Civil Rights and the Gender Wage Gap in Utah (2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background Checks Benefit Programs Breaks / Meal Periods Bullying in the Workplace

(44169) This publication updates in February/August Essentials of Employment Law Copyright 2018 J. J. Keller & Associates, Inc. 3003 Breezewood Lane P.O. Box 368 Neenah, Wisconsin 54957-0368 Phone: (800) 327-6868 Fax: (800) 727-7516 JJKeller.com Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2015935992 ISBN: 978-1-68008-054-4 Canadian Goods and Services Tax (GST) Number: R123-317687 All rights reserved. Neither the publication nor any part thereof may be reproduced in any manner without written permission of the Publisher. United States laws and Fed- eral regulations published as promulgated are in public domain. However, their compilation and arrangement along with other materials in this publication are subject to the copyright notice. Notwithstanding the above, you may reuse, repurpose, or modify J. J. Keller copy- righted content marked with the “Reuse OK!” icon. This means you may copy all or portions of such content for use within your organization. Use of J. J. Keller content outside of your organization is forbidden. Printed in the U.S.A. ii 2/18 Original content is the copyrighted property of J. J. Keller & Associates, Inc. Essentials of Employment Law Introduction The material in this manual is presented alphabetically by topic. Each topic covers a specific area of compliance or best practices, and includes cross-references to other topics where applicable. The information is provided in a “how to comply” format to provide the most valuable information employers are likely to need. This manual covers over 100 topics, and each tab provides a list of topics covered in that section. Many of the tabs list synonym topics to help you find the material you need. -

Rowansom Student Handbook Regarding the Rowansom Student Code of Conduct and Adhere to the Code of Ethics of the American Osteopathic Association

STUDENT HANDBOOK Go to Table of Contents Stratford, NJ 08084-1501 856-566-6000 https://som.rowan.edu/ August 2021 1 Acknowledgements Preparation of this Student Handbook was made possible through the cooperation of the offices of all divisions of Academic Affairs, Academic Technology, the Dean’s Office, Graduate Medical Education, and Student Financial Aid. The Student Handbook is informational only and does not constitute a contract between Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine and any student. It may be changed by RowanSOM without prior notice to students. Any rules, regulations, policies, procedures or other representations made herein may be interpreted and applied by RowanSOM to promote fairness and academic excellence, based on the circumstances of each individual situation. When modifications of the Student Handbook occur, students will be notified by email. It is each student’s responsibility to check their RowanSOM email on a daily basis and keep abreast of all notifications from RowanSOM. 2 Table of Contents MISSION STATEMENT ................................................................................................................................................. 8 ROWAN UNIVERSITY MISSION ............................................................................................................................................. 8 ROWANSOM MISSION, VISION, ESSENTIAL, VALUES & GUIDING PRINCIPLES ...................................................................... 8 OSTEOPATHIC MEDICINE ........................................................................................................................................... -

Brook Green Supply Limited Modern Slavery Statement - 2020

Brook Green Supply Limited Modern Slavery statement - 2020 This statement is made pursuant to section 54 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015. Brook Green Supply Limited is committed to ensuring that slavery is not present in our business, or supply chain. We have introduced and will continue to develop policy and procedures to ensure that our due diligence to ensure that slavery does not enter the business or supply chain. Our Business We are committed to providing energy supply solutions to Industrial & Commercial consumers across the UK. Aside from supplying 100% REGO-backed power, we are committed to helping customers optimise their energy supply in the context of a grid increasingly characterised by intermittent generation. We have 43 employees, and operate in the United Kingdom, supplying gas and power solely within the UK. Our Approach We have a zero-tolerance approach to slavery and human trafficking. We operate a number of internal policies to ensure that modern slavery and human trafficking is not taking place within our business or supply chain, and that we are conducting business in an ethical and transparent manner. - Our recruitment policy ensures that every member of staff’s eligibility to work in the UK is checked. - Our Anti-bribery and Corruption Policy and Code of Ethics ensure staff are committed to the highest standards and good industry practice. Risk Assessment and Due Diligence We understand modern slavery risks and are committed to ensuring that this is not taking place in our own business or supply chains. We reduce our risk by operating in the UK and provide gas and power solely within the UK. -

