Continuing to Treat Workers Like Widgets and Digits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Workplaces Review Final Report May 23, 2017

Changing Workplaces Review Final Report May 23, 2017 Dear Clients and Friends, Today, the Government of Ontario released the Changing Workplaces Review final report and recommendations, labeling it an “An Agenda for Workplace Rights”. Touted as the first independent review of the Employment Standards Act and Labour Relations Act in more than a generation, the review was commenced in February, 2015. For every Ontario employer, the recommended changes to the Employment Standards Act and Labour Relations Act are far reaching and will have significant impact. The government has undertaken to announce its formal response to the report in the coming days, and may be aiming to table draft legislation modeled on all, or part, of the recommendations prior to the Legislature rising for summer recess (June 1, 2017). If that occurs we could see legislation make its way into force by late Fall or early next year. Sherrard Kuzz LLP will review the report and government response and distribute a comprehensive briefing note, as we did following the release of the Interim Report (see Sherrard Kuzz LLP homepage). In the interim, to review the report click here, and the summary report click here. Sherrard Kuzz LLP is one of Canada’s leading employment and labour law firms, representing management. Firm members can be reached at 416.603.0700 (Main), 416.420.0738 (24 Hour) or by visiting www.sherrardkuzz.com. MAY 2017 THE CHANGING WORKPLACES REVIEW AN AGENDA FOR WORKPLACE RIGHTS Summary Report SPECIAL ADVISORS C. MICHAEL MITCHELL JOHN C. MURRAY TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHANGING WORKPLACES RECOMMENDATIONS ON Related and Joint Employer ..............................50 REVIEW: AN AGENDA FOR LABOUR RELATIONS ...................................... -

Temporary Employment in Stanford and Silicon Valley

Temporary Employment in Stanford and Silicon Valley Working Partnerships USA Service Employees International Union Local 715 June 2003 Table of Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………….1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..5 Temporary Employment in Silicon Valley: Costs and Benefits…………………………………..8 Profile of the Silicon Valley Temporary Industry.………………………………………..8 Benefits of Temporary Employment…………………………………………………….10 Costs of Temporary Employment………………………………………………………..11 The Future of Temporary Workers in Silicon Valley …………………………………...16 Findings of Stanford Temporary Worker Survey ……………………………………………….17 Survey Methodology……………………………………………………………………..17 Survey Results…………………………………………………………………………...18 Survey Analysis: Implications for Stanford and Silicon Valley…………………………………25 Who are the Temporary Workers?……………………………………………………….25 Is Temp Work Really Temporary?………………………………………………………26 How Children and Families are Affected………………………………………………..27 The Cost to the Public Sector…………………………………………………………….29 Solutions and Best Practices for Ending Abuse…………………………………………………32 Conclusion and Recommendations………………………………………………………………38 Appendix A: Statement of Principles List of Figures and Tables Table 1.1: Largest Temporary Placement Agencies in Silicon Valley (2001)………………….8 Table 1.2: Growth of Temporary Employment in Santa Clara County, 1984-2000……………9 Table 1.3: Top 20 Occupations Within the Personnel Supply Services Industry, Santa Clara County, 1999……………………………………………………………………………………10 Table 1.4: Median Usual Weekly Earnings -

Information About Unemployment Insurance for Workers on Temporary Layoff

Information about Unemployment Insurance for Workers on Temporary Layoff What is a Temporary Layoff? A temporary layoff occurs when you are partially unemployed because of lack of work or you have worked less than the equivalent of 3 customary, scheduled, full-time days for your plant or industry and earn less than your ineligible amount (earnings allowance plus your weekly benefit amount).Your employer will notify you when a temporary layoff occurs or is pending, and will prepare the information needed to file for temporary unemployment insurance benefits. Your employer is allowed to file a temporary layoff claim only once during your benefit year and this one occurrence is limited to a maximum of 6 consecutive weeks. The first week of this series is a waiting period week for which no benefits can be paid. After this six week period has passed (if you are still unemployed) you will need to file your own claim for unemployment benefits. What Happens Next? After your new claim is filed, you will be mailed Form N CUI-550, Wage Transcript and Monetary Determination. This form shows the employer(s) for whom you worked during the base period applicable to your claim, and the amount of wages they paid you during each quarter. It also shows the weekly amount of benefits payable to you and the number of weeks for which benefits may be paid during your benefit year. Currently, the maximum weekly benefit amount payable is $350 per week. The number of weeks payable at the full weekly benefit amount varies based on the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate. -

