Corresponding Romantic Metaphors in the Poetry of WB Yeats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Creating a Dream for Religious Life in the 21St Century

Blessing and Hope: Creating a Dream for Religious Life in the 21st Century Donna J. Markham, OP, PhD Religious Formation Conference November 12-15, 2009 _______________ When we are dreaming alone it is only a dream. When we are dreaming with others, it is a beginning of reality. --Dom Helder Camara There is a fascinating body of psychodynamic work that has been developing since the early 1980s through the pioneering work of W. Gordon Lawrence and Mary Dluhy. It is called “social dreaming” and, in some wonderfully metaphoric and rather mysterious manner, it invites participants to activate both the power of the community and the power of the dream to create a new communal culture. While this involves a very detailed group process much too complex to explain now, I would like to share with you some of the central tenets of this creative development. You will also note that it bears some similarities to Peter Block’s work on community. In a more traditional understanding of communal culture, a community focuses its efforts along two dimensions: on its life and mission as it is experienced as a process in real time and on its life and mission as it is in the process of becoming. That is, how do we evaluate our current state of affairs and what might we surmise about how we will be in the future? To concretize this a bit, if we were to look at common ways in which we enter into chapter deliberations, financial planning or various other decision-making strategies, we typically examine how 1 things are going now and in what ways we see things developing and plan accordingly. -

Full Orchestra 2021.Pdf

Full Orchestra Title Composer Catalog # Grade Price Title Composer Catalog # Grade Price Φ A La Manana ..................................../Leidig; Niehaus ............49063 .....E .........45.00 Artist's Life, Op. 316 ...........................Strauss, Jr./Muller .........38001 .....MD ......80.00 Φ Aboriginal Rituals ...............................DelBorgo ......................30172 .....M.........59.00 As Summer Was Just Beginning Abduction from the Seraglio: Overture ..Mozart/Meyer ...............33192 .....ME ......59.00 (Song for James Dean) ....................Daehn ...........................49044 .....M.........68.00 Φ Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 ..Brahms/Bergonzi ..........30328 .....M.........73.00 As Time Goes By ...............................Hupfeld/Lewis ...............13708 .....MD ......50.00 Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 ..Brahms/Leidig ..............33029 .....MD ......73.00 Ashford Celebration ...........................Ford ..............................30240 .....MD ......60.00 Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 ..Brahms/Muller ..............38000 .....MD ......45.00 Φ Ashokan Farewell ...............................Ungar/Cerulli ................47093 .....ME ......65.00 Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 ..Brahms/Simpson ..........57085 .....D .........90.00 Ashton Place ......................................Niehaus ........................49051 .....MD ......60.00 Academic Procession .........................Daniels .........................60005 .....ME ......55.00 Aspen Fantasy ...................................Feese -

Pianodisc Music Catalog.Pdf

Welcome Welcome to the latest edition of PianoDisc's Music Catalog. Inside you’ll find thousands of songs in every genre of music. Not only is PianoDisc the leading manufacturer of piano player sys- tems, but our collection of music software is unrivaled in the indus- try. The highlight of our library is the Artist Series, an outstanding collection of music performed by the some of the world's finest pianists. You’ll find recordings by Peter Nero, Floyd Cramer, Steve Allen and dozens of Grammy and Emmy winners, Billboard Top Ten artists and the winners of major international piano competi- tions. Since we're constantly adding new music to our library, the most up-to-date listing of available music is on our website, on the Emusic pages, at www.PianoDisc.com. There you can see each indi- vidual disc with complete song listings and artist biographies (when applicable) and also purchase discs online. You can also order by calling 800-566-DISC. For those who are new to PianoDisc, below is a brief explana- tion of the terms you will find in the catalog: PD/CD/OP: There are three PianoDisc software formats: PD represents the 3.5" floppy disk format; CD represents PianoDisc's specially-formatted CDs; OP represents data disks for the Opus system only. MusiConnect: A Windows software utility that allows Opus7 downloadable music to be burned to CD via iTunes. Acoustic: These are piano-only recordings. Live/Orchestrated: These CD recordings feature live accom- paniment by everything from vocals or a single instrument to a full-symphony orchestra. -

