“The Old First Is with the South:”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

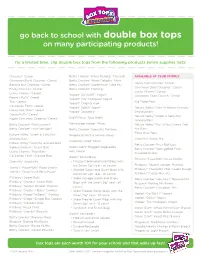

Go Back to School with Double Box Tops on Many Participating Products!

go back to school with double box tops on many participating products! for a limited time, clip double box tops from the following products (while supplies last): Cheerios® Cereal Betty Crocker® Warm Delights® Desserts AVAILABLE AT CLUB STORES: Cinnamon Burst Cheerios® Cereal Betty Crocker® Warm Delights® Minis Honey Nut Cheerios® Cereal Banana Nut Cheerios® Cereal Betty Crocker® SuperMoist® Cake Mix Cinnamon Burst Cheerios® Cereal Fruity Cheerios® Cereal Betty Crocker® Frosting Lucky Charms® Cereal Lucky Charms® Cereal Yoplait® Go-GURT® Yogurt Cinnamon Toast Crunch® Cereal Reese’s Pus® Cereal Yoplait® Trix® Multipack Yogurt Trix® Cereal Kid Triple Pack Yoplait® Original 4-pk Cascadian Farm® Cereal Yoplait® Splitz® Yogurt Nature Valley® Oats ‘N Honey Crunchy Honey Nut Chex® Cereal Yoplait® Smoothie Granola Bars Cocoa Pus® Cereal Nature Valley® Sweet & Salty Nut Apple Cinnamon Cheerios® Cereal Old El Paso® Taco Shells Granola Bars Betty Crocker® Fruit Gushers® Hamburger Helper® Mixes Nature Valley® Fruit & Nut Chewy Trail Betty Crocker® Fruit Roll-Ups® Betty Crocker® Specialty Potatoes Mix Bars Fiber One® Bars Nature Valley® Sweet & Salty Nut Progresso® Rich & Hearty Soups Granola Bars Chex Mix® Snack Mix Suddenly Salad® Mixes Nature Valley® Crunchy Granola Bars Betty Crocker® Fruit Roll-Ups® Golden Graham® Snack Bars Green Giant® Bagged Vegetables Betty Crocker® SpongeBob Fruit- Lucky Charms® Treat Bars with Sauce Flavored Snacks Cascadian Farm® Granola Bars Ziploc® brand Bags : Totino’s® Pizza Rolls® Pizza Snacks Chex Mix® Snack Mix -

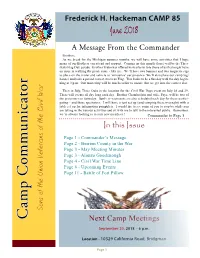

Newsletter 3

x Frederick H. Hackeman CAMP 85 June 2018 A Message From the Commander Brothers, As we break for the Michigan summer months, we will have some activities that I hope many of our Brothers can attend and support. Coming up this month (June) will be the Three Oaks Flag Day parade. Brother Truhn has offered his trailer to tote those of us that might have an issue in walking the prade route - like me. We’ll have two banners and two magnetic sigs to place on the trailer and vehicle to ‘announce’ our presence. We’ll also place our camp lag/ banner and have a period correct Amrican Flag. This looks to be a fun day with the day begin- ning at 3 p.m. Our mustering will be much earlier to ensure that we get into the correct slot. Then in July, Three Oaks is the location for the Civil War Days event on July 28 and 29. War There will events all day long each day. Brother Chamberlain and wife, Faye, will be two of the presenters on Saturday. Battle re-eactments are also scheduled each day for those partici- pating - and those spectators. I will have a tent set up (and camping there overnght) with a table set up for information pamphlets. I would ike to see some of you to stop by while you are taking in the various activities and sit with me to talk to the interested public. Remember, we’re always looking to recruit new members ! Commander to Page 5 In this Issue Page 1 - Commander’s Message Page 2 - Berrien County in the War Page 3 - May Meeting Minutes Page 3 - Alonzo Goodenough Veterans of the Civil Page 4 - Civil War Time Line Page 6 - Upcoming Events Page 11 - Battle of Fort Pillow Sons of the Union Camp Communicator Next Camp Meetings September 20, 2018 - 6 p.m. -

