The Archaeology of Food Preference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exotic Rivers of the World with Noble Caledonia

EXOTIC RIVERS OF THE WORLD WITH NOBLE CALEDONIA September 2015 to March 2016 Mekong – Irrawaddy – Ganges – Brahmaputra U2 Beinwww.noble-caledonia.co.uk Bridge, Amarapura +44 (0)20 7752 0000 SACRED RIVERS OF SOUTHEAST ASIA & INDIA No matter where you are in the world, exploring by river vessel is one of the most pleasurable ways of seeing the countryside and witnessing everyday life on the banks of the river you are sailing along. However in Southeast Asia and India it is particularly preferable. Whether you have been exploring riverside villages, remote communities, bustling markets or ancient sites and temples during the day, you can return each evening to the comfort of your vessel, friendly and welcoming staff, good food and a relaxing and convivial atmosphere onboard. Travelling by river alleviates much of the stress of moving around on land which, in Southeast Asia and India, can often be frustratingly slow as much of what we will see and do during our cruises can be approached from the banks of the river. Our journeys have been planned to incorporate contrasting and fascinating sites as well as relaxing interludes as we sail along the Mekong, Irrawaddy, Ganges or Brahmaputra. We are delighted to have chartered five small, unique vessels for our explorations which accommodate a maximum of just 56 guests. The atmosphere onboard all five vessels is friendly and informal and within days you will have made new friends in the open-seating restaurant, during the small-group shore excursions or whilst relaxing in the comfortable public areas onboard. You will be travelling amongst like-minded people but, for those who seek silence, there will always be the opportunity to relax in a secluded spot on the sun deck or simply relax in your well- appointed cabin. -

Kīrtimukha in the Art of the Kapili-Jamuna Valley of Assam: An

Kīrtimukha in the Art of the Kapili-Jamuna Valley of Assam: An Artistic Survey RESEARCH PAPER MRIGAKHEE SAIKIA PAROMITA DAS *Author affiliations can be found in the back matter of this article ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Mrigakhee Saikia The figure of thek īrtimukha or ‘glory- face’ is an artistic motif that appears on early Gauhati University, IN Indian art and architecture, initially as a sacred symbol and then more commonly as [email protected] a decorative element. In Assam, the motif of kīrtimukha is seen crowning the stele of the stray icons of the early medieval period. The motif also appeared in the structural components of the ancient and early medieval temples of Assam. The Kapili-Jamuna valley, situated in the districts of Nagaon, Marigaon and Hojai in central Assam houses TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Saikia, M and Das, P. 2021. innumerable rich archaeological remains, especially temple ruins and sculptures, Kīrtimukha in the Art of the both stone and terracotta. Many such architectural components are adorned by the Kapili-Jamuna Valley of kīrtimukha figures, usually carved in low relief. It is proposed to discuss the iconographic Assam: An Artistic Survey. features of the kīrtimukha motif in the art of the Kapili-Jamuna valley of Assam and Ancient Asia, 12: 2, pp. 1–15. also examine whether the iconographic depictions of the kīrtimukha as prescribed in DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ canonical texts, such as the Śilpaśāstras are reflected in the art of the valley. Pan Asian aa.211 linkages of the kīrtimukha motif will also be examined. INTRODUCTION Saikia and Das 2 Ancient Asia Quite inextricably, art in India, in its early historical period, mostly catered to the religious need of DOI: 10.5334/aa.211 the people. -