V-By Song Title

V6C030 Christmas Prayer L. Adams V8D002 Folk Dances Of Latin America (C.D.) D. Cavalier V6A065 Run Children Run S. Hatfield V7B126 "B Is For Bully: 1 T. Ed. , 16 st. ed. A. Gotlib & A. Brass V7B126C "B Is For Bully: Accompaniment Tape A. Gotlib & A. Brass V7B127D "Bugz"- Performance & Accompaniment CD J. Jacobson & J. Higgins V7B127 "Bugz"- Teachers Manual- Repro Pack J. Jacobson & J. Higgins V1D123 c.1 "Cats"- Vocal Selections Hal Leonard V1D123 c.2 "Cats"- Vocal Selections Hal Leonard V6D004 "Joy To The World"- 15 Sacred Carols for Christmas- John Rutter Hinshaw V7B129 "The Family Feud"- Teacher's Manual with Performance & Accompaniment CD L. Fiftal V1B111 (A) The Big Red Bus (B) Grandfather Clock V1B117 (A) The Squirrel (B) Little Silver Fishes T. Dunhill V5D *See V4D002 Reflections of Canada Vol.2 (SSA, SAT, SAB) V7D001 …And A Glass Slipper L. I. Fallis V1D013 120 Christmas Songs (Voice and Piano) D. Nelson V1D050 40 French Hits of Our Times (Bk. 7) MCA V1D067 60 Silly Songs R. Edison V1B068 A Bag of Tools J.L. Hodd V4A023 A Blessing S. Porterfield V1C029 A Carol of Peace E. Thiman V6A061 A Celtic Prayer B. Peters V6C027 A Child Is Born M. Weir V3B231 A Child of Song D. Herring/ A. Beck V3A062 A Child's Credo Greg Gilpin V3B146 A Child's Hope M. Donnelly V1C002 A Christmas Carol J. Broeck V7C005 A Christmas Carol B. Treharne V7C046 A Christmas Carol L. Averill V7C065 c.1 A Christmas Carol J. Higgins V7C065 c.2 A Christmas Carol J. -

Corkscrew Pointe

Corkscrew Pointe Artist Title Disc Number Track # 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10218 master 2 These Are The Days 10191 Master 1 Trouble Me 10191 Master 2 10Cc I'm Not In Love 10046 master 1 The Things We Do For Love 10227 Master 1 112 Dance With Me (Radio Version) 10120 master 112 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 10104 master 12 1910 Fruitgum Co. 1, 2, 3 Red Light 10124 Master 1910 2 Live Crew Me So Horny 10020 master 2 We Want Some P###Y 10136 Master 2 2 Pac Changes 10105 master 2 20 Fingers Short #### Man 10120 master 20 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 10131 master 3 Be Like That (Radio Version) 10210 master 3 Kryptonite May 06 2010 3 Loser 10118 master 3 311 All Mixed Up Mar 23 2010 311 Down 10209 Master 311 Love Song 10232 master 311 38 Special Caught Up In You 10203 38 Rockin' Into The Night 10132 Master 38 Teacher, Teacher 10130 Master 38 Wild-eyed Southern Boys 10140 Master 38 3Lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) (Radio 10127 Master 1 Version) 4 Non Blondes What's Up 10217 master 4 42Nd Street (Broadway Version) 42Nd Street 10227 Master 2 1 of 216 Corkscrew Pointe Artist Title Disc Number Track # 42Nd Street (Broadway Version) We're In The Money Mar 24 2010 14 50 Cent If I Can't 10104 master 50 In Da Club 10022 master 50 Just A Lil' Bit 10136 Master 50 P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 10092 master 50 Wanksta 10239 master 50 50 Cent and Mobb Deep Outta Control (Remix Version) 10195 master 50 50 Cent and Nate Dogg 21 Questions 10105 master 50 50 Cent and The Game How We Do (Radio Version) 10236 master 1 69 Boyz Tootsee Roll 10105 master 69 98° Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 10016 master 4 I Do (Cherish You) 10128 Master 1 A Chorus Line What I Did For Love (Movie Version) 10094 master 2 A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) May 04 2010 1 A Perfect Circle Judith 10209 Master 312 The Hollow 10198 master 1 A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie 10213 master 1 A Taste Of Honey Sukiyaki 10096 master 1 A Teens Bouncing Off The Ceiling (Upside Down) 10016 master 5 A.B. -