Topography Along the Virginia-Kentucky Border

Preface: Topography along the Virginia-Kentucky border. It took a long time for the Appalachian Mountain range to attain its present appearance, but no one was counting. Outcrops found at the base of Pine Mountain are Devonian rock, dating back 400 million years. But the rocks picked off the ground around Lexington, Kentucky, are even older; this limestone is from the Cambrian period, about 600 million years old. It is the same type and age rock found near the bottom of the Grand Canyon in Colorado. Of course, a mountain range is not created in a year or two. It took them about 400 years to obtain their character, and the Appalachian range has a lot of character. Geologists tell us this range extends from Alabama into Canada, and separates the plains of the eastern seaboard from the low-lying valleys of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Some subdivide the Appalachians into the Piedmont Province, the Blue Ridge, the Valley and Ridge area, and the Appalachian plateau. We also learn that during the Paleozoic era, the site of this mountain range was nothing more than a shallow sea; but during this time, as sediments built up, and the bottom of the sea sank. The hinge line between the area sinking, and the area being uplifted seems to have shifted gradually westward. At the end of the Paleozoric era, the earth movement are said to have reversed, at which time the horizontal layers of the rock were uplifted and folded, and for the next 200 million years the land was eroded, which provided material to cover the surrounding areas, including the coastal plain. -

List of Staff Officers of the Confederate States Army. 1861-1865

QJurttell itttiuetsity Hibrary Stliaca, xV'cni tUu-k THE JAMES VERNER SCAIFE COLLECTION CIVIL WAR LITERATURE THE GIFT OF JAMES VERNER SCAIFE CLASS OF 1889 1919 Cornell University Library E545 .U58 List of staff officers of the Confederat 3 1924 030 921 096 olin The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030921096 LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES ARMY 1861-1865. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1891. LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE ARMY. Abercrombie, R. S., lieut., A. D. C. to Gen. J. H. Olanton, November 16, 1863. Abercrombie, Wiley, lieut., A. D. C. to Brig. Gen. S. G. French, August 11, 1864. Abernathy, John T., special volunteer commissary in department com- manded by Brig. Gen. G. J. Pillow, November 22, 1861. Abrams, W. D., capt., I. F. T. to Lieut. Gen. Lee, June 11, 1864. Adair, Walter T., surg. 2d Cherokee Begt., staff of Col. Wm. P. Adair. Adams, , lieut., to Gen. Gauo, 1862. Adams, B. C, capt., A. G. S., April 27, 1862; maj., 0. S., staff General Bodes, July, 1863 ; ordered to report to Lieut. Col. R. G. Cole, June 15, 1864. Adams, C, lieut., O. O. to Gen. R. V. Richardson, March, 1864. Adams, Carter, maj., C. S., staff Gen. Bryan Grimes, 1865. Adams, Charles W., col., A. I. G. to Maj. Gen. T. C. Hiudman, Octo- ber 6, 1862, to March 4, 1863. Adams, James M., capt., A. -

John Larue Helm (1802-1867) by Steven Lindsey

John LaRue Helm (1802-1867) By Steven Lindsey In recognition of his service during the revolutionary war, Thomas Helm was granted a parcel of 1000 acres on Beargrass Creek near the Falls of the Ohio. He moved his family to this location in the fall of 1779, but after several children and Negroes died of spotted fever, he decided to move his family to the south. The Helm family migrated to Severns Valley in the spring of 1780. Andrew Hynes and Samuel Haycraft, along with several other families, were in his company. Helm, Hynes and Haycraft built stockade forts on the hilltops overlooking Severns Valley and marking the future location of Elizabethtown. George Helm, the son of Thomas, was just six years old when his family arrived in Kentucky. In 1784, John and Mary Brooks LaRue emigrated from the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and settled along the Nolin River near the present day Hodgenville. Their daughter, Rebecca, was only a baby when her family brought her to Kentucky. Andrew Hynes donated 30 acres for a new village. In honor of his contribution, it was named after his wife, Elizabeth. The streets of Elizabethtown were laid out in 1797. George Helm and Rebecca LaRue were married on May 14, 1801 and their first child, John LaRue Helm, was born on July 4, 1802, probably at Rebecca’s parents’ home near present day Hodgenville. John was a naturally bright and inquisitive child. He attended various schools in Hardin County until he was 14 years old. Due to financial difficulties within his family, his education in the public schools ended at the 8th grade and he went to work on the family farm. -