Employment Downsizing and Its Alternatives

SHRM Foundation’s Effective Practice Guidelines Series Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives STRATEGIES FOR LONG-TERM SUCCESS Sponsored by Right Management SHRM FOUNDAtion’S EFFECTIVE PraCTICE GUIDELINES SERIES Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives STRATEGIES FOR LONG-TERM SUCCESS Wayne F. Cascio Sponsored by Right Management Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the subject matter covered. Neither the publisher nor the author is engaged in rendering legal or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent, licensed professional should be sought. Any federal and state laws discussed in this book are subject to frequent revision and interpretation by amendments or judicial revisions that may significantly affect employer or employee rights and obligations. Readers are encouraged to seek legal counsel regarding specific policies and practices in their organizations. This book is published by the SHRM Foundation, an affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM©). The interpretations, conclusions and recommendations in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the SHRM Foundation. ©2009 SHRM Foundation. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the SHRM Foundation, 1800 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA 22314. The SHRM Foundation is the 501(c)3 nonprofit affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). -

Notice of Layoff Or Reassignment

Attachment B DHRM Form L-1 First Notice Rev. 10/07 Commonwealth of Virginia Final Notice Notice of Layoff or Placement This section is to be completed by the agency human resource officer Agency Name Date Employee Employee ID Name Number Position Role SOC Code Number Pay Current Semi-Monthly Band Salary Effective , you are being placed in the following position: Role SOC Code Position Number Location Semi-Monthly Salary are being placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months because there is no placement opportunity available to you under the State Layoff Policy. If you are being placed, options available to you are marked with an X below. You may decline the placement if it requires relocating your residence, and proceed to the next placement opportunity available to you under the Layoff Policy, if any other options are available. If none are available, I will be placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months. You may decline the placement since it is to a position that will result in a salary decrease, and request that you be placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months. If you do not accept the placement, your only option is to be separated-layoff because it will not result in salary decrease or need to relocate. You will not be entitled to severance benefits. Signed Title This section is to be filled in by the employee and returned to the human resource officer no later than . If you do not return the form by this date, agency management will determine your placement. -

Temporary H Ou Rly Employees at Th E C Ity of P Alo a Lto Policy Brief O Ctober 2004

Temporary H ou rly Employees at th e C ity of P alo A lto Policy Brief O ctober 2004 In 1994, follow ing a comprehensive on temps each year, w hile red!cing permanent organizational review commissioned by the C ity positions$ any of today#s ho!rlies have been of Palo Alto, the C ity anager fo!nd one of the w or2ing for the C ity since before the 1994 st!dy ma"or problems in the C ity#s organization to be came o!t 3 ten, fifteen, even tw enty years as a the over!se and mis!se of temporary ho!rly %temporary) w or2er, doing the same w or2 as employees$ %A n!mber of &temporary ho!rly' permanent employees b!t w ith no health positions have contin!ed on a year-to-year benefits, no time off and no "ob sec!rity$ And basis, and need to be made permanent for the ,ebr!ary -..4 C ity A!ditor#s 4eport once reasons of efficiency and e(!ity,) she concl!ded$ again recommends that %* !man 4eso!rces %* o!rly positions w hich are performing the sho!ld clarify C ity policies regarding the same d!ties as reg!lar positions and remain in appropriate !ses of ho!rly employees, and the b!dget year after year, can not be view ed as establish standard definitions and practices for +temporary# and therefore are recommended for hiring and monitoring temporary employees$) conversion$) A decade later, the C ity has made little if any progress in fi5ing its system of temporary ,ast-forw ard to -..4$ /he C ity employs over employment$ 01. -