Archaeological Ruin Sites, Remains and Monuments in Assam

STUDY MATERIAL OF DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM OF TOURISM AND TRAVEL MANAGEMENT (T.T.M) BHATTADEV UNIVERSITY FOR SECOND (2ND) SEMESTER CLASS (B.A & B.SC) PAPER-DSC-1B-TTM-RC-2016-TOURISM RESORCES OF ASSAM UNIT-III-HISTORICAL AND RELIGIOUS TOURISM RESOURCES OF ASSAM Topic-ARCHAEOLOGICAL RUIN SITES, REMAINS AND MONUMENTS IN ASSAM Assam can be proud of her ancient and medieval archaeological remains and monuments. The first and the oldest specimen of sculpture of Assam have been found in the stone door-frame of a temple at Da-Parvatia near Tezpur town in the district of Sonitpur. This iconograph represents the Gupta-School of Art of the fifth and sixth centuries AD. Da-Parvatia Tezpur, like Guwahati is another town, which is archaeologically very rich. The first and the oldest specimen of sculpture or iconoplastic art of Assam have been found in the stone door frame of a temple at Da-Parvatia near Tezpur town in the district of Sonitpur. The earliest evidence of this group of ruins at Tezpur is the ruined Da Parvatia temple, belonging to 5th-6th century A.D., i.e. Gupta period. This brick built temple is in complete ruins and only the door frame is in standing position. The significance of the temple is the most beautiful door frame (dvara). Here, Ganga is depicted on the lower portion of a jamb, while Yamuna is depicted on the lower part of the other jamb. Both, the elegant figures of the river goddesses are well known amongst the art historians of country. Both, the jambs are minutely carved with miniature figures of human beings, birds, floral designs etc. -

Unit 6: Religious Traditions of Assam

Assamese Culture: Syncretism and Assimilation Unit 6 UNIT 6: RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS OF ASSAM UNIT STRUCTURE 6.1 Learning Objectives 6.2 Introduction 6.3 Religious Traditions of Assam 6.4 Saivism in Assam Saiva centres in Assam Saiva literature of Assam 6.5 Saktism in Assam Centres of Sakti worship in Assam Sakti literature of Assam 6.6 Buddhism in Assam Buddhist centres in Assam Buddhist literature of Assam 6.7 Vaisnavism in Assam Vaisnava centres in Assam Vaisnava literature of Assam 6.8 Let Us Sum Up 6.9 Answer To Check Your Progress 6.10 Further Reading 6.11 Model Questions 6.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you will be able to- know about the religious traditions in Assam and its historical past, discuss Saivism and its influence in Assam, discuss Saktism as a faith practised in Assam, describe the spread and impact on Buddhism on the general life of the people, Cultural History of Assam 95 Unit 6 Assamese Culture: Syncretism and Assimilation 6.2 INTRODUCTION Religion has a close relation with human life and man’s life-style. From the early period of human history, natural phenomena have always aroused our fear, curiosity, questions and a sense of enquiry among people. In the previous unit we have deliberated on the rich folk culture of Assam and its various aspects that have enriched the region. We have discussed the oral traditions, oral literature and the customs that have contributed to the Assamese culture and society. In this unit, we shall now discuss the religious traditions of Assam. -

History of Assam Upto the 16Th Century AD

GHT S5 01(M/P) Exam Code : HTP 5A History of Assam upto the 16th Century AD SEMESTER V HISTORY BLOCK 1 KRISHNA KANTA HANDIQUI STATE OPEN UNIVERSITY History of Assam up to the 16th century A.D.(Block 1) 1 Subject Experts 1. Dr. Sunil Pravan Baruah, Retd. Principal, B.Barooah College, Guwahati 2. Dr. Gajendra Adhikari, Principal, D.K.Girls’ College, Mirza 3. Dr. Maushumi Dutta Pathak, HOD, History, Arya Vidyapeeth College, Guwahati Course Coordinator : Dr. Priti Salila Rajkhowa, Asst. Prof. (KKHSOU) SLM Preparation Team UNITS CONTRIBUTORS 1,2,3,4 Muktar Rahman Saikia, St. John College Dimapur, Nagaland 5 Dr. Mridutpal Goswami, Dudhnoi College 6& 7 Dr. Mamoni Sarma, LCB College Editorial Team Content (English Version) : Prof. Paromita Das, Deptt. of History, GU Language (English Version) : Rabin Goswami, Retd. Professor, Deptt. of English, Cotton College Structure, Format & Graphics : Dr. Priti Salila Rajkhowa, KKHSOU June, 2019 © Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University This Self Learning Material (SLM) of the Krishna Kanta Handiqui State University is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License (International) : http.//creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0 Printed and published by Registrar on behalf of the Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University. Head Office : Patgaon, Rani Gate, Guwahati-781017; Web : www.kkhsou.in City Office: Housefed Complex, Dispur, Guwahati-781006 The University acknowledges with thanks the financial support provided by the Distance Education Bureau, UGC -

