Chapter 5 the Super Proton Synchrotron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Il Nostro Mondo

IL NOSTRO MONDO THE DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION AND PERFORMANCE OF THE CERN INTERSECTING STORAGE RINGS (ISR) A RECOLLECTION OF WORLD’S FIRST PROTON-PROTON COLLIDER KURT HÜBNER CERN, Geneva, Switzerland 1 Design which had a beam energy of 160 MeV. The interaction points to increase the collision rate The concept of colliding beams appeared design of these colliders started in 1957. but without special lattice insertions as one first in a German patent by Rolf Widerøe In 1961, the Accelerator Research Group would use these days. registered in 1943 and published in 1952. Division was expanded into the Accelerator Combined-function magnets were chosen However, at that time the intensity of beams Division as experienced manpower had as in the PS, i.e. the main magnets had a was too low for an exploitable collision rate as become available after the running-in of the magnetic dipole field to bend the beam and a beam accumulation had not yet been invented. PS in 1960. At the same time it was decided quadrupole field to focus the beam. This type The first ideas of a realistic design were to construct a small accelerator to test rf of magnet provided space for the elaborate published in 1956 by Gerard O’Neill and by the stacking, a technique to be experimentally pole-face windings foreseen to control the MURA Group lead by Donald Kerst in the USA. proven, as it was essential for the performance magnetic field to a very high precision. It also MURA had come up with beam accumulation and success of the ISR. -

Pos(ICRC2019)446

New Results from the Cosmic-Ray Program of the NA61/SHINE facility at the CERN SPS PoS(ICRC2019)446 Michael Unger∗ for the NA61/SHINE Collaborationy Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Postfach 3640, D-76021 Karlsruhe, Germany E-mail: [email protected] The NA61/SHINE experiment at the SPS accelerator at CERN is a unique facility for the study of hadronic interactions at fixed target energies. The data collected with NA61/SHINE is relevant for a broad range of topics in cosmic-ray physics including ultrahigh-energy air showers and the production of secondary nuclei and anti-particles in the Galaxy. Here we present an update of the measurement of the momentum spectra of anti-protons produced in p−+C interactions at 158 and 350 GeV=c and discuss their relevance for the understanding of muons in air showers initiated by ultrahigh-energy cosmic rays. Furthermore, we report the first results from a three-day pilot run aimed at investigating the ca- pability of our experiment to measure nuclear fragmentation cross sections for the understanding of the propagation of cosmic rays in the Galaxy. We present a preliminary measurement of the production cross section of Boron in C+p interactions at 13.5 AGeV=c and discuss prospects for future data taking to provide the comprehensive and accurate reaction database of nuclear frag- mentation needed in the era of high-precision measurements of Galactic cosmic rays. 36th International Cosmic Ray Conference -ICRC2019- July 24th - August 1st, 2019 Madison, WI, U.S.A. ∗Speaker. yhttp://shine.web.cern.ch/content/author-list c Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). -

