(2018). Employability Skills in Studio Schools. Investigating the Use of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Years Foundation Stage Guidance

Early Years Foundation Stage Guidance Introduction Every child deserves the best possible start in life and the support that enables them to fulfil their potential. Children develop quickly in the early years and a child’s experiences between birth and age five have a major impact on their future life chances. A secure, safe and happy childhood is important in its own right. Good parenting and high quality early learning together provide the foundation children need to make the most of their abilities and talents as they grow up. (Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage DfE March 2017) The Early Years Foundation Stage applies to children from birth to the end of Reception. In our school children can join us at the beginning of the school year in which they are four, and if we have places some children are able to join us the term after they turn three. Key Stage One begins for our children at the beginning of Year One. We believe that the Early Years Foundation Stage curriculum is important in its own right and for preparing children for later schooling. It reflects the fact that children change and develop more rapidly in the first five years than at any other stage of their life. In order to ensure continuity and to enable each child to reach their full potential, we make a clear commitment to ensuring that the transition between pre-school and Nursery and Reception is made smoothly, so laying secure foundations for future learning. The early years education we offer is based upon The Early Years Foundation Stage statutory framework leading to the Early Learning Goals, which establish targets for most children to reach by the end of the Early Years Foundation Stage. -

The Dorset Studio School Special Educational Needs and Disabilities

The Dorset Studio School Special Educational Needs and Disabilities Information Report 1 Contents Special Educational Needs staff and contact details Page 6 What kind of special needs does the Dorset Studio School make provision for? Page 7 What type of support do we have at Dorset Studio School? Page 9 How do we identify and assess special educational needs and disabilities? Page 10 How do we measure the progress being made by our students with SEND? How do we know that our support works? Page 12 How does the Studio School support students with SEND through transition? Page 13 How do we ensure that students with SEND are not treated less favourably? Page 14 What extra-curricular activities can a student with SEND access at Dorset Studio School? Page 15 2 What training do Dorset Studio School staff have to help them support students with SEND? Page 15 How is the curriculum adapted for students with SEND? Page 16 How are parents of students with SEND involved in the education of their child? Page 17 How are students with SEND involved in their own education? Page 18 How do we deal with complaints by a parent of a student with SEND or by a student with SEND? Page 18 How does the governing body involve other people in meeting the needs of students with SEND including support for their families? Page 19 What provision is there for students who are looked after by the authority and have SEND? Page 20 How is the learning environment adapted for students with SEND? Page 20 How does the Dorset Studio School prevent bullying? Page 21 How does the Dorset Studio School get more specialist help if students need it? Page 21 3 Who are the support services that can help parents with children who have SEN? Page 21 Dorset’s Local Offer Page 22 Post-16 Information Page 23 4 Introduction The Dorset Studio School is designed to equip young people with the skills, knowledge and experience they require to succeed in the land and environmental sectors. -

School Organisation Data Supplement 2019 2 CONTENTS

School Organisation Data Supplement 2019 2 CONTENTS FIGURES AND CHARTS INDEX .............................................................................................................................. 4 PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 DEMOGRAPHIC AND OTHER FORECASTING DATA ....................................................................................... 7 1. NURSERY & EARLY YEARS PROVISION ....................................................................................................... 10 1.1 Existing Provision ................................................................................................................................ 10 1.2 Future Provision .................................................................................................................................. 11 2. PRIMARY ................................................................................................................................................................ 12 2.1 Existing Provision ................................................................................................................................ 12 2.2 Forecasting Influences ........................................................................................................................ 13 2.3 Future Trends ..................................................................................................................................... -