Child Protection Program and Policy Should Be Reviewed with Participants Annually

LITTLE LEAGUE® CHILD PROTECTION PROGRAM OVERVIEW The safety and well-being of all participants in the Little League® program is paramount. Little League promotes a player-centric program where young people grow up happy, healthy, and, above all, safe. Little League does not tolerate any type of abuse against a minor, including, but not limited to, sexual, physical, mental, and emotional (as well as any type of bullying, hazing, or harassment). The severity of these types of incidents is life-altering for the child and all who are involved. The goal of the Little League Child Protection Program is to prevent child abuse from occurring through an application screening process for all required volunteers and/or hired workers, ongoing training for its staff and volunteers, increased awareness, and mandatory reporting of any abuse. Little League is committed to enforcing its Child Protection Program, as highlighted below under “Enforcement.” Local Little League programs should establish a zero-tolerance culture that does not allow any type of activity that promotes or allows any form of misconduct or abuse (mental, physical, emotional, or sexual) between players, coaches, parents/guardians/caretakers, spectators, volunteers, and/or any other individual. League officials must remove any individual that is exhibiting any type of mental, physical, emotional, or sexual misconduct and report the individual to the authorities immediately. Little League continues to keep up-to-date with all of its safety policies and procedures within the Child Protection Program, including adherence to the youth protection standards of SafeSport and USA Baseball’s Pure Baseball program. The Child Protection Program provides the resources necessary for a local league Board of Directors to successfully fulfill its requirements. -

M.D. Handbook and Policies

M.D. Handbook and Policies 1 Please note that information contained herein is subject to change during the course of any academic year. Wayne State University School of Medicine (WSUSOM) reserves the right to make changes including, but not limited to, changes in policies, course offerings, and student requirements. This document should not be construed in any way as forming the basis of a contract. The WSUSOM Medicine M.D. Handbook and Policies is typically updated yearly, although periodic mid-year updates may occur when deemed necessary. Unlike degree requirements, changes in regulations, policies and procedures are immediate and supersede those in any prior Medical Student Handbook. The most current version of the WSUSOM of Medicine M.D. Handbook and Policies can always be found on the School of Medicine website. UPDATED 09.15.2021 UNDERGRADUATE MEDICAL EDUCATION MAJOR COMMITTEES • Admissions Committee • Curriculum Committee • Institutional Effectiveness Committee • Professionalism Committee • Promotions Committee 2 DOCUMENT OUTLINE 1. GENERAL STANDARDS 1.1 NEW INSTITUTIONAL DOMAINS OF COMPETENCY AND COMPETENCIES • Domain 1: Knowledge for Practice (KP) • Domain 2: Patient Care (PC) • Domain 3: Practice-Based Learning and Improvement (PBLI) • Domain 4: Interpersonal and Communication Skills (ICS) • Domain 5: Professionalism (P) • Domain 6: Systems-Based Practice (SBP) • Domain 7: Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC) • Domain 8: Personal and Professional Development (PPD) • Domain 13: Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering -

Getting the Record Straight: a Guide to Navigating Background Checks

Getting the Record Straight A Guide to Navigating Background Checks © 2021 John Jay College Institute for Justice and Opportunity John Jay College of Criminal Justice City University of New York, 524 West 59th Street, BMW Suite 609B, New York, NY 10019 The John Jay College Institute for Justice and Opportunity (the Institute), formerly known as the Prisoner Reentry Institute, is a center of research and action at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice/CUNY. The Institute is committed to providing opportunities for people to live successfully in the community after involvement with the criminal legal system. Capitalizing on its position within a large public university and recognizing the transformational power of education, much of its work focuses on increasing access to higher education and career pathways for people with conviction histories. The Institute’s comprehensive and strategic approach includes direct service, research, technical assistance, and policy advocacy. Suggested Citation: The John Jay College Institute for Justice and Opportunity. Getting the Record Straight: A Guide to Navigating Background Checks. New York: The John Jay College Institute for Justice and Opportunity, January 2021. Acknowledgments The John Jay College Institute for Justice and We thank the Policy Team at the Institute for Justice Opportunity would like to thank our College Initiative and Opportunity who created this guide: students who responded to our initial survey, which Alison Wilkey, Director of Public Policy; helped us identify and understand people’s experiences Tommasina Faratro, Special Projects Coordinator; and questions about undergoing background checks. Salik Karim, Advocacy Coordinator; and Zoë Johnson, Policy Coordinator. We are so grateful to the staff, students, and partners who reviewed and provided invaluable feedback We would also like to express our sincere gratitude to on drafts of the guide: Christina Walker, Ellen Piris the Oak Foundation for funding this project. -