NA61/SHINE Facility at the CERN SPS: Beams and Detector System

Preprint typeset in JINST style - HYPER VERSION NA61/SHINE facility at the CERN SPS: beams and detector system N. Abgrall11, O. Andreeva16, A. Aduszkiewicz23, Y. Ali6, T. Anticic26, N. Antoniou1, B. Baatar7, F. Bay27, A. Blondel11, J. Blumer13, M. Bogomilov19, M. Bogusz24, A. Bravar11, J. Brzychczyk6, S. A. Bunyatov7, P. Christakoglou1, T. Czopowicz24, N. Davis1, S. Debieux11, H. Dembinski13, F. Diakonos1, S. Di Luise27, W. Dominik23, T. Drozhzhova20 J. Dumarchez18, K. Dynowski24, R. Engel13, I. Efthymiopoulos10, A. Ereditato4, A. Fabich10, G. A. Feofilov20, Z. Fodor5, A. Fulop5, M. Ga´zdzicki9;15, M. Golubeva16, K. Grebieszkow24, A. Grzeszczuk14, F. Guber16, A. Haesler11, T. Hasegawa21, M. Hierholzer4, R. Idczak25, S. Igolkin20, A. Ivashkin16, D. Jokovic2, K. Kadija26, A. Kapoyannis1, E. Kaptur14, D. Kielczewska23, M. Kirejczyk23, J. Kisiel14, T. Kiss5, S. Kleinfelder12, T. Kobayashi21, V. I. Kolesnikov7, D. Kolev19, V. P. Kondratiev20, A. Korzenev11, P. Koversarski25, S. Kowalski14, A. Krasnoperov7, A. Kurepin16, D. Larsen6, A. Laszlo5, V. V. Lyubushkin7, M. Mackowiak-Pawłowska´ 9, Z. Majka6, B. Maksiak24, A. I. Malakhov7, D. Maletic2, D. Manglunki10, D. Manic2, A. Marchionni27, A. Marcinek6, V. Marin16, K. Marton5, H.-J.Mathes13, T. Matulewicz23, V. Matveev7;16, G. L. Melkumov7, M. Messina4, St. Mrówczynski´ 15, S. Murphy11, T. Nakadaira21, M. Nirkko4, K. Nishikawa21, T. Palczewski22, G. Palla5, A. D. Panagiotou1, T. Paul17, W. Peryt24;∗, O. Petukhov16 C.Pistillo4 R. Płaneta6, J. Pluta24, B. A. Popov7;18, M. Posiadala23, S. Puławski14, J. Puzovic2, W. Rauch8, M. Ravonel11, A. Redij4, R. Renfordt9, E. Richter-Wa¸s6, A. Robert18, D. Röhrich3, E. Rondio22, B. Rossi4, M. Roth13, A. Rubbia27, A. Rustamov9, M. -

Improving the Slow Extraction Efficiency of the CERN Super

Improving the slow extraction efficiency of the CERN Super Proton Synchrotron Brunner Kristóf Faculty of Science Eötvös Loránd University Supervisors: Barna Dániel, Wigner RCP Christoph Wiesner, CERN May 2018 Contents 1 Introduction4 2 CERN accelerator complex5 2.1 Accelerators..................................... 5 2.2 Experiments..................................... 6 2.2.1 Colliders .................................. 7 2.2.2 Fixed target experiments.......................... 7 2.3 Current and future demands of fixed target experiments.............. 7 3 Introduction to accelerator physics9 3.1 History of linear and circular accelerators ..................... 9 3.2 Design orbit, focusing................................. 11 3.3 Betatron oscillation, the behaviour of single particles ................ 11 3.4 The Twiss-ellipse, the behaviour of the beam ................... 13 3.5 Normalised phase space............................... 15 3.6 Tune and resonances ................................ 16 4 Extraction from a synchrotron 19 4.1 Fast extraction.................................... 19 4.2 Multi-turn extraction ................................ 20 4.3 Sextupole driven slow extraction........................... 21 4.4 Possible enhancements............................... 24 4.4.1 Diffuser................................... 24 4.4.2 Dynamic bump............................... 26 4.4.3 Phase space folding............................. 26 5 Massless septum 28 5.1 Method of phase space folding using a massless septum.............. 29 6 Simulation -

Montecarlo Simulations Using GRID

UNIVERSITADEGLISTUDIDITORINO` Facolt`a di Scienze Matematiche, Fisiche e Naturali Dottorato di ricerca in Fisica XVII Ciclo Spin asymmetries for the reaction µD → µΛXat COMPASS: MonteCarlo simulations using GRID Candidato Antonio Amoroso Relatore Prof.ssa Maria Pia Bussa Coordinatore del ciclo Prof. Ezio Menichetti 2002-2004 0.1. Introduction i 0.1 Introduction COMPASS (COmmon Muon and Proton Apparatus for Structure and Spec- troscopy) [1] is a complex experimental apparatus assembled by an interna- tional collaboration of more than 20 Institutions. Two research physics pro- grams have been planned. One centered on muon physics and the other one on hadron physics. COMPASS is a fixed target experiment in the North Area site at CERN. It uses beams produced by the SPS accelerator. The experiment is placed in the EHN2 hall (Bldg. 888) in the Prevessin (F) site of CERN. The purpose of the experiment is the study of the structure and the spectroscopy of hadrons using different high intensity beams of lepton and hadrons with energies ranging from 100 to 200 GeV. The experiment aims to collect large samples of charmed particles. From the measurement of the cross section asymmetry for open charm production in deep inelastic scattering of polarized muons on polarized nucleons, the gluon polarization ∆G will be determined and compared with the available theoretical predictions. Hadron beams are used to study the semi-leptonic decays of charmed doubly charmed baryons. Both measurements will allow to study fundamental prob- lems regarding the hadron structure and to test Heavy Quark Effective Theory (HQET) calculations. Moreover the production of exotic states, which are fore- seen by the QCD but have not yet been established, will investigated. -