Special Educational Needs and Disability Information

STEPHENSON STUDIO SCHOOL SPECIAL EDUCATIONAL NEEDS AND DISABILITY INFORMATION What kinds of special educational needs does the school make provision for? Stephenson Studio School welcomes students with special educational needs as defined by the new SEND Code of Practice 2014. We expect students to access mainstream lessons and activities, with support, where necessary. Stephenson Studio School caters for a wide range of Special Educational Needs, Disabilities and medical needs. These include ASD, dyslexia, ADHD, physical difficulties such as hypermobility, diabetes and emotional difficulties. Working closely with parents and professionals we will always seek to teach every child so they can achieve his or her best. How does the school know if students need extra help and what should I do if I think that my child may have special educational needs? Progress and achievement is rigorously tracked and the data is used to identify both underachievement and lack of progress. We gather information from: KS2 teacher assessments including SATs results Primary Annual Reviews and transition meetings EHC Plan documentation Information from outside agencies including ADHD Solutions, Behaviour Support Service, Educational Psychology Service and the Autism Outreach Team Baseline Assessments in English, maths and science, including standardised literacy testing Where we have concerns about progress we will seek advice from other agencies as appropriate. When a child is transferring from a different setting a process is put in place to ensure successful transition. Within the school the progress of every child is carefully tracked and any concerns due to these assessments, or professional observations, will be raised with the parent by the Tutor, Personal Coach or SENDCO. -

Opening a Studio School a Guide for Studio School Proposer Groups on the Pre-Opening Stage

Opening a studio school A guide for studio school proposer groups on the pre-opening stage August 2014 Contents Introduction 3 Section 1 - Who does what - roles and responsibilities? 5 Section 2 - Managing your project 10 Section 3 – Governance 12 Section 4 - Pupil recruitment and admissions 21 Section 5 - Statutory consultation 33 Section 6 - Staffing and education plans 36 Section 7 - Site and buildings 42 Section 8 – Finance 56 Section 9 - Procurement and additional support 63 Section 10 - Funding Agreement 67 Section 11 - The equality duty 71 Section 12 - Preparing to open 73 Section 13 - Once your school is open 80 Annex A - RSC regions and Local authorities 82 2 Introduction Congratulations! All your planning and preparation has paid off, and the Secretary of State for Education has agreed that your application to open a studio school should move to the next stage of the process – known as the ‘pre-opening’ stage. This is the stage between the approval of your application and the opening of the school. The setting up of a studio school is a challenging but ultimately very rewarding task and it will require significant commitment and time from sponsors and partners. Your original application set out your plans for establishing the studio school, from the education vision and the admission of pupils to the recruitment of staff and the curriculum. Now your application has been approved, you must begin work to implement these plans. The letter of approval you received from the Department for Education (DfE) sets out important conditions of approval. It is vital that you consider these conditions carefully in planning your priorities and what you need to focus on next. -

Induction & Virtual Tour for New Parents

EDISON PRIMARY SCHOOL IGNITING YOUNG MINDS TODAY FOR A BRIGHTER TOMORROW WELCOME TO NEW RECEPTION PARENTS NOVEMBER 2020 Leadership Team • Chair of Governors – Kamal Kainth • Headteacher – Amrit Dokal • Deputy Headteacher – Hardeep Rupra • EYFS Leader – Deepika Rahman Our Vision • High expectations and challenge for all pupils It is the supreme art of the teacher to awaken joy in creative expression and knowledge. Albert Einstein • Visible Science and Practical learning Science is not only a disciple of reason but, also, one of romance and passion. Stephen Hawking • A Broad Curriculum The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character - that is the goal of true education. Martin Luther King, Jr. At the end of the day, the most overwhelming key to a child's success is the positive involvement of parents. Jane D. Hull When Can My Child Start School? Date of birth Start or transfer Apply 01/09/2016- Start Reception Sept 2021 1 Sept 2020 – 15 Jan 31/08/2017 2021 Key Dates: Date Activity September to December 2020 Parents can contact primary schools to make virtual viewings (if available). 15 January 2021 Closing date for receipt of online applications. 8 February 2021 Closing date for applications from people moving into the borough, or changing address after 15 January 2020. By 8 March 2021 Applications are ranked according to admissions criteria. 16 April 2021 Offer day, letters are posted to applicants who applied using a paper form. Parents who applied online will be able to view the outcome of their application from the evening of 16 April. -

