754570 2. Examiner: Prof. Dr. Bodo Bookhagen Declaration of plagiarism I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my own independent work, and that in all cases material from the work of others (in books, articles, essays, dissertations, and on the internet) is acknowledged, and quotations and paraphrases are clearly indicated. No other material than that listed has been used. 1/62 Acknowledgements First of all I would like to thank my supervisors Dr. Rasmus Thiede and Prof. Dr. Bodo Bookhagen, who broadend my mind for active tectonics and geomorphology during many meetings and even more e-mail conversations. They supported me in every minute of my work and were always open for questions from my side. Furthermore, I thank them and the DAAD for giving me the opportunity to go on a field trip in NW India. According to that, I would like to mention that I really appreciated the stay at the IIT Gandhinagar for which I also thank Prof. Dr. Vikrant Jain and his Phd-students. Furthermore, I have to thank Saptarshi Dey and Patricia Eugster for providing data files necessary for my analysis. And last but definitely not least I thank my girlfriend and my parents for their tremendous amount of support and for being patient with me during my ongoing work. 2/62 Abstract The location and magnitude of the active deformation of the Himalaya has been in the interest for many decades. -

Baseline Study on Water Supply, Sanitation and Solid Waste in Upper Dharamsala, India

SANDEC Report 09/03 Baseline Study on Water Supply, Sanitation and Solid Waste in Upper Dharamsala, India Bettina Sterkele and Chris Zurbrügg, February 2003 Cover picture: Main road and commercial area of Upper Dharamsala McLeod Ganj, September 2002 (photo Gabriela Friedl) Bettina Sterkele Chris Zurbrugg [email protected] [email protected] Department of Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries (SANDEC) Swiss Federal Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (EAWAG) P.O.Box 611, 8600 Duebendorf, Switzerland www.sandec.ch Table of Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................8 2 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................10 3 Study Methodology ........................................................................................................................12 3.1 Preparation............................................................................................................................12 3.2 Field work..............................................................................................................................15 3.2.1 Observation...........................................................................................................................15 3.2.2 Interviews with key persons ..................................................................................................15 -

49108-002: Himachal Pradesh Skills Development Project

Initial Environment Examintaion Project Number: 49108-002 October 2019 IND: Himachal Pradesh Skills Development Project Package : Rural Livelihood Center at Bijahi, Thunag Tehsil, Mandi District Submitted by : Government of Himachal Pradesh This initial environment examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 49108-002 September 2019 India: Himachal Pradesh Skill Development Project Sub-project– Rural Livelihood Center at Bijahi, Thunag Tehsil, Mandi District Prepared by the Government of Himachal Pradesh for the Asian Development Bank This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Page 1 of 86

Page 1 of 86 Page 1 of 86 Page 1 of 86 Page 1 of 86 Page 1 of 86 Page 1 of 86 Page 1 of 86 Page 1 of 86 Page 1 of 86 AUTO YEAR IVPR_SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN REG_NUM QUALIF MOBILE EMAIL 3931 1994 4194 417 01.10.42 BHYAN GIASUDDIN C/O GUPTA COTTAGE LOWER ROAD HIMACHAL 171003 ASM/0071/84 BVSc & AH/67/Guwahati SHIMLA 171003 HIMACHAL PRADESH Uni PRADESH 134 1994 141 266 KHAGENDRA NATH GOWAL CENTRAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE HIMACHAL 173204 ASM/0084/84 BVSc & AH/69/AAU KASAULI 173204 HIMACHAL PRADESH PRADESH 278 1994 297 273 MISRA JYOTISH CHANDRA H.NO 251/6,LOWER SAMKHATER HIMACHAL 171001 ASM/0338/84 BVSc & AH/70/AAU MANDOS DISST MANDI(H.P) 171001 PRADESH HIMACHAL PRADESH 787 1994 841 294 LAXMI DHAR SHARMA VIL CHHOTI HALER JOGIPUR ROAD HIMACHAL ASM/0946/90 BVSc&AH/90/AAU KANGRA HIMACHAL PRADESH PRADESH 3291 1994 3533 391 01.01.68 MD SHAHZAHAN ALI KANWAR NIWAS NIEAM VIHAR HIMACHAL 171002 ASM/1068/91 BVSc & AH/91/AAU SHIMLA 2 SHIMLA 171002 PRADESH HIMACHAL PRADESH 1156 1994 1238 307 SWADESH CHANDER KAPIL VETERINARY OFFICER VETERINARY HIMACHAL 174030 DVC/72/91 BVSc & AH/61/Punj Un HOSPITAL-DASHLEHRA BILASPUR PRADESH 174030 HIMACHAL PRADESH 932 1994 994 299 24/07/55 KAPOOR PAWAN KUMAR I/C SUB DIV VETY HOSPITAL SUNDER HIMACHAL HEC/205/ 86 BVSc & AH/Un Ud/80 9418278699 [email protected] S/O SH JL KAPUR NAGAR MANDI HIMACHAL PRADESH PRADESH m 812 1994 867 295 07/03/53 YUVRAJ MOHAN AZAD S/O V & PO DALASH KULLU HP HIMACHAL HEC/23/86 BVSc&AH/HAU/80 SH JR PRAKASH HIMACHAL PRADESH PRADESH 919 1994 980 299 18/10/52 TARACHAND CHAUHAN VETERINARY HOSPITAL RAMPUR HIMACHAL HP184/86 B.V.SC & A.H. -