Employment Background Checks

Background Checks Tips For Job Applicants and Employees Federal Trade Commission | consumer.ftc.gov Some employers check into your background before deciding whether to hire you or keep you on the job. When they do a background check, you have legal rights under federal law. Depending on where you live, your city or state may offer additional protections. It’s important to know whom to contact if you think an employer has broken the law related to background checks, and an equally good idea to check with someone who knows the laws where you live. Questions About Your Background An employer may ask you for all sorts of information about your background, especially during the hiring process. For example, some employers may ask about your employment history, your education, your criminal record, your financial history, your medical history, or your use of online social media. It’s legal for employers to ask questions about your background or to require a background check — with certain exceptions. They’re not permitted to ask your for medical information until they offer you a job, and they’re not allowed to ask for your genetic information, including your family medical history, except in limited circumstances. When an employer asks about your background, they must treat you the same as anyone else, regardless of your race, national origin, color, sex, religion, 1 disability, genetic information (including family medical history), or age if you’re 40 or older. An employer isn’t allowed to ask for extra background information because you are, say, of a certain race or ethnicity. -

Information About Unemployment Insurance for Workers on Temporary Layoff

Information about Unemployment Insurance for Workers on Temporary Layoff What is a Temporary Layoff? A temporary layoff occurs when you are partially unemployed because of lack of work or you have worked less than the equivalent of 3 customary, scheduled, full-time days for your plant or industry and earn less than your ineligible amount (earnings allowance plus your weekly benefit amount).Your employer will notify you when a temporary layoff occurs or is pending, and will prepare the information needed to file for temporary unemployment insurance benefits. Your employer is allowed to file a temporary layoff claim only once during your benefit year and this one occurrence is limited to a maximum of 6 consecutive weeks. The first week of this series is a waiting period week for which no benefits can be paid. After this six week period has passed (if you are still unemployed) you will need to file your own claim for unemployment benefits. What Happens Next? After your new claim is filed, you will be mailed Form N CUI-550, Wage Transcript and Monetary Determination. This form shows the employer(s) for whom you worked during the base period applicable to your claim, and the amount of wages they paid you during each quarter. It also shows the weekly amount of benefits payable to you and the number of weeks for which benefits may be paid during your benefit year. Currently, the maximum weekly benefit amount payable is $350 per week. The number of weeks payable at the full weekly benefit amount varies based on the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate. -

Employment Downsizing and Its Alternatives

SHRM Foundation’s Effective Practice Guidelines Series Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives STRATEGIES FOR LONG-TERM SUCCESS Sponsored by Right Management SHRM FOUNDAtion’S EFFECTIVE PraCTICE GUIDELINES SERIES Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives STRATEGIES FOR LONG-TERM SUCCESS Wayne F. Cascio Sponsored by Right Management Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the subject matter covered. Neither the publisher nor the author is engaged in rendering legal or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent, licensed professional should be sought. Any federal and state laws discussed in this book are subject to frequent revision and interpretation by amendments or judicial revisions that may significantly affect employer or employee rights and obligations. Readers are encouraged to seek legal counsel regarding specific policies and practices in their organizations. This book is published by the SHRM Foundation, an affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM©). The interpretations, conclusions and recommendations in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the SHRM Foundation. ©2009 SHRM Foundation. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the SHRM Foundation, 1800 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA 22314. The SHRM Foundation is the 501(c)3 nonprofit affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). -