Parent Handbook

Parent Handbook Willow Nest Studio, Inc. 592 16th Street, Brooklyn, NY 11218 P: 646-236-3116 Email: [email protected] www.willowneststudio.com Willow Nest Studio Introductory Information Willow Nest Studio, Inc is a NY State Licensed and insured Group Family Day Care Provider that operates in a studio space on the second floor of a Windsor Terrace dwelling. In September of 2015, the owner and founder of this childcare facility, Elisha Georgiou, obtained this license from the New York State Office of Children and Family Services while designing her home-based studio school. This license serves to allow Willow Nest Studio, Inc. to best provide playgroup services and arts enrichment classes to toddlers, preschool aged-children, and also school-aged children. Story Tree Playgroup is a drop-off, home-based preschool alternative program at the Willow Nest Studio space in Windsor Terrace Brooklyn. Elisha Georgiou is the founder, director, provider and head teacher at Story Tree Playgroup and the owner of Willow Nest Studio. In addition to holding a NY State license to provide child care in her residence, she also holds a Masters of Education from Teacher’s College, Columbia University. Story Tree Playgroup is a mixed-age environment admitting children between ages 2.5- 4.5. We suggest 3-4 days of enrollment per week, with a minimum of three hours per day and a maximum of six hours per day. Elisha is supported by one assistant when working with children more than 6 in number. All teachers are screened by the NYC Department of Health including fingerprinting and background check. -

Dowling College, New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting & Sculpture and Glasgow Caledonian New York College

THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT / THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK / ALBANY, NY 12234 TO: The Honorable the Members of the Board of Regents FROM: Elizabeth R. Berlin SUBJECT: Conferral of Degrees: Dowling College, New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting & Sculpture and Glasgow Caledonian New York College DATE: August 29, 2019 AUTHORIZATION(S): SUMMARY Issue for Decision (Consent Agenda) Should the Board of Regents confer degrees upon students successfully completing programs at Dowling College, New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting & Sculpture and Glasgow Caledonian New York College? Reason(s) for Consideration Required by State statute and State regulation. Proposed Handling This question will come before the full Board at its September 2019 meeting, where it will be voted on and action taken. Background Information Section 208 of the Education Law gives the Regents the authority to make awards in certain circumstances. By statute and regulation, institutions of higher education that have provisional charters do not have authority to award degrees. Until such time as a charter is made absolute, the Board of Regents awards degrees on behalf of provisionally chartered institutions. In the case of closed institutions of higher education, in order to hold students harmless, the Board of Regents awards degrees to eligible students who complete the requirements for their registered degree programs at other institutions, for specified periods of time. BR (CA) 2 Dowling College Dowling College, which was located at 150 Idle Hour Boulevard in Oakdale, New York, was granted an absolute charter by the Board of Regents on September 27, 1968. On August 31, 2016, Dowling College closed. -

Kindergarten Parent Guide

Kindergarten Guide www.adams12.org/kindergarten We are excited to welcome new kindergarten students and their families into our district community. The beginning of kindergarten is a major time of transition for both children and their families. The information provided here was compiled by parents for parents in the hopes that it will answer your questions and help you and your child feel prepared and excited to begin the school journey. It’s true! Kindergarten provides all students the first experience of their academic career. While there is still a strong emphasis on your student’s social-emotional development, the kindergarten experience in Adams 12 Five Star Schools provides every student with rigorous academic programs necessary to develop a strong foundation that will help them succeed as they progress through their elementary and secondary school career. HOW OLD DOES MY CHILD NEED TO BE TO START KINDERGARTEN? Your child must be 5 years old on or before Oct. 1 of the school year he/she will start school. If your child misses the cut-off date but is a highly advanced gifted student (at or above 98th percentile on nationally normed assessments as per Colorado Department of Education guidelines), you can apply for early entrance. For more GIFTED & information on early entrance, please visit www.adams12.org/kindergarten. TALENTED HOW DO I KNOW WHAT SCHOOL MY CHILD SHOULD ATTEND? The district has school boundaries based on geography. To find what elementary school your child should attend, SCHOOL please visit www.adams12.org/boundary-locator. BOUNDARY WHAT IF I WANT TO CHOOSE MY CHILD’S SCHOOL? You can check for information on the district’s website regarding which schools are open for Choice. -