Harden-In-Ing Famnily Assn. Mem·Bers Descendants of Mark Hardin and Mary Hogue

HARDEN-IN-ING FAMNILY ASSN. MEM·BERS DESCENDANTS OF MARK HARDIN AND MARY HOGUE F /' y'" .s +- 1> I r a 'j ~ s 0 f- r hQ If- i/ (} 'P8 i(. )/~t oP #F/f (V1.Q.."rrlbQ.rs. D~Q,s Fro~ j"r1 a Y" I< H c1 rd J 'v") <f-. Yn ~ r 'f 1-103 lI' Q..... UP f h. /" (..I ~ib' $f'v a b ~ /,.) f. 2...&7 e;, "I ' w: II d -0 0 f her p;;z Ii ~:> IL a c. A. cL d I.f . 6~m:s~ INDEX OF HFA MEMBERS AND DIRECT LiNEAGES IN 31 KNOWN GROlJP ., NO. IN GROUP PAG.E AG (desc of Asher Garner Hardin b. c 1814 AL) , 12 309(a) B-NC' (" with roots in.Bertie Co., NC mid 1700s) ,10 141 C-SS ( "" " in C'entral-Southside, VA late 1600s-early 1700s)' 70 290 EN (" ofH~rdens roots i"n PA area 1700s) . -:',).-'1J L~~ G-CUL (" of George Hardin b.1755 Culpepper Co., VA) 6 31: G-NC ( "of Harden-ins with roots in Guilford Co., NC mid 1700s) 35 128 ~:ciJHC (" of Hardins on Hif:kory Creek Co. -now Cleveland Co.- NC late 170Qs) '83 1(J4 HIH (" of Hiram Hardin b. 1796 TN) .' 8 330' HS (" of Henry Hardin d. 1783 m. Elizabeth Sealey, Chester Co., NC ) 36 278 IMM ( "ofHHH from known immigrants to the USA) 38 268 J-AL (" of Jacob Hardin b. 1766 NC, lived Pike Co., AL 1850) ~:L ,:1: .~JXVIf/tt.itcItTlCJE (" of John Hardin b. -

Daniel D. Pratt: Senator and Commissioner

Daniel D. Pratt: Senator and Commissioner Joseph E. Holliday* The election of Daniel D. Pratt, of Logansport, to the United States Senate in January, 1869, to succeed Thomas A. Hendricks had come after a bitter internal struggle within the ranks of the Republican members of the Indiana General Assembly. The struggle was precipitated by James Hughes, of Bloomington, who hoped to win the honor, but it also uncovered a personal feud between Lieutenant Governor Will E. Cumback, an early favorite for the seat, and Governor Conrad Baker. Personal rivalries threatened party harmony, and after several caucuses were unable to reach an agreement, Pratt was presented as a compromise candidate. He had been his party’s nominee for a Senate seat in 1863, but the Republicans were then the minority party in the legislature. With a majority in 1869, however, the Republicans were able to carry his election. Pratt’s reputation in the state was not based upon office-holding ; he had held no important state office, and his only legislative experience before he went to Washington in 1869 was service in two terms of the general assembly. It was his character, his leadership in the legal profession in northern Indiana, and his loyal service as a campaigner that earned for him the esteem of many in his party. Daniel D. Pratt‘s experience in the United States Senate began with the inauguration of Ulysses S. Grant in March, 1869. Presiding over the Senate was Schuyler Colfax, another Hoosier, who had just been inaugurated vice-president of the United States. During the administration of President Andrew Johnson, the government had been subjected to severe stress and strain between the legislative and executive branches. -

Copyright by CLP Research 1600 1700 1750 1800 1850 1650 1900 Partial Genealogy of the Todds, Part II 2 Main Political Affiliatio

Copyright by CLP Research Partial Genealogy of the Todds, Part II Main Political Affiliation: (of Kentucky & South Dakota) 1763-83 Whig/Revolutionary 1789-1823 Republican 1824-33 National Republican 1600 1834-53 Whig 1854- Republican 2 1650 John Todd (1667-1719) (born Ellerlise, Lanarkshire, Scotland); (moved to Drumgare, Derrymore Parish, County Armagh, Ireland) = Rose Cornell (1670s?-at least 1697 Samuel Todd 3 Others Robert Todd William Todd (1697-1760)) (1697-1775) (1698-1769) (Emigrated from County Armagh, Ireland to Pennsylvania, 1732) (Emigrated from County Armagh, Ireland to Pennsylvania, 1732) = Jean Lowe 1700 (moved to Virginia) Ann Smith = = Isabella Bodley Hamilton (1701-at least 1740) See Houston of NC = Ann Houston (1697-1724) (1697-1739) Genealogy (1698-at least 1736) 1 Son David Todd 9 Children 5 Others Sarah Todd (1723-85); (farmer) 6 Others Lydia Todd (1727-95) (Emigrated from Ireland with father); (moved to Kentucky to join sons, 1784) (1736-1812) = John Houston III = Hannah Owen = James M. McKee (1727-98) (1720-1805) (1726-78) (moved to Tennessee) See McKee of KY See Houston of NC 5 Others Lt. Levi Todd Genealogy 1750 Genealogy (1756-1807); (lawyer) (born Pennsylvania); (moved to Kentucky, 1776); ((Rev War with Gen. George Rogers Clark/Kaskaskia) (clerk, KY district court, controlled by Virginia, 1779; of Fayette co. KY, part of VA, 1780-1807 Jane Briggs = = Jane Holmes (1761-1800) (1779-1856) Dr. John Todd I 8 Others Robert Smith Todd 1 Son (1787-1865) (1791-1849) (born Kentucky); (War of 1812) (clerk, KY house, 1821-41); (president, Bank of Kentucky, Lexington branch) (moved to Illinois) (KY house, 1842-44); (KY senate, 1845-49) 1800 = Elizabeth Fisher Smith of PA Eliza Ann Parker = = Elizabeth Humphreys (1793-1865) (1794-1825) (1801-74) 5 Others Gen. -