1 February 2008 SCHOOL DISTRICT 41 BURNABY ELEMENTARY

February 2008 SCHOOL DISTRICT 41 BURNABY ELEMENTARY CHORAL MUSIC INVENTORY LISTED ALPHABETICALLY BY TITLE Title Composer Arranger Publisher # of copies Voicing Location “Hello” from Around the World Lantz/Lantelli Shawnee 19 2 part Gilpin 22 Favorite Folksongs R. Pisans Hollis Music 3 Gilmore A Cause for Mrs. Claus Gallina Jenson 23 SS Westridge A Child’s Prayer to the Shepherd William France Frederick Harris 2 2-part Lakeview A Children’s Noel Charles Yannerella Sacred Music 1 2-part Lakeview A Christmas Alleluia Audrey Snyder Studio 1 2-part Lakeview World Library of A Christmas Ballad Virginia E. Witterkind 1 2-part Lakeview Sacred Music A Christmas Carol Higgins Hal Leonard 15 SS Westridge A Christmas Eve Prayer Richard Oliver Richmond 1 2-part Lakeview A Christmas Greeting Donnelly/Strid Donnelly/Strid Hal Leonard 10 2 part Aubrey World Library of A Christmas Legend William Siden 1 Solo or unison Lakeview Sacred Music A Christmas Party Polka R.W. Thygerson Richmond Music 8 2 part Brantford A Cookie for Snip (& The Tired Burton Keith Burton Keith Leslie 10 Unison Kitchener Moon) A Cookie For Snip/Tired Moon Burton Burth Leslie 1 Unison Lakeview A Distant Shore Mary Donnelly George Strid Alfred Choral 13 2 part Brentwood A Gift for Every Child Sally K. Albrecht Alfred Choral 19 SA Nelson A Gift of Love We Bring Robert Graham Columbia Pictures 1 2-part Lakeview A Great Big Sea Lori-Anne Dolloff Boosey & Hawkes 1 Unison Marlborough A Kyrie for Our Time Don Besig Shawnee 26 2 part Douglas Road A La Femme Ruth Watson Henderson Gordon V. -

Center for Responsible Lending Public Citizen National Consumer Law Center (On Behalf of Its Low Income Clients) Consumer Federa

Center for Responsible Lending Public Citizen National Consumer Law Center (on behalf of its low income clients) Consumer Federation of America American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) Americans for Financial Reform Education Fund Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) NAACP National Association for Latino Community Asset Builders National Coalition for Asian Pacific American Community Development (National CAPACD) U.S. PIRG Comments to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Notice of Proposed Rulemaking Payday, Vehicle Title, and Certain High-Cost Installment Loans Proposed Rescission of Ability-to-Repay Rule 12 CFR Part 1041 Docket No. CFPB-2019-0006 RIN 3170-AA80 May 15, 2019 Submitted electronically to https://www.regulations.gov Comment Intake Consumer Financial Protection Bureau 1700 G Street NW Washington, DC 20552 1 The Center for Responsible Lending (CRL) is a nonprofit, non-partisan research and policy organization dedicated to protecting homeownership and family wealth by working to eliminate abusive financial practices. CRL is an affiliate of Self-Help, one of the nation’s largest nonprofit community development financial institutions. Over 37 years, Self-Help has provided over $7 billion in financing through 146,000 loans to homebuyers, small businesses, and nonprofits. It serves more than 145,000 mostly low-income members through 45 retail credit union locations in North Carolina, California, Florida, Greater Chicago, and Milwaukee. Public Citizen, Inc., is a consumer-advocacy organization founded in 1971, with members in all 50 states. Public Citizen advocates before Congress, administrative agencies, and the courts for the enactment and enforcement of laws protecting consumers, workers, and the general public. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 17/12/2016 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 17/12/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs (H?D) Planet Earth My One And Only Hawaiian Hula Eyes Blackout I Love My Baby (My Baby Loves Me) On The Beach At Waikiki Other Side I'll Build A Stairway To Paradise Deep In The Heart Of Texas 10 Years My Blue Heaven What Are You Doing New Year's Eve Through The Iris What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry Long Ago And Far Away 10,000 Maniacs When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Bésame mucho (English Vocal) Because The Night 'S Wonderful For Me And My Gal 10CC 1930s Standards 'Til Then Dreadlock Holiday Let's Call The Whole Thing Off Daddy's Little Girl I'm Not In Love Heartaches The Old Lamplighter The Things We Do For Love Cheek To Cheek Someday You'll Want Me To Want You Rubber Bullets Love Is Sweeping The Country That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Life Is A Minestrone My Romance That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) 112 It's Time To Say Aloha I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET Cupid We Gather Together Aren't You Glad You're You Peaches And Cream Kumbaya (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 12 Gauge The Last Time I Saw Paris My One And Only Highland Fling Dunkie Butt All The Things You Are No Love No Nothin' 12 Stones Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Personality Far Away Begin The Beguine Sunday, Monday Or Always Crash I Love A Parade This Heart Of Mine 1800s Standards I Love A Parade (short version) Mister Meadowlark Home Sweet Home I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter 1950s Standards Home On The Range Body And Soul Get Me To The Church On -