RECOMMENDED to CABINET Education Travel Policy for the Academic Year 2020-21

RECOMMENDED TO CABINET Education Travel Policy for the academic year 2020-21 This applies to: • All state-funded schools in Devon. • The Transport Co-ordination Service of Devon County Council. • All parents and carers of Devon-resident children of statutory school age or Rising 5s seeking transport assistance to and from an education setting. Policy updated: October 2018 Review date: October 2019 for 2021-22 and then annually unless a need to review earlier is identified Description of Policy This policy describes how eligibility for transport to and from education settings will be determined and how transport will be provided. Linked Policies In-Year, Normal Round Co-ordinated Admissions Schemes 2020 Education Travel Policy – updated 31 January 2019 © Devon County Council 2019 If this document is printed, it may not be the most up-to-date version. This will be available at www.devon.gov.uk/admissionarrangements Page 1 Education Travel Policy for the academic year 2020-21 Section Contents Page General Information and Contacts 4 Summary 5 Policy 1 Equality Statement 7 2 Safeguarding Statement 7 3 Introduction 7 4 Section A – children below statutory school age 8 5 Section B – children of statutory school age at a primary school 9 6 Section C – children of statutory school age at a secondary school 11 7 Section D – children and young people with special educational needs 14 8 Section E – further information 15 8.1 Roles and responsibilities of the parent 15 8.2 Applications for transport assistance 16 8.3 Roles and responsibilities of -

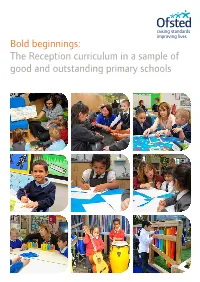

Bold Beginnings

Bold beginnings: The Reception curriculum in a sample of good and outstanding primary schools In January 2017, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector (HMCI) commissioned an Ofsted-wide review of the curriculum. Its aim was to provide fresh insight into leaders’ curriculum intentions, how these are implemented and the impact on outcomes for pupils. This report shines a spotlight on the Reception Year and the extent to which a school’s curriculum for four- and five-year-olds prepares them for the rest of their education and beyond. 2 Bold beginnings – November 2017, No. 170045 Contents Executive summary 4 Key findings 5 Recommendations 7 Reception – a unique and important year 8 The curriculum 12 Teaching 16 Language and literacy 19 Mathematics 24 Assessment and the early years foundation stage profile 26 Initial teacher education 29 Methodology 31 Annex A: Schools visited 32 Annex B: Online questionnaire 34 3 www.gov.uk/ofsted Executive summary A good early education is the foundation for later supposed to teach it. This seemed to stem from success. For too many children, however, their misinterpreting what the characteristics of effective Reception Year is a missed opportunity that can leave learning in the early years foundation stage (EYFS)2 – them exposed to all the painful and unnecessary ‘playing and exploring, active learning, and creating consequences of falling behind their peers. and thinking critically’ – required in terms of the curriculum they provided. During the summer term 2017, Her Majesty’s Inspectors (HMI) visited successful primary schools The EYFS profile (EYFSP)3 is a mechanism for statutory in which children, including those from disadvantaged summative assessment at the end of the foundation backgrounds1, achieved well. -

Establishing and Leading New Types of School: Challenges and Opportunities for Leaders and Leadership

Inspiring leaders to improve children’s lives Schools and academies � Establishing and leading new types of school: challenges and opportunities for leaders and leadership Resource Contents � Acknowledgements ..........................................................................................................................3 � Executive summary .........................................................................................................................4 � 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................................8 � 2: Methodology .............................................................................................................................12 � 3: Key lessons from research on setting up and leading new schools .......................................14 � 4: Establishing new types of school: the role of school leaders .................................................20 � 5: Leadership in new types of school ............................................................................................34 � 6: Role of promoters and governors in the leadership of new types of school .........................52 � 7: New types of school and their partnership networks .............................................................59 � 8: Professional skills and development of leaders of new types of school ................................66 � 9: Recommendations .....................................................................................................................78