Particle Physics Lecture 4: the Large Hadron Collider and Other Accelerators November 13Th 2009

Subatomic Physics: Particle Physics Lecture 4: The Large Hadron Collider and other accelerators November 13th 2009 • Previous colliders • Accelerating techniques: linacs, cyclotrons and synchrotrons • Synchrotron Radiation • The LHC • LHC energy and luminosity 1 Particle Acceleration Long-lived charged particles can be accelerated to high momenta using electromagnetic fields. • e+, e!, p, p!, µ±(?) and Au, Pb & Cu nuclei have been accelerated so far... Why accelerate particles? • High beam energies ⇒ high ECM ⇒ more energy to create new particles • Higher energies probe shorter physics at shorter distances λ c 197 MeV fm • De-Broglie wavelength: = 2π pc ≈ p [MeV/c] • e.g. 20 GeV/c probes a distance of 0.01 fm. An accelerator complex uses a variety of particle acceleration techniques to reach the final energy. 2 A brief history of colliders • Colliders have driven particle physics forward over the last 40 years. • This required synergy of - hadron - hadron colliders - lepton - hadron colliders & - lepton - lepton colliders • Experiments at colliders discovered W- boson, Z-boson, gluon, tau-lepton, charm, bottom and top-quarks. • Colliders provided full verification of the Standard Model. DESY Fermilab CERN SLAC BNL KEK 3 SppS̅ at CERNNo b&el HERAPrize for atPhy sDESYics 1984 SppS:̅ Proton anti-Proton collider at CERN. • Given to Carlo Rubbia and Simon van der Meer • Ran from 1981 to 1984. Nobel Prize for Physics 1984 • Centre of Mass energy: 400 GeV • “For their decisive • 6.9 km in circumference contributions to large • Two experiments: -

The Search for Charged Massive Supersymmetric Particles at the LHC

The Search for Charged Massive Supersymmetric Particles at the LHC Aleksey Pavlov A Senior Project Presented to Cal Poly June 5, 2012 This material is based upon work supported by The National Science Foundation under grant number 0969966. 1 Contents 1 Abstract 3 2 Introduction 3 3 Supersymmetry: An Extension of the Standard Model 5 4 CHAMPs 8 5 The LHC 9 6 The ALICE Detector 12 7 Analysis 14 8 Results 17 2 1 Abstract Charged Massive Particles (CHAMPs) are predicted in the Supersymmetry (SUSY) extension of the Standard Model though they have never been ob- served. We look for CHAMPs in the ALICE Detector at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN. While the main purpose of ALICE is to study Quark- Gluon Plasma, we take advantage of the tracking and time of flight capabil- ities of several sub-detectors in ALICE to look for signs of CHAMPs. These elusive particles are characterized by their slow velocity, high transverse mo- mentum and therefore heavy mass. Our research found a small handful of candidates among a large sample size but more work is required to confirm their identity and exclude the possibility that they have been misidentified. 2 Introduction The Standard Model of Particle Physics (SM) is the modern theory describ- ing how fundamental particles interact and behave. It was developed in the second half of the 20th Century after physicist Sheldon Glashow found a way to combine, or unify, the electromagnetic and electroweak forces [7]. In 1973 Glashow's electroweak theory was experimentally confirmed at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Geneva, Switzerland, when nuetral currents through the weak nuclear force were measured. -