English 1 - a English No

SONG LIST FOR MULTMEDIA KARAOKE PLAYER ENGLISH 1 - A ENGLISH NO. TITLE SINGER NO. TITLE SINGER 6624 V 1 2 3 Gloria Estefan 1344 A Dear John Letter Keith Green 2852 10 Guitars Engelbert Humperdinck 8 A Different Beat Boyzone 1240 100 Years Five For Fighting 1625 A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 2 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 6791 V A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 1834 12 Days Of Christmas Ray Conniff 3540 A Friend Keno 3559 18 Life Skid Row 9 A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins 3 19 Hundred And 85 Paul Mccartney 2270 A Girl's Gotta Do Mindy Mccready 3538 1985 Bowling for soup 6658 V A Girl's Gotta Do(What A Girl'... Mindy Mccready 3560 1999 Prince 3567 A Groovy Kind Of Love Wayne Fontana 932 2 Be 3 Philipe Goyon 1345 A Guy Is A Guy Doris Day 5380 2 Be 3 Philipe Goyon 3568 A Hard Day's Night Beatles 5382 2 Be 3 Philipe Goyon 6098 V A Hard Day's Night Beatles 3561 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 3569 A Haze Shade Of Winter Bangles 7042 V 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 3410 A Heart Like Mine Gospel 2858 2 In A Million S Club 7 3570 A Horse With No Name America 3562 2 Times Ann Lee 10 A House Is Not A Home Dionne Warwick 3563 2001 C C Rider Elvis Presley 2271 A House With No Curtains Alan Jackson 2810 214 Rivermaya 7363 V A House With No Curtains Alan Jackson 3539 214 (Improved Version) Rivermaya 3398 A Kind Of Magic Queen 3564 25 Minutes Michael Learns To Rock 11 A Little Bit More Dr Hook 7469 V 25 Minutes Michael Learns To Rock 2272 A Little Bit More Abba 3565 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 6484 V A Little Bit Of You Lee Roy Parnell 4 4 + 20 CSN & Y 7393 V A Little Gasoline -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Literary

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of The Study Literary text contains a potentiality for tranforming the whole system that it embodies and that has produced it. Literary text is able to subvert the linguistic system it inherits, it doest not merely exhibit the characteristic form of the language which contains it, it also extends and modifies that language1 Literature is a canon which consists of those works in language by which a community defines itself through the course of its history. It include works primarily artistic and also those whose aesthetic qualities are only secondary2. Literature is a word in the English language; like all words, literary texts. It is used by perhaps millions of speakers, speakers who come from vastly different backgrounds and who have quite divergent personal experiences with, and views on, literary text3. The very word “music” comes from the Greek word mousikos, meaning “of the muses” (the Greek goddesses who inspired poets, painters, 1 Sanusi, Ibrahim Chinade,” Structuralism as a Literary Theory: An Overview,” 124- 131(March, 2012), 128. 2 Jim Meyer, “What is Literature?” A Definiion Based on Prototypes,” Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguisic,(Volume 411), 2 (July, 1997), 3. 3 Ibid, 2. 2 musicans, and so forth)4. Music is so naturally united with us that we cannot be free from it even if we so desired. Music has performed an important stages of a person‟s life with specific types or pieces of music. There are birth songs, birthday songs, holiday songs, retirement songs, and even death songs. Music‟s influence is so prevalen that, to this day, most of us remember songs that played it our most important moments.5 Music„s intimacy is so powerful that it seduces us. -

Wedding Songs

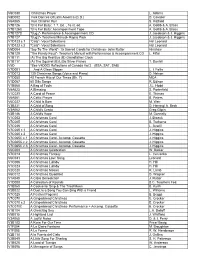

*Ideas for the wedding waltz and subtle backround music WEDDING SONGS & BALLADS ARTIST SONG Aaron Neville/Linda Rondstandt I don’t know much Absent Friends I don’t want to be with nobody but you Aerosmith I.Dont.Want.to.Miss.a.Thing Alex Lloyd Amazing Allison Kraus Just when I needed you the most Andy Williams Hawaian wedding song Annie Lennox No more I love you’s Ashanti Fooloish Ashanti Love again Babybird Your gorgeous Backstreet Boys Incomplete Bad English When i see you smile Barbara Streisand A love like ours Barbara Streisand Queen bee Barbara Streisand The woman in the moon Barbara Streisand What are you doing the rest of your life Ben Lee Gamble everything for love Berlin Take My Breath Away Bette Midler The rose Bette Midler Wind Beneath My Wings Billy Joel Just the way you are Billy Joel She’s always a woman Bon Jovi Always Bon Jovi Bed of Roses Bonnie tyler Total eclipse of the heart Boris gardiner I wanna wake up with you Boyz 2 Men I'll Make Love Boyzone Love me for a reason Brian Adams & Barbara Streisand I've Finally Found Someone Brian Adams Everything I Do (I Do It For You) Brian Mcfadden & Delta Goodrem Almost here Bryan Adams Heaven Bryan Adams How Do You Talk To An Angel Bryan Adams Now and Forever I Will be Your Man Bryan Mcknight Back to one Carly Simon I got to have you Celine Dion & Harry Connick Jr. When I Fall In Love Celine Dion Angel Celine Dion Beauty & the beast Celine Dion Because you loved me Celine Dion It’s all coming back to me now Celine Dion My heart will go on Celine Dion Tell him Celine Dion The