The Dhauladhar Range in the Northwestern Himalaya

RESEARCH Sustained out-of-sequence shortening along a tectonically active segment of the Main Boundary thrust: The Dhauladhar Range in the northwestern Himalaya Rasmus Thiede1, Xavier Robert2, Konstanze Stübner3, Saptarshi Dey1, and Johannes Faruhn1 1INSTITUT FÜR ERD- UND UMWELTWISSENSCHAFTEN, UNIVERSITÄT POTSDAM, KARL-LIEBKNECHT-STRASSE 25, HAUS- 27, POTSDAM-14476, GERMANY 2UNIVERSITÉ GRENOBLE ALPES, CNRS (CENTRE NATIONAL DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE), IRD (INSTITUT DE RECHERCHE POUR LE DÉVELOPPEMENT), ISTERRE (INSTITUT DES SCIENCES DE LA TERRE), F38000 GRENOBLE, FRANCE 3INSTITUT FÜR GEOWISSENSCHAFTEN, EBERHARD KARLS UNIVERSITÄT TÜBINGEN, TÜBINGEN, GERMANY ABSTRACT Competing hypotheses suggest that Himalayan topography is sustained and the plate convergence is accommodated either solely along the basal décollement, the Main Himalayan thrust (MHT), or more broadly, across multiple thrust faults. In the past, structural, geomorphic, and geodetic data of the Nepalese Himalaya have been used to constrain the geometry of the MHT and its shallow frontal thrust fault, known as Main Frontal thrust (MFT). The MHT flattens at depth and connects to a hinterland mid-crustal, steeper thrust ramp, located ~100 km north of the deformation front. There, the present-day convergence across the Himalaya is mostly accommodated by slip along the MFT. Despite a general agreement that in Nepal most of the shortening is accommodated along the MHT, some researchers have suggested the occurrence of persistent out-of-sequence shortening on interior faults near the Main Central thrust (MCT). Along the northwest Himalaya, in contrast, some of these characteristics of central Nepal are missing, suggesting along-strike variation of wedge deformation and MHT fault geometry. Here we present new field observations and seven zircon (U-Th)/He (ZHe) cooling ages combined with existing low-temperature data sets. -

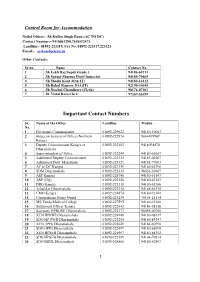

Important Contact Numbers

Control Room for Accommodation Nodal Officer:- Sh Kulbir Singh Rana (AC TO DC) Contact Number:- 9418061290,7018512473 Landline:- 01892-223319, Fax No. 01892-223317,223323 Email:- [email protected] Other Contacts: Sr no. Name Contact No. 1 Sh Lekh Raj Supdt Grade 1 94184-64711 2 Sh Sanjay Sharma Hotel Inspector 94180-79465 4 Sh Shashi Kant JOA(IT) 94183-13412 5 Sh Rahul Kapoor JOA(IT) 82190-34045 6 Sh Nischal Chaudhary (Clerk) 98176-07101 7. Sh. Vishal Rana Clerk 97367-36359 Important Contact Numbers Sr Name of the Office Landline Moblie No. 1 Divisional Commissioner 01892-229022 94180-50003 2 Inspector General of Police (Northern 01892-222570 9664499909 Range) 3 Deputy Commissioner Kangra at 01892-222103 9418094470 Dharamshala 4 Superintendent of Police 01892-222244 94180-03007 5 Additional Deputy Commissioner 01892-223322 94183-00567 6 Additional Distt. Magistrate 01892-223321 94181-77083 7 AC to DC Kangra 01892-223319 94180-61290 8 SDM Dharamshala 01892-223315 98053-30007 9 ASP Kangra 01892-228746 94180-51147 10 ASP (HQ) 01892-222150 94180-63143 11 DRO Kangra 01892-223318 94180-65366 12 Tehsildar Dharamshala 01892-223314 94185-56178 13 CMO Kangra 01892-224874 94180-93360 14 Commandant Home Guard 01892-223234 70181-21114 15 MS Tanda Medical College 01892-227595 94180-93360 16 Settlement Officer Kangra 01892-222443 94184-58158 17 Secretary HPBOSE Dharamshala 01892-222373 98055-00700 18 XEN HPPWD Dharamshala 01892-224946 94180-08137 19 SDO HP PWD Dharamshala 01892-223254 94180-89247 20 XEN (IPH) Dharamshala 01892-222049 94184-60398 21 SDO (IPH) Dharamshala 01892-222499 94180-65090 22 XEN HPSEB Dharamshala 01892-224997 94180-88352 23 SDO HPSEB Dharamshala 01892-222169 94184-76814 24 SDO BSNL Dharamshala 01892-228868 94180-53893 1 2 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY VIDHAN SABHA 2018 Sr. -