Cern: a European Laboratory for the World

CERN: A EUROPEAN LABORATORY FOR THE WORLD G.K. Mallot CERN THE BEGINNINGS 1949: Proposal by de Broglie to the Eur. Cult. Conf. "the creation of a laboratory or institution where it would be possible to do scientific work, but somehow beyond the framework of the different participating states” “undertake tasks, which, by virtue of their size and cost, were beyond the scope of individual countries" 1952: Interim council: Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire left council members : Pierre Auger, Edoardo Amaldi and Lew Kowarski 1953: Geneva chosen as location G. K. Mallot Yamagata/ 24 September 2008 2 THE BEGINNINGS 1954: European Organization for Nuclear Research 12 founding European Member States Belgium, Denmark, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Yugoslavia foundation stone laying 10 June 1955 by DG Felix Mission: Bloch • provide for collaboration among European States in nuclear research of a pure scientific and fundamental character • have no concern with work for military requirements • the results of its experimental and theoretical work shall be published or otherwise made generally available . G. K. Mallot Yamagata/ 24 September 2008 3 A GOBAL ENDEAVOUR > half of world’s particle physicists G. K. Mallot Yamagata/ 24 September 2008 4 CERN IN NUMBERS 2500 staff 9000 users (192 from Japan) 800 fellows and associates 580 universities, 85 nations Budget 987MCHF (93 GJPY) 20 Member States: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, 7 Observers: the Slovak Republic, Spain, India, Israel, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland and the Russian Federation, Turkey, the United Kingdom. -

Simulation of Hydrodynamic Tunneling Induced by High-Energy Proton Beam in Copper by Coupling Computer Codes

PHYSICAL REVIEW ACCELERATORS AND BEAMS 22, 014501 (2019) Editors' Suggestion Simulation of hydrodynamic tunneling induced by high-energy proton beam in copper by coupling computer codes † ‡ Y. Nie,1,* C. Fichera,1 L. Mettler,1, F. Carra,1 R. Schmidt,1, N. A. Tahir,2 A. Bertarelli,1 and D. Wollmann1 1CERN, CH-1211 Geneva 23, Switzerland 2GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany (Received 18 October 2018; published 11 January 2019; corrected 31 January 2019) The design of machine protection systems for high-energy accelerators with high-intensity beams requires analyzing a large number of failures leading to beam loss. One of the most serious failures is an accidental impact of a large number of bunches at one location, for example, due to a deflection of the particle beams by the extraction kicker magnets with the wrong strength. The numerical assessment of such an event requires an iterative execution of an energy-deposition code and a hydrodynamic code, in case the hydrodynamic tunneling effect plays an important role in the beam-matter interactions. Such calculations have been performed for the CERN Large Hadron Collider (LHC), since the energy stored in the LHC beams exceeds previous accelerators by 2 orders of magnitude. This was done using the particle shower code FLUKA and the hydrodynamic code BIG2 [Tahir et al., Phys. Rev. STAccel. Beams 15, 051003 (2012)]. Later, simulations for a number of cases for other accelerators at CERN and the Future Circular Collider (FCC) were performed [Tahir et al., Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 19, 081002 (2016)]. These simulations showed that the penetration depth of the beam in copper or graphite could be an order of magnitude deeper when considering the hydrodynamic tunneling, compared to a static approximation. -

THE PROTON-ANTIPROTON COLLIDER Lecture Delivered at CERN on 25 November 1987 Lyndon Evans

CERN 88-01 11 March 1988 ORGANISATION EUROPÉENNE POUR LA RECHERCHE NUCLÉAIRE CERN EUROPEAN ORGANIZATION FOR NUCLEAR RESEARCH CERN ACCELERATOR SCHOOL Third John Adams Memorial Lecture THE PROTON-ANTIPROTON COLLIDER Lecture delivered at CERN on 25 November 1987 Lyndon Evans GENEVA 1988 ABSTRACT The subject of this lecture is the CERN Proton-Antiproton (pp) Collider, in which John Adams was intimately involved at the design, development, and construction stages. Its history is traced from the original proposal in 1966, to the first pp collisions in the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) in 1981, and to the present time with drastically improved performance. This project led to the discovery of the intermediate vector boson in 1983 and produced one of the most exciting and productive physics periods in CERN's history. RN —Service d'Information Scientifique-RD/757-3000-Mars 1988 iii CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. BEAM COOLING l 3. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE pp COLLIDER CONCEPT 2 4. THE SPS AS A COLLIDER 4 4.1 Operation 4 4.2 Performance 5 5. IMPACT OF EARLIER CERN DEVELOPMENTS 5 6. PROPHETS OF DOOM 7 7. IMPACT ON THE WORLD SCENE 9 8. CONCLUDING REMARKS: THE FUTURE OF THE pp COLLIDER 9 REFERENCES 10 Plates 11 v 1. INTRODUCTION The subject of this lecture is the CERN Proton-Antiproton (pp) Collider and let me say straightaway that some of you might find that this talk is rather polarized towards the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS). In fact, the pp project was a CERN-wide collaboration 'par excellence'. However, in addition to John Adams' close involvement with the SPS there is a natural tendency for me to remain within my own domain of competence. -