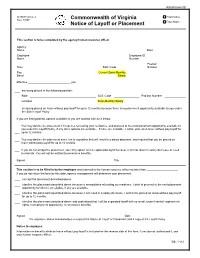

Notice of Layoff Or Reassignment

Attachment B DHRM Form L-1 First Notice Rev. 10/07 Commonwealth of Virginia Final Notice Notice of Layoff or Placement This section is to be completed by the agency human resource officer Agency Name Date Employee Employee ID Name Number Position Role SOC Code Number Pay Current Semi-Monthly Band Salary Effective , you are being placed in the following position: Role SOC Code Position Number Location Semi-Monthly Salary are being placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months because there is no placement opportunity available to you under the State Layoff Policy. If you are being placed, options available to you are marked with an X below. You may decline the placement if it requires relocating your residence, and proceed to the next placement opportunity available to you under the Layoff Policy, if any other options are available. If none are available, I will be placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months. You may decline the placement since it is to a position that will result in a salary decrease, and request that you be placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months. If you do not accept the placement, your only option is to be separated-layoff because it will not result in salary decrease or need to relocate. You will not be entitled to severance benefits. Signed Title This section is to be filled in by the employee and returned to the human resource officer no later than . If you do not return the form by this date, agency management will determine your placement. -

The Essential Guide to Handling a Layoff Table of Contents

Tools, tips, and templates to ensure a smooth transition The Essential Guide to Handling a Layoff Table of Contents Section One: How to Select Who to Layoff 05 Employee Layoff Selection Guide Multi–Criteria Layoff Selection Guide Section Two: Worker Adjustment & Retraining Notification 14 Checklist Sample Letter Section Three: How to Layoff an Employee 18 Reduction Checklist Layoff Script Layoff Letter / Layoff Memo / Layoff Form Severance Pay Policy / Severance Calculator Offboarding Checklist Exit Interview Questionnaire How to handle a layoff with confidence and care Careful planning and preparation are key to successfully managing a layoff. But too often, the day-to-day demands of a busy workplace leave little opportunity to put in place the information and materials that allow an employer to ease — for everyone involved — the turmoil a layoff can bring. That’s why this ebook has been created. Making the hard choices For managers and HR professionals, having to let people go is one of the most difficult parts of the job, even when it’s clear that it’s a necessary step. And for employees directly impacted by that decision, a layoff is not only difficult, but it can also initially be devastating, especially when loyal and productive employees have to be let go due to a company’s decision to downsize in order to remain viable. A reduction in force is also likely to affect the morale of the employees who remain on the job. As tough as layoffs can be, it is possible to do them in ways that make things easier on everyone — ways that illustrate for laid-off employees the fact that the company cares about them as people; ways that also leave remaining employees feeling reassured by the way a layoff has been handled. -

57 ARTICLE 26: LAYOFF A. General Provisions the Employer Shall

ARTICLE 26: LAYOFF A. General Provisions The Employer shall determine when temporary or indefinite layoffs are necessary. B. Definitions 1. Temporary layoff affecting a career position is for a specified period of less than four (4) calendar months from the date of layoff. 2. Indefinite layoff affecting a career position is one which is four (4) or more calendar months. C. Temporary Layoff 1. An employee shall be given written notice of the effective date and the ending date of a temporary layoff. The notice shall be given at least thirty (30) calendar days prior to the effective date. D. Indefinite Layoff 1. The order of layoff for indefinite career employees in the same classification (defined as the four (4) digits of the title code) within a unit defined by the Employer is in inverse order of seniority except that the department head may retain employees irrespective of seniority who possess special skills, knowledge, or abilities that are not possessed by other employees in the same classification with greater seniority, and that are necessary to perform the ongoing function of the department. 2. Seniority: Seniority shall be calculated by the number of career full-time equivalent months (or hours) of LLNL service. Employment prior to a break in service shall not be counted. When employees have the same number of full-time equivalent months (or hours), the employee with the most recent date of appointment shall be deemed the least senior. 3. Notice: An employee will receive at least thirty (30) calendar days written notice prior to indefinite layoff. If less than thirty (30) calendar days notice is provided, the employee shall receive straight-time pay in lieu of notice for each additional day the employee would have been on pay status had the employee been given thirty (30) calendar days notice.