Juni Khyat ISSN: 2278-4632 (UGC Care Group I Listed Journal) Page

Juni Khyat ISSN: 2278-4632 (UGC Care Group I Listed Journal) Volume-X Issue-VIII, August 2020. Exploring the Potentialities and Strategies for Development of Tourism Industry in Assam Post Covid 19 Pandemic Ms. Banani Saikia, Assistant Professor, Department of Hospitality &Tourism Management, Assam down town University, Guwahati Dr. Sudhanshu Verma, Professor, Department of Management, Assam down town University, Guwahati Abstract Unprecedented present, unknown future. The year 2020 can safely be referred to as the year when human kind matured a lot and evolved even more. Various difficulties in various sectors due to Covid 19 Pandemic and because of continuous lock down, the global economy has been pushed into a recession. This pandemic is an epidemic which has affected all aspects of our lives without discerning between caste, creed, religion, social or monetary status, state of economy of a nation; everything is covered with this virus. Assam tourism industry is suffering a huge downfall and the travel agencies are facing a tremendous revenue loss and generated unemployment problem in the state. This study is an attempt to Identify the socio-economic importance of the tourism industry in the post Covid scenario, how to harness the various resources and assets, lying idle or underutilized because of Corona epidemic- pandemic and how to develop a strategy to revive tourism industry in the state of Assam, which has everything favoring the tourism but the tourists and that too because of Corona. Key Words: PESTEL analysis, SWOT analysis, tourism revival strategies, Introduction Unprecedented present, unknown future. The year 2020 can safely be referred to as the year when human kind matured a lot and evolved even more. -

Sustainable Heritage Tourism in India Knowledge Report Page 1 of 52 8Th India Heritage Tourism Conclave Mussoorie, March 2019

Sustainable Heritage Tourism in India Knowledge Report Page 1 of 52 8th India Heritage Tourism Conclave Mussoorie, March 2019 Page 2 of 52 TITLE Sustainable Heritage Tourism in India – Knowledge Report YEAR 2019 AUTHOR AUCTUS ADVISORS No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by photo, photo print, microfilm COPYRIGHT or any other means without the written permission of AUCTUS ADVISORS Pvt. Ltd. This report is the publication of AUCTUS ADVISORS Private Limited (“AUCTUS ADVISORS”) and so AUCTUS ADVISORS has editorial control over the content, including opinions, advice, statements, services, offers etc. that is represented in this report. However, AUCTUS ADVISORS will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by the reader’s reliance on information obtained through this report. This report may contain third-party contents and third-party resources. AUCTUS ADVISORS takes no responsibility for third part content, advertisements or third-party applications that are printed on or through this report, nor does it take any responsibility for the goods or services provided by its advertisers or for any error, omission, deletion, defect, theft or destruction or unauthorized access to, or alteration of, any user communication. Further, AUCTUS ADVISORS does not assume any responsibility or liability for any loss or damage, including personal injury or death, resulting from use of this report or from any content for communications or materials available on this report. The contents are provided for your reference only. The reader/ buyer understands that except for the information, products and services clearly identified as being supplied by AUCTUS ADVISORS, it does not operate, control or endorse any information, products, or services appearing in the report in any way. -