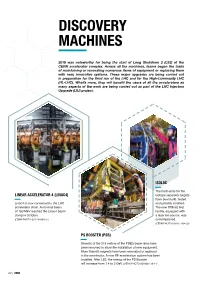

Discovery Machines

DISCOVERY MACHINES 2019 was noteworthy for being the start of Long Shutdown 2 (LS2) of the CERN accelerator complex. Across all the machines, teams began the tasks of maintaining or renovating numerous items of equipment or replacing them with new, innovative systems. These major upgrades are being carried out in preparation for the third run of the LHC and for the High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC). What’s more, they will benefit the users of all the accelerators as many aspects of the work are being carried out as part of the LHC Injectors Upgrade (LIU) project. ISOLDE The front-ends for the LINEAR ACCELERATOR 4 (LINAC4) isotope separator targets have been built, tested Linac4 is now connected to the LHC and partially installed. accelerator chain. A nominal beam The new Offline2 test of 160 MeV reached the Linac4 beam facility, equipped with dump in October. a laser ion source, was (CERN-PHOTO-201704-093-27) commissioned. (CERN-PHOTO-201911-394-28) PS BOOSTER (PSB) Seventy of the 215 metres of the PSB’s beam lines have been removed to allow the installation of new equipment. More than 60 magnets have been renovated or replaced in the accelerator. A new RF acceleration system has been installed. After LS2, the energy of the PS Booster will increase from 1.4 to 2 GeV. (CERN-PHOTO-201906-149-11) 22 | CERN SUPER PROTON SYNCHROTRON (SPS) LARGE HADRON COLLIDER (LHC) A new RF acceleration system is under The electrical insulation of the diodes has construction. The SPS beam dump is being been completed on 94% of the accelerator’s replaced. -

Charged Pion Spectra in Proton–Carbon Interactions at 31 Gev/C

XIII International Workshop on Neutrino Factories, Super beams and Beta beams (NUFACT11) IOP Publishing Journal of Physics: Conference Series 408 (2013) 012048 doi:10.1088/1742-6596/408/1/012048 Charged pion spectra in proton–carbon interactions at 31 GeV/c Magdalena Zofia Posiada la on behalf of the NA61/SHINE Collaboration Faculty of Physics, University of Warsaw, Ho˙za69, 00-681 Warsaw, Poland E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The NA61/SHINE experiment at CERN SPS measured charged pion spectra in p+C interactions at 31 GeV/c. These measurements are necessary to improve predictions of the neutrino flux for the T2K long baseline neutrino oscillation experiment in Japan. Presented analysis was based on the data collected during the first NA61/SHINE run in 2007 with an isotropic graphite target with a thickness of 4% of nuclear interaction length. Three different methods which were used in order to obtain π+ and π− spectra are introduced. Differential cross sections for negatively and positively charged pions are presented as a function of laboratory momentum in ten intervals of the laboratory polar angle up to 420 mrad. 1. Introduction The NA61/SHINE (SHINE = SPS Heavy Ion and Neutrino Experiment) is a large acceptance hadron spectrometer located in the North Area H2 beam line of the European Centre for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Geneva. The experiment uses beams from the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS). The NA61/SHINE experiment combines a rich physics program in three different fields: auxiliary measurements for neutrino experiments, cosmic-ray simulations, and the behavior of strongly interacting matter at high density (see: [1, 2, 3] for details).