The Essential Guide to Handling a Layoff Table of Contents

Tools, tips, and templates to ensure a smooth transition The Essential Guide to Handling a Layoff Table of Contents Section One: How to Select Who to Layoff 05 Employee Layoff Selection Guide Multi–Criteria Layoff Selection Guide Section Two: Worker Adjustment & Retraining Notification 14 Checklist Sample Letter Section Three: How to Layoff an Employee 18 Reduction Checklist Layoff Script Layoff Letter / Layoff Memo / Layoff Form Severance Pay Policy / Severance Calculator Offboarding Checklist Exit Interview Questionnaire How to handle a layoff with confidence and care Careful planning and preparation are key to successfully managing a layoff. But too often, the day-to-day demands of a busy workplace leave little opportunity to put in place the information and materials that allow an employer to ease — for everyone involved — the turmoil a layoff can bring. That’s why this ebook has been created. Making the hard choices For managers and HR professionals, having to let people go is one of the most difficult parts of the job, even when it’s clear that it’s a necessary step. And for employees directly impacted by that decision, a layoff is not only difficult, but it can also initially be devastating, especially when loyal and productive employees have to be let go due to a company’s decision to downsize in order to remain viable. A reduction in force is also likely to affect the morale of the employees who remain on the job. As tough as layoffs can be, it is possible to do them in ways that make things easier on everyone — ways that illustrate for laid-off employees the fact that the company cares about them as people; ways that also leave remaining employees feeling reassured by the way a layoff has been handled. -

Steps to Successful Implementation of Worker-To

INTRODUCTION This handbook is provided to help UAW local unions plan and implement a Member to Member program. While we strongly recommend that those responsible for the success of their local union Member to Member program attend an in-person training, this handbook is designed to allow a local union to start their own program with confidence. The UAW’s Member to Member program has been a big part of our internal organizing strategy for many years. Its goal is to strengthen our union through strong member relationships and communication supported by a dedicated local union activist network system. When Member to Member is done right, we get more members engaged to help us succeed in our representational, political, and community work. This not only benefits us; it also benefits our family and friends, and supports our bigger goal of building power to win social, economic, and political justice for all. We know one-on-one conversations inspire unorganized workers to organize through sharing stories and understanding that worker solidarity solves work problems better than struggling alone. That tested organizing technique works well with current members too. Along with personal interactions, Member to Member uses social media to help us “walk the talk” that our members “are the union.” HOW DOES THE MEMBER TO MEMBER PROGRAM WORK? The Member to Member program uses Worksite Coordinators, Organizers and Communicators to create, build and sustain a communication and relationship-building network in each local union- represented worksite. A specific training is available for each union member playing a role in this program. -

Temp Work at an All Time High

National Employment Law Project National Employment Law Project For Immediate Release: September 2, 2014 Contact: Emma Stieglitz, [email protected], (646) 200-5307 Temp Work At An All Time High Rise of Temp Work, Staffing Agencies Ushers in Lower Wages, Dangerous Conditions for Workers, Report Says There are a record high 2.8 million temporary help jobs in today’s economy, making up 2 percent of total employment, according to a report released Tuesday by the National Employment Law Project. The report, Temped Out: How The Domestic Outsourcing of Blue-Collar Jobs Harms America’s Workers, examines the employment services industry, which includes temporary help agencies (also called staffing agencies), professional employer organizations and employment placement agencies. It finds that as a whole, the industry represents 2.5 percent of all jobs, up from 1.4 percent in 1990. More than 12 million people flowed into and out of a staffing agency in 2013 alone. America’s staffing industry has also shifted its reach to new sectors like manufacturing and warehousing. The use of third-party staffing agencies creates a layered employment structure that empowers the client-employers at the top and puts downward pressure on staffing agencies in the middle competing for contracts. Many of those agencies in turn keep costs low by cutting corners on pay and safety for workers. In fact, staffing workers' median hourly wages are 22 percent lower than wages of all private-sector workers. “The shift towards temp work is creating an economy in which working people who move and produce products for some of our nation’s largest and most profitable corporations are treated like any other input, to be acquired at the cheapest cost,” said Rebecca Smith, who co-authored the report. -