Influence of Buddhism in Sculptural Art of Assam: an Artistic Appreciation

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 11, Issue 4, April 2021 441 ISSN 2250-3153 Influence of Buddhism in Sculptural Art of Assam: An Artistic Appreciation Dr. Mousumi Deka Assistant Professor, Fine Arts Department The Assam Royal Global University, Guwahati DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.11.04.2021.p11259 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.11.04.2021.p11259 Abstract- The present paper focuses on the impact of Buddhism in sculptural art of Assam. A controversy has been continuing since antiquity on the existence of Buddhism in Assam. Though, mostly Brahmanism sculptures are observed in the temple sites of Assam, but the sculptures carry sometimes the message of Buddhism. Several archaeological sites display the image of Buddha and Buddhistic female goddess. Buddhism is closely related to Tantricism which was predominant in ancient Assam. Therefore, it is observed that image of Buddha is sometimes illustrated with the erotic figures. Index Terms- Assam, Buddhism, Tantricism, Temple, Sculptures I. INTRODUCTION Assam was prominent place for the sculptural activities in ancient time. Sculpture is closely related with the architecture where sculpture is used for decoration as well as religious significance. Temple plays a major role in the growth of the sculptural work. Three rulers namely Varman dynasty, Salastambha dynasty and Pala dynasty took responsibility to build temple architectures in ancient Assam in the period between 4th century AD - 12th century AD. But most of the temples are in ruin condition now. Numerous ancient temple sites display the Buddhistic sculptures along with the Brahmanical images. Ancient sculptures of Assam were usually influenced by Hinduism, but the sculptures reflect sometimes the influence of Buddhism, though Buddhism was not practised as a major religion in ancient Assam. -

14. Archaeology in North-East India

ARCHAEOLOGYIN NORttH― EASTiND:A Archaeologv in North-East lndia: The Post-lnd ependence scenario GAUTAM SENGUPTAAND SUKANYA SHARMA ABSTRACT The archaeological record of north-east lndia is distinctive in character. lt is a synthesis of two types of cultural traits: lndian and South-east Asian. Archaeological findings from the region known as Assam in the pre-lndependence period were reported from the beginning of the nineteenth century, but archaeological work was mainly done by enthusiastic administrators or tea planters who were interested in antiquities. The post- lndependence period is marked by problem-oriented research, with institutional involvement, in archaeology. But, till date, none of the universities in the region have an exclusive department of archaeology. The archaeology of the post-lndependence period in north-east lndia can be considered a social phenomenon in a particular historical context. lt is now widely recognized that all archaeology is political in that it involves relations of power and contemporary interventions in the production of the past. A new perspective in archaeology, 'the archaeology of the contemporary past', acknowledges a clear role for archaeology in bringing to light those aspects of history and contemporary erxperience that are explicily hidden from the public view by centres of authority, or are obscured by the absence of authority among individuals and groups within the political arena. This is referred to as 'presencing the absence'. lt is time for presencing the absence in north-east lndia -

Download Assam Geography GK PDF Part

ASSAM GEOGRAPHY GK 20 MOST IMPORTANT ASSAM1 GEOGRAPHY GK NewJobsinAssam.comPART(4) Q61) Which of the following is not connected by border of Assam: A) Bhutan B) Arunachal Pradesh C) Nagaland D) Sikkim NewJobsinAssam.com Q62) Which of the following district does not comes under the jurisdiction of BTC: A) Kokrajhar B) Bongaigaon C) Udalguri D) Chirang NewJobsinAssam.com Q63) Full form of APFBCS: |A) Assam Police Force Battalion |B) Assam Pradesh Fauzdar Betton Committee, Sivasagar C) Assam Project on Forest and Biodiversity Conservation Society D) Non NewJobsinAssam.comof the above Q64) Which is the only left tributary of Barak river: A) Lohit B) Sonai C) Jhanji D) Non of the above NewJobsinAssam.com Q65) Which is the Northward flow Sub River of Brahmaputra: A) Jhanji B) Padma C) Ganga D) Lohit NewJobsinAssam.com Q66) How much area of India is covered by Assam: A) 4.35% B) 4.36% C) 2.39% |D) 2.38% NewJobsinAssam.com Q67) Which country is located in the North of Assam: A) Nepal B) Bhutan C) China D) Bangladesh NewJobsinAssam.com Q68) How many district are there in Barak Valley A) Three B) Four C) Five D) One NewJobsinAssam.com Q69) Which of the following is the smallest national park in Assam: A) Manas National Park B) Orang National Park C) Nameri National Park D) Dibru Saikhowa National Park NewJobsinAssam.com Q70) Which of the following is the first North Eastern state carved out of Assam as a full fledged state: A) Arunachal Pradesh B) Meghalaya C) Nagaland D) MizoramNewJobsinAssam.com Q71) Area wise rank of Assam among North Eastern -