Prospects of Tourism and Its Infrastructural Gaps in Dhauladhar Circuit Dr

IJA MH International Journal on Arts, Management and Humanities 6(2): 193-200(2017) ISSN No. (Online): 2319–5231 Prospects of Tourism and its Infrastructural Gaps in Dhauladhar Circuit Dr. Nitin Vyas* and Surjeet Kumar** *Assistant Professor, Department of Vocational Studies, Himachal Pradesh University, Shimla, (Himachal Pradesh), India **Research Scholar, Department of Vocational Studies, Himachal Pradesh University, Shimla, (Himachal Pradesh), India (Corresponding author: Dr. Nitin Vyas) (Received 19 November, 2017, Accepted 16 December, 2017) (Published by Research Trend, Website: www.researchtrend.net) ABSTRACT: Tourism is one of the fastest growing industries in the hilly state of Himachal Pradesh. The State has immense potential for religious, cultural, adventures, leisure and heritage tourism. The major tourist destinations are Shimla, Kullu, Manali, Dharamshala, McLeod Gang and Dalhousie. People from all over the world attracted with charming beauty of Himalayan ranges. Tourism is the third largest industry after hydropower and agriculture. This paper deals with tourism in Dhauladhar travel circuit. This circuit starts from Dalhousie, Khajjiar, Chamba, Bharmour, Dharamshala, Kangra and Palampur. This paper deals with the prospects of tourism in Dhauladhar circuit and availability of infrastructural facilities to the tourists in this region. It also examines the Tourism Infrastructure Gaps in Dhauladhar Travel Circuit. Keywords: Tourist circuit, heritage Tourism, infrastructural gap. I. INTRODUCTION Tourism is one of the fastest growing industries in the country. In recent time tourism industry one of the important sector contributing to the economy for the future growth of the nation. In the vibrant Socio-Economic and Political situation, international and national government considering travel and tourism as a tool of progress as per data released by United Nation Word Tourism Organization. -

Natural Resources N M a O G M I V CO D ER in N MENT OF

AL P R CH AD A E NT E M PM R S I O E H L P H E O V R E T D Chapter 2 H H P L N A O N I S N S G I I Natural Resources N M A O G M I V CO D ER IN N MENT OF Natural resources provide the base on which the edifice Lesser Himalayas of development is raised. Its use depends upon the type This zone extends to 65 to 85 km with an average of economy, the level of technology and preferences of elevation of about 3300 mts above the mean sea level, the culture of a given society. The importance of and forms the central part of state. The important natural resources is more critical to societies which are ranges here are the Pir Panjal and Dhauladhar Ranges. at a relatively low level of development. People have to The Pir Panjal range form the water divide between conform their livelihood and life style to the settings of Chenab river on the one side and the Ravi and Beas on nature. The sustainable use of natural resources to the other. The Dhauladhar is a majestic snow clad range attain high levels of human development has become cut across by rivers like the Ravi, Beas and Sutluj. Both imperative. Natural resources of Himachal Pradesh have north and south facing slopes support luxuriant forests, a direct relationship with its physiographic conditions except in tracts above the snowline. It is marked by including relief, drainage, climate and geology. -

Beas Valley Power Corp., Balh

DRAFT EIA/EMP REPORT Stone/Sand/Bajri Mine, (With ML Area of 5.1288 Ha) Kh. No. 1212/1 and 1215/1, Balh, Patwar Circle Balh, Joginder Nagar, Mandi, Himachal Pradesh JULY 2013 Submitted by: M/s Beas Valley Power Corporation Limited Joginder Nagar, District-Mandi, Himachal Pradesh EIA Consultant: EQMS INDIA PVT. LTD. INDIA 304-305, 3rd Floor, Plot No. 16, Rishabh Corporate Tower, Community Centre, Karkardooma, Delhi – 110092 Phone: 011-30003200, 30003219; Fax: 011-22374775 Website: www.eqmsindia.com ; E-mail – [email protected] Draft EIA/EMP report of Stone/Sand/Bajri Mine, (With ML Area of 5.1288 Ha) Kh. No. 1212/1 and 1215/1, Balh, Patwar Circle Balh, Joginder Nagar, Mandi, Himachal Pradesh Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 1.1. Preamble ............................................................................................................................ 6 1.2. Purpose of the Report ........................................................................................................ 6 1.3. Identification of Project & Project Proponent ....................................................................... 7 1.4. Brief description of nature, size and location of the project ................................................. 7 1.5. Salient Features of the Project ......................................................................................... 12 1.6. Need for the project and its importance to the