57 ARTICLE 26: LAYOFF A. General Provisions the Employer Shall

ARTICLE 26: LAYOFF A. General Provisions The Employer shall determine when temporary or indefinite layoffs are necessary. B. Definitions 1. Temporary layoff affecting a career position is for a specified period of less than four (4) calendar months from the date of layoff. 2. Indefinite layoff affecting a career position is one which is four (4) or more calendar months. C. Temporary Layoff 1. An employee shall be given written notice of the effective date and the ending date of a temporary layoff. The notice shall be given at least thirty (30) calendar days prior to the effective date. D. Indefinite Layoff 1. The order of layoff for indefinite career employees in the same classification (defined as the four (4) digits of the title code) within a unit defined by the Employer is in inverse order of seniority except that the department head may retain employees irrespective of seniority who possess special skills, knowledge, or abilities that are not possessed by other employees in the same classification with greater seniority, and that are necessary to perform the ongoing function of the department. 2. Seniority: Seniority shall be calculated by the number of career full-time equivalent months (or hours) of LLNL service. Employment prior to a break in service shall not be counted. When employees have the same number of full-time equivalent months (or hours), the employee with the most recent date of appointment shall be deemed the least senior. 3. Notice: An employee will receive at least thirty (30) calendar days written notice prior to indefinite layoff. If less than thirty (30) calendar days notice is provided, the employee shall receive straight-time pay in lieu of notice for each additional day the employee would have been on pay status had the employee been given thirty (30) calendar days notice. -

Reemploying Displaced Adults

Technology and Structural Unemployment: Reemploying Displaced Adults February 1986 NTIS order #PB86-206174 'iffii©1Jl0il@~@®11 ';:'Oil", >:;1iWl!!l©1(:Woo&~ l!!l Oil 1liil£1m@111l11li1m1i', REEMPLOYING DISPLACED ADULTS 'iil'-.-- ~:::.::::':::" - Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Technology and Structural Unem- ployment: Reemploying Displaced Adults, OTA-ITE-250 (Washington, DC: U.S. Gov- ernment Printing Office, February 1986). Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 85-600631 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 Foreword The problems of displaced adults have received increasing attention in the 1980s, as social, technological, and economic changes have changed the lifestyles of mil- lions of Americans. Displaced adults are workers who have lost jobs through no fault of their own, or homemakers who have lost their major source of financial support. In October 1983 OTA was asked by the Senate Committee on Finance and the Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources to assess the reasons and out- look for adult displacement, to evaluate the performance of existing programs to serve displaced adults, and to identify options to improve service. In June 1984, the House Committee on Small Business asked OTA to include in the study an ex- amination of trends in international trade and their effects on worker displacement. Worker displacement will continue to be an important issue for the remainder of the decade and beyond, as the U.S. economy adapts to rapid changes in inter- national competition, trade, and technology. While increasing automation and other industry adjustments to new competitive forces benefit the Nation as a whole, they do mean that millions of workers are displaced. -

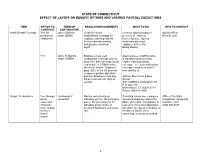

Effect of Layoff on Benefit Options and Various Payroll Deductions April 2016

STATE OF CONNECTICUT EFFECT OF LAYOFF ON BENEFIT OPTIONS AND VARIOUS PAYROLL DEDUCTIONS ITEM OPTION TO TERM OF REGULATIONS/COMMENTS WHAT TO DO WHO TO CONTACT CONTINUE CONTINUATION Health/Dental Coverage Yes, for Up to 4 Months Continue current Continue paying employee Agency HR or permanent under SEBAC health/dental coverage for p r e m i u m share to Benefits Unit employees employee and dependents former Agency. Agency for four calendar months, must manually enroll including the month of employee in Benefits layoff. Billing Module. Yes Up to 30 Months Employee must elect Agency issues COBRA notice under COBRA continuation coverage w/in 60 & enrollment form to each days from date coverage would eligible individual losing end or date of COBRA notice, coverage. To elect continuation whichever is later. Employee coverage complete & submit pays 102% of the full premium form directly to: (employee portion plus state portion). Employee must pay Anthem Blue Cross & Blue full premium w/in 45 days of Shield election. Attn: COBRA Continuation Unit P.O. Box 719 North Haven, CT 06473-0719 Phone: 800-433-5436 Group Life Insurance Yes, through Continuous if May be converted to an If electing conversion, employee Office of the State policy converted individual who le life insurance should immediately contact the Comptroller, Group Life conversion policy. The premiums for the Office of the State Comptroller to Insurance Unit (limited to individual policy will be at request a conversion application. (860) 702-3537 those in plan Dearborn National’s customary (Deadline to request is 30 days of for more rate.