View Profile

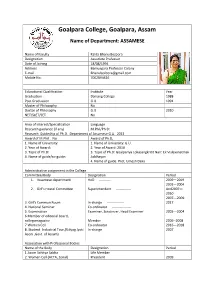

Goalpara College, Goalpara, Assam Name of Department: ASSAMESE Name of Faculty Kalita Bhanu Bezbora Designation Associate Professor Date of Joining 18/08/1994 Address Bamunpara Professor Colony E-mail [email protected] Mobile No. 7002894616 Educational Qualification Institute Year Graduation Darrang College 1988 Post Graduation G.U. 1991 Master of Philosophy No Doctor of Philosophy G.U 2010 NET/SLET/SET No Area of interest/Specialization Language Research guidance (if any) M.Phil/Ph.D: Research Guideship of Ph.D. Depertment of Assamese G.U. 2013 Award of M.Phil . No Award of Ph.D, 1. Name of University: 1. Name of University: G.U. 2. Year of Award: 2. Year of Award: 2010 3. Topic of Ph.D: 3. Topic of Ph.D: Goalpariya Lokasangkritit Nari: Ek Vislexanatmak 4. Name of guide/co-guide: Addhayan 4. Name of guide. Prof, Umesh Deka Administrative assignment in the College Committee/Body Designation Period 1. Assamese depertment HoD ---------- 2009—2019 2003—2004 2. Girl’s Hostel Committee Superintendent ------------- And2007— 2010 2007---2009 3. Girl’s Common Room In-charge --------------- 2017 4. National Seminar Co-ordinator ----------------- 5. Examination Examiner, Scrutinzer, Head Examiner 2003---2004 6.Member of editorial board, collegemagazine Member 2006--2008 7.Women Cell Co-ordinator 2016—2018 8. Student Industrial Tour,(Udyog Jyoti In-charge 2007 Asoni ,Govt. of Assam) Association with Professional Bodies Name of the Body Designation Period 1.Axom Sahitya Sabha Life Member 2. Women Cell (ACTA, Zonal) President 2009 3. Bharat Vikas Parisad Life Member 4.Ninad gosthi, G.U. Life Member 5.Member of editorial board,--Akash Member (Axom sahitya sabha women magazine) 2015---2017 6.Member of ACTA journal, Dudhnoi Adhibexan Member 2017 7.Member of Selection Committee, Subject Expert 2013 West Goalpara college 8. -

Ecotourism for Sustainable Development: a Case Study of Goalpara District in Assam

Volume : 3 | Issue : 4 | May 2013 ISSN - 2250-1991 Research Paper Geography Ecotourism for Sustainable Development: a Case Study of Goalpara District in Assam * Dr. M. Gopal Singha * Associate Professor, and HoD, Geography, Bikali College, Dhupdhara, Dist. Goalpara, Assam, Pin: 783123 ABSTRACT Ecotourism has become the most viable and sustainable way of deriving economic development in the world today. It has enormous potential for the socio-economic transformation of an area or region. Ecotourism has multidimensional implications, such as the protection of natural areas, generation of revenue, helping in conservation of environment and biological diversity and to bring forth sustainable development. Besides, having a great employment generating industry, tourism provides infrastructural and service facilities like transportation, communication, hospital, educational institution, hotel, motel, etc. Goalpara district, located in the South Western margin of the state of Assam in the neighborhood of Garo Hills in Meghalaya has enormous potential for ecotourism. But its development as a prospective sector has been hindered by geo-economic factors like transport and communication bottleneck, lack of public consciousness and government patronage. An attempt has been made in this paper to highlight the potentiality and problem of tourism. In the study available data on geo-ecological components relating to the district and economic parameters have also been used to draw overall view of ecotourism potentiality and problems thereof. Keywords : Viable, sustainable, transformation, geo-ecological. Introduction: ism are found in this district having sound heritage. Tourism Ecotourism refers to a neo-concept, which may be regarded in Goalpara district is based mainly on its natural grandeurs, as an ecologically responsible tourism.