Find Box Tops on Hundreds of Products You Know and Love TM RECORTA BOX TOPS ¡Y RECAUDA DINERO PARA TU ESCUELA!

CLIPPING IS EASY! Find Box Tops on hundreds of products you know and love TM RECORTA BOX TOPS ¡Y RECAUDA DINERO PARA TU ESCUELA! It’s easy to find Box Tops. In fact, you may have some in your home right now. Clip Box Tops from your favorite products and turn them into your school today! Box Tops are each worth 10¢ and they add up fast! Encontrar Box Tops es fácil. De hecho, tal vez tengas algunos en tu casa en este momento. Recorta Box Tops de cientos de tus productos favoritos. Cada cupón de Box Tops tiene un valor de 10¢ para tu escuela ¡y esas cantidades se suman rápido! BAKING & BAKEWARE HornEAdo y producTos para hOrNear HousEhold clEANing limpieza del hogar ScHool & office supplieS artículos para escuEla y oficina • Betty Crocker™ Baking & Cake Mixes • Finish® Dishwashing Detergent • Boise Polaris® Paper • Betty Crocker™ Brownies & Dessert Mixes • Lysol® Disinfecting Spray • Betty Crocker™ Complete Pancake • Lysol® Hand Soap • Betty Crocker™ Create ‘n’ Bake Cookies BoCAdIllos • Betty Crocker™ Frosting snacks & JuIcEs • Betty Crocker™ FUN da-Middles • Annie’s® Cookies • Betty Crocker™ Gluten Free Mixes Meals & sideS CoMidas y guarnIcionEs • Annie’s® Crackers • Betty Crocker™ Muffin & Cookie Mixes • Annie’s® Mac & Cheese • Annie’s® Fruit Snacks • Betty Crocker™ Pizza Crust Mix • Annie’s® Microwaveable Mac & Cheese Cups • Annie’s® Granola Bars • Bisquick™ • Betty Crocker™ Bowl Appetit • Annie’s® Snack Mix • Fiber One™ Mixes • Betty Crocker™ Hamburger, Chicken & • Betty Crocker™ Fruit Flavored Snacks • Reynolds® Genuine Parchment Paper -

A University Microfilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

The Iron Furnace

5ft if %&h THE IRON FURNACE: OR, . SLAYERY AND SECESSION. BY REV. JOHN H. AUGHEY, A REFUGEE FROM MISSISSIPPI. Cursed be the man that obeyeth not the words of this covenant, which I commanded your fathers in the day that I brought them forth out of the land of Egypt, from the Iron Furnace Jer. xi. 3, 4. See also, 1 Kings viii. 51. PHILADELPHIA: WILLIAM S. & ALFRED MARTIEN. 606 CHESTNUT STREET. 1863. Entered, according to the Act of Congress, in the year 1863, By WILLIAM S. & ALFRED MARTIEN, In the office of the Clerk of the District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. i:45S . a. ; m TO MY PERSONAt FRIENDS REV. CHARLES C. BEATTY, D. D., LL.D.,' OF STEUBENVILLE, OHIO, Moderator of the General Assembly of the (0. S.) Presby- terian Church in the United States of America, and long Pastor of the Church in which my parents were members, and our family worshippers REV. WILLIAM PRATT BREED, Pastor of the West Spruce Street Presbyterian Church, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; GEORGE HAY STUART, Esq., OF PHILADELPHIA, PA., The Philanthropist, whose virtues are known and appreciated in both hemispheres, THIS VOLUME IS AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED. PREFACE. " A celebrated author thus writes : Posterity- is under no obligations to a man who is not a parent, who has never planted a tree, built a house, nor written a book." Having fulfilled all these requisites to insure the remembrance of posterity, it remains to be seen whether the author's name shall escape oblivion. It may be that a few years will obliterate the name affixed to this Preface